You extraterrestrial tease, you

« previous post | next post »

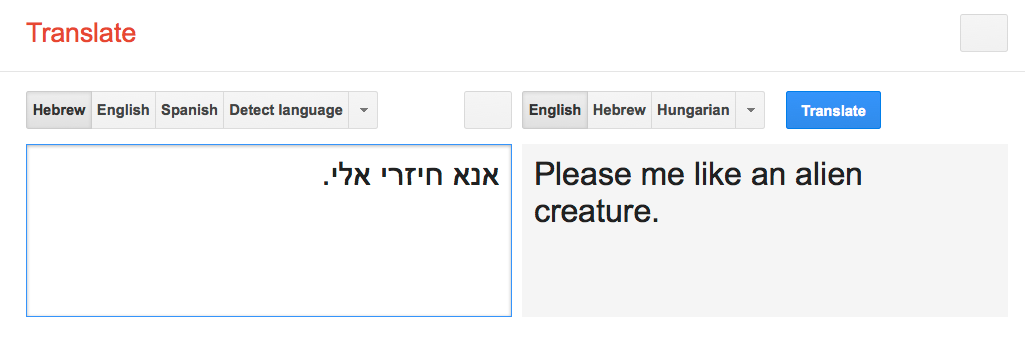

From Tal Linzen — Google Translate renders Hebrew "Please return to me" as "Please me like an alien creature":

Tal explains:

The first word אנא ['ana] means 'please' (though only in the request sense) and the last word אלי [e'laj] means 'to me'. The source of the mistranslation is the second word חיזרי, which can be either [xiz'ri] 'return (imperative, singular, female)' or [xajza'ri] 'extraterrestrial (adjective)'.The spelling for the 'return' sense is typically חזרי, but it's not that unusual to spell it with the vowel חיזרי. A more common spelling for the second form would be חייזרי, doubling the י to indicate that it's used as the glide [j] rather than the vowel [i]. Regardless of the spelling, though, it's surprising that 'extraterrestrial (adjective)' is more frequent than 'return (imperative)'.

At any rate Google Translate seems to have an output module that forces the English version to be a grammatical sentence, regardless of whether the syntax matches the original sentence or, for that matter, whether the senses of the words match the original senses. So 'please' (request) morphs into 'please' (satisfy) and the word 'like' is inserted without any obvious reason.

[h/t to Yoav Goldberg and Twitter user @kycisrael]

Update — I should note that all "statistical machine translation" systems, of which Google Translate is an instance, are applications of Shannon's Noisy Channel Model and Bayes' Rule, in which the choice of target-language alternatives jointly optimizes the probability of source-to-target mappings and target-language sequences. See "Noisily channeling Claude Shannon" (8/6/2012) for a brief introduction. Basically the metaphor is that the author of the source composed a message in English, but it was corrupted by a noisy transmission channel and thereby emerged in (say) French; the job at the receiver end is to undo the effect of the noise and recover what is most likely to have been the original message. So in that sense, there is always a built-in target-language model that plays a role in chosing among alternative possible outputs. But that "grammar" is a rather approximate one, typically some kind of n-gram model.

James Wimberley said,

November 28, 2014 @ 4:15 pm

John Scalzi's short story “How I Proposed to My Wife: An Alien Sex Story” is a good riff on the theme.

Yoav Goldberg said,

November 28, 2014 @ 4:38 pm

The word 'like' is probably there because חיזרי in the alien reading is an adjective. In fact the translation of חיזרי to ׳like an aliean creature' appears also when translating the word חיזרי on its own, and the phrasing suggests the use of some (non statistical) dictionary for translating this word.

Lance Nathan said,

November 28, 2014 @ 7:49 pm

As someone who's been using Google Translate a lot in recent months in order to evaluate parsers in languages he doesn't speak (such as Russian), I can say without reservation that you give Google Translate way, way too much credit.

David L. Gold said,

November 28, 2014 @ 8:06 pm

The sentence " […] it's surprising that 'extraterrestrial (adjective)' is more frequent than 'return (imperative)'" prompts comment.

In non-formal latter-day Israeli Hebrew, most of the historically imperative forms are not used. Rather, future-tense forms are used.

An example of each:

For the verb meaning 'sit', the historically imperative forms ARE used (I will romanize all forms mentioned here):

shev! 'sit down' (to one male)

shvi! 'sit down' (to one female)

shvu! 'sit down' (to more than one person)

Israeli Hebrew has two verbs meaning 'return': chazar (non-formal) and shav (formal). Since Mark Liberman mentions only the first of them, the following remarks are confined to that verb.

For chazar, the historically imperative forms (masculine singular chazor, feminine singular chizri, and plural chizru) are not used (remember, I am speaking here about non-formal latter-day Israeli Hebrew; those three forms ARE used in formal Israeli Hebrew).

