Modal deafness

« previous post | next post »

The business about musical modality and emotion reminds me of an amazing unpublished experimental result. At least, it's amazing if it's true; and I think it probably is.

Thirty years ago or so, microcomputers were just being invented, and most of them didn't have audio I/O, and none of them had much in the way of software for creation and manipulation of sounds. So researchers interested in audio analysis or synthesis wrote their own programs — usually in Fortran or assembly language — on suitably-equipped "minicomputers", which despite the prefix mini- were rather large and expensive devices. Both the hardware and the programming skills were hard to come by, and so when I was first at Bell Labs, the word got around that I was willing and able to help people make stimuli for acoustic perception experiments.

At one point, a grad student in psychology at Yale got the idea to see whether the phenomenon of "categorical perception" applied to tones in the context of musical chords. His basic idea was to create a continuum of stimuli from (say) a major triad to a minor triad, with the middle note moving in steps of (say) a tenth of a semitone from a minor third to a major third relative to the root, and then to compare discrimination and classification accuracy along this continuum. He asked for help, and so I made him a suitable set of stimuli (using Max Mathews' MUSIC program on Peter Denes's DDP-224), and sent him happily back to New Haven.

But a couple of weeks later, he was back with bad news. To screen his subjects, he'd run them first in a simple ABX discrimination task on the two end-points of the continuum. These subjects were the usual undergrad psychology students, further selected as having normal hearing and being especially interested in music. However, most of them did surprisingly badly, on a task that should have been trivial, and about a third of them performed at chance levels. So he figured that we must have screwed up the stimuli.

But analysis on the computer showed that the chords had the pitches that they were supposed to have. So we figured maybe it was some problem with the digital instrument I used — not enough higher harmonics, chords too long or too short, excessively regular phase relationships, something. We tried lots of alternatives, including chords played on a regular acoustic piano. Unfortunately, the result didn't change. It seems that this is a surprisingly hard task, at least for some people.

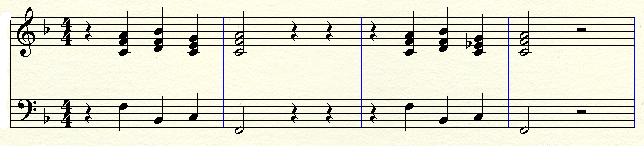

Just to clarify what's going on here, in the simplest case you're asked to tell whether two triads in root position — two major, two minor, or one of each in either order — are the same or different. You don't need to know the terminology, you don't need to identify which chords belong to which categories, you just need to tell whether two short, adjacent sounds are the same or different. In a simple same-different presentation, we're talking about things like this:

|

versus this:

|

I was frankly incredulous.

How could someone who enjoys listening to music not be able to hear that? It's a sort of masking effect, apparently, because the same subjects performed perfectly if the middle tones were presented independent of the other two notes in the triad:

A post-doc then in residence at Bell Labs was equally incredulous when I told her about this result. But when she listened to the stimuli, she turned out to be one of those who couldn't reliably hear the difference. She insisted that the stimuli must be faulty, despite all the checks and re-checks.

So we found a piano in a decent state of tune, and ran a quick test using pairs of chords played live. Same result — it was trivial for her to discriminate two piano notes in isolation a semi-tone apart, but when the same notes were played as the middle note of a triad in root position, her discrimination performance was at or near chance.

She was embarrassed and annoyed, and we agreed that this was all bizarre and weird. She had taken piano lessons as a child, she could sing well, she had a subscription to the symphony, she enjoyed listening to recorded music… And never mind all the happy-sad stuff, the different chords in question often play completely different roles in the syntax of tonal harmony. Was it really true that she couldn't perceive the tonal structures of the music that she loved to listen to? Was it all just percussion to her?

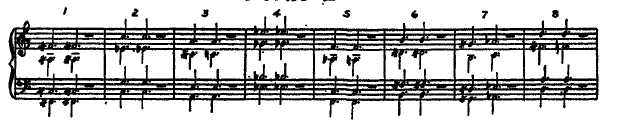

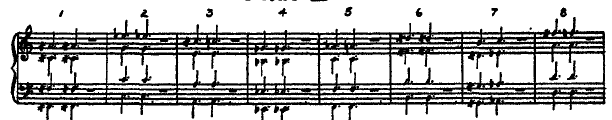

Neither of us could believe that, and so I tried something else. I embedded the same (major or minor) triads in a stereotypical I-IV-V-I cadential sequence, where the (flatted or unflatted) third is the leading tone of the V chord:

Suddenly, the difference was crystal clear to her. Never mind discrimination, she could unerringly identify the valid cadences. This is a classic example of "release from masking" — the difference between the two notes is trivially perceived in isolation; then the difference is masked when the same two notes are embedded in a chord; and then the difference is trivially perceived again when three additional chords are added in sequence.

I made up some new stimuli and showed them to the Yale grad student. He was interested, but (as I recall) his advisor thought this was a distraction — at best an echo of gestalt principles that were rather out of fashion in those days — and so I don't think any of this stuff was ever published.

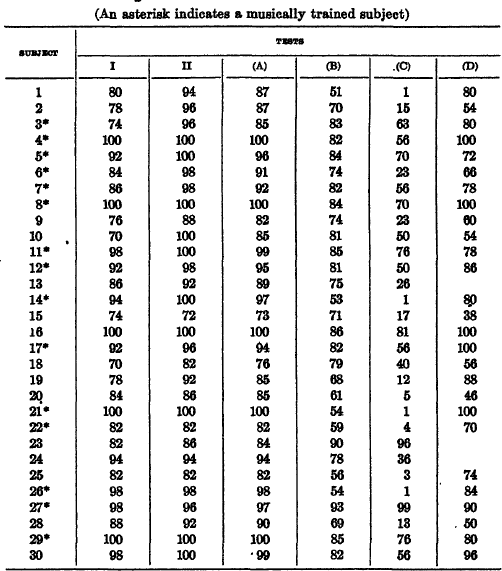

But one of the things that I learned by checking the references in the Bowling et al. paper is that a similar result had been published decades before I was born, in Christian Paul Heinlein, "The affective characteristics of the major and minor modes in music", Comparative Psychology 8(2):101-142, 1928. Heinlein performed

… a group of preliminary tests designed for the purpose of ascertaining degree of difficulty in discrimination between major and minor chords when presented in (a) the tonic open position with the root repeated in the soprano, and (6) in the tonic open position with root doubled in the bass and the fundamental triad Third introduced in the soprano. […]

In each of these forms, two pair-types are included. The first type represents a pair in which the chords are identical in their tonal structure: the second type represents a pair in which the chords differ from each other through the alteration of the triad Third by a semi-tone ascent or descent. Such alteration transforms a major chord into a minor chord, or a minor chord into a major chord, either chord being founded upon the same fundamental as root.

Note that these both of these chord-structures ought to be perceptually easier than the triads that we used, because in the first type, the third is further in pitch from the other notes in the chords,

and in the second type, the third also appears as the highest note ("soprano") in the chord:

Still, according to Heinlein,

The results, although evidencing marked individual differences in response, emphasize one fact; namely, that both trained and untrained subjects find it easier to discriminate between two chords in the inverted position [with the third as the highest note] than in the tonic position [where the third is an inner voice].

