Phys-splaining

« previous post | next post »

Ray Norris, "Why old theories on Indigenous counting just won’t go away", The Conversation 9/5/2016:

Last year researchers Kevin Zhou and Claire Bowern, from Yale University, argued in a paper that Aboriginal number systems vary, and could extend beyond ten, but still didn’t extend past 20, in conflict with the evidence I’ve mentioned above.

As a physicist, I am fascinated by the fact that the authors of this paper didn’t engage with the contrary evidence. They simply didn’t mention it. Why?

Although my training is in astrophysics, I have for the last few years studied Aboriginal Astronomy, on the boundary between the physical sciences and the humanities, and I am beginning to understand a major difference in approach between the sciences and the humanities.

There was some conversation about this article on Claire Bowern's FaceBook page, including these comments:

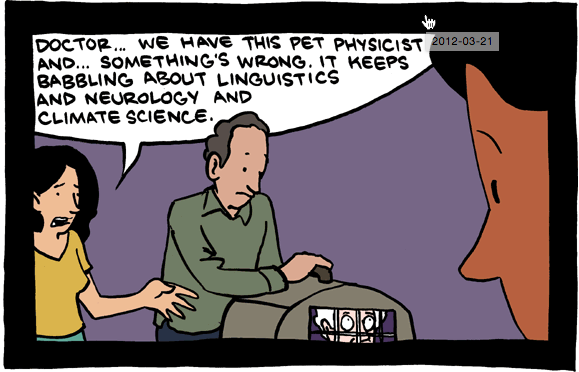

There needs to be a special term for when a physicist "explains" something

Physisplaining, I would say. Ack, this is bad. So you publish a peer-reviewed article on something, and he writes something more like a blog post saying how his kind of science is the only real kind of science, and all those wishy-washy things that call themselves science don't bother looking at the data. "In humanities, the data is often much more dependent on the skills and interpretation of the researcher." Sure.

There's a doubly special kind of physicsmansplaining that talks about disputing your point with data but doesn't present any data.

"I have a vaguely remembered anecdote that thoroughly refutes you foolish humanities types"

Phys-splaining. Keeps the monosyllabic prosody of the model.

But the best comment, in my opinion, was the link to an old SMBC strip from 3/21/2012, which we noted back when it appeared:

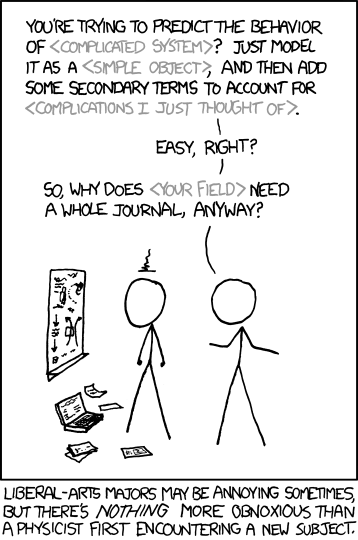

We've had occasion from time to time to comment on similar episodes, e.g. "Word string frequency distributions", 2/3/2013 — though that example involved dubious interpretations of large bodies of undigested data, rather than arrogant inference from half-remembered anecdotes, and therefore would be more appropriately critiqued by this xkcd strip, also noted in a comment on Claire's FaceBook post:

Mouseover title: "If you need some help with the math, let me know, but that should be enough to get you started! Huh? No, I don't need to read your thesis, I can imagine roughly what it says."

Oskar Sigvardsson said,

September 6, 2016 @ 7:36 am

Linguists aren't innocent in this either, this is roughly representative of my response to hearing Noam Chomsky discuss "common sense" political philosophy, despite being roughly on the same side of the political spectrum.

[(myl) I agree that there are no innocents — but Noam Chomksy is hardly "linguists" — and he's been making sweeping statements about the inadequacy of other fields since the 1950s, when he was relatively young.]

