Two words for truth?

« previous post | next post »

The "No Word For X" trope is a favorite item in the inventory of pop-culture rhetorical moves — the Irish have no word for "sex", the Germans have no word for "mess", the Japanese have no word for "compliance", the Bulgarians have no word for "integrity", none of the Romance languages have a word for "accountability", and so on …

In today's New York Times, Andrew Rosenthal presents an unusual variant: "Two Words For X". Specifically, he advises us "To Understand Trump, Learn Russian":

The Russian language has two words for truth — a linguistic quirk that seems relevant to our current political climate, especially because of all the disturbing ties between the newly elected president and the Kremlin.

The word for truth in Russian that most Americans know is “pravda” — the truth that seems evident on the surface. It’s subjective and infinitely malleable, which is why the Soviet Communists called their party newspaper “Pravda.” Despots, autocrats and other cynical politicians are adept at manipulating pravda to their own ends.

But the real truth, the underlying, cosmic, unshakable truth of things is called “istina” in Russian. You can fiddle with the pravda all you want, but you can’t change the istina.

My knowledge of Russian is limited to the feeble residue of time with Russophone grandparents when I was 4 or 5 years old, and the even feebler residue of a semester of Russian in college. And Mr. Rosenthal was once Moscow bureau chief for the AP, so presumably he has some facility with the language. But I'm skeptical of facile language/culture connections like this one, and the logic of Rosenthal's connection between Donald Trump's character and the Russian lexicon seems unusually diffuse even by the standards of the punditocracy.

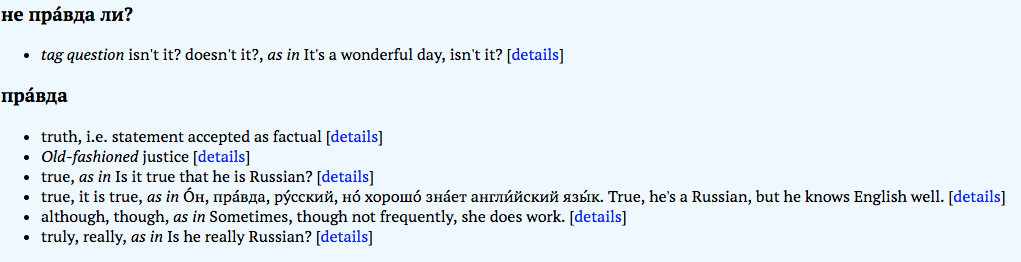

A quick check at the Cornell Russian Dictionary Tree tends to support my skepticism — here's the entry for правда:

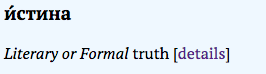

And here's the entry for истина:

This suggests that the real difference is not that правда is subjective and infinitely malleable, while истина is cosmic and unshakable. Rather, правда is ordinary, while истина is hifalutin.

But I invite readers who actually know Russian to explain the difference and evaluate Rosenthal's interpretation.

Update — we have to admit that English has quite a few words for truth: accuracy, correctness, factuality, verity, sooth, … What lessons about our politics, if any, should speakers of other languages draw from this?

Viseguy said,

December 15, 2016 @ 9:29 pm

I'm not a native speaker, I only played one on TV — well, when I was a Russian major, 40+ years ago, I had the lead in a Russian-language college production of Chekhov's The Bank Manager — so take this for what it's worth. I believe that правда properly means truth in the non-malleable sense (but the Communist Party of the Soviet Union undoubtedly spoiled it by appropriating it for the name of its official newspaper, so Rosenthal may be onto something there), while истина, for me, is not only more elevated in register but also has connotations of sincerity or genuineness (but not necessarily cosmically Objective Truth). I'm eager to hear what native speakers have to say.

In the meantime, I can't resist repeating the old Krushchev-era joke about «Правда» ("Truth") and «Известия» ("News"): В «Правде» нет исвестий, в «Исвестии» нет правды. ("Pravda has no news, Isvestia has no truth.)

Viseguy said,

December 15, 2016 @ 9:38 pm

Make that: В «Правде» нет известий, в «Известии» нет правды.

Moroz said,

December 15, 2016 @ 10:38 pm

"The word for truth in Russian that most Americans know is “pravda” — the truth that seems evident on the surface. It’s subjective and infinitely malleable, which is why the Soviet Communists called their party newspaper “Pravda.”