And the overall level of performance in "major-minor modal discrimination" was consistent with the results from the Yale undergrads. Here's the relevant table of results from Heinlein's paper, with the percentage scores for "major-minor modal discrimination" in column (D):

Note that 7 out of his 30 subjects performed at or below 60% on this task, and that several of the musically-trained subjects performed in the 60-80% range.

Nicholas Waller said,

January 25, 2010 @ 7:56 am

Unlike your post-doc I have no known musical or singing ability, though I like music, yet I can easily tell whether the first chords, the "two short, adjacent sounds", are the same or different – it stands out a mile, as distinct as the single notes. But your I-IV-V-I cadential sequences sound identical to me – I can just about persuade myself that they could be different, but it certainly is not trivial and probably only because I am told they are.

speedwell said,

January 25, 2010 @ 8:23 am

I was a classical piano/choir major, trained practically since birth to recognize music (my mother's family were songwriters). I never, ever had any trouble understanding or even vocally reproducing major/minor tonalities, even though it's been twenty years since my last piano lesson and I am a trifle deaf at high frequencies (nothing you would notice without an ear test).

Your examples of the similar and different chords are as different to me as two different colors… pure red and pure blue, say. But the sequence examples in which the chords are embedded… I have to say they are like a less-pure red and a less-pure blue, and the direction of the impurity is very slightly toward purple in both cases. (This is an analogy; if I'm a synesthesiac, I'm at best slightly to the right of the overall mean.) I have no trouble hearing and navigating the sort of Baroque or modern music in which major and minor simultaneously "cross;" I was actually bemused by an NPR program a few days ago that made much of that sort of thing. Now I know why it was such a big deal.

le_sacre said,

January 25, 2010 @ 8:28 am

In music theory lab classes, I always found the longer "harmonic dictation" exercises to be extremely difficult, because I was seemingly deaf to some aspect of the chordal language of music; to succeed, I had to listen and notate each voice of the harmony separately (as if it were a melody by itself), constrained by what I knew about how chord progressions generally go. In contrast, it seemed to me that the students who had more rock/pop/folk music backgrounds generally did this quite easily–my background was strictly "classical," which these days doesn't put much emphasis on improvisation or picking up chord changes.

I was also interested in the varying degrees of tone-deafness that manifested in the class. For most of us, learning to identify intervals (two tones played together or in succession) was not hard (and in contrast to my harmonic dictation frustration, I could do this easily), but for a couple kids it was just impossible. They also tended to be the ones who can't sight-sing at all, or even accurately sing back a pitch that's given them. I can't help but wonder what music *sounds like* to them, but I guess as a qualia question it's fundamentally unanswerable. I know at least one such tone-deaf guy who was a very passionate and committed listener and instrumentalist (though he did tend to play out of tune).

Sili said,

January 25, 2010 @ 8:47 am

I have exactly the same reaction as Nicholas Waller. No musical background or ability, but I know what I like.

The chords are easy to tell apart – alike or different – I couldn't identify them in isolation, I'm sure. But the melodies are indistinguishable. I have fairly good earphones, but it doesn't matter if I use both or just one ear: damm-Damm-damm-DAMM.

Sili said,

January 25, 2010 @ 8:57 am

Just to stress the lack of understanding: I consider myself fairly well educated and educatable, but it seems that no matter how often I read about music, I get lost. Major, minor, triad, tonic &c are Greek to me – or worse, since I at least know the Greek alphabet.

marie-lucie said,

January 25, 2010 @ 8:58 am

The experiments refer to subjects with "musical training", but there may be a difference between singers or those who play instruments which only produce one note at a time, like the clarinet, and who therefore are trained to produce or attend to the melody, and those who play keyboards or guitar and therefore are trained in playing chords as well as the melody. I don't mean playing chords just as an accompaniment to a melody, but also chord sequences in which a primary or secondary melody is carried by the inner voice (as in some Chopin pieces, for instance). For the piano this means a more advanced level than just a few lessons in childhood.

Also, I wonder if the experiments went beyond identifying the difference between two musically possible sequences (as in your examples of single chords or cadences) and between jarring sequences where the "wrong" chord appears, or where the same chord should be played by both the right and left hand (as at the end of a baroque piano piece) but a "wrong" note is played in one of the hands.

Bryan said,

January 25, 2010 @ 9:36 am

This is interesting, but also surprising. I can't make the chords in isolation sound the same even if I attempt to not pay attention, they are starkly different to my ear. On the other hand, I did not notice the difference in the chord progressions at all the first time I played them. For reference, I was briefly a music student, many years ago. It was indeed an inability to progress at ear training (specifically, identifying chord progressions) that did me in, despite many hours spent in lab and a thorough grasp of music theory (I eventually found a better home in math and physics). I am definitely curious as to what discriminates these musical abilities in different individuals.

Army1987 said,

January 25, 2010 @ 9:51 am

If I hear a major chord and a minor chord in succession, I can easily tell them apart; but I'm testing myself to recognize such chords played each in a random key using GNU Solfege, and until now I only recognized correctly 14 out of 26 major chords, and 14 out of 22 minor chords.

Ray Girvan said,

January 25, 2010 @ 10:03 am

Very odd. I can hear the difference clearly both in the triads and the melodies – and it's definitely at the level of "almost can't imagine how anyone couldn't". The musical background aspect does look worth investigating – as marie-lucie says, single-note vs. multi-note instruments, and so on. Mine is piano in teens, plus choral/folk singing (e.g. improvising harmonies unaccompanied) and busking-level piano accordion. I say "almost can't imagine" because I have over the years run into a few musicians who were a billion times better technically – for instance, I've never been able to properly sight-read in real time – but had surprisingly little "ear" for pitch and harmony.

Mary Bull said,

January 25, 2010 @ 10:50 am

I wonder how much the characteristic popularly referred to as "perfect pitch," or sometimes as "absolute pitch," plays into this modal recognition ability. I am one of those who do possess the trait — identified in me by my piano teacher at age 5. I didn't expect to have any difficulty in discriminating between the major and minor triad chords — but, given the experience described by others, was prepared to be surprised.

However, there was no surprise. I heard the differences clearly in every example — indeed, because of my absolute pitch, I heard them "in my head" before I clicked on the audio "buttons."

Have there been any research experiments that tested only subjects with "absolute pitch"?

Amy Stoller said,

January 25, 2010 @ 11:09 am

For me, differences between triads, single notes, and I-IV-V-I sequences all glaringly obvious, but of course I cannot know whether that's because I read your entire post first. I have been told, by people who should know, that I had "perfect" pitch as a toddler; I certainly don't now (a case of "use it or lose it).

In case it's important, I played piano (reasonably well) age 5-8, and acoustic guitar (not in my estimation, not nearly so as well as piano) for about three years during the Kumbaya Era.

I sang in choruses for nearly 10 years, also in madrigal groups, so perhaps my practice in singing harmony helps. Darned if I know what this all means, but it is interesting.