Michael said,

September 6, 2016 @ 7:58 am

I'm afraid this is a common ailment of aging profs. Burnout is followed by entering fields they know nothing about, making political statements, and offering new methods of teaching their subject. A bit pathetic…

Jonathan said,

September 6, 2016 @ 8:01 am

Economists are the physicists of the social scientists, as much as it pains me to admit it…. which, to be honest, isn't all that often.

leoboiko said,

September 6, 2016 @ 8:09 am

@Oskar Sigvardsson: re: Chomsky:

this even applies intra-linguistically:

leoboiko said,

September 6, 2016 @ 8:17 am

My Facebook says that Ligamen petitum fractum vel pagina deleta sit (in other news, I love the Latin option in Facebook). Has someone bothered responding to Norris yet?

KeithB said,

September 6, 2016 @ 8:29 am

Was Feynman an exception or just another example with his work on Mayan numbers?

Tom S. Fox said,

September 6, 2016 @ 8:34 am

An explanation why Ray Norris is wrong would have been nice.

[(myl) You could start here: Zhou, K. and Bowern, C., 2015, September. Quantifying uncertainty in the phylogenetics of Australian numeral systems. In Proc. R. Soc. B (Vol. 282, No. 1815, p. 20151278). The Royal Society.

Take a look at the data and analysis presented there, and in that context, evaluate Norris's bloviations about how "In physics, data rule supreme" and his completely irrelevant claim that "Ethnographic experiments are not repeatable". His "data" is a couple of touristical anecdotes, and his argument is essentially the same as that of a climate-change denier who hold up a snowball as evidence that global warming is a hoax. ]

Jonathan Badger said,

September 6, 2016 @ 9:00 am

@KeithB

I know psychologists who are still really angry with the way Feynman described experimental psychology (as lacking in rigor and unconcerned with replication) in his famous "Cargo Cult Science" essay.

M.N. said,

September 6, 2016 @ 9:31 am

Norris's article might make sense if there were some linguistic theory that depended on there being no Aboriginal Australian language with number-words past 20. But I can't think of a theory that would actually have that property.

Leslie said,

September 6, 2016 @ 10:38 am

Economists really are the physicists of the social sciences: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2820889

Bloix said,

September 6, 2016 @ 10:54 am

Putting aside his "physicists are smarter than everyone else" nonsense – my father, who was an electrochemist, thought that physicists were annoying busybodies – and the offensive accusations of racism, a significant part of Norris's argument is "the fact that a language doesn't have a word for something doesn't imply that it's speakers don't have the concept of that thing."

Just as, in English, we have no word for light blue that would correspond to pink ( = light red). That doesn't mean we don't distinguish between light and dark blue.

So what is the linguist position? That there's no word for any number higher than three or five, but (as Norris claims) speakers of at least some aboriginal languages easily express higher numbers like "two fives and one" or "three fives of five"?

Do they admit this, but say that it is the result of contact with employers, teachers, and missionaries?

Or do they deny that the combination number system even exists?

Zeppelin said,

September 6, 2016 @ 11:28 am

Re: Chomsky, to me he seems to suffer from Physics Envy. Hence his attempts at universal, formal, logically derived rules for language structure (desperately premature and untestable, given our limited understanding of the human brain and mind and the quality of our linguistic data).

He's tried very hard to distance his linguistic theories from the accusation of "stamp collecting", and believing that he has succeeded, he now feels qualified to phys-splain to people in other fields.

Nathalie said,

September 6, 2016 @ 12:32 pm

These comics are pure genius!

@Jonathan Badger:

I am one of those psychologists, though ironically Feynman's comments on this field were part of the reason I chose to study it…

Bloix said,

September 6, 2016 @ 12:54 pm

But the usual problem with physicists is they say, I don't need your jumble of so-called facts from your pathetic little laboratory, I have a theory that explains everything. Norris is saying something different: "don't tell me there are no black swans, I've seen some," which is conclusive if verified, regardless of how many reams of "no observations of black swans!" data you may have collected. So either you can explain that what the guy has seen isn't a swan, or you admit that there are some black swans.

