Confirmed by science

« previous post | next post »

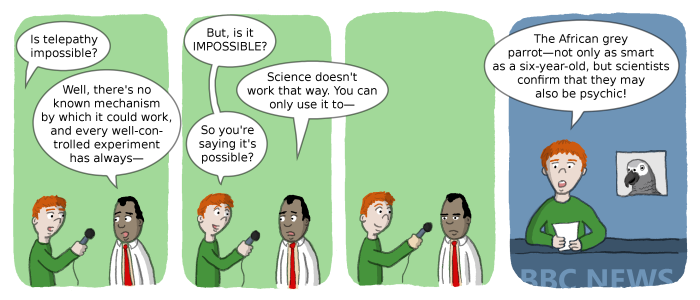

Rudis Muiznieks, a skeptical cartoonist whose work appears at cectic.com, posted this strip on May 30:

The backstory:

"Parrot telepathy at the BBC", 1/28/2004;

"BBC's duplicity stuns Language Loggers", 1/15/2007;

"Invisible telepathic parrots", 6/30/2007.

In the case of the telepathic parrot, I don't think that the BBC's reporter actually bothered to manipulate a scientist into validating the story line. But the wonderful cow-dialect story of 2006 does provide a documented case of this type: see "It's always silly season in the (BBC) science section", 8/26/2006.

I should also point out that the BBC is not uniquely guilty in this respect, and scientists are not uniquely victimized — when a journalist questions a source, it's often not in search of information, but in search of a quote to slot into a predetermined narrative framework. Some examples of this sort are discussed in "Ritual questions, ritual answers", 6/25/2005; and "Down with journalists!", 6/27/2005.

James A. Crippen said,

July 8, 2008 @ 2:39 pm

Has anyone done an analysis of the journalistic narrative frameworks which are used for science journalism? If scientists were made aware of exactly how their quotes and statements are going to be fit into a “news” narrative, then maybe they’d be more careful of exactly how they say things to reporters. If no discourse analyst has looked into this perhaps they should, the task could be considered a service to the scientific community.

One idea I had recently was that the AAAS ought to develop a set of guidelines that the working scientist can follow for describing science to journalists. Not to the public, but specifically for scientist-journalist communication. If scientists were more defensive about how they get quoted, perhaps journalists would be less able to twist their words.

fev said,

July 8, 2008 @ 3:02 pm

Journalistic narratives of science are discussed fairly often in the journal Public Understanding of Science. (Lots of different "science" shows up there, but one good example is Conrad Smith's 1996 article "Reporters, news sources, and scientific intervention: The New Madrid earthquake prediction").

As other authors in that journal have pointed out across the years, journalists may get the byline, but lots of other people participate in the public construction of science — among them university news buros, the public and scientists themselves. I don't mean to excuse the sort of stuff Mark is describing, just to suggest that shooting the messenger would only solve part of the problem.

Mark Liberman said,

July 8, 2008 @ 3:06 pm

For an anecdote and some discussion in support of fev's comment that "lots of other people participate in the public construction of science", let me refer you to "Flacks and hacks and brainscans", 11/23/2007.

Ray Girvan said,

July 8, 2008 @ 7:57 pm

If scientists were more defensive about how they get quoted, perhaps journalists would be less able to twist their words

The issues were summarised quite nicely in When science and journalism collide a while back (an unusually astute critique for the BBC).

"Scientists, operating in a culture which places enormous importance on accuracy and precision, can find reporters' occasional sloppiness infuriating.

Equally, journalists often find scientists unworldly in their insistence on caveats and qualifications at every turn and their use of technical language, when reporters are desperately trying to simplify complex concepts and make them accessible to a general audience."

A lot of the difficulty is that science simply doesn't fit journalism's story-telling formats about science: for instance, "Equally Balanced Controversy" or "Breakthrough discovery X found" or "Breakthrough Cure for Y found". However judicious the quote a scientist makes, it'll be shoe-horned into something within that framework.

Nathan Myers said,

July 8, 2008 @ 10:02 pm

The single quality most common to journalists manifests as laziness. (They would describe it as deadline pressure.) Scientists can take advantage of this laziness by providing ready-made copy for them to cut and paste from. Accuracy can be aided by repeating key facts in more than one paragraph, so that altering one would create an inconsistency their editor might frown upon. To avoid being shoehorned into a reporter's narrative, provide a narrative yourself. (If there's no compelling narrative, there's not really a story, and no reason to involve a journalist.) The narrative needn't involve the scientific subject; it might involve a researcher's spouse, or vindication of one's embattled major professor, or even just an interesting picture whose caption offers a place to shovel a fact or two.

Breakthrough and controversy stories are OK, but people and reporters love an underdog story best. Every true scientist has to be an underdog.

Ray Girvan said,

July 8, 2008 @ 10:33 pm

Every true scientist has to be an underdog

And unfortunately that drives one of the syndromes of press coverage: the inflation of the significance of minority views in science/medicine.

Equally unfortunately, the strategy of ready-made story exists and is much misused because of that same press laziness. The UK press has a constant stream of science non-stories (The perfect formula for wibbleberry soup) and wonder breakthroughs (Wibbleberries 'fight cancer') that always boil down to some unexamined promotional agenda by the Wibbleberry Marketing Council or some scientist who has done preliminary in vitro work and jumped the gun to sell wibbleberry supplements long before anyone's done clinical trials.

David Starner said,

July 8, 2008 @ 10:40 pm

I know my grandfather, once Treasurer of the State of Oklahoma, gave up talking to wjournalists because he felt that every time he tried, he got misquoted.

Max Porter-Elliott said,

July 9, 2008 @ 5:08 pm

I think this holds true for the majority of the journalists today. There was an interesting video on ted.com about how media coverage is distributed. Something like 95+ percent of the new comes from within the US and there are less than 1% of the actual journalists in other countries. Anyone remember the telephone game? And thats what we are forced to watch for news…