Ask Language Log: "Something deeply strange…"

« previous post | next post »

Sometimes two fairly ordinary things combine to create something bizarre. Karen Davis writes:

It seems to me that there is something deeply strange in this quote, from a 1922 novel by Joseph S. Fletcher called The Middle of Things:

"Robbery wasn't the motive. Murder was the thing in view! And why? It may have been revenge. It may have been that Ashton had to be got out of the way. And I shouldn't wonder a bit if that wasn't at the bottom of it, which is at the top and bottom of pretty nearly everything!"

"And that, ma'am?" asked Mr. Pawle, who evidently admired Miss Penkridge's shrewd observations, "that is what, now?"

"Money!"

Karen's analysis of the deep strangeness:

Specifically, it's the use of that. The first time I read the clause "if that wasn't at the bottom of it" I thought "that" was referring to "getting Ashton out of the way", and I couldn't figure out how getting him out of the way was "at the top and bottom of pretty nearly everything."

But Miss Penkridge is using that to refer to something that hasn't been said yet – and then the referent is another pronoun (which). This sort of splitting of the "that which" reads very oddly to me. It's as if she's dropping out a noun phrase and just keeping the two relatives ("the thing that was at the bottom of it which is the thing at the top and bottom…").

There's some other evidence in this same novel that Mr. Fletcher is friendly to relative clauses starting with "that which":

"It seems to me most remarkable that such as that which you suggest should ever enter your head, sir." [p. 204]

… and Viner, looking right and left, saw that the small streets running off that which he was traversing were still more dismal, still more shabby. [p. 256]

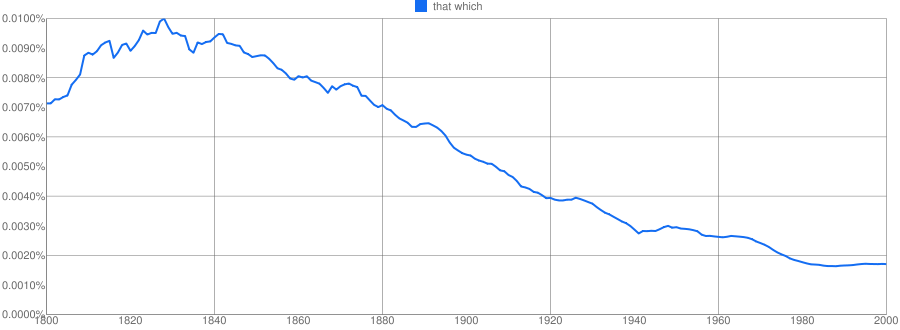

This construction has been in decline since about 1840:

But "… that which …", though a bit highfalutin, is far from unknown even today. There are plenty of recent books featuring it, starting with Pope Benedict's Seek That Which Is Above, and descending through That Which Awakens Me ("A Creative Woman's Poetic Memoir of Self-Discovery") to That Which Bites ("Young Julia Poe … celebrates her 22nd birthday as a cattle rustler, fighting the vampire factions alongside a gun-toting nun with an even bigger vendetta").

There is also some evidence from The Middle of Things that Fletcher doesn't mind extraposing relative clauses from time to time:

Two episodes occurred during the comparatively brief proceedings which made him certain that all was not being brought out. [p. 44]

Placing a relative clause at the end of the clause containing its head, separated from the head by various post-verbal elements and perhaps the main verb itself, is uncommon but perfectly normal. It most often happens when the head (or antecedent, if you prefer) is the subject of the sentence, as in these web examples:

If a man came in who did not belong to the association but would be willing to join, would there be any objection to his joining?

The coyote hasn't been built who can outyap Hank the Cowdog.

The water supply hasn't been made that can put out a manure fire.

The dictionary hasn't been written which could supply words to describe it.

… the drayman was dead who delivered the beer in question, but his handwriting was proved ; and this was held good evidence of the delivery.

You must have given me the wrong phone number because our secretary said the woman was dead who had had that number when she called it.

The same summer King Olav learned that the ship was lost which he had sent to the Faroes for scot the summer before, and it had not come to land anywhere, such as had been heard of.

Neither …that which… nor relative-clause extraposition is problematic on its own — but put them together and you can have a cognitive train wreck, for the kinds of reasons that Karen gives:

The sentence isn't by any means impossible to parse, though I couldn't without the clue provided by Mr. Pawle's follow-up question (that is what?) – but I don't think I've encountered [such a structure] before, certainly not very often. (It's not helped by the misplaced comma before which, either; surely that's a restrictive relative clause, defining which "that" she means.)

If Karen continues reading the novels of Joseph Smith Fletcher, she'll find some other examples, for instance this sentence from Dead Men's Money:

There was, I say, nothing visible on all that level of scarcely stirred water but our own sails, set to catch whatever breeze there was, when that happened which not only brought me to the very gates of death, but, in the mere doing of it, gave me the greatest horror of any that I have ever known.

But this instance is not so likely to send readers down an anaphoric garden path, even without the priming contributed by the earlier discussion.