Y said,

September 6, 2016 @ 1:10 pm

Chomsky, to me he seems to suffer from Physics Envy

Introspective linguistics as a key to hidden Universal Grammar was particle physics envy. Binary features are Computer Science Envy.

Y said,

September 6, 2016 @ 1:52 pm

Now that I've had a look at Zhou and Bowern's paper and at Norris's commentary, I feel annoyance not just at the phys-splaining ("Physicists have a monopoly on logical thinking") but at "gotcha" reading from the sidelines. This is when someone new to a field think they've found a critical fault at a work done by an expert, and find it necessary to crow about it. Here it is about the single sentence by Zhou and Bowern, saying that the Australian Aboriginal Languages in their sample have an upper limit of 20 to their numeral inventories.

Suppose I was a physicist, and suppose I found a flaw in a paper on comparative Pama-Nyungan Linguistics, which is co-written by someone who's worked for years with actual speakers of Australian languages, and who spent many years compiling comparative data from every published and archival source for Pama-Nyungan languages; if I where that physicist, I would write a letter to said co-author, along the lines of "Dear Prof. —, isn't language X, where numerals go up to 28 (see ref. Y), an exception to your statement about the upper bound of 20?" I would be likely to receive a reply explaining the discrepancy, or thanking me for pointing out this incidental error (which does not affect the paper's conclusions). But Norris goes straight to insulting the authors, and everyone else lower in the science pyramid than its Physics Apex.

The same "gotcha, missed a spot" was (and is) a favorite of armchair climate change deniers, who would claim some fatal flaw (urban heat islands, for example) in the painstaking work of thousands of climate scientists, and did not have the humility to to entertain the thought that perhaps they don't understand everything.

Brett said,

September 6, 2016 @ 2:03 pm

@Bloix: "Azure."

rpsms said,

September 6, 2016 @ 2:34 pm

I am troubled by Norris when he ignores the fact that Blake was referring to a quinary system (base-5), where the fact that such a system has no numeral for 5 is trivially true.

The word "ten" is not part of the decimal numeral system either.

ohwilleke said,

September 6, 2016 @ 2:34 pm

"As a physicist, I am fascinated by the fact that the authors of this paper didn’t engage with the contrary evidence. They simply didn’t mention it."

This is pretty much standard practice in my profession (I'm a lawyer) when you don't have any really good rebuttal arguments. Amazingly, it often works.

Mark F. said,

September 6, 2016 @ 2:46 pm

This may sort of repeat Bloix's comment, but has there been work on how languages of this sort are used in counting? Surely there has, right? I never really thought about how a language might have no number words past, say five or ten, but how people might still have routinized ways to count much higher. Is that in fact what happens?

KeithB said,

September 6, 2016 @ 4:08 pm

rpsms:

However, 8 was an octal digit in the first edition of K&R C.

M.N. said,

September 6, 2016 @ 5:13 pm

@ohwilleke: There's nothing to rebut! Non-restricted number systems just aren't relevant to a study of the properties of restricted number systems, which is what that paper is. (See below.)

@Bloix: Read the Zhou and Bowern paper (MYL gave a working, non-embargo link to it in Tom Fox's comment). They talk all about how "compositional" terms for '3' and '4' ('2+1', '2+2') can arise from combinations of other terms in a cyclical manner, and about how the strategies for expressing '3' and '4' in any given language are linked to each other.

Also, check out these slides from the 2011 LSA (Bowern again, with first author Jason Zentz): https://campuspress.yale.edu/clairebowern/files/2015/09/LSA2011numeralsSLIDES-1kaowjr.pdf

They lay out in more detail some of the ways that a "small" number system can use combinations of numerals to express higher numerals (some languages go 1, 2, 2+1, 2+2, 2+2+1, etc, others go 1, 2, 3, 2+2, 2+2+1…). Also, they report that some languages allow "vague" readings of numerals (like the word for '3' also meaning 'a few' more generally), while others don't. That's pretty cool.

