Sorites in the comics

« previous post | next post »

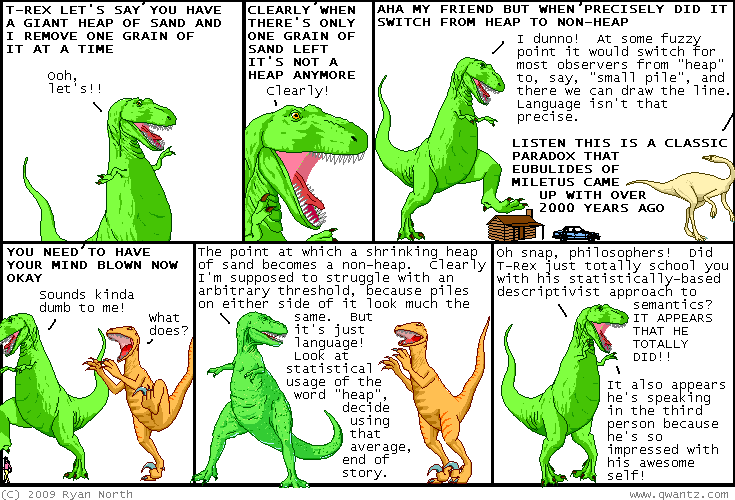

Today's Dinosaur Comics disposes of the sorites paradox:

August 29, 2009 @ 12:17 am · Filed by Mark Liberman under Linguistics in the comics

« previous post | next post »

Today's Dinosaur Comics disposes of the sorites paradox:

(Click image for a larger version.)

August 29, 2009 @ 12:17 am · Filed by Mark Liberman under Linguistics in the comics

Powered By WordPress

dr pepper said,

August 29, 2009 @ 12:25 am

That's also the answer to creationists, who get desperately confused over when a species changes.

Bill Muir said,

August 29, 2009 @ 1:37 am

Please Mr. Pepper, there's nothing that need be inflammatory about this. Just appreciate some cleverness for its own sake and bask in the glory of having understood some of what might well have been intended for us to understand.

Mike Keesey said,

August 29, 2009 @ 2:10 am

Actually, I thought it was a pretty good analogy.

Lee Morgan said,

August 29, 2009 @ 2:22 am

I prefer a fuzzy logic solution, but this is also somewhat reasonable.

Nat said,

August 29, 2009 @ 4:15 am

It's not a solution. At least not yet. T's answer is to take the average of everyone else's answer. At least the way he's formulated it, he's presupposing that each individual will have a specific cut-off point. It's these points which he proposes one should average over. This means that in order for T to give his answer, everyone else has to answer first. He's simply compounded the problem.

I can see some possible modifications he might make that would look more like a solution. But I'm not going to do his work for him.

His ethics, on the other hand, are impeccable:

http://www.qwantz.com/index.php?comic=599

Graeme said,

August 29, 2009 @ 4:58 am

So that's why they fell extinct. Too much linguistic debate.

Yuval said,

August 29, 2009 @ 5:14 am

Yes, but, but… he was speaking in the SECOND person, not the third!

Stephen Jones said,

August 29, 2009 @ 6:25 am

A very perceptive comment by dr pepper.

Harlow Wilcox said,

August 29, 2009 @ 7:50 am

Is it just me, or did the entry "New Scientist rips off Language Log; we don't care" disappear even as I was reading it? I clicked-through a link, and when I came back, the whole thing had gone missing. Apparently, when New Scientist rips off the Language Log, it isn't metaphorical; they actually carry off entire articles.

Sili said,

August 29, 2009 @ 8:19 am

Thanks, Harlow. I thought it was just me, imagining things.

MattF said,

August 29, 2009 @ 9:11 am

There's a case of this problem that isn't so easily dismissed– Specifically, is there a concrete definition of 'typical' or 'random'? I don't see any way of defining these terms in an unambiguous way, unless you draw instances from an infinite ensemble. On the other hand, in real life, there aren't any infinite anythings. So, there's a problem, IMO.

