A Tale of a Pot

« previous post | next post »

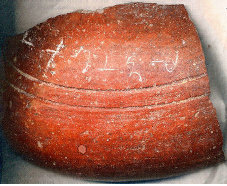

A few days ago an unusual article appeared in The Hindu. It is about the fragment of a pot shown above, a pot used for collecting toddy (palm sap, modern Tamil கள்ளு) made about 1800 years ago. The writing on the pot is in Tamil Brahmi, a writing system that only fairly recently has come to be well understood. It says: n̪a:kan uɾal, Old Tamil for "Naakan's (pot with) toddy-sap". In modern Tamil writing this would be: நாகன் உறல். As the article points out, the fact that a poor toddy-tapper would write his name on a pot is indicative of mass literacy at the time.

The article is interesting to me in part just because of the photograph. I've seen photographs of Tamil Brahmi texts before, but never in color, and having never been to India, I've never seen such a text in person. The other interesting thing about the article is the authorship. Newspaper articles are usually written by reporters. As we not infrequently note here on Language Log, there are a few good ones, but all too often they get things wrong. Well, this article is not by reporters; it is right from the horse's mouth. The authors are S. Rajagopal, retired senior archaeologist with the Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology and Iravatham Mahadevan, an eminent student of early Indian writing and leading authority on Tamil Brahmi, author of the Early Tamil Epigraphy volume in the Harvard Oriental Series, which belongs on every shelf. This is like having a newspaper article on physics written by Stephen Hawking. I hope it's the beginning of a trend.

John Cowan said,

May 18, 2008 @ 1:45 pm

I'm not so sure about the mass literacy: if the toddy-tapper was worried about having his pot stolen, he might have paid a scribe to write the inscription.

David Eddyshaw said,

May 18, 2008 @ 1:48 pm

On the other hand, there's not much point in writing your name on your pot unless there are plenty of people about who can read it.

marie-lucie said,

May 18, 2008 @ 2:35 pm

This reminds me of the inscribed pots of European antiquity, specifically those used among "barbarian" people. There are two kinds: some of them, usually made of metal, bear the name of the maker (and not necessarily that of the recipient), but a number of them, made of coarser material, often bear the name of the owner and/or a suitable inscription praising the beverage in the pot, or even the serving-girl who will fill the pot for the consumer. In France a number of pots of the second kind have been discovered in recent decades, bearing inscriptions in Gaulish which are valuable records of that poorly attested language. I imagine that those pots were made for use in a social setting, such as a taberna where customers would bring their own pots to be filled for consumption on the spot ("bring your own mug"), among other customers whose locally made pots would probably be identical except for the inscriptions. Perhaps the Tamil pot was used in similar circumstances? It seems unlikely that this pot was the only one of its kind, even if only one has been found.

Bill Poser said,

May 18, 2008 @ 4:01 pm

I'm not sure if things worked the same way in the 3d century, but as I understand it, the way toddy-tapping is generally organized today, the tappers bring the sap that they have collected to the toddy-shop, where it is allowed to ferment and sold. Marking one's own pot might therefore be a way of distinguishing it from those of other tappers bringing in toddy around the same time. The tapping itself is pretty much a solitary business .

There's an interesting blog post here about modern toddy-tapping in Kerala, as you can tell from the third photo, which has kallu, the modern word for toddy in both Tamil and Malayalam, written in Malayalam script.

Bill Poser said,

May 18, 2008 @ 4:09 pm

As to whether the inscription was written by Naakan himself or by a professional scribe, I think he wrote it himself. The reason is that I think that there are errors of the sort that people who do not do a lot of writing are prone to make. However, I am not sufficiently expert in Tamil Brahmi epigraphy to say this with much confidence.

Ambarish said,

May 19, 2008 @ 12:15 am

To a native Tamil speaker like me, this is fascinating stuff!

Did you mean "நாகன் உறல்" rather than "னாகந் உறல்"? The former is modern Tamil writing for "nākaṉ uṟal". Or is this one of the errors you mention in your comment?

Bill Poser said,

May 19, 2008 @ 1:07 am

Ambarish,

You're right, I've fixed it in the post. I swapped the first and last "n"s. Being very far from a native speaker of Tamil, I get them confused. Interestingly, the same name occurs with an initial retroflex nasal (modern ண) in an inscription on a stone bed in a cave at Pugalur (No. 72 in Mahadevan's book), which Mahadevan attributes to influence from Prakrit.