They use Bowern's Pama-Nyungan database of 121 varieties, of which "no systems in the survey extend above 20". Same as the paper currently under discussion, perhaps?

Anyway, the black-swannification of this would be people working in a region where black swans are vanishingly rare, in contrast to other regions where all the swans are black. A good theory of swans should be able to explain both black and white swans; therefore, these people study white swans in detail. If they come across a black swan, that's cool, and some future researchers may want to study this black swan and compare it with black swans in other places. But these researchers are focused on white swans; contemporary Swan Theory is pretty good at accounting for black swans (because its pioneers only knew about black swans), but how swan researchers should amend the theory to cover both black and white swans isn't clear, and that's what these people are working on.

I've used "black swan" as code for "non-restricted number system (familiar from, e.g., Indo-European languages)", while Bloix' usage was probably something more like "Australian Aboriginal language that has a non-restricted number system". By which I mean: yes, I know what a "black swan" is, but I don't think that's what's going on in this particular case. That's why the world in my analogy contained black swans outside of Australia.

There are definitely interesting questions to be asked about these non-restricted number systems (this is not my area of expertise, so for all I know, people have!): What were the mechanisms of their evolution — if some members of a language family have small number systems and other members of the same family don't, what does the history of that language family look like? What similarities or differences are there between these Australian non-restricted systems and non-restricted systems in other language families? (etc.) But these are not questions you would expect to see addressed in a paper that's specifically about restricted number systems.

It's not as though the existence of Australian languages without small number systems invalidates the work of Bowern and colleagues. It has no bearing on the behavior of numerals in languages that do have small number systems. If there's such a thing as "the linguist position" on this issue, I think that would be it.

Adrian Morgan said,

September 6, 2016 @ 5:15 pm

I read this last night, before there were any comments, and decided that a lot of things were unclear and that I should come back after the comments had hopefully illuminated some points. The Facebook link is not accessible without an account so I couldn't check the context of the cited conversation.

I did notice at the time that the article linked to from the phrase "still didn’t extend past 20" does mention "20" or "twenty" (as anyone can verify with a text search), and of course I understood that strict Popperian falsification is inapplicable to the validity of a statistical generalisation (even in physics). It is plainly preposterous to pretend that Zhou/Bowern had claimed that some universal law prevents Aboriginal languages from having numbers greater than twenty.

But I still had questions, e.g. regarding the validity and prevalence of Norris's counterexamples. The comments have helped, but I have more to learn, and so will keep watching this thread for another day or two.

GH said,

September 6, 2016 @ 5:28 pm

@Mark F:

One paper that kind of touches on that is the one by Bowern & Zentz (2012) that provides the data for the Zhou & Bowern article: "Diversity in the Numeral Systems of Australian Languages." It discusses composition, bases and additive series, although at a rather high level. It also makes it clear that Bowern is perfectly familiar with the exceptions Norris cites.

I do think it's a little sloppy to not mention those outliers even in passing in the present paper, whether or not they're central to the argument being made. For Norris this is clearly something of a pet peeve, and I can understand that he dislikes what he sees as the promulgation of a misconception. It's not so different from the numerous LL posts railing against yet another example of Eskimos having N words for snow: it's not merely a matter of an incorrect factoid, but an expression of a whole line of thought that the critic finds obnoxious.

Of course, the rant about the lack of empirical rigor in anthropology (and linguistics?) is entirely unwarranted at least in this particular example. Apart from being naive about the methods of data gathering in the field, it has nothing to do with the question at hand.

Rubrick said,

September 6, 2016 @ 5:42 pm

A couple of additional relevant xkcd comics, because why not?

https://xkcd.com/263/

http://xkcd.com/435/

Y said,

September 6, 2016 @ 7:19 pm

Bowern and Zentz (2012), p. 136:

Those darn physical scientists never read footnotes or bother to look up references.