Mark F. said,

August 29, 2009 @ 9:57 am

The actual solution to the problem is in the upper right panel. By the time T-Rex comes up with the statistical approach he's already getting too fancy.

Emily said,

August 29, 2009 @ 10:28 am

I think what's presented in the top right panel may qualify as a fuzzy logic solution– it does mention a "fuzzy point".

John Lawler said,

August 29, 2009 @ 11:48 am

Note that the URL for this post is p=1700.

Then note that the post on Google Books that you get to

by pushing "Previous Post" is p=1698.

Quod erat demonstrandum.

peter said,

August 29, 2009 @ 11:57 am

And occasional comments, too, seem to appear and then disappear. I recall that the third commentator on Geoff Pullum's post "Failing Immediately To" was critical of Prof. Pullum's editing policy. But that comment too now seems to have disappeared.

I hope these are technical snafus, and not evidence of trouble at mill down at Language Log Plaza.

Craig Russell said,

August 29, 2009 @ 12:19 pm

I took his "statistical" suggestion to mean taking some huge corpus of speech, finding every example of the word "heap", seeking out (somehow) the physical object that was being referred to in every instance where that's possible, and using that data to determine the limits of sizes of piles that are typically described as heaps. Did others assume he meant directly asking a bunch of people how small something could be and still count as a heap, and then averaging the sizes? That seems much less useful and meaningful (although admittedly my method would only work in theory; it's hard to imagine a situation where it could actually be carried out.)

mgh said,

August 29, 2009 @ 2:35 pm

does everyone really take the difference between "heap" and "pile" to be size?

to me, the same set of clothes could be in a pile (orderly) or a heap (disorderly) — it's more a difference of geometry than number!

(obviously, bigger aggregates of things tend to look more disorderly, but for example the salt piles in Vancouver are enormous but orderly, therefore "piles" not "heaps"!)

jack said,

August 29, 2009 @ 3:00 pm

There is a solution in this: the point at which an observer no longer describes the sand as a heap. Adding the nonsense about "statistical usage of the word heap" confuses the issue, because it then seems to take on a semi-objective quality, derived from multiple subjective judgments, which implies we could arrive at a precise number (the average of the points at which each observer changed their assessment from "heap" to "not-heap").

The problem seems to me to be the implicit argument in the original paradox that the system of understanding in which heap exists can be directly correlated to a quantitative system of understanding. But this is not the case. Heap is a descriptive word, implying certain physical characteristics of an agglomeration, and only has a vague quantitative correlation, which to my mind is >2, although, arguably, could be only >1. However, the state of the agglomeration, while dependent upon there being multiple objects, also depends upon a specific physical arrangement of those objects. To imply as the original paradox does that "heapness" depends only upon quantity occludes the descriptive portion of the meaning of the word, thus generating the paradox. At some point in the removal of grains of sand, the relatively precise description of the word "heap" will cease to be valid, and there is no direct correlation between when this change takes place and the number of grains of sand present in the agglomeration, only a lower limit.

Tarlach said,

August 29, 2009 @ 3:23 pm

There's no paradox. No one removes a grain of sand at a time from a heap of sand so this never matters. It's only interesting if you treat language like some exotic thing that mere mortals use, in other words, to autistic nerds.

Tarlach said,

August 29, 2009 @ 3:24 pm

But the comic itself was clever and cute.

Nat said,

August 29, 2009 @ 3:58 pm

Mark, Emiliy,

whether or not he has a solution depends on what he means by a "fuzzy point". He immediately follows this phrase by proposing that one draw a line at this point. So, T doesn't seem to have a coherent proposal in mind. There seem to be at least three different ideas represented. (1) Fuzziness of the concept of "heap". (2) Arbitrariness of a cut-off point. (3) Statistical determination of meaning. T moves from (1) to (2) to (3), but (2) really isn't compatible with either of the other ideas. Fuzziness means there is no cut-off point. So, it's wrong to say that it's arbitrary. Arbitrariness means that there is no correct determination, so it's wrong to say that a statistical answer will be correct. One could use the statistical method as a way of choosing an arbitrary point. But if it's truly arbitrary then there's no sense in which the statistical method is the correct one.