He's got it the wrong way around. For some non-russians "pravda" might mean what he described BECAUSE of the communist "Pravda" newspaper that was untruthfull. I think that's where it's at. I'm pretty sure "pravda" just means "truth" for Russians in daily conversation.

(Polish native speaker who's studying Russian)

Bozo said,

December 15, 2016 @ 10:49 pm

A native Russian speaker here:

Pravda indeed feels like a more commonn, usual word to express something that is true. It seems to have common etymology with words like "pravilny" (correct) or "pravy" (right). Russians sometimes use the word pravda with the question mark where Americans will ask "Really?" Or "Is that so?"

Istina is indeed perceived as the deeper truth. It seems to have derived from the same place as the verbal "is" in English (and ist/est etc). Istina is then simply something that is, that exists.

I would add that biblically/religiously mostly istina is used where the English says "truth". I.e. "I am the way, the truth and the life", "you shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free" etc. The standard transtion of the Latin "in vino veritas" also uses istina in Russian. There is also an expression "istina v posledney instantsii" — something like the final authority, that can confirm the deepest and most ultimate truth.

This said, I think the nyt article is pompously and unnecessary complicated. The difference in the usage of the two Russian words as applied to the US presidential election exists only in the author's interpretation. He could have just as successfully argued by saying, wholly in English, "on the one hand,… (blah blah, Trump's supporters are not racists, since he disavowed them), on the other hand (blah blah, he attracted many of them). The introduction of the Russian lexical distinctions would then be unnecessary, and his argument would gain or lose nothing from such an omission.

It could also be said, with somewhat less dubious linguistic appeal to the Russian language, that the pravda is that Clinton was probably the better candidate and won the popular vote, but the istina is that she lost because of her own arrogance and incompetence and because more people voted for Trump in the states that mattered.

John Roth said,

December 15, 2016 @ 10:57 pm

Is Hat around anywhere?

Chris C. said,

December 15, 2016 @ 11:12 pm

I wonder if the distinction isn't due to istina being a more ecclesiastical word for "true", as it's essentially the same as in CS? "Pravda" also occurs in CS, but with the sense of "righteousness" or "justice".

Chas Belov said,

December 16, 2016 @ 1:21 am

@John: Hat as in xkcd or as in Language Hat?

Tom S. Fox said,

December 16, 2016 @ 2:22 am

Could we stop calling any feature that English doesn’t share with other languages a “linguistic quirk”?

Sergey said,

December 16, 2016 @ 2:36 am

I'd say that there is something to it but not exactly what the article says. To start with, the word "pravda" actually has two meanings: (1) the truth in the context as opposed to a lie, and (2) the vision of the world from the standpoint of a certain group of people. The newspaper "Pravda" actually started with the second meaning, it was named "Рабочая правда" ("Workers' truth"), with the later branching into "Солдатская правда" ("Soldiers' truth") and so on. And only later, after the communists had killed all the opponents, it was consolidated and renamed just "Pravda", creating the implication of the first meaning.

"Istina" is a more scholarly word that mostly matches the first meaning of "pravda". But I would match it more to the English phrase "ground truth": i.e. something that had been truly observed and confirmed as opposed to the speculations. Overall I'd say that the shade of meaning of "pravda" is more subjective, something that is true from the viewpoint of one observer while "istina" is more objective and agreed upon by multiple observers. But in practice these words can be used interchangeably, although again "istina" is a more scholarly word that would be used more in the scientific or court papers while "pravda" would be used in the common speech.

Reinhold {Rey} Aman said,

December 16, 2016 @ 2:39 am

@ Bozo:

Russians sometimes use the word pravda with the question mark where Americans will ask "Really?" Or "Is that so?"

Similarly in Spanish: ¿Verdad? ("Truth?") and in German: Nicht wahr? ("Not true?")"

Sergey said,

December 16, 2016 @ 2:41 am

To follow up: I've read all the comments, and I'd agree that the good (but not 100% coinciding) English translation of the second meaning of "pravda" is "justice".

Sergey said,

December 16, 2016 @ 2:53 am

Another thought: the twist of the name "Pravda" is not unique to the Russian communists. The same can be observed in America. The socialist group that names themselves "liberals" happens to be against liberties, for maximum regulation. And not just for regulation but for the regulation of the religious type, positioning themselves essentially as a religion, in the same sense that communism was the state religion in the USSR. The socialist group that calls themselves "progressive" is actually for the social regress, advocating the return to a version of the new and improved feudalism, just as in the Marxist "dialectic spiral development". The name "conservatives" is misleading too, actually labeling the group that is generally advocating the liberty and social progress.