Rather, in non-formal latter-day Israeli Hebrew, the imperative forms are the future-tense forms:

masculine singular tachzor! (literally, 'you will return!, you shall return!')

feminine singular tachzeri (literally, 'you will return!, you shall return!')

plural tachzeru! (literally, 'you will return!, you shall return!')

(To speakers of English and certain other languages, those forms may sound peremptory [imagine saying to someone in English "You will return at six o'clock'], but in non-formal latter-day Israeli Hebrew they are not; peremptory imperatives in Israeli Hebrew are consist of a subject pronoun and a verb in the future tense, for instance, ata tachzor beshaa shesh! 'you will return at six o'clock').

Now, it becomes clear why we should not be surprised that Google Translate interpreted the second word of the three-word sentence that Mark Liberman cites to be the adjective and noun meaning 'extraterrestrial' rather than the feminine singular imperative of the verb chazar, namely, in non-formal latter-day Israeli Hebrew, that adjective and noun is indeed more frequent textually than the feminine singular imperative chizri!

Lest anyone think that I am forgetting the feminine plural historical imperatives (shevna! 'sit down' and chazorna! 'return!' ), I am not. Since feminine plural imperatives are absent in non-formal latter-day Israeli Hebrew, they are not mentioned.

David L. Gold said,

November 28, 2014 @ 8:21 pm

Sorry, I see now that the post is Tal Linzen's.

Ran Ari-Gur said,

November 28, 2014 @ 9:51 pm

@David L. Gold: That's true in spoken Hebrew, but in written Hebrew imperative forms aren't nearly so uncommon; and one would have expected Google's bilingual corpora to bias toward the latter. (Googling "חיזרי" and looking through the first few pages, by the way, I find that almost all hits are instances of /xiz'ri/; very few are /xajza'ri/.)

I'm guessing that Yoav Goldberg has it right; if this translation came from a dictionary rather than from corpus analysis, then the lemma form /xajza'ri/ would have had an advantage over the non-lemma form /xiz'ri/ (lemma = /xa'zar/).

Y said,

November 29, 2014 @ 12:08 am

I don't think 'please' in the translation is the imperative verb. I suspect GT leaves it as is, after it's done with the UFO part, hoping the reader will make sense of it.

KWillets said,

November 29, 2014 @ 12:14 am

The best one can say about Google translate "forcing" the output to be a grammatical sentence is that it chooses the output alternative that has the most n-grams in common with training text. Given a bag of words like this it will reorder and interpolate to get something that looks, within a window of two or three words at a time, like the text it was trained on. There is no notion of the "sense" of a word beyond the other words that typically surround it.

David L. Gold said,

November 29, 2014 @ 12:51 am

Ran Ari-Gur's comment "That's true in spoken Hebrew, but in written Hebrew imperative forms aren't nearly so uncommon […]" (in response to something I wrote) invites comment.

In latter-day Israeli Hebrew, the controlling factor in the choice between (1) historically imperative forms (such as !חזור) and future-tense-forms-used-as-imperatives (such as !תחזור) is not the means (written or oral) by which the utterance is conveyed.(*)

Rather, the controlling factor is the location of the utterance (be it written or spoken) on the continuum of (in)formality.

That the degree of (in)formality is the controlling factor, not whether the utterance is written or spoken, is shown by the fact that both kinds of imperatives occur both in writing and in speech. For example,

1. In writing:

1.A. Historically imperative forms in formal writing, for example, on a door, משוך (= English PULL).

1.B. Future-tense-forms-as-imperatives in informal writing, for example, כשתקבל את המכתב הזה, תיצור אתי קשר 'when you get this letter, get in touch with me'.

2. In speech,

2.A. Historically imperative forms in formal speech, for example, לכל השוללים והפוסלים זכותנו לקוממיות ממלכתית נאמר: אספו ידיכם!

(the next-to-the-last word in this excerpt from a speech given by David Ben-Gurion at the Twentieth Zionist Congress on 7 August 1937).

2.B. Future-tense-forms-as-imperatives in informal speech, for example, תכין לי כוס קפה בבקשה 'make me a cup of coffee please'.

(*) A few verbs are exceptional in that their imperative forms are only or usually the historically imperative forms even in informal discourse (whether spoken or written), for example, !בוא הנה 'come over here!'.

Ran Ari-Gur said,

November 29, 2014 @ 3:21 am

@David L. Gold: It's true that, all else being equal, the true imperatives are more formal and the future-tense-forms-as-imperatives are more informal — and I don't think I implied otherwise. But I stand by what I wrote. In general, true imperatives occur much frequently in writing than in speech. (In part, this is because people tend to write more formally than they speak; though I'm not sure if that's the whole story. To some extent I think the converse may also be true, that people sometimes affect formality in speech by borrowing elements of a written style, and vice versa.)