Craig, you could do that. But if all you want is some empirical sample of application of "heap", you might just as well present T with a series of piles and ask him to categorize each one as a heap or a non-heap. You could take an average or you could just get someone to pick a number that coheres with his or her usage. However, either way, I think there's something important lost by this approach. There's a range of cases in which judgements will be less secure and more uncertain. People will say things like, "It's kind of a heap, but kind of not". I take it that the "fuzziness" answer wants to capture this.

One way of phrasing paradoxes, which I think is quite good, is to present a small set of intuitively correct sentences which are jointly inconsistent. For Sorites these could be:

A. A pile of 500 grains of sand is a heap.

B. A single grain of sand is not a heap.

C. Removing one grain of sand from a heap cannot turn it into a non-heap.

The statistical solution denies C. Fine, but then we do need an explanation of why C is is prima facie correct. I take it that fuzzy logic can do something like this, but that T-rex doesn't see anything compelling about C. I think this is a mistake. (Notice that the cartoon presents A and B, but not C. Instead, it asks what the cut-off point is, thereby assuming that C is false).

jack said,

August 29, 2009 @ 4:13 pm

There is a solution in this: the point at which an observer no longer describes the sand as a heap. Discussing the statistical usage of the word heap confuses the issue, because it then seems to take on a semi-objective quality, derived from multiple subjective judgments, which implies we could arrive at a precise number (the average of the points at which each observer changed their assessment from "heap" to "not-heap").

The problem seems to me to be the implicit argument in the original paradox that the system of understanding in which the word heap exists can be directly correlated to a quantitative system of understanding. But this is not the case. Heap is a descriptive word, implying certain physical characteristics of an agglomeration, and only has a vague quantitative correlation, which to my mind is >2, although, arguably, could be only >1. However, the state of the agglomeration, while dependent upon there being multiple objects, also depends upon a specific physical arrangement of those objects. To imply as the original paradox does that "heapness" depends only upon quantity occludes the descriptive portion of the meaning of the word, thus generating the paradox. At some point in the removal of grains of sand, the relatively precise description of the word "heap" will cease to be valid, and there is no direct correlation between when this change takes place and the number of grains of sand present in the agglomeration, only a lower limit.

Simon Cauchi said,

August 29, 2009 @ 5:20 pm

It's not only post 1699 that's gone missing. What's happened to no. 1691 — and what was it anyway? Likewise 1685? (These are rhetorical questions. I don't actually want to know.)

Emily said,

August 29, 2009 @ 5:20 pm

@Tarlach:

No one removes a grain of sand at a time from a heap of sand so this never matters.

It matters, apparently, to philosophers. As do issues like whether someone would refer to "undetached rabbit parts". But you have a point– it takes a philosopher to even think of thinking about such matters in the first place, because nobody does.

@Nat: Good (non-fuzzy) point. I'm not sure what "fuzzy point" even means– the whole notion seems oxymoronic.

jack said,

August 29, 2009 @ 6:44 pm

whoops, sorry for the double post. for some reason my first comment took a while to show up.

Marinus said,

August 29, 2009 @ 9:41 pm

The reason it matters to philosophers isn't because of any interest in piles of sand, but because you can create a sorites paradox for any vague term in the language: being bald is another standard example, as is the boundaries between colours. As pepper said straight away, speciation is an example as well. A pile (or heap, or mound, or whatever) of sand is just a nice way to illustrate the problem, because there are insignificant changes you can make to some X to eventually change it to a non-X. Seeing how to do it with grains of sand makes it easier to see it done with hairs on the head, small changes in the wavelength of visible light, etc. If there is an uncertainty about how words refer, then it's hard to pin down the truth conditions for statements, etc, in a way which especially troubles scientific theory. Bertrand Russell for one simply though it was impossible to have a properly-so-called mathematical or scientific theory with any vague terms in it.