Ambarish said,

May 19, 2008 @ 3:25 am

Thanks, Bill. I haven't read Mahadevan's book, but I think I must. In the meantime, I find it interesting that he attributes the initial retroflex to Prakrit. First, initial retroflex plosives are verboten in Tamil, and I was under the impression they don't exist in Sanskrit either, other than in borrowed words. The other curiosity is the theory I've heard (not sure if it's accepted wisdom) that retroflex consonants were borrowed into Indo-Aryan languages from Dravidian languages, which explains why they don't exist in, say, Latin.

Anyway, I'm sure I'll have answers when I actually read the book.

Bill Poser said,

May 19, 2008 @ 4:47 am

Ambarish,

While it is true that the retroflexes of Sanskrit are attributed to Dravidian influence, by the time this pot was made Indo-European languages had been spoken in India for well over a thousand years and the retroflexes had long since become native. Many retroflex consonants in Sanskrit have no Dravidian source, e.g. those that arise via the ruki rule.

mollymooly said,

May 19, 2008 @ 8:25 am

I would love to see a pot (Gaulish or Old Tamil) inscribed "world's greatest dad"

Doc Rock said,

May 19, 2008 @ 9:44 am

As Aristotle is said to have said, "One swallow does not make a summer, neither does one fine day; similarly one day or brief time of happiness does not make a person entirely happy."

Nor does one pot prove a broadly literate society. There are many possible alternative explanations other than the one inference drawn by the scholars in question. If there were several similar survivals with of common tools, etc., with inscriptions of such type, the inference might be viewed as more than idle speculation or ethnic pride.

In societies dominated by a scribal group which derives its power from its literacy, for example, writing can take an a magical aspect and having one's name inscribed upon one's property might have been desired as a powerful charm. Many other scenarios are possible.

Sandhya Sundaresan said,

May 19, 2008 @ 12:25 pm

Hi Bill,

Really interesting post! I'm glad the Hindu thought fit to publish this.

A couple points though.

1. 'toddy' is actually standardly spelled கள், not கள்ளு, though it is still pronounced கள்ளு. This is because of the diglossia, of course – in the formal version which is also the written one, the word is கள், not கள்ளு. People thankfully seem to care less and less about this distinction, but prescriptivists (like my mom!) still give me trouble for not writing the 'proper' Tamil spelling on occasion.

2. It's also interesting that the pot says நாகன் உறல், with zero-marking on நாகன். In modern Tamil, I would actually write this as: நாகனின் உறல் or நாகனுடைய உறல், (and speak a version of the latter) with genitive/possessive marking on நாகன். This is independent of the diglossia issue – though you can often leave out the genitive marking in such cases (as with possessive pronouns, for example), it sounds a bit odd to do that here because the meaning you get is of a compound-word (like: 'naagan-pot' instead of 'Naagan's pot'). Interesting.

Bill Poser said,

May 19, 2008 @ 12:26 pm

Doc Roc,

You're quite right that a single inscribed pot does not prove widespread literacy. That's why I said that this pot is "indicative" of widespread literacy. Actually, there are hundred of potsherds with Tamil Brahmi writing. In making the argument for widespread literacy, Mahadevan (pp. 160-161) points out that these inscribed potsherds are found not only in major urban centers but in obscure hamlets, that they are secular in character (in contrast to most of the rock inscriptions, which are Jaina or Buddhist), and that the names occurring on them indicate that people of a wide variety of classes and occupations owned them.

language hat said,

May 19, 2008 @ 12:26 pm

Doc: While of course the pot does not "prove" a literate society, it's a valuable indication. We'll never know for sure (unless we turn up a daily newspaper from the period), but surely the literacy scenario is more likely than the magical-charm one.

John Cowan said,

May 19, 2008 @ 2:12 pm

David Eddyshaw: It's not required that lots of people can read the pot, just that people in authority can do so. It's not necessary that lots of people know where the VIN (vehicle identification number) on a U.S. car is, just that enough people know so that it can be entered into evidence if there is a crime or dispute about the identity of a car. Similarly, the social benefits of DNA evidence don't require that we all be equipped with DNA labs in our homes.

Bill Poser: Even little villages in India in the 19th century, before anything approaching mass literacy, had their scribes.

john riemann soong said,

May 19, 2008 @ 3:06 pm

Hmm, but would that be a cause to mark for the toddy sap? I wonder if the legal authorities would have needed to know that the pot bore toddy, just who owned it. Whereas, it seems useful if there had been a danger of someone using it for something else than toddy sap — another literate worker, or family member, for instance.