You might be interested in contacting Richard Armstrong at NYU about his experiments in correcting, or perhaps I should say freeing people from, so-called tone-deafness. I once observed him release a number of people who had been told they were tone-deaf into an awareness that they could reproduce pitch wonderfully accurately. It took ten minutes. It felt like a miracle. I'll never forget it.

Incidentally, I'm just parroting your terminology. My acquaintanceship with music theory stopped even nodding, long, long ago.

Clive said,

January 25, 2010 @ 11:14 am

I have the same experience as Bryan. The chords played in isolation sound very different, the progressions do not! I have no musical training at all.

John said,

January 25, 2010 @ 11:50 am

Wow, I'm very surprised by these results. It's glaringly obvious to me that the first examples are different, but like some of the other posters, the embedded examples are much less so.

I took a music class in college and sang in a glee club all the way through, with voice lessons. Also a mediocre guitar player. Mildly musical, I'd call myself.

Ben said,

January 25, 2010 @ 11:51 am

I played violin growing up, sang in a choir in high school, and taught myself some guitar in high school. But I was never particularly good at any of it. (Like Ray Girvan, I could never sight-read in real time, for example. Not even close.) The difference in the triads and the single notes was unmistakable to the point where I found it hard to imagine not hearing it. The difference in the chord progressions was noticeable, but I could imagine not hearing it. Like Amy Stoller, I wonder what effect reading the post had on my perceptions.

John Gutglueck said,

January 25, 2010 @ 12:05 pm

I'm not sure that modal deafness aptly describes your Bell Labs colleague's disability. She seems to have been able to distinguish the major (or Ionian) mode of the I-IV-V-I progression from the Mixolydian mode of the I-IV-v-I progression. [Note that while the major third of the V chord is indeed a leading tone (of the scale, not of the chord), the minor third of the v chord is not; it's a subtonic.] What your colleague couldn't distinguish was rather the difference between the qualities of two chords built on the same root. So maybe chord-quality deafness?

One drawback of the I-IV-V-I vs. I-IV-v-I experiment is that the stimulus doesn't juxtapose major and minor chords on the same root as the stimulus of the earlier experiment did. It would be interesting to know whether your colleague could have recognized the difference in chord quality when such juxtapositions occur in a larger musical context. Would she, for instance, have discerned the change of quality in the juxtapositions of tonic A major and A minor chords in the fadeout of the Beatles' I'll Be Back? In the dramatic progression from a tonic E major to a tonic E minor between the verse and bridge of Norwegian Wood? In the juxtaposition of major and minor subdominants in the V7/IV-IV-iv-I progression heard in songs like If I Fell, In My Life, Magical Mystery Tour, etc.?

David L said,

January 25, 2010 @ 12:20 pm

Another anecdotal data point: I like (various kinds of) music, but have no musical training or ability, and despite repeated attempts have never been able to grasp the distinction between major and minor, let alone more complex stuff.

That said, I easily detected the difference in the first test and only slightly less easily heard it in the second. Does this make me some sort of musical idiot-savant? Cool!

Matt McIrvin said,

January 25, 2010 @ 12:37 pm

It was also a little harder for me to hear the difference in the cadential sequences than in the isolated chords. But I'm also wondering how I would have done a year and a half ago, before I started practicing the guitar (and learning a lot about chords).

It might be interesting to test people trained in classical music vs. people mostly familiar with popular music on the cadences. In modern (post-Beatles) rock, songs frequently "borrow chords" from the parallel major or minor to the main key of the piece, or even from the parallel major/minor to the relative minor/major; so "wrong" chords appear more often than in traditionally tonal classical music and might sound less wrong.

Linda said,

January 25, 2010 @ 12:40 pm

@ le_sacre.

You asked what music sounds like to those of us who have problems with pitch. The answer is pleasant, but we are enjoying different aspects of the composition.

I need a whole tone difference even to know two notes are different, and more than that to be able to say reliably which is higher. I also cannot relate notes played on different instruments, so I would never be able to tune a string to the same note as a flute. I could however distinguish between a plastic and a wooden recorder playing the same note.

So while pitch is of lesser importance to me in music, the shape of the sound and combination of overtones produced by the instruments does effect how I hear music.

Steve Harris said,

January 25, 2010 @ 12:58 pm

My background is playing flute since childhood, choral singing for 25 years; I'm a lifelong enthusiast of classical music. I'm in the category of hearing the chordal distinction as brilliantly stark, the progression difference as much more subtle difference (though still clear).

By my count, here is what I see in the comments to date (12 commentors having given their self reports):

5: chordal distinction EASY, progression distinction HARD

4: chordal distinction EASY, progression distinction MODERATELY DIFFICULT

3: chordal distinction EASY, progression distinction EASY

In particular, none of the 12 have had the least trouble distinguishing major vs. minor chords in isolation, and it would appear puzzling to all of us how there could be an unmasking effect from embedding what "ought" to be readily distinguishable chords in a melodic progression. So the comments leave me as bemused by the post-doc's experience as I was after just reading the main body.

[(myl) It was also the experience of the undergrad experimental subjects, and also some of of Heinlein's 1928 subjects. Of course, those tasks were somewhat different, in that they involved hearing lots of pairs in different keys, and (in the 1928 case) in different inversions.

But the pattern of finding the cadences harder than the isolated chords is less weird than the opposite, obviously.]

Boris said,

January 25, 2010 @ 1:04 pm

I have near perfect pitch (I can identify a note played in isolation to within half-tone, but unlike those with perfect pitch don't find it difficult to follow a transposed melody) and I have classical training, mostly in violin, but also the piano, plus music theory (though it's been years since I've used any of it). I can easily tell the difference of the chords in isolation. In the progression, I can also hear the difference (maybe not as clearly), but cannot necessarily say what the difference is without repeated hearings.

Sanna said,

January 25, 2010 @ 1:07 pm

[Ray Girvan said: …and it's definitely at the level of "almost can't imagine how anyone couldn't".]

My husband and I just listened to all the audio clips on this page. I had five years of childhood piano followed by six years of jr+high school oboe, my husband had six or seven years of jr+high school cello plus two years of in-his-spare-time instruction in college. Neither of us have played anything extensively in the last ten years, altho I occasionally listen to the radio in the car, and he has Pandora on at his work 8-10 hours a day. (Lots of 'in', very little 'out'.) Furthermore, my husband seems to … not have the strongest judgment of when a note is too sharp or too flat.

Neither of us could imagine anyone with a basic understanding of music could /not/ hear a difference in the "two major" vs "major-minor" chords. A person might not fully understand what the difference was, especially if they had not seen the notes, but how a person could hear those two-and-two chords and think that all 4 were exactly the same… That boggles me. The last chord is /clearly different/.

Does this make us special? I wouldn't have thought so. It seems so simple to me; I would never have thought that it was… noteworthy? I would be interested in submitting to a test like this, because now I'm very curious to see how I would fare.

Ben said,

January 25, 2010 @ 1:09 pm

To me, the difference in the tones was easily discernible both embedded in triads and in isolation. And like another commenter above, it would be obvious even if I wasn't paying attention. And I have absolutely no training or skills in music.