All you're likely to discover with a statistical analysis is how people do use vague terms, but that isn't a solution to the problem of vagueness. Everybody knows that we speak of heaps and non-heaps of sand, bald and non-bald people, blue and green, and so on. Philosophy is often concerned with different issues than linguistics, though: in the philosophy of language, the question is more often how words refer than what they refer to. There is a way to use statistical analysis give informative answers to the question of how words, like vague terms, refer: if the meanings of words just were the way they were used. Ludwig Wittgenstein famously held this view. However, it isn't obviously correct, and it's not even one of the most popular candidates. There are a few problems with this view: the one that impresses me most is that we sometimes take people to rightly use a word in some way and sometimes not, which means that there are correctness conditions on the use of a word. But if there are such conditions, then it isn't just how a word is used that determines what it means. You can try to get from a statistical analysis to correctness conditions (it's correct to use the word the way most people do), but actually doing so has turned out to be very difficult. And without knowing what the correct application of words are, it's hard to be suitably precise with those words in the types of situations where that matters: scientific theories, but also legal matters, and a few other things.

Nathan Myers said,

August 29, 2009 @ 9:52 pm

I first encountered this, in my teens, as "the fallacy of the beard". Does one whisker qualify as a beard? Two? Etc. My conclusion was that language is not compatible with logic, and there it has stood.

Nothing is better than a mozzarella and tomato sandwich, yet a mozzarella and tomato sandwich is certainly better than nothing.

mlandis said,

August 30, 2009 @ 1:40 am

A statistically-determined mean from the responses from any significantly sized sample is unlikely to yield a discrete value. What shall we do when we discover a heap loses its status when it lessens from 17.42 to 17.39 grains of sand? Would anyone who participated in the survey even agree with the mean values? Naw.

Simply because we calculate this linguistic mean also doesn't mean it defines the data set. The mean describes a characteristic of the data set. If we have a truckload of Golden Delicious and Macintosh apples, it would be erroneous to describe them as the color orange (that is, the qualitative mean; the quantitative mean may be ~630nm frequency light (red-orange)).

Most importantly, never criticize a dinosaur's logic. A T. Rex will eat your pedantic ass right up.

mlandis said,

August 30, 2009 @ 1:42 am

Oops — meant whole number, not discrete value. But I'm sure you get the point.

peter said,

August 30, 2009 @ 2:53 am

Emily said:

"It matters, apparently, to philosophers."

And pretty much anything that matters to philosophers eventually matters to computer scientists. If you want to build automated reasoning systems as subtle as human decision-makers, then paradoxes such as Sorites have to be confronted.

Marinus said,

August 30, 2009 @ 6:53 am

Nathan said: "My conclusion was that language is not compatible with logic, and there it has stood."

This could be a relief, if we had anything other than languages to do logic in.

The problem of vagueness is a problem of reference: when does something count as an example of a heap/being bald/green/a different species/some other vague category, and when not? Since all logics must ultimately refer to something, even if it is something as abstract as a lattice of variables, they are languages in that respect at least, even if they are very formal or unusual ones. And if that language makes use of any vague terms whatsoever, you can construct a sorites paradox in it. The usual response is to try and strip all vague terms out, though there are people who wonder whether this is possible at all.

Marinus said,

August 30, 2009 @ 7:04 am

It's worth mentioning what are currently the most popular candidates for solving the sorites paradox:

Firstly, there is the 'epistemic' approach, which says that there is some sharp cut-off point between where a vague term applies and where it doesn't, it's just that we don't know what it is. It makes good sense of our usual logic, and, in my view, no sense at all otherwise. T-Rex seems to old this view, with a statistical analysis being how you discover what the cut-off point is. T-Rex is almost certainly wrong (luckily, I'm well outside of his reach when I say this).