Chris C. said,

September 6, 2016 @ 7:49 pm

@KeithB — On his own account Feynman had figured out Mayan numerals as a kind of puzzle, not as a putative linguistics expert, and had sufficient layman's knowledge of what they applied to that he understood what they meant. I'm not sure he ever held himself up as any kind of expert on the subject, although others probably did due to the Nobel aura.

@Jonathan Badger — Ironically, it's Feynman's field which is now reluctant to engage in replication, mostly because high-energy experiments are so very expensive to run. (It wasn't an essay though, it was a speech, and at least partly off-the-cuff. I like to think that had he been better prepared, he's have also done a better job fact-checking.)

Michael Watts said,

September 6, 2016 @ 8:48 pm

Jonathan Badger:

Considering that psychology as a field is currently experiencing an epic meltdown where experiments traditionally considered core to the field just don't replicate, Feynman may have been on to something.

Gregory Kusnick said,

September 6, 2016 @ 9:56 pm

Leaving aside the question of Norris's linguistic competence, the fact that he wrote the above, apparently with a straight face, doesn't inspire confidence in his physics expertise.

Claire Bowern said,

September 6, 2016 @ 10:37 pm

Thanks all for interesting comment on Norris' piece, and to Mark for the laugh from the comics. The Facebook link is only visible to friends; it's not public.

Briefly, we didn't talk about the higher limit systems (much) in the Proc B paper for a few reasons:

. I'd already written two papers about typologies of Australian numeral systems, which include discussion of the larger systems. We discussed that briefly in the supplementary materials. We probably could have made that a bit clearer but we figured we'd already gone over that. We didn't include body tally systems, cattle counting, birth order names, or other types of enumerative systems because we were looking at numerals.

. The Proc B paper was about variation in the lower limit systems (we grouped all languages with limits above 8 together). Our point wasn't to establish the upper limit of extant Australian languages (as previous posters have mentioned, that's not a very interesting question) – we wanted to look at how the low-limit systems varied and what we could reconstruct.

. We were looking at Pama-Nyungan; Tiwi's not Pama-Nyungan, so wasn't part of the sample.

. We didn't include the systems that are based on English loans or calques based on shapes of Arabic numerals, for the obvious reason that (interesting though they are) they aren't likely to tell us much about Proto-Pama-Nyungan.

Skittish said,

September 8, 2016 @ 3:18 am

Ouch. My undergraduate degree is in physics — I laughed and cringed when I first saw the xkcd comic a while back. In defence of physicists, some of this behaviour isn't due to a sense of superiority, but rather their training kicking in (and their curiosity). On any one day during a physics degree, you could spend time in the lab studying signals, then spend some time looking at the equations of black hole formation, and afterwards try to understand spacetime. By looking at such a variety of subjects (physical objects in the universe, at any scale!), you tend to lose inhibitions about problems and try to create a simple model for any object/system you find interesting. I realise this can annoying, but if applied appropriately this mindset can be helpful, and many physicists have made successful transitions to other fields and professions.

Skittish said,

September 8, 2016 @ 5:04 am

Sorry to leave a second message, but I should add that my comment was a personal opinion, lest it comes across as phys-splaining.

leoboiko said,

September 8, 2016 @ 9:40 am

@Skittish: It's not a problem that physicists get curious about other areas, and then try to model them using techniques of the kind they're familiar with. It's not a problem at all! On the contrary, it's a good thing! Academic cross-pollination can only add, never subtract; and many great stuff in linguistics came from other fields (cognitive linguistics is predicated on cog-sci; historical linguistics and archaeology can validate or falsify each other; math and stat and comp-sci do all sort of things for us, e.g. we got a lot of interesting stuff from information theory, and data-handling techniques are a necessity for corpora studies; the accumulated knowledge of acoustics (drawing from physics) and auditory perception (from bio) form the basis of our understanding of phonetics…)