So either I am misunderstanding the article, or (as evidenced by me and everyone else here), there is something different about the audio clips above that make the differences more discernible than in the original experiments.

Embedded in the longer sequences, however, it was very difficult for me to notice a difference. Upon my first listening, the two sequences sounded identical — I could only tell a difference by putting a lot of concentration and listening at exactly the right spot. And because of this, I can't even be sure I didn't make up the difference (because when you are looking for something with that much concentration, you often find it whether it is there or not).

Steve F said,

January 25, 2010 @ 1:20 pm

If I understand correctly, most of the commenters (including me) have exactly the opposite experience to Mark's colleague – we can hear the difference quite easily in the chord, but find it more difficult in the cadence. For myself – entirely untrained musically, but a keen listener and concert goer (jazz as well as classical) – the difference between the two chords was unmistakable, though I wouldn't necessarily have been able to identify them as major and minor. The difference between the two individual notes was also absolutely clear, and I think I might even have known that the interval was a semi-tone. As for the two cadences, I can hear the difference – unlike some commenters here – but I certainly found it harder than in the chords, let alone the single notes.

This experience seems natural to me – it's easiest to distinguish single notes, slightly more difficult when they are the middle note in a chord, and slightly more difficult still when they are part of a sequence of chords. The experience Mark recounts where the cadences were easier to distinguish than the chords strikes me as very odd.

Mark Yeary said,

January 25, 2010 @ 1:39 pm

It seems that if the context example placed the variable chord at the *end* of the chord progression, it would be as easy–perhaps easier–to hear as the isolated chords. One recent study used this format to examine category effects for chords with variable thirds, much as described above: DOI: 10.1080/03640210802222021 (Note that the subjects were all music majors in their second year of harmony.)

I've just recently completed a study that used isolated chords, in which participants were asked to recognize a tone within a chord, and nearly a third of my participants did not progress beyond the training stage. (And yes, most of these non-progressors had plenty of musical training.) Hearing a chord in isolation is not a familiar experience for most people, even music aficionados; unless you've been training specifically to make such isolated discriminations, as with many ear-training classes, then such a task would be on par with distinguishing neighboring vowels in an unfamiliar language.

michael farris said,

January 25, 2010 @ 1:44 pm

I find the chord difference very, very easy to hear and have trouble imagining anyone not hearing it. The sequence sounds less different but I have still hear the difference easily enough.

As a child, I scored well enough on a musical aptitude test we were given in school, that my parents were contacted and encouraged to get me training, which didn't really happen. On the other hand, when I did try to learn to play a musical instrument I didn't set the world on fire. After failing at trying to learn guitar I played flute and later saxophone in band at school. But I was never better than mediocre (and that's being a little generous).

Chris said,

January 25, 2010 @ 1:54 pm

Many times I've found guitar tabs online with a minor chord mistaken for a major. It sounds completely wrong (to me) when played, and I've always wondered how anyone could miss it.

Jay Livingston said,

January 25, 2010 @ 1:57 pm

What would the results would have been if the chords had been held for longer duration?

I, too, could hear the difference both in the simple triad and in the cadence. But I wonder if I would have heard it so clearly had I not read about it first and seen the music.

[(myl) There are lots of relevant variables — the duration of each chord, the interval of silence (if any) between them, the timbre of the "instrument" used to play them, the octave in which the chords are sounded, the spacing and possible doubling of some of the notes, the nature of the task ("same/different" vs. "AB-X" vs. "which of these three is not like the others"), etc.

And I need to emphasize that this whole thing is based on my memory of some interactions that took place about 30 years ago, not the determinate results of a well-documented experiment.

Still, the results in the 1928 paper do suggest that for some fraction of the population, simple same-different discrimination of major and minor chords is a surprisingly difficult task.]

Matt McIrvin said,

January 25, 2010 @ 1:57 pm

I would think the more interesting contextual effects would come from venturing beyond the I, IV, V chords. In the major scale, the chord on, say, the second or sixth degree is actually a minor chord. (As just one example, the "Fifties progression" from a million sugary doo-wop songs has a minor chord in it: I, vi, IV, V.) Played in the context of a larger tune in that key, in which the minor chord contributes to the "majorness" of the whole piece, I would expect it to convey a much different affect than played in isolation.

That even suggests a hypothesis about what was happening to the postdoc: she may have been trained to listen for the tonality of a whole piece, in which case the isolated chord was ambiguous. Putting the minor chord into the cadence, on the other hand, makes clear what musical function it's supposed to be playing, and suddenly that one different note makes the whole piece sound something other than traditionally major-keyed (Mixolydian, I believe).

Where Listening Gives Rise to Silence and Fizzles « The Coming of the Toads said,

January 25, 2010 @ 2:05 pm

[…] one distinguishes sounds, as in the experiment discussed over at Language Log, might explain musical preferences. Listeners who prefer a country western song, such as Hank […]

Sili said,

January 25, 2010 @ 2:08 pm

I know it's beyond a breakfast experiment, but I'd love to test myself on more than the one chord. And blinded, of course.

I've tried the 'perfect pitch' survey linked and discussed here a while back, but this seems to me a simpler (and easier!) exercise.

Would a kind reader code up an informal survey for us poor unmusical fans?

George Amis said,

January 25, 2010 @ 2:23 pm

Another few data points: I found all of the distinctions trivially simple, but I found the cadences a trifle harder. (I have played at various times piano, various woodwinds, guitar, piano and organ, and have done a fair amount of informal singing. I have an odd kind of precise pitch discrimination such that I can tune a guitar, for instance, very accurately, and I'm driven wild by people who play and sing off pitch.) My children, 11 and 14, with some piano and a good deal of piano respectively, found the chords easiest, the single notes a little harder, and the cadences harder still, but had no trouble with any of them. Neither could understand how anyone could fail to distinguish the chords correctly.

bfwebster said,

January 25, 2010 @ 2:37 pm

Interesting stuff. I didn't have problems hearing the differences in both sets, though in the second set, the differences are a bit more subtle.

My only music training comes from high school choir (and one semester of opera workshop my freshman year of college). Even now, I tend to sing more by ear — picking out my line from the accompaniment — rather than pure sight reading, which may explain why I can hear the differences.

Coby Lubliner said,

January 25, 2010 @ 2:58 pm

I find the post and the comments very interesting, but what caught my attention is unrelated to the substance. It's the turn of phrase I was frankly incredulous. I'm curious: what does frankly modify here? was, incredulous or the whole clause?

Spell Me Jeff said,

January 25, 2010 @ 3:00 pm

I have some musical experience and theoretical training. I also found the simple chords easy to distinguish, and likewise with that sense of "How could anyone not?"

The chords in context were a little different. I heard the difference, but it was less jarring than I had anticipated. The flatted chord sounded a little muddy, is all.

I wonder how much of the perception depends on Mark's choice of progressions. The basic blues progression is easily the most familiar to Americans. Two competing hypotheses come into play.

1. As soon as you hear the I IV, fans of pop know exactly what key we're in, and thus what notes are to be expected, and also what chords are likely to come next. V is a likely guess. So one would expect a typical radio fan to notice if a note is off in the dominant.