Anna M. said,

December 16, 2016 @ 4:20 am

Native speaker of Russian here. Agree with Sergey's first comment about the semantic distinction between pravda and istina, and with the first half of Bozo's comment.

However, I feel compelled to point out that nothing of what Rosenthal calls "istina" in the article ("…that Trump’s base was heavily dependent on racists and xenophobes, [that] Trump basked in and stoked their anger and hatred, and [that] all those who voted for him cast a ballot for a man they knew to be a racist, sexist xenophobe. That was an act of racism.") would actually be called "istina" in Russian. These are also subjective statements, and whether I agree with them or not is irrelevant — they are not "istina". Istina is reserved for fundamental truths (viz., Earth is round). To label a statement such as "That was an act of racism" istina is an act of propaganda. What a bummer, for the title and subtitle of the article were so provocatively delicious!

[And now we come to the most depressing part of my post. At this point, I feel obliged to explain that I (a naturalized American citizen) did not vote for Trump and am devastated by his election. I am sad to have to say this not because it's not true, but because it is actually irrelevant to my point (that the Rosenthal article, and to a lesser extent the last sentence of Bozo's comment, are both mislabeling istina); yet I feel that I must make that disclaimer or else my comment will not be take seriously here. [Should I turn the screw further to add the entirely subjective comment that this — my sense that what I say on a semantic matter will not be taken seriously without some anti-Trump bona fides — is why Trump won?]]

Ozaru said,

December 16, 2016 @ 5:11 am

In an unashamedly unscientific study (especially given Google's recent failure to observe its 'exact' operators, q.v. https://twitter.com/ozaru/status/808994811395063808), I went to https://www.google.co.jp/search?q=%22%D0%B8%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%B0%22%7C%22%D0%BF%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%B4%D0%B0%22%20%22post-truth%22 to see what the Russians use for the 'word of the year', post-truth (q.v. https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/word-of-the-year/word-of-the-year-2016).

What I see from the first few hits is:

Как слово post-truth, названное «словом года», повлияет на нашу жизнь. … Истина объективна, а правда субъективна.

«post-truth» … truth («истина») … правда

«Post-truth» … «постправдивый» … «post-truth» … «truth» (правда)

post-truth … правда

post-truth … Правда

"Пост-правда" ("Post-truth")

пост-правда пост-истина (инг. post-truth)

Политика постправды (англ. post-truth politics)

post-truth … истина

"постправда" (post-truth) … истина

The objective/subjective distinction made me think of the numerous Japanese words for truth/fact/reality etc.: 真実, 真理, まこと(誠・真など), 本当, 事実, 現実… Post-truth seems to be rendered most commonly as ポスト真実 or 脱真実. Discussions of the different nuances are common (e.g. http://detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp/qa/question_detail/q1030427405) but often seem to get bogged down in quasi-self-referential dictionary-style analysis of the constituent characters (along the lines "reality means 'that what is real'" – yeah, thanks guys, really helpful). But perhaps there is a general feeling that 真実 is 'consistently true facts' while 真理 is rather 'universal principles', and 本当 is simply 'true' in the widest sense possible.

I did try to see how Japanese/Russian speakers translated these words, but as shown at http://krakozyabr.ru/2012/05/pravda-%E7%9C%9F%E7%90%86-%E7%9C%9F%E5%AE%9F-%E7%9C%9F/ or https://ja.glosbe.com/ru/ja/%D0%B8%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%B0 it seems the concepts are really too nebulous to define through narrow definitions. In the end it does come down to words meaning just what we choose them to mean, as Carroll wrote.

A final note: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Truth says, "any translation of the word apparently fails to accurately capture its full meaning (this is a problem with many abstract words …). Thus, some words add an additional parameter to the construction of an accurate truth predicate. Among the philosophers who grappled with this problem is Alfred Tarski, whose semantic theory is … that truth cannot be consistently defined"

maidhc said,

December 16, 2016 @ 5:35 am

I'm reminded of a SNL sketch from the 1970s featuring Paul Harvey (loud-mouthed radio commentator at the time), when he decided the Soviet press was more honest than the American press and started shouting "Da! Es pravda!".

