Chinese lesson for today

« previous post | next post »

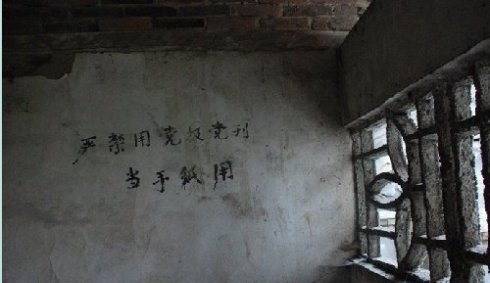

Sign on the wall of a public toilet in China:

Yánjìn yòng dǎngbào dǎngkān dāng shǒuzhǐ yòng" 严禁用党报党刊当手纸用.

Smooth translation: “Use of Party newspapers and magazines as toilet paper is strictly forbidden.”

Rough translation to reflect the redundant use of yòng 用 ("use"): "It is strictly forbidden to use Party newspapers and Party magazines for use as toilet paper." Stylistically it would be preferable to use ná 拿 ("take") for the first occurrence of yòng, and the second occurrence is not really necessary in any case.

Be that as it may, it is evident that some types of paper with writing on it are more precious than other kinds. In old China, one was not to wrap fish or wipe oneself with any paper that had writing on it, because writing itself was to be respected, no matter what the content or who the author was.

[A tip of the hat to June Teufel Dreyer.]

Evan Harper said,

August 29, 2010 @ 12:14 pm

God bless Canada, where we are free to wipe our behinds with any selection of Liberal, Conservative, NDP, Bloc, Green, or CPC(ML) newspapers or magazines. Personally, I prefer to use the Opinion section of the National Post.

groki said,

August 29, 2010 @ 12:36 pm

In old China, one was not to wrap fish or wipe oneself with any paper that had writing on it

what was the proportion of ephemeral vs for-the-ages writing "in old China"? were there, say, shopping lists or advertising flyers or broadsheets, or was most everything written some text worth keeping?

John Cowan said,

August 29, 2010 @ 1:41 pm

I have to say that the idea never occurred to me, possibly because the New York Times uses ink that notoriously rubs off on one's fingers.

richard said,

August 29, 2010 @ 2:29 pm

What I want to know is who is going to check?

Victor Mair said,

August 29, 2010 @ 3:02 pm

@richard

Let your conscience be your guide.

Endymion Wilkinson said,

August 29, 2010 @ 10:07 pm

In Beijing in the early 1960s, Chinese students at my institute used the Renmin Ribao (Party newspaper) both as lavatory paper and to stuff in the gaps between the windows and window frames in winter (to keep the warmth in) and in Spring (to keep the sand out).

Oh yes, they also used the Renmin Ribao editorials for study sessions.

As I recall, the newsprint was so faded that it did not cause smudging.

Endymion

William Page said,

August 30, 2010 @ 12:54 am

Here in Thailand, we have devised a solution to this nettlesome problem. Most toilets come with an attached hose, which permits you to clean your nether aperture (two, if you're a woman) by squirting water inside. If the pressure is sufficiently powerful, you don't need to use toilet paper at all.

Ben said,

August 30, 2010 @ 4:26 am

@richard: Many poorer areas don't have good plumbing, so used paper is thrown in a waste bin. And the Commies were nothing if not bloody-minded.

“Use of [Communist] Party Newspapers and Magazines as Toilet Paper Is Strictly Forbidden” | theConstitutional.org said,

August 30, 2010 @ 1:17 pm

[…] the text of a sign spotted on the wall of a public tolet in China, reports Victor Mair (Language Log). (Mair’s translation is just “party,” but I added “Communist” since I take it that this […]

Victor Mair said,

August 30, 2010 @ 2:30 pm

Around 20 years ago a satirical play called "Wǒmen" 我們 (Us / We) appeared briefly on the Mainland. As a matter of fact, THE OFFICIAL TITLE OF THE PLAY was "Women" (pinyin only). In the play, the characters used pictures of The Chairman and other symbols of party authority as toilet paper. Of course, it was swiftly banned.

Richard said,

August 30, 2010 @ 2:59 pm

I wonder in what era that was written. Even if it was 20 years ago, the characters may not have faded since it's on an interior wall.

Giorgio said,

September 2, 2010 @ 5:33 pm

IMHO, the first yong is actually a preposition and doesn't need to be translated, not even in the "rough" tranlation, as in: 以 … 用来 … yi… yonglai. Here I am not discussing the grammatical correctness of the sentence, but the reasoning of the author. Since yi is a (formal) synonym for yong, also yi…yonglai is redundant in my example, but you don't translate the yi and can be still accepted as grammatical. So the author may have substitued the formal yi with yong as preposition, and kept the last yong (predicate) notwithstanding the repetition.

We should also ask ourselves: for the author, is the repetition a problem of "how it sounds", or of "grammatical correctness"? Remember that the concept of grammar is of indo-european origin, and in the history of Chinese traditional linguistics there are no grammars in the indo-european sense until the late XIX century, because the "correctness" of a sentence was judged based on the imitation of a canon of "classics" of Chinese literature-cum-thought-cum-language.

Consider also that the author may have assumed that his/her intended readers may have better understood a sentence which is less formal/literary than a correct alternative, so he/she might have thought: better a sentence which is 不好听, than a formal one which does not work.