Secondly, there is the 'degrees of truth' approach, which says that truth isn't discrete, but a continuous range, so you can have 'this is blue' true to .75, and so on. This is the epistemic approach in fancy dress, with extra problems: what counts as true to degree 1, how are the degrees calibrated, what is the cut-off point where a vague term stops to apply, and a few other things that are just mysterious.

Thirdly, there is the 'vague objects' approach, which says that vague terms work the way they should, because the world itself has fuzzy borders. A mountain is a typical example: there seems to be no fact of the matter of where a mountain starts and ends. Most people simply refuse to believe that this is the case, though.

Anyway, the sorites paradox has remained a topic of debate for over two thousand years because it is very, very hard to avoid, and because there are a variety of possible approaches which are mutually exclusive, with reasons to believe them and reasons not to. It's a paradigmatic example of a philosophic problem in that regard.

Pekka K. said,

August 30, 2009 @ 8:59 am

Perhaps we should consult the Bedouin. I've heard they have over 100 words for different sizes and shapes of heaps of sand. (Pekka would like to apologize in the third person for this comment. He couldn't resist.)

Mark F. said,

August 30, 2009 @ 10:41 pm

Incidentally, my son used to ask me questions like "What's the smallest mountain in the world?" which led to some interesting conversations.

dr pepper said,

August 30, 2009 @ 11:13 pm

How surreal it would be to live in a world where platonic archetypes were immediately apparent to observers.

Maureen said,

August 30, 2009 @ 11:16 pm

You can't heap sand. It doesn't come in heaps.

Nanani said,

August 31, 2009 @ 12:46 am

@ Mark F.

Don't know about the world, but the smallest mountain in Japan is Mount Tempo: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Tenp%C5%8D

:)

sleepnothavingness said,

August 31, 2009 @ 7:36 am

Surely the minimum number of grains required to form a heap (or a pile) in the correct geometry would be three. From two grains one might merely be able to form a stack.

acilius said,

August 31, 2009 @ 8:37 am

@Marinus: Thanks for your comments! I for one think you've done a very good job of explaining why this issue keeps nagging at philosophers.

Chris said,

August 31, 2009 @ 9:33 am

IMO, no set of sand grains either "is" or "isn't" a heap – we choose to call it a heap or to not call it a heap. Sand grains are in the universe, the concept of "heap" is in our heads. Similar remarks apply to baldness, beards, bluish green, and speciation. T-Rex's approach is not bad – at least he seems to recognize that differences of opinion shouldn't be resolved by some kind of prescriptivism – but even then, he seems to impose a veneer of defined correctness on the statistical result which is IMO unjustified.

The problem of vagueness is in our own heads, because the categories to which it applies are also in our own heads.

Jorge said,

August 31, 2009 @ 10:48 am

"Sand grains are in the universe, the concept of "heap" is in our heads."

Then what's the minimum number of atoms you need in order to have a sand grain?

Marinus said,

September 1, 2009 @ 1:04 am

The problem of vagueness might be in our heads, but language is a way to relate things in our heads to the world and to each other, so that's hardly a relief. Uncertainty at either the inside of our head, or what we refer to, or how the practice of referring itself works can undermine our attempts to communicate, so the problem remains.

Terry Collmann said,

September 2, 2009 @ 12:32 pm

After I read all this I collapsed in a heap.

The world IS fuzzy, right down at quantum level – get over it, philosophers.

Duncan said,

September 2, 2009 @ 6:53 pm

While I ought to moderate the tone somewhat (but I won't because I'm lazy and largely anonymous anyway) I actually happened to have written a rant to a friend about this comic the other day (from an irate philosopher's perspective). The passages suggesting that Tim Williamson and his ilk are an embarrassment to the philosophical tradition have been excised from the original in the interests of taste and conviviality.