2. On the other hand, isn't it possible that the mind would be so expectatious (pace) of the Major V, that when it hears the minor V, it silently corrects the difference, and thus hears what it expects? (Much in the same way we correct for typos and such.)

I wonder if jazz or classical fans would be more or less attuned to the difference.

I also wonder if jazz and classical fans would be more or less attuned to the difference if it occurred in a progression that was less typical, in a context where breaking key is as much the norm as staying in key.

Layra said,

January 25, 2010 @ 3:29 pm

I think I find the cadence slightly easier to distinguish than the isolated chord (and less so than the single note), but not by much, and the difference is fairly clear to me in all cases. But I can sort of understand why it might be possible for people to not be able to tell; if I weren't primed for the difference and the situations not so simple, I might find myself unable to distinguish.

Background: nothing resembling absolute pitch, and my relative pitch is kind of shaky. Essentially no formal music training. I do, however, do music composition and so have some experience comparing and deciding between modes.

Army1987 said,

January 25, 2010 @ 3:58 pm

Was each subject exposed to the *same* major and minor chords over and over again, or was each of the chords in a randomly chosen key?

Rick S said,

January 25, 2010 @ 4:17 pm

I had no trouble hearing the distinction in any of the examples. I've never been able to play a chord-producing instrument decently, nor sight-read music (I have to work out each note individually and rely on muscle memory).

I may have one advantage over some others, ehough. I'm old enough to have actually had music class in grammar school, and I distinctly remember in 6th grade our teacher testing us on relative pitch discrimination. It was an epiphanic moment for me; I suddenly understood the connection between what I now know are called intervals and my fundamental internal response to them. It's similar to being able to sense the degree of tension in an overheard conversation. Sort of synesthetic, maybe.

Ken Grabach said,

January 25, 2010 @ 4:54 pm

I found both the chordal distinctions and the progression distinctions easy to recognize.

The varying results reported by the commentators, compared with the results of the unpublished study suggests this to me. In order to have a statistically significant result, the sample population needs to be much larger than probably was done. And as you say, there are so many variables. That could have been what was in the mind of the advisor when he suggested not continuing with the experiment.

My first musical training was on a wind instrument (cornet). From my teenage years I have been a chorus singer. I am able to hear pitches, but have no memory for so-called perfect pitch. I did learn a small amount about chords with a guitar, but this was long ago, and I've forgotten much of this.

Bob Ladd said,

January 25, 2010 @ 5:45 pm

You can add me to the list of people with musical training (and long choral singing experience) who found the isolated chords conspicuously distinct but the distinction between the chord sequences rather more subtle. This certainly seems worth following up.

Arjan said,

January 25, 2010 @ 6:27 pm

@marie-lucie: funny you mention the clarinet as example. I played the clarinet for over ten years, but other than that I really don't know much about chords, etc. But I can very easily distinguish between the samples of chords posted here. Interesting, I can't even see how one would not take notice!

Ellen K. said,

January 25, 2010 @ 6:33 pm

I think it's a matter of one listens to it. We, from having read the post, and seeing the graphic, are primed to listen to the middle note. But, I can make myself listen differently, listening to the root, and the difference between the two chords is less distinct.

dw said,

January 25, 2010 @ 6:46 pm

I found both examples as easy to distinguish as night and day — but then I've been playing classical music in various ways since childhood (at least until parenthood recently intervened). If anything the chords alone were easier to distinguish than the chords in sequence.

I wonder whether there is a "critical period" for musical discrimination, just as there supposedly is for phonemes? Try as I might, I cannot reliably perceive the distinction between all the aspirated/unaspirated, voiced/unvoiced, and dental/retroflex stops of spoken Hindi, although I can produce all the distinctions reasonably well and I fully understand the theoretical basis behind them.

peter said,

January 25, 2010 @ 7:08 pm

marie-lucie said (January 25, 2010 @ 8:58 am)

"there may be a difference between singers or those who play instruments which only produce one note at a time, like the clarinet, and who therefore are trained to produce or attend to the melody, and those who play keyboards or guitar and therefore are trained in playing chords as well as the melody. I don't mean playing chords just as an accompaniment to a melody, but also chord sequences in which a primary or secondary melody is carried by the inner voice (as in some Chopin pieces, for instance). For the piano this means a more advanced level than just a few lessons in childhood. "

The type of keyboard makes a difference. Because harpsichords can not sustain notes and do not enable notes played simultaneously by different fingers to be played differentially loudly, having an inner voice carry the melody is not something found much before the piano was invented – indeed, also not before a generation of pianists had grown up learning the instrument (ie, it is significantly more common in Mendelssohn and Chopin than in Mozart or Beethoven).

Skullturf Q. Beavispants said,

January 25, 2010 @ 7:19 pm

I had no trouble perceiving all the relevant distinctions in this post, and I enjoy music (and play guitar a little) but have no formal training.

However, I was reading the text and looking at the pictures in the blog post, so I knew what to expect. I'd like to believe that I'd also do well in a blind test where the contrasting sounds are played in random order — but there's a part of me that fears I might be closer to the annoyed Bell postdoc mentioned in the blog post.

uberVU - social comments said,

January 25, 2010 @ 7:38 pm

Social comments and analytics for this post…

This post was mentioned on Twitter by PhilosophyFeeds: Language Log: Modal deafness http://goo.gl/fb/EMC9…

David Eddyshaw said,

January 25, 2010 @ 8:01 pm

I'm another who found the isolated chords unmistakeably distinct but found the progression a bit less so.

(I'm the Zeppo of my family musically. Practically everybody seems to have perfect pitch but me, and everyone but me can play one or more instruments. But I notice the piano going out of tune well before anybody else does, and I found it fairly easy to hear the tone contrasts in the local language when we lived in Africa. Perhaps the progression recognition involves more actual musical sophistication than the simple chord distinctions?)

John said,

January 25, 2010 @ 8:17 pm

I wonder whether it would be worth posting new sound clips of the chords and single notes, this time with the silence interval a noticeably longer. To my ear, it sounds as if the second sound follows fast on the first. Maybe the output goes to 0 briefly, but it's only very briefly. Make it a second or longer.

kmurri said,

January 25, 2010 @ 8:52 pm

Just to add two more data points. . .

I found all the examples easy to distinguish, as did my partner. I have more music in my background that she does but we've both sung in choirs quite a lot. I also played trombone in jr high and guitar from HS on.

Bill Benzon said,

January 25, 2010 @ 10:50 pm

Mark Yeary: Hearing a chord in isolation is not a familiar experience for most people, even music aficionados; unless you've been training specifically to make such isolated discriminations, as with many ear-training classes, then such a task would be on par with distinguishing neighboring vowels in an unfamiliar language.

dw: I wonder whether there is a "critical period" for musical discrimination, just as there supposedly is for phonemes? Try as I might, I cannot reliably perceive the distinction between all the aspirated/unaspirated, voiced/unvoiced, and dental/retroflex stops of spoken Hindi, although I can produce all the distinctions reasonably well and I fully understand the theoretical basis behind them.