Ian Preston said,

January 20, 2011 @ 6:36 am

But "… that which …", though a bit highfalutin, is far from unknown even today.

It's far from unknown even for it to be discussed on Language Log.

Sid Smith said,

January 20, 2011 @ 6:43 am

Talking of garden paths (sorta), the front page of the NYT's web page contains the following headline, deeply disturbing to all fans of a certain television Time Lord:

Doctor Who / Performed / Abortions Is / Charged With / Murder

David Eddyshaw said,

January 20, 2011 @ 6:47 am

It's not so highfalutin if you read it with emphasis on the "that"; perhaps Fletcher had that in his mind and accordingly didn't notice the awkwardness of the printed version.

[(myl) Stressing that in the original example helps clarify that it's not meant anaphorically, but it surely doesn't change the fact that "that which" (with or without extraposition of the relative clause) is an antique construction that today (and even in 1922) is only used by those reaching for a rather elevated style — as you can tell by looking at the books with "that which" in their titles.]

Dhananjay said,

January 20, 2011 @ 8:02 am

"That […] which" where the 'that' is merely proleptic is for me a feature of translationese, that unlovely register which faithfully reproduces as much of the syntax of the source language as possible and is common, especially at the lower levels, in classrooms of Latin, Greek, and, no doubt, other ancient languages. The result, one might say, is not really or fully translation, but a kind of description of the original meant only to demonstrate one's understanding of it. But a nice example of an overuse of the construction to achieve a high style is in the frequent translation of that Nietzschean motto "Was mich nicht umbringt, macht mich stärker" as "That which does not kill me…" rather than the plainer and more faithful "What doesn't kill me…"

John Lawler said,

January 20, 2011 @ 9:58 am

… and nobody's even mentioned the hypernegation that brackets and further clouds the relative pronoun:

I shouldn't wonder a bit if that wasn't at the bottom of it.

Eric P Smith said,

January 20, 2011 @ 10:49 am

John Lawler: but I was on the point of doing so before I read your comment. Fowler describes "I shouldn't wonder if … not …" as a 'sturdy indefensible'.

TonyK said,

January 20, 2011 @ 11:25 am

This reminded me so much of my little boy (who is bilingual English-Hungarian) that I looked up Joseph S. Fletcher to see if it wasn't perhaps the pen name of (say) Nyílász József. It turns out he was 100% British. But the syntax is pure Hungarian!

Mr Punch said,

January 20, 2011 @ 12:14 pm

I agree with David – it reads badly, but could be plausible speech. Incidentally, J.S. Fletcher's "The Middle Temple Murder" was supposedly Woodrow Wilson's favorite mystery.

Ray Dillinger said,

January 20, 2011 @ 12:58 pm

I wouldn't find anything "strange" in any of these passages. They could certainly be tightened up if writing for brevity and clarity, but Fletcher was not. He was writing narration as told by a protagonist. To me these passages seem to be fine examples of the rhythms and idioms of entirely plausible protagonists of that period..

The Ridger said,

January 20, 2011 @ 1:14 pm

Actually, none of Fletcher's books that I've read so far (Karen here, by the way) are told "by a protagonist". Instead, they're told by an omniscient author – he generally sticks to limited third person but has a habit of dropping in sudden insights from someone else, as this in a book basically told from Spargo's POV (The Middle Temple Murder, which I'm reading right now):

Jessie Aylmore took a sudden liking to Spargo because of the unconventionality and brusqueness of his manners.

But at any rate, while most of the time I don't have a problem with his syntax, the passage that sparked this was entirely opaque to me until I'd read two more sentences. That may have been normal usage – or at least normal for an old lady – of the time, but I definitely find it odd, to say the least. An unsplit "that-which" (And I shouldn't wonder a bit if that which is at the top and bottom of pretty nearly everything wasn't at the bottom of it!") wouldn't be, though.

Twitter Trackbacks for Language Log » Ask Language Log: “Something deeply strange…” [upenn.edu] on Topsy.com said,

January 20, 2011 @ 2:54 pm

[…] Language Log » Ask Language Log: “Something deeply strange…” languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=2912 – view page – cached Sometimes two fairly ordinary things combine to create something bizarre. Karen Davis writes: […]

MJ said,

January 20, 2011 @ 9:30 pm

@The Ridger Which makes me wonder why Fletcher split it, and not only split it but inserted a comma before the "which." That makes me want to read the clause nonrestrictively rather than restrictively. I think that could work if _that_ were emphasized. I know it isn't italicized in the text, but maybe it should have been:

The Ridger said,

January 21, 2011 @ 5:38 am

I'm sure he split it to get the "at the bottom of everything" at the end of the sentence. Which is why I would have gone for a pseudo-cleft (what's at the bottom of it isn't what's at the top and bottom of everything) myself.

But for all I know, elderly British ladies of the upper middle class did speak that way in 1922…

Ask Language Log: “Something deeply strange?” | tonycreary said,

January 23, 2011 @ 7:20 pm

[…] Source: http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=2912 […]