The problem is when people without any specialized background simply refuse to engage with a mature, thriving, complex scientific literature, and then jump to conclusions. Do you see any quantitative, data-based models in Norris' diatribe? Where he proves that Scientists Are Wrong by citing a couple anecdotes against an absurd strawman? What physics-based insight did he offer, exactly? One awful joke about "collapsing the wavefunction" (I really hope it's a joke)? One quick glance at Bowern and Zentz's paper will show that claiming it "doesn't engage with evidence" or "isn't based on data" is an utterly ridiculous accusation; and Norris' baseless vagaries about "post-modernism" and “the humanities” are simply preposterous. The only way Norris could reach such conclusions is if he didn't read the paper at all; it's the very definition of "I don't need to read your thesis, I can imagine roughly what it says." Norris is ignoring mountains of data, making all sorts of unsupported claims out of his purely subjective impressions ("Linguists claimed Aborigines can't count over 20" [no one ever did!!!] → "linguistic and anthropological theories aren't based on evidence" [just… stop… make it stop…]).

There's someone here who's imposing their personal narrative over fact, relying on fallacies over statistics, and making empirically testable assertions that happen to contradict the data. That person is a physicist. I guess physicists are all truth-denying postmodernists, am I right?

(P.S. not even postmodernists are "postmodernists", not in the way Norris imagine. $50 says he's never even read The Cambridge Introduction to Postmodernism nor a similar introductory manual, let alone the major works. Again, the problem isn't getting curious about other fields, the problem is the refusal to even read the things. This isn't just about physicists (consider all the nonphysicists who have misappropriated physics terms). Whenever one gets curious about a field of inquiry, one must start by reading the things; to fail to do so is the definition of academic hubris.)

Skittish said,

September 8, 2016 @ 11:23 am

Thanks @leoboiko, I find this kind of academic cross-pollination very interesting. I wasn't really referring to the article, but instead to the two cartoons that depict physicists as being convinced that they could easily solve big problems in other fields (I see a grain of truth in this openness to tackling problems, but wanted to mention curiosity as an alternative motivation to hubris, in some physicists at least). In my own case, I don't assume that I could solve the big puzzles, but I get enjoyment thinking about how I might go about solving them. However, I don't have the urge to criticise studies that I haven't done the requisite groundwork in (or at all really).

Ray Norris said,

September 8, 2016 @ 6:27 pm

As the "aging prof" physicist who is the butt of your linguistic comments, I feel a bit like Daniel walking into the lion's den! But I notice most of the comments above don't actually refer to what I said, but to some misreported version of what I said. What I actually said was this:

(a) there are many well-documented examples of Aboriginal number systems in the literature, by well-regarded academics, extending beyond five. These include base-5, base-10, and base-20 systems. There are also reliable accounts of no-base systems extending to 28, and well-documented accounts of special non-compound words for 20 and 100.

(b) There are statements in the literature which are inconsistent with this evidence such as Blake's "No Australian Aboriginal language has a word for a number higher than four." and Zhou and Bowern's “within Australia, the systems tend to be low limit (with an upper bound of less than 20, and frequently less than 5).”

I'm not actually taking a swipe at linguists, and I don't pretend to know anything about linguistics. I'm just interested in why the literature contains statements like that which appear to be inconsistent with the data. Can anyone explain to a poor ignorant physicist?

Adrian Morgan said,

September 9, 2016 @ 2:23 am

@Ray

Others will answer better, but just for starters, is the data inconsistent with the claim that the systems tend to have an upper bound of less than 20? Emphasis on "tend".

(I won't see replies, sorry, as I'm heading overseas shortly.)

GH said,

September 9, 2016 @ 4:12 am

I think the issue is that one plausible reading of that statement (perhaps the most plausible, in isolation), is: "Within Australia, the systems tend to be low limit. By 'tend to be low limit' we mean that their upper bound is frequently less than 5, and never higher than 20."

It's also followed by this: "First, we explore the phylogenetics of numeral system limits across the Pama-Nyungan family (the most populous family of Australian languages, covering almost 90% of the land mass and containing approx. 70% of Australian languages). Bowern & Zentz [14] show that upper limits vary from 3 to 20, with the median at 4."