Let's forget about those who have no trouble distinguishing the isolated chords but have trouble with the chords in the context of a cadence and think about the Bell labs post-doc from back in the day. Think of the difference between a major and a minor third as being a distinctive feature (in the Jakobsonian sense) in Western tonal music. They are, in effect, the two values of a particular "phonemic" feature in that musical system. Those who have learned that system will thus be specially attuned to that difference while those who have not learned that system might well have difficulty distinguishing them.

The post-doc, of course, was familiar with the Western tonal system and could make the discrimation in a more or less "natural" musical context. But without that context it is as though her knowledge of the Western tonal system was not called upon. And so she couldn't hear the difference, just as dw can't perceive some of the distinctive features of Hindi phonemics. If this is what is going on — and I'm only guessing — then we'd like to know a bunch of things, starting with just why that musical knowledge wasn't evoked by the decontextualized chords. And so forth and so on.

I observe that that auditory nervous system has different patches of tissue specialized for perceiving different aspects of a sound stream. Some areas are specific to speech, some specific to music, some shared by both, some for other sounds (neither speech nor music) and so forth. If I were to take a serious stab at this problem I'd look into that literature and see what we know about individual differences.

Bill Walderman said,

January 26, 2010 @ 12:19 am

I play the violin (not professionally) and I have some knowledge of music theory. I have no problem hearing the difference between the major and minor thirds in the triads and the cadences, as well as in the sequences of two notes. But when I hear two notes a third apart sounded simultaneously ("double-stops," in string language), I have a lot of trouble telling whether it's a major third or a minor third.

Erin Jonaitis said,

January 26, 2010 @ 1:16 am

The initial experiment you describe sounds really familiar. I seem to remember a series of papers by Robert Crowder from the eighties that involved perception of chords along a continuum from major to minor. I can't recall if he found any evidence of categorical perception, though.

The effect you observed is interesting, too. Hmm.

Jerry Friedman said,

January 26, 2010 @ 2:06 am

@le_sacre:

I'm one of those people (and if I get the chance, I may prove it by listening to those chords). I agree that the question is unanswerable, but this might be an analogy: Anyone who knows the rules of chess can follow a grandmaster game and know exactly what's happening on the superficial level, but some will understand a great deal more than others.

Or maybe two people looking at a beautiful and informative map, one who has never been to the places and one who knows them well.

Minds are strange. I've read a couple books on harmony and tried my hand at simplistic composition. For some reason, nobody likes what I've written.

That's why God gave us the piano.

Marion Crane said,

January 26, 2010 @ 2:23 am

I have no trouble hearing the difference in the triads and the sequence of single notes, but in the cadential sequence the difference is very slight, and I might miss it if I wasn't actually listening for it. As for background, I played the oboe since I was 7 until real life intervened a couple years ago (and the lack of an orchestra to play with, it's just no fun by myself), and for most of that time I had some sort of musical education beside the oboe lessons. We practised quite a bit with stuff like this, actually, to hear the difference between major and minor, and intervals, so maybe that's why the triads in isolation sound so clear to me.

B.W. said,

January 26, 2010 @ 2:59 am

The difference in the chords and single tones is very clear to me, but I missed the difference in the sequences when I listened to them first. Even with repeated listening, I still find it hard to hear.

For what it's worth, I score rather low on a tonedeafness test (18th percentile), but perfectly average to slightly above on a pitch discrimination test (59th percentile), on a rhythm test (44th percentile) and on a musical-visual analogy test (75% correct, average 72% correct, no percentile ranges given). I took the tests on this website: http://www.tonometric.com/)

I'm intrigued by my scores because I'd like to know what makes the tonedeafness test different from the others. After taking a similar test a couple of years ago, I thought I had bad short-term memory for music, but the musical-visual analogy test computed a separate score for memory which was perfectly fine. I have no formal musical training – I simply can't figure out what makes one test harder for me than the others.

Paul Blankenau said,

January 26, 2010 @ 4:40 am

All the differences seem obvious. After a couple unmotivated years of piano as a kid, I started on my own a few years ago and proceeded, in spurts, to the point where I suck slightly less than I used to. I'd like to be able to play by ear, but I usually find it maddeningly difficult.. That tonometric site said I could discriminate to .75 Hz, and aced the visual analogy bit, but only OK to iffy on the others. I'll wait a good bit and try again when I don't have to worry about waking anyone, though I don't expect much change.

It is well known that most adults don't get enough sleep, mostly because of Mark Leiberman.

Fred said,

January 26, 2010 @ 6:15 am

Lifelong musical training here. All of the examples were easy to distinguish. Totally baffled that others can't hear them, particularly other musicians… unless they're guitarists! :)

co said,

January 26, 2010 @ 9:16 am

Yet another piece of anecdata: I've played piano since I was a child, sung as an alto in all kinds of musical groups both from written music and by ear, and accompanied traditional and contemporary church choirs. So picking out the difference was trivial for me – in fact, it's what my ear is drawn to. But … this could explain the puzzle of why very fine musicians find singing inner parts so difficult. I think I'm going to change the way I "drill the notes" to use cadences and see whether that will help. So thanks for the great information.

Bill Walderman said,

January 26, 2010 @ 10:51 am

"having an inner voice carry the melody is not something found much before the piano was invented – indeed, also not before a generation of pianists had grown up learning the instrument"

Off-topic but I couldn't let this go without comment. It may be somewhat true of keyboard music–I'm not sure. But not all music is keyboard music. Strings, winds, and voices can sustain notes, and good composers before Chopin, Schumann and Mendelssohn wrote interesting inner parts, even in chordal writing. Bach's chorale harmonizations–the gold standard and the textbook of tonal harmony–are largely chordal but the inner parts are always melodically interesting.

[(myl) Really. From the Wikipedia article on cantus firmus:

And the definition of the "fugue" form is a direct contradiction to the notion that "having an inner voice carry the melody is not something found much".]

TB said,

January 26, 2010 @ 12:01 pm

Another variable I would be interested in would be the tuning system. Would it be easier or more difficult in just intonation? Or perhaps it's more important what sort of tuning system you grew up with. I know very little about music, but it's my understanding that equal temperment has made us all rather accustomed to beating and the like.

Sridhar Ramesh said,

January 26, 2010 @ 3:29 pm

Just to add to the anecdotal evidence here, I have exactly the same reaction as Nicholas Waller and also everyone else. For me, the difference in the adjacent single chords and the adjacent single isolated tones is immediately obvious, while the difference between the I-IV-V-I sequences is much more difficult to hear.

speedwell said,

January 26, 2010 @ 3:58 pm

I posted before, but a couple things came up in the comments that were interesting:

I can't make out the subtler distinctions in Hindi either. I gave up, frustrated, when trying to learn from a CD course.

Even though I can hear and reproduce musical pitches, intervals, and rhythms without difficulty, I can't, CAN'T, do "accents." I can hear accents and tell you, to a first approximation, which general language group they come from, if it's common. But my father was Hungarian and I can't "do" a Hungarian accent. I lived in the Deep South for fifteen years and my poor attempt at a Georgia hillbilly accent sounds a bit like an Irish Russian with a speech deficiency ,played at half speed. I've been living in Texas for ten years now, and the only thing I've picked up is "y'all."