I'd kind of like to revive "the Irish have no word for 'sex'" discussion because what it really was about was "the Irish have no word for 'fuck'", which was a point that pretty much everyone missed at the time. Because it was based on a radio interview, the interviewee was not able to say "fuck" over the air. Irish does have a word for "sex". But does it have a word for "fuck"? The examples provided were not words but phrases ("ag buaileadh craiceann"=bumping skin).

That's a question that I think has not been addressed on this forum. It is complicated by the fact that Irish has adopted English swear words. So in modern Irish you could say "Tá muid fucailte" ("We're fucked"). But is there a more Gaelic way to express it?

January First-of-May said,

December 16, 2016 @ 6:03 am

The phrase is, of course, В «Правде» нет известий, в «Известиях» нет правды (note the plural form of the second name, and compare the plural form of English "news" – though Russian for "news" would normally be новости).

As another native Russian speaker, I basically agree that the base situation is "правда is ordinary, while истина is hifalutin", though the stylistic difference does result in some meaning shift (Bozo's description of the difference is accurate enough to be правда, though probably not quite precise enough to be истина).

Pravdivaya istina said,

December 16, 2016 @ 6:17 am

Another native speaker here. The difference between pravda and istina that Rosenthal is refering to does exist in some contexts where pravda is explicitly used as an antonym of istina. «У неё своя правда», lit. “she has her own truth”. You can't really say «У неё своя истина»*, on the opposite, there's a saying «правда у каждого своя, но истина одна», lit. “everyone has their own pravda, but there's just one istina”.

* if you google “своя истина” you will mostly get religious websites that are trying to prove that their believes are istina (not pravda) :-)

AntC said,

December 16, 2016 @ 6:21 am

@maidhc But does [Irish] have a word for "fuck"?

Despite (rather ingenuous) protestations to the contrary, "feck" seems to serve the purpose.

Simon P said,

December 16, 2016 @ 7:00 am

So it's like "true" vs. "the truth"?

John Roth said,

December 16, 2016 @ 9:09 am

@Chas

I was looking for Language Hat, of course. However, here's a lengthy explanation of the difference between pravda and istina, using Anne Wierzbicka's cultural scripts formalism:

https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/347547/wierzbicka-russian-cultural-scripts.pdf

This may be a good deal more than anyone wants to know.

Michael Cargal said,

December 16, 2016 @ 9:15 am

It is a fact that English has no word for eating strawberries. Therefore Americans do not know that strawberries can be eaten.

languagehat said,

December 16, 2016 @ 9:24 am

I was looking for Language Hat, of course.

Here I am. I agree with (and defer to) the native speakers who have already commented; I was going to add the saying «правда у каждого своя, но истина одна», but Pravdivaya istina got there first. Great discussion!

ajay said,

December 16, 2016 @ 9:45 am

Americans do not know that strawberries can be eaten.

When it is eaten, it ceases to be a strawberry. Therefore Americans are correct in thinking that there is no such thing as an eaten strawberry, any more than there is such a thing as a melted ice cube.

Robert Coren said,

December 16, 2016 @ 10:54 am

@Reinhold {Rey} Aman: German nicht wahr? is more like the confirming "Isn't it/aren't we/", etc., or more simply the equivalent of the French n'est-ce pas? I think the German equivalent of a skeptical "really?" would be wahrlich? or wirklich?

FM said,

December 16, 2016 @ 12:13 pm

When (spurred by @Ozaru) I first thought about "post-truth" in Russian, "post-правда" and "post-истина" both sounded awkward. After reading the Wierzbicka piece, I see why: "post-truth" relies on a notion of truth achievable by logic and reason, which is suddenly inaccessible. But that's neither правда nor истина: the former is, first and foremost, true to the heart of the person telling it, whereas the latter is cosmic and exists without anyone necessarily knowing it. When the process of and confidence in achieving истина or the social cachet and acceptance of the existence of истина breaks down, истина itself cannot be counted as a casualty.

That said, Wierzbicka's work has a certain truthiness to it that I find irresistible but that my forebrain wants to put giant flashing warning lights on.

D.O. said,

December 16, 2016 @ 1:49 pm

Pravdivaya istina is surprising, but istinnaja pravda is used for intensity, something like real truth.