Also if the writing were indeed analogous to a vehicle registration number, I wonder why only one personal name was used (no patronyms?).

dr pepper said,

May 19, 2008 @ 4:15 pm

IANALinguist but the magical charm explanation makes sense to me. If we assume that people who are less than fully literate would at least learn to write their own names,and they know someone else who has marked their own property, they could make do by putting their name on the item, and copying the rest from the other person's. It would be interesting to see if simple errors are propogated in a community.

As for gallic literacy, is that general or concentrated along the mediterranean coast?

Doc Rock said,

May 19, 2008 @ 6:30 pm

Thanks to Bill Poser and languagehat for the useful clarifications–I agree that the widespread existence of analogues, indeed, may be supportive of the widespread literacy hypothesis. Upon reflection, also, the early and abundant Indus Valley seals from Mohenjodaro, etc., seem to support widespread proliferation of "letters" on the Indian sub-continent and tangential areas from these very early times–whether, however, they were, on the other hand, readily and broadly apprehended by the average laborer or toddy collector requires some further substantial evidence I would think.

David Marjanović said,

May 19, 2008 @ 7:39 pm

There's a tin plate from Berne…

goofy said,

May 20, 2008 @ 3:13 pm

I see uṟal, but I don't see how the first 3 characters spell nākaṉ.

Geoff Nathan said,

May 20, 2008 @ 7:04 pm

I know it's 1500 years later, and in another country (and besides.. well, besides…..)

Anyway, I've always been struck by the fact that Shakespeare simply assumes that Nick Bottom, Peter Quince and the rest, all simple workmen, apparently find no problem reading a script (well, except one of them who mispronounces 'Ninus'). Widespread literacy at the lower socioeconomic level didn't seem to be any kind of deal in the late fifteen hundreds (regardless of when the play was supposed to be set).

john riemann soong said,

May 21, 2008 @ 4:17 am

Is it possible to have been labelled illiterate if you didn't know how to read Latin, as opposed to that vulgar pedestrian language that was your native tongue?

marie-lucie said,

May 21, 2008 @ 5:56 pm

At that time, "grammar schools" were not to teach English grammar (which was not taught) but Latin. I guess that a lot of people learned to read from each other, at home or on the job, if they needed it. As for writing, spelling was not something the average person had to worry too much about.

About literacy in Gaulish: Gaulish was not written until the arrival of Greek colonists first, then the Roman conquerors. Obviously those Gauls who learned to read and write Greek or Latin could take advantage of their new skill to write in Gaulish the same kinds of things of personal interest they saw written by the newcomers, such as tombstones (some of them bilingual) and various personal objects, especially those that were easy to write on, such as those made of clay, incised before firing. I don't have precise references at hand (look up Gaul on Wikipedia) but the book by Lambert on the Gaulish language (in French) contains photographs and facsimiles of numerous such inscriptions. It makes sense that most of those inscriptions should come from the Southern half of the country where many people must have been functionally bilingual earlier than in the North. A particularly rich source is the pottery workshop(s) at La Graufesenque in the department of Aveyron (not too far from Toulouse) which produced plates, bowls, etc by the thousands. The various potters marked their production by conventional signs in order to recover them from the enormous communal kiln. The drinking vessels with individual inscriptions were probably ordered or bought in the pre-firing stage, as the inscriptions show a great deal of individual variety. Perhaps some scribes specialized in writing such inscriptions for the pottery customers? Later inscriptions on metal seem to be common farther north (or perhaps they are just better preserved), and they deal with Gaulish cultural matters which deserved longer preservation, such as witches' curses and a calendar for religious ceremonies. These had to be made and inscribed by specialists, on order. As far as I know there is no record of Gaulish writing on more perishable material. Official matters of course were recorded in Latin.

marie-lucie said,

May 22, 2008 @ 11:37 am

p.s. on Gaulish:

I find the following in Robert Graves' "The White Goddess" (which contains a very extensive discussion of the Ogham alphabets and their uses):

"Julius Caesar records in his Gallic War that the Druids of Gaul used 'Greek letters' for their public records and private correspondence but did not consign their sacred doctrine to writing 'lest it should become vulgarized and lest, also, the memory of scholars should become impaired'".

Presumably they used the Greek alphabet to write on perishable materials, considered suitable for mundane matters.