Steve Harris said,

January 26, 2010 @ 6:50 pm

On a purely linguistic note, examining Mark's reply to me:

"But the pattern of finding the cadences harder than the isolated chords is less weird than the opposite, obviously."

I had a difficult time unpacking this sentence. It means (approximately) that distinguishing isolated chords is easier than distinguishing choral progressions; but the first three times I read it, I thought it meant the opposite. Why is it so hard to unpack? I think it's because there are three negative-ish words in series here, "harder", "less", and "weird" (and a fourth in parallel, "opposite"). I'm not sure I'd have guessed "harder" and "weird" to be a negative-valence words in this sense, but that's the only way I can explain why I had such trouble understanding the sense of the sentence.

Ben said,

January 26, 2010 @ 6:59 pm

@Steve Harris: Reversing all the words you identified (except for opposite) to positive-valence yields this:

"But the pattern of finding the isolated chords easier than the cadences is more normal than the opposite, obviously."

How does that compare in terms of ease of comprehension?

To me, they are about equal, but it's hard for me to say for sure since I have a-priori knowledge of the sentence's meaning. Nevertheless, I think it may be the word opposite that is actually the most difficult part of the sentence.

[(myl) Thanks for improving my prose! (If there were such a thing as a "sincerity mark", I'd add it here.)]

Dan M. said,

January 27, 2010 @ 4:49 am

This is a very interesting discussion to me, and many of the comments above cover my reactions, but piecewise. I'm one of the ones who has no musical training nor talent but find the two stand-alone cords obviously different while having some trouble telling them apart in the longer sequences. Though interesting, I perceive the second pure note as lower than the first (which is correct), but perceive the second cord as higher than the first, which is inverted. In the longer part, the second is again lower sounding.

I'm with Linda on the matter of enjoying music while having poor absolute pitch perception. While I can't always even tell which of two notes is higher, I have a keen sense of wave form and harmonics. (For instance, I can identify songs I know on the radio by their first note alone.)

I also want to amplify Sili's second comment: I've found discussions of music almost entirely opaque, despite being quite capable of learning vocabulary and understanding the physical phenomena of sound. I think in large part this is a horrible failure of communication between those who find music natural and those who don't (like me). It wasn't until I was in college and asked a friend, who was a mathematician who happened to also sing, that I got even the vaguest inkling what "key" is, and I still have no idea why it matters.

I find the terminology used in music impenetrable, and am consistently annoyed by what appears to be unstated assumptions that are invisible to me. For instance, several commenters here have described one of the two cords as more wrong than the other. What does that even mean? I also infer that "major" and "minor" are somehow evaluative of cords, rather than being arbitrary signifiers as in "positive" and "negative" for charge, as I'd always thought.

(By the way, I find Ben's positive rendering of MYL to be harder to understand in the sense that while I get the same factual meaning, I can't tell what part of it is supposed to impart new information, while the multiply negative form obviously means to emphasize that it's interesting to see data pointing to the unexpected result, but would be uninteresting if the postdoc's work had matched the results in these comments. "More normal" feels insipid to me compared to "less weird".)

Jongseong Park said,

January 27, 2010 @ 7:49 am

My sister and I both learnt to play the piano from a young age, and since then my sister also took up the violin while I took up the guitar. My sister progressed much further than I did on the piano.

Once, in high school, my sister wanted to cover an pop song with her friends; she would be playing the piano. She played the song by ear on the piano. But it was immediately clear to me that she had replaced all the minor chords to major ones (2 minor to 4 major, for example). As the original was an R&B tune, this made a huge difference.

I took out my guitar and transcribed all the chords correctly for her, but she refused to follow it, as she couldn't hear the difference. She ended up performing the song her way. I remember being astonished that someone with her musical training couldn't hear such obvious chord differences.

Aristotle Pagaltzis said,

January 27, 2010 @ 9:20 am

Just for interest, I’ll throw in my data point:

I found both the chords and single notes glaringly different, and have no trouble telling apart the progressions either – although the second one might slip past me if I weren’t paying attention.

Very intriguing finding, thanks for the post.

Robert Royar said,

January 27, 2010 @ 9:51 am

I could hear the difference in all cases. My musical training is limited to a few years of school band and school chorus and a medieval music history course in college. I listen to music of different genres/periods.

I wonder how this experiment could be translated or applied to reading poetry. I was always pretty good at sight-reading poetry and like prose where the author writes with a poetic "voice."

John Cowan said,

January 27, 2010 @ 11:42 am

Dan M.:

"Major" and "minor" are indeed arbitrary signifiers and not at all evaluative. In the context of this discussion, "wrong" simply means "unexpected by the traditional standards of Western music". None of the chords here are "wrong" in isolation, but some sequences of chords are traditional, normal, expected, "right", whereas others are untraditional, abnormal, unexpected, "wrong".

All these chords are consonant; that is, the ratios of the note frequencies are (close to) simple rational numbers like 1/2, 2/3, etc. Dissonant chords also exist, and are likewise untraditional and unexpected, though 20th- and 21st-century classical music makes heavy use of them. In earlier work, however, a dissonant chord was generally a mistake in performance. Hence the remark made by the 20th-century composer Paul Hindemith, conducting an orchestra in a rehearsal of one of his own works: "No, gentlemen, even though it sounds wrong [dissonant], it's still wrong [not what I wrote]".

My own data:

I have been singing informally all my life, and studied piano and music theory intensively for five years as a child. I can sight-sing pretty well, but can't sight-read piano music unless it's quite simple (I always had to decode in advance). My relative pitch sense is excellent down to quarter-tones, and both the simple chord comparisons and the chord progressions are as different as chalk and cheese to me. However, I have no absolute pitch sense at all, and do not know if I am singing (by myself) in C or F#. In this way, if no other, I resemble the late Isaac Asimov, who once at a luncheon meeting sang four verses of "The Star-Spangled Banner" with prose explanations after each verse. Afterwards, a friend told him that he sang the song perfectly, but with each verse in a different key.

Jerry Friedman said,

January 27, 2010 @ 3:51 pm

I had no trouble with the single notes and chords. I couldn't tell the difference in the chord sequences the first time, but then I turned the volume up and listened more carefully, and I could.

I took piano lessons for a few years. I have a poor sense of pitch—in isolation I can tell which of two notes a semitone apart is higher, but in a melody I may hear a semitone down as a semitone up. I have a lot of trouble singing a pitch I hear, and like Linda I'm lost when it comes to comparing pitches with different timbres. (The colors are so different. Okay, when I say that because I have synesthesia , my color-blindness ruined my sense of pitch, I'm joking.)

Isaac Asimov figures in a major-minor story, as I recall from In Memory Now Ripe (maybe). Once when he was sad, he was with a friend for consolation, and somehow Asimov started singing old favorite songs while his friend accompanied him on the piano. But though Asimov was a good amateur singer, somehow there were a lot of wrong notes. Finally his friend figured it out: Asimov was singing even the major-key songs in minor. This probably has less to do with sadness than with Ashkenazic Jewish music.