To Understand Trump, Learn Russian

Among idiotic reasons to learn Russian this must be among the frontrunners.

У неё своя истина

истина в вине

Reinhold {Rey} Aman said,

December 16, 2016 @ 2:01 pm

@ Robert Coren:

@Reinhold {Rey} Aman: German nicht wahr? is more like the confirming "Isn't it/aren't we/", etc., or more simply the equivalent of the French n'est-ce pas? I think the German equivalent of a skeptical "really?" would be wahrlich? or wirklich?

Wirklich? ("Really?", "Indeed?") is standard. Wahrlich? ("Truly?"), however, is a higher register and rarely used in everyday language. It's "biblical, quot; like verily.

As to Nicht wahr ("Not true") meaning "Really?", I should have used an exclamation point, not a question mark:

A: "Heute bin ich 80 Jahre alt." (Today I'm 80 years old.)

B: "Nicht wahr!" (That can't be true!)

Ellen Kozisek said,

December 16, 2016 @ 10:15 pm

The socialist group that names themselves "liberals" happens to be against liberties, for maximum regulation.

I'm not sure who you mean by that, but the people I know to be called liberals certainly aren't against liberties. But that's also irrelevant to the point, since they are called liberals, not libertarians.

Bastian said,

December 17, 2016 @ 4:14 am

@Reinhold @Robert The same holds for Spanish verdad.

Spectator said,

December 17, 2016 @ 5:01 am

It looks like the distinction between "true" and "right".

Robert Coren said,

December 17, 2016 @ 11:07 am

A: "Heute bin ich 80 Jahre alt." (Today I'm 80 years old.)

B: "Nicht wahr!" (That can't be true!)

Ah, so it's more like modern colloquial "No way!"

anglogermantranslations said,

December 18, 2016 @ 10:57 am

@Robert Coren @Reinhold

Wahrlich is biblical usage ("Verily, verily I say unto you" = Wahrlich, wahrlich, ich sage euch).

Wirklich is also quite old-fashioned. More common usage is "Echt?" these days. Using wirklich or ehrlich or tatsächlich dates you. (I use them, I never say echt.)

Robert Coren said,

December 18, 2016 @ 11:08 am

Well, my German is very dated. I studied it in college 50 years ago, but most of my contact with it since then has been through Lieder and opera, so we're talking both archaic and poetic.

Marja Erwin said,

December 18, 2016 @ 2:26 pm

"The name "conservatives" is misleading too, actually labeling the group that is generally advocating the liberty and social progress."

Are you frakking kidding me?

Movement conservatives here in America are defending white supremacism, cis and het supremacism, male supremacism, ableism, xenophobia, and the destruction of the environment we depend on.

They are attacking people's rights, and that's not advocating liberty, or advocating social progress towards a better world, though that may be advocating progress towards a worse one.

Movement conservatives, with the help of the electoral college, are about to elect a candidate who boasted about his sexual assaults.

Movement conservatives are passing laws to try to out trans people and expose us to violence. See Hate Bill 2. Movement conservatives are blocking policies that would keep public [government] schools from singling out trans students and exposing them to more bullying. Some are saying we're in league with Satan. Some are trying to pass laws establishing hostility for us as a specially-privileged religious belief.

It's an accursedly scary situation.

Thomas Lumley said,

December 19, 2016 @ 12:43 am

The (apparently false) idea that 'правда' has been corrupted to just mean 'official truth' in informal modern Russian isn't a new one — I've seen it several times in US-written fiction. I think Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle have used it.

BZ said,

December 19, 2016 @ 1:07 pm

Since we're talking about Soviet newspapers and "Izvestia" has already been mentioned, I should point out that there are also two Russian words for "news", the most common one is "novosti" (which like the English word comes from the same word as "new", "noviy"). "Izvestia", on the other hand, etymologically comes from something like "that which one was informed about". It is much more rarely used. Although there is a substantial overlap, it retains some of its etymological quirks. If someone asks you what "izvestia" you have, they don't want news about you or even from you. They want something you acquired in some way, usually about a specific topic. For these reasons, it always seemed strange to me that a newspaper was named "Izvestia" and not "Novosti". On the other hand "posledniye izvestia" for "latest news" is a set idiom, and is often what TV News are referred to in Russia (Novosti is also common. Posledniye novosti seems redundant, though it wouldn't be in English). Then again, I wouldn't call a newspaper "truth" in any language either.