Richard Powers on his way to a decision

« previous post | next post »

A few days ago, Kurt Andersen interviewed the novelist Richard Powers on Studio360. You can listen to the whole nine-minute interview here.

In the middle of the interview, Powers breaks into a sequence of declarative phrases with final rising pitch — what's sometimes called "uptalk". Before and after this sequence, which sets the stage for an account of his decision to become a writer, he consistently uses falling patterns. It seems clear that he means the rising contours to have a rhetorical effect. But it's equally clear that the intended effect is not to signal insecurity or to call into question his commitment to the truth of what he's saying. So as part of my on-going campaign to document uptalk — especially non-stereotypical examples — here's a description.

The preceding passage starts this way, with Powers describing why he left physics:

You- you mentioned the- the- the "two cultures" crisis that uh

that Snow put on everyone's agenda but uh

in fact the crisis really is the "million cultures" crisis and uh

how- however much exhilaration I took out of physics, it w- rapidly became clear to me that uh

even two physicists working in closely related fields couldn't always communicate with each other, and- and for me to make any kind of meaningful contribution

would require

a kind of intense specialization, where year after year I learned more and more about smaller and smaller domains, until I was in-

in danger of knowing everything there was about nothing.

Powers goes on to explain why graduate school in literature was also too confining, and continues to use phrase-final falls. Then comes the story of how he decided to write a novel — and right up to the crucial moment of decision, he mostly ends his phrases with rises:

| Andersen: | So when you decided OK, this is I- I- I'm not gonna be uh a scientist, I'm not going to be uh a literature teacher then you- did you just simply make the decision OK I'm going to write novels and start writing them? |

| Powers: | The books actually started/ on a Saturday morning/ uh in- in uh nineteen eighty one/ I was living in the Fens/ just behind the Fine Arts Museum/ the- the MFA in Boston/ and there was a- a retrospective exhibition of the German photographer August Sander. and I had no prior exposure to this work/ |

| Andersen: | The early 20th century photographer? |

| Powers: | German photographer from the end of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century um and uh I remember going into this first American retrospective/ and turning around the corner and/ seeing this magnificent and haunting photograph, of these three young men in their Sunday best, walking along a muddy road just glancing out over their right shoulder as if suddenly surprised by the photographer. Leaning forward, reading the caption on this photo which read "three– or three young Westerwald farmers on their way to a dance, nineteen fourteen" So of course they were not on their way to the dance that they thought they were on their way to/ and just down the road was world war one. |

| Andersen: | And so you suddenly had your mission. |

| Powers: | I did, I- I looked at that photograph/ I had an almost intact story in mind/ this was a Saturday/ on Monday I went in to- to my data processing job/ and gave my two weeks notice. |

From then on, Powers reverts to falls.

| Andersen: | It sounds as though you had a mission for a career of fiction writing, not just a book. |

| Powers: | ((Well I'm)) I'm not sure it's a mission, I think it's simply the shape that my own temperament takes. |

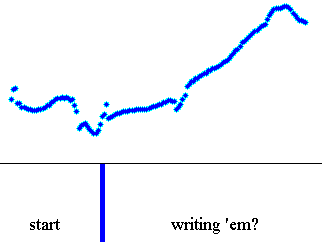

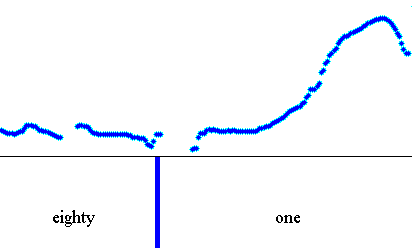

I'm skeptical that there's any systematic difference between the rises often used with yes/no questions, and the rises used for various other reasons, as in Powers' story. As an additional andecdotal piece of evidence in this discussion, here's a comparison (at the scale of time and pitch display) between the end of Andersen's question and the start of Powers' answer:

Andersen: … did you just simply make the decision OK I'm going to write novels and

start writing them/

Powers: The books actually started/

on a Saturday morning/ uh in- in uh nineteen eighty one/

To really address this question in a responsible way, of course, would require comparing the dynamics of a large number of examples of both kinds, paying careful attention to the alignment of the pitch contour with the syllable sequence and with the amplitude contour. But these are among the many examples that make me doubt that there's a systematic difference in such cases (as has sometimes been suggested) between rises that start at the bottom of the speaker's range and rises that start higher.

You'd also want to try some perception experiments.

Here's the picture, "Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance":

Another version of the story is here, in a 2003 interview published in the Paris Review:

INTERVIEWER

When did you begin your writing career?

RICHARD POWERS

In the early eighties, I was living in the Fens in Boston right behind the Museum of Fine Arts. If you got there before noon on Saturdays, you could get into the museum for nothing. One weekend, they were having this exhibition of a German photographer I’d never heard of, who was August Sander. It was the first American retrospective of his work. I have a visceral memory of coming in the doorway, banking to the left, turning up, and seeingthe first picture there. It was called Young Westerwald Farmers on Their Way to a Dance, 1914. I had this palpable sense of recognition, this feeling that I was walking into their gaze, and they’d been waiting seventy years for someone to return the gaze. I went up to the photograph and read the caption and had this instant realization that not only were they not on the way to the dance, but that somehow I had been reading about this moment for the last year and a half. Everything I read seemed to converge onto this act of looking, this birth of the twentieth century—the age of total war, the age of the apotheosis of the machine, the age of mechanical reproduction. That was a Saturday. On Monday I went in to my job and gave two weeks notice and started working on Three Farmers.