Claire said,

January 27, 2010 @ 6:13 pm

"there may be a difference between singers or those who play instruments which only produce one note at a time,"..

This sort of test is a pretty standard one for choral auditions, especially for altos and tenors (conductor plays a chord, auditioner has to sing one of the notes). It's definitely a trainable skill although like with most trainable skills, it helps if the person also has some talent for it.

peter said,

January 27, 2010 @ 6:51 pm

John Cowan (January 27, 2010 @ 11:42 am)

"All these chords are consonant; that is, the ratios of the note frequencies are (close to) simple rational numbers like 1/2, 2/3, etc. Dissonant chords also exist, and are likewise untraditional and unexpected, though 20th- and 21st-century classical music makes heavy use of them. In earlier work, however, a dissonant chord was generally a mistake in performance."

Au contraire,, classical composers have long used dissonant chords deliberately, and well before the 20th century. The climax of Mendelssohn's Hebrides Overture (written in 1830) is a 7th chord (on the dominant, F-sharp), containing both the minor-7th and the major-7th as well as the root (ie, all three of E, E-sharp and F-sharp). And the penultimate melody note in Bach's St Matthew Passion (written in 1727) is also a major-7th (against the tonic chord). As the penultimate note, performers often linger on it. There are many other examples.

Matt McIrvin said,

January 27, 2010 @ 7:48 pm

Dan M.: I'm a musical neophyte myself, and while I've had an interest in the physics and psychoacoustics of music for a long time, I also found the terminology of music theory incomprehensible until I started learning to play an instrument (the guitar). That was the key–much of this becomes easier to understand when you approach music from the point of view of making it, rather than just listening to it or even trying to compose it. I'm still not much good at the guitar but I'm using it partly as a vehicle for learning about music itself.

I still find the terminology of intervals a little frustrating because of the proliferation of what programmers call fencepost errors: the ordinal numerical terms for diatonic intervals count starting with 1 (a "third" is two diatonic steps, a "fifth" is four, the "octave" is seven) but other interval terms count from 0 ("semitone", "tritone"). Why couldn't they be consistent?

Well, of course it's centuries of historical accident. There's a lot of that. I'm still trying to figure out exactly why the major scale of natural note letters starts with C rather than A; that's a thousand years old.

cthulhu said,

January 28, 2010 @ 12:42 am

I attend informal jam sessions infrequently, and I'm usually the one going "what's the key?" Once I know that, I can usually follow the chord changes through cadences, including major/minor (I normally play keys, so I move the I &V, and hit III a beat later).

That said, these results do not surprise me at all. People hear different things in music — some people pick out the oboe in a symphony, while others hear the melody even as it is taken up and passed on to different instruments. Still others focus on the rhythmic structure, or the chordal progression.

Cranky-D » Modal Deafness? said,

January 28, 2010 @ 1:03 am

[…] is an interesting article here that states that some people cannot distinguish between a major and minor triad when they are […]

Britt Paty said,

January 28, 2010 @ 1:26 am

I am a musician with a lot of music theory education and a lot of playing and practicing time and I can tell you without a doubt that sometimes it is very hard to actually tell what is going on in any piece of music, especially chord chages and key changes. For me it is very easy to distinguish between the individual chords and also the embedded chords, but when it comes to more complicated music I actually have to sing (in my head) individual notes to fully distinguish the subtle transitions. Here is a little bit of the Dixie Dregs "Divided we Stand". Can you tell whether it is a minor to major transition or major to minor, and if so where in the two bars does the transition happen?

http://www.megafileupload.com/en/file/185927/Major-or-Minor-wav.html

Roger Lustig said,

January 28, 2010 @ 10:34 am

@Matt: The terminology is frustrating because the history of music theory is the history of 2500 years of kludges and trying to reconcile and integrate incompatible systems. Among other things, the terminology was developed over a long time, starting long before zeroes were in common use. The ancient Greek term for a perfect fifth is diapente, so the 5 was there then already.

As to the range of letter-names, a) it doesn't start on C, and b) the "major scale" as we know it wasn't a concept when the letters came into use. The lowest note was "Gamma-Ut", a G (from which we get the word "gamut"), and after that Greek beginning, the Roman letters kick in with A, B, C, etc. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guidonian_hand for that particular schema.

As to the "second" vs. "tone" issue–that stems from medieval theorists' attempts to retrofit what they were hearing and trying to describe onto the Pythagorean notions of tetrachord, mode, etc. Why? Because they had to: everything had to come from Scripture or the ancients in order to be true.

Unruh said,

January 28, 2010 @ 5:52 pm

Re frankly–I think " I was frankly incredulous"., should have been written as

"I was, frankly, incredulous" making it clear it is the same as

"Frankly, I was incredulous" , which means it modifies the whole sentence.

Of course, if there is something called "frankly incredulous", ( as opposed to "deceptively incredulous" I guess, or "shyly incredulous"), then it could modify incredulous.

But that usage of frankly is, frankly, rare. It is hard to imagine it modifying the word "was", although had "depressingly" been used instead, I guess it could have modified "was".

Re the chords, I fall into the group that could hear a clear difference between the individual pair of chords, but the progression was a bit more ambiguous. Not very ambiguous, and it depended on when I played them– sometimes they were very clearly different, and sometimes less clearly. I think the mind sort of mushes that chord as a leading chord, and dismisses it as one dismisses the "the" in a sentence while waiting for the final noun.

It is there to just to delay the final chord, and is mentally ignored. Had it been the final chord in a progression, I suspect what ambiguity there was would have disappeared.

I will certainly use this in a Physics of Music class I teach.

Music Geekery: Other Things Being Unequal « Eric Pazdziora said,

January 30, 2010 @ 5:33 pm

[…] halls. And that leads to a disproportionately fascinating point brought up by Liberman: In an unpublished study, subjects with musical aptitude were played computer-generated musical samples in which the only […]

CarLuva said,

January 31, 2010 @ 4:46 pm

Fascinating. I'm a musician (classical piano and vocal training) with a very good ear; although I don't have perfect pitch, I have near-perfect intonation. For me, discerning the differences in the isolated triads was trivial, but I could conceive of it not being obvious to some people. The difference in the chord progressions was, for me, beyond obvious—it was positively jarring. I cannot imagine how anyone could fail to notice the difference. However, perhaps it was jarring for me because, as a student of music, I immediately recognized it as "wrong" (not technically wrong, of course, but highly non-traditional), from a music theory standpoint.

I subjected my wife, also a pianist, to the test without telling her what was coming. She also easily recognized the difference in all cases, but said that the progression was least clear to her.

John Cowan said,

February 1, 2010 @ 6:48 pm

Peter: Yes, I overstated the case for simplicity's sake.

Rocknerd » Blog Archive » So you think you have good ears. said,

April 9, 2012 @ 7:57 am

[…] you do and think about every day is records and music. So just how closely have you been listening? Can you tell a note out of place in a chord? Lots of testees are surprised and horrified to discover they can't. It took me a few tries, […]