"The only appropriate response would be 'if everyone jumped off a cliff

would you jump off too?' Even you could find an average number of grains

which prompts the switch to using 'heap' for a significant percentage of

the population (a) that doesn't guarantee that any individual uses that

number to make the determination, so you would be saying that everyone

using the word is wrong, (b) people are not consistent in their use of

vague terms such as 'heap' or 'bald' (the classic examples) anyway, so

you'd get a different result each time you repeated the experiment, (c)

even if the statistical majority did use it in a particular way, it seems a non

sequitur to then say to people who use it some other way that they ought

to use it in this way as well (which is what you'd be saying if you said

that was the correct way to use the term), particularly as this seems to

undercut the presumption of your method which is that there are no

rule-based criteria on which to make the judgment, (d) this completely

misrepresents the actual psychology of the usage of the term, as even if

you could show e.g. 'less than 1677 hairs makes a person have applied to

them the term 'bald' on average' you can be positive that no one using

the term is counting the hairs and, if there is less than '1677' using

'bald'; human beings do not use vague terms according to these kinds of

strict rules and as such both the conclusion misrepresents what is

actually going on in the head of the person using the term, but also

cannot be prescribed to the population as I cannot comfortably adapt

my usage to your rule.

However it's not actually the stupidest 'solution' to the sorities paradox

I've heard. The current Wykeham Professor of Logic…"

@Terry Collmann: Don't be absurd. That isn't the point. Sure, perhaps the world itself is 'fuzzy' (a belief, incidentally, which I share with you but for different reasons than you appear to have for holding it) some terms are fuzzier than others. There are reasonably reliable rules you can identify groups of people using, even if Quine and Wittgenstein have shown that, logically speaking, sooner or later your rules become impossible to resolve with behaviour. "Dog" is a less vague term than "bald". If I ask a man in the street "how do you know when something is a table" I dare say he'll be able to make a stab at it. I don't know, but I imagine someone who works in graphic design does know, when a shade stops being 'pink' and starts being 'puice'. But no one, other than the obviously mad, has any clear idea when someone starts being bald and stops being hairsuite. It's just one of those things that you 'know it when you see it'. But all terms can't be like that. Science would collapse if we had people saying "well, I can't give you a formal definition of what makes something a fish; I just know it when I see it".

@'Dr Pepper' – Actually if you put down Richard's 'God Delusion' and read some of his other books you'd know that biologists aren't entirely sure what constitutes a species either. The textbook definition is a group of organisms which can successfully interbreed (that is; the offspring they produce are fertile – horses and donkeys can produce mules but the mules cannot produce anything), but there are tricky logical problems which come with this definition; there is a kind of bird (the species, ironically, escapes me) which has varieties all round the north pole. Each variety can interbreed successfully with its neighbours on either side, but when the ring is completed (i.e. the descendents of the birds who went 'west' finally made it back round to the 'east') they are no longer able to interbreed with the similar birds found there. Is this a species? It's not clear we need an answer to it, but the point is that (to go philosopher for a moment) that 'able to successfully interbreed' is a symmetric and (technically) a reflexive relation but it isn't a transitive relation as these birds show, and if you want your definition of the 'species' relationship to be an equivalence relation, that's sort of a problem. So it's not just creationists who are puzzled by 'species'.

@Marinus – Nothing to add, save that I vote for option 4: vague terms don't have a fixed semantics at all; all language is intersubjective and we just muddle through in the hopes that our behaviour as regards such oddities as vague terms is close enough that it doesn't cause any major problems. To insist that every term has an exact and universal definition to be found, if only we scratch our heads long enough, is really just an analytical fetish worth getting over.

Kevin Lawrence said,

September 2, 2009 @ 7:38 pm

Herring Gull/ Black-headed Gull.

The standard definition also tricky for species that reproduce asexually.

Loy14 said,

October 22, 2009 @ 10:51 am

A paradox of the current media moment is that, while journalism jobs are disappearing, j-school enrollment is up? ,