I think the implied caveat here is "upper limits (where they exist) vary from 3 to 20," but this is far from obvious at least to a layperson, and I can't tell from the information provided whether Tyapwurrung has an upper limit (so that it would be an exception to the statement) or is in fact unbounded so that it falls outside of the discussion.

One of the other Bowern papers also makes it clear that "disconnected" higher numbers like 100 aren't counted if the number system doesn't provide a way to count all the intermediate numbers, which rules out one of Norris's other examples (Gurnditjmara), but that is left unmentioned here as far as I can see.

So I find it very easy to see how the paper could be misunderstood in such a way that Tyapwurrung and Gurnditjmara would appear to provide clear counterexamples to these claims.

David Marjanović said,

September 11, 2016 @ 1:55 pm

This looks like a culture shock to me. Linguistic publications are normally littered with footnotes that contain pretty important things which simply were a bit too hard to fit into the flow of a paragraph; they routinely spill over from one page to the next, and sometimes they take up more than half of a page. Journals for the natural sciences usually outlaw footnotes altogether, and even in those where footnotes are grudgingly allowed they're practically never seen. Any superscript numbers refer to the references list (if the references are numbered).

Oh no, that's not how CERN works. First, high-energy experiments are run in huge batches; then computers burrow through the Big Data the batch generated and look for patterns; then people try to explain the patterns. All experiments are replicated numerous times several months before anyone even looks at them.

leoboiko said,

September 12, 2016 @ 10:10 am

@Ray Norris: If you read the rest of the thread, or indeed the original paper, it should be already completely clear that Zhou-Bowern never claimed what you say they've claimed, viz. that all Australian languages only count to 20. In fact, when you say that they "don't even mention" evidence of higher-than-20 numerals, you're outright lying; see Y's, M.N.'s, and Bowern's comments above.

Your only other data point is a 1981 textbook. I don't know how far you're misrepresenting this 35-year-old textbook, because I don't have access to it; but it took me 5 minutes on Google Scholar to find a paper (John Harris, Facts and Fallacies of Aboriginal Number Systems) which cites it while mentioning higher number systems—in 1982, one year after Blake's assertion. You know, the scientific process. Someone writes a generalization, someone else points data which falsifies it, knowledge improves.

So let's recap. You've cited a grand total of two data points. One, from an outdated three-decade-plus-old introductory text, was refuted within a year, and never repeated. As for the other, the linguists did precisely what you claim they didn't, viz., engage with all the available data – they cite more evidence for higher-than-20 numerals than your vague anecdotes. Therefore, your examples of how linguists and "the humanities" "ignore" contradictory data are factually wrong – and quite extraordinarily so, given the amount of typological data that fundaments modern theories, not to mention database projects like WALS, or language revitalization/mapping/reconstruction projects. Even Z&B's paper, which you used as an example of those data-averse humanities people, was highly data-oriented.

From these two data points you extrapolate the following theory:

Do you have a peer-reviewed poll, or at least a quantitative literature review, to back up your assertions? Or do you just enjoy cherry-picking soundbites to proclaim the superiority of the “STEM master race” (never mind that linguistics is a science) against “humanities” softies on the popular media, stirring up vacuous debates based on your own personal prejudices? You lump linguists and anthropologists together with (your nonexistent, strawman, vague notion of) postmodernists; so you're being intellectually disingenuous when you later say that

If you really wanted to know this, you wouldn't post diatribes about how physicists are the only kind of scientist whose theories are falsifiable by data; you would instead have politely e-mailed Z&B (as pointed by Y above on his comment you how your "gotcha" approach is analogous to that of global-warming denialists). Z&B would have kindly explained your reading mistake, you would have learned something, and public hostility against humanities and linguistics wouldn't have grown even more. Instead, read the comment thread on The Conversation. Those are the results of your choice.

GH said,

September 13, 2016 @ 4:23 pm

False. It is not mentioned in the paper he was talking about, only in one of the references cited therein.