Jack said,

October 28, 2009 @ 1:10 pm

I'd be interested to hear your thoughts on what rhetorical effect is being employed, especially since you say, and I agree, that "it's equally clear that the intended effect is not to signal insecurity or to call into question his commitment to the truth of what he's saying."

In the passage regarding the "million cultures," Powers puts audible stress on the words "rapidly," "even," and "closely," – it sounds, to my untrained ear, like a slight rise in register on each word – which seems to therefore stress that the situation had obvious, but counter-intuitive, implications.

However, this is not the same phenomenon which occurs in the main passage in question; instead these instances of final rising pitch don't necessarily imply certain meanings for the listener, as far as I can tell.

Perhaps Powers is using them to create a cadence, so chunks of meaning within the story are delineated. Is this possible? The other thought that occurred to me – purely hypothetical, of course – is that they represent the speaker interrogating himself, but that guess seems colored by pre-existing associations with uptalk.

[(myl) The most obvious answer would be that final rises are often used to draw the listener in and invite or even compel attention. In this passage, Powers uses rises on the phrases that draw the listener into the process that climaxes with his "visceral" confrontation with the three farmers' gaze, and then again into the process that lead up to quitting his job and starting to write. Going well beyond the evidence, we could say that in each of those sequences, there's a sort of rhetorical arsis/thesis or tension/relaxation, and the rises are associated with the rising part of that rhetorical arc, while the return to final falls align with the return to the rhetorical ground state (and, of course, the release of a quantum of metaphorical energy).

If we had a larger sample of Powers' oral storytelling, we might find some evidence that he uses rises this way more generally. But other people certainly do; and I find this way of thinking about it more convincing than the idea that he's asking himself (or anyone else) a series of questions.]

Nathan Myers said,

October 28, 2009 @ 1:48 pm

Maybe somebody could ask him. Is he in the book?

[(myl) Most people aren't aware of their prosodic choices, any more than they're aware of the choices that they make in performing other skilled and complex actions; and to the extent that they know what they did, their explanation of why they did it in one way rather than another are usually post-hoc rationalizations rather than insights into the process with any predictive (or retrodictive) value.]

Skullturf Q. Beavispants said,

October 28, 2009 @ 3:41 pm

@Nathan Myers at 1:48 pm:

To steal an example from Douglas Hofstadter, maybe it's not all that different from asking somebody "Why are you making so many white blood cells today?"

Nathan Myers said,

October 28, 2009 @ 4:14 pm

I'm aware that we often don't know why (or even that) we're making prosodic choices. Sometimes, though, we are, and sometimes it's a deliberate choice. This seems particularly likely for the case of a professional storyteller.

If we don't trust Powers's account, we might get some insightful suggestions from other professional speakers who have strong motivations to understand the consequences of their vocal activity. I speak, of course, of comedians. Does anyone maintain correspondence with, e.g., Mr. Fry?

Bloix said,

October 28, 2009 @ 9:20 pm

I believe what we are hearing in the uptalk is Powers recollection of the moment, as he re-experiences the power of his first confrontation with the photograph. He is tentative and even vulnerable, as if he is not sure that his auditors will understand or empathize with what he is trying to say – after all, he is recounting how an obscure work of art altered the course of his life – and at the same time he is not wholly in control because he is very slightly in the grip of that past moment. Hence the uncertainty that is expressed in the uptalk. Obviously he has told this story before, so there may be a bit of a rehearsed quality to it, but my sense is that the emotion is still genuine enough.

But then I dearly love that photograph and have ever since I first saw it in John Berger's book, About Looking. Sander was an extraordinary genius and I don't doubt the power of his work to change a life.

Rob said,

October 29, 2009 @ 3:53 am

Surely if this is a relatively common phenomenon then a listener will be able to provide as good – if not better – information about what rhetorical effect he is attempting. I mean, as a listener I can distinguish between "This is yours?" and "This is yours." The test would have to be a little more sophisticated than this, but it would be possible.

Unfortunately, with my sample of one I can't offer much help, as I've never heard it used in this way before. In Australian English (especially among teen girls in the 80s), the uplift finished almost every phrase apparently regardless of context. It was interpreted by amateur linguists at the time as saying, "I'm not finished yet." It would be interesting to see if the interviewer ever interrupts the story after an uplift. Either way an uplift from an educated American male sounded very odd to me.

Here's the best example I could find. Unfortunately it's a parody: Kylie Mole on Youtube

Linklog: Checkout autobiographers, the tone of Richard Powers, and more said,

March 12, 2011 @ 8:25 am

[…] • The music of Richard Powers coming to a decision. […]