Incidentally, your first example seems a bit tautological to me: you are interpreting משוך as formal because it is written with the true imperative; but if they replaced the sign with an audio recording on a loop, like airports have when you step off a moving walkway, I don't think the recording would just say "משוך". Rather, the use of true imperatives such as משוך is conventionalized on official signage. I'm not sure, but I think it may have as much to do with the tendency of signage to be terse as with its tendency to be formal.

Jen said,

November 29, 2014 @ 5:03 am

@Y: From experience with google translate, I'm pretty sure you're right. Having tried it, the output is broken into three sections, and you can choose to change 'me' to 'to me' if you think it improves the translation!

It just happens to make sense in English, and be funny.

GH said,

November 29, 2014 @ 5:17 am

Yes, I'm fairly positive that the grammaticality of the English sentence is entirely accidental. To the extent GT is even aware of the meaning of words, "please" here is probably used as the conventional politeness/request phrase, not as a verb.

To account for "like," is it possible that that is the verb? That it's some reduced form of "I would like you to…" or similar? Does the rest of the sentence in Hebrew, minus the alien creature bit, follow some pattern where something like that could often be the English translation?

Max said,

November 29, 2014 @ 8:49 am

"Forces" is a strong word, but this is basically true (or was, at least according to a talk by Peter Norvig on the subject). The translation uses two statistical models: one which measures the quality of translation, and one which measures the probability of the output as an utterance in the target language. They optimize a combination of these (with the latter weighted quite heavily).

John Lawler said,

November 29, 2014 @ 2:06 pm

Congratulations on Nouning an Adverb:

> The choice of target-language alternatives jointly optimizes

> the probably of source-to-target mappings and target-language sequences.

"Optimize the probably of mappings". I like it. Because syntax.

[(myl) A good example of how slips of the finger, unlike slips of the tongue, don't follow the Lexical Category Constraint.]

Marek said,

November 29, 2014 @ 3:21 pm

I find it somewhat likely the joint n-gram model probability of the final English sentence may be higher than of the more sensible alternatives, given that the corpora used for n-grams models and automatic translation usually come from news sources and fiction, and as a result contain very few imperatives in general.

A quick COCA search brings up 162 concordances for 'please me' and 62 concordances for 'please return'. On the other hand, 'please return to' occurs 26 times, and 'please me like' only once.

Aviah Morag said,

November 30, 2014 @ 8:01 pm

Note that חיזרי is not the most common spelling of this form, for the rare cases in which it is used today. The more typical spelling is חזרי, and in fact, אנא חזרי אלי yields an acceptable translation of "please come back to me."

Note also that "alien" is more typically spelled חייזר, derived from חייזרי and not חיזרי.

David L. Gold said,

December 1, 2014 @ 12:56 pm

Aviah Morag's post prompts these comments:

You write, "Note that חיזרי is not the most common spelling of this form, for the rare cases in which it is used today."

Comment:

As you know, normative Hebrew spelling allows yod as a mater lectionis after a chirik only when the vowel represented by chirik is historically long.

The vowel can be historically long only in an open syllable.

In the first syllable of the feminine singular imperative חזרי, the vowel is short because the syllable is closed, that is, it ends in a consonant /xiz-ri/), rather than in a vowel. Which is to say that the zayin is pointed with a quiescent sheva (שווא נח) rather than with a mobile sheva (שווא נע).

Consequently, writers of Hebrew aware of the fact that normative spelling does not allow yod here will write the form without that letter.

Since the historically imperative forms of the verb חזר are not used in latter-day non-formal spoken or written Israeli Hebrew, probably a large percentage of speakers of Hebrew are not even acquainted with those forms.

Consequently, probably most of the few people who would ever use the historically imperative forms of that verb in writing are the relatively small minority of users of the language who do know the rule about the use of yod as a mater lectionis.

And that is why, as you rightly say, חזרי is the more common spelling.

Which is to say, if a person knows enough Hebrew to know the historically imperative forms of that verb, she or he probably also knows that normative spelling does not allow a yod between the first and second letters.

Where one might expect the spelling חיזרי is in unpointed texts written for a mass audience, such as Yediot Acharonot, but it is hard to imagine that the historically feminine imperative singular form of that verb would appear in such a publication.

2. You are of course right that אנא חזרי אלי is fully correct. Textually, it is probably rare, at least in latter-day Israeli Hebrew because it is formal and when latter-day users of Israeli Hebrew want to be formal when picking this or that form of this or that verb meaning 'come back, go back, return', they are likelier to choose the verb שב rather than the verb חזר (not unexpectedly, therefore, the sign that storekeepers display when they are out of the store for a short while is אשוב מייד, which is more formal than אחזור מייד).

Therefore, if a speaker of latter-day Israeli Hebrew wants to say, whether in speech or in writing, 'please come back to me' or 'please return to me' to one female and that person wants to be formal or poetic, the wording chosen is likelier to be אנא שובי אלי than אנא חזרי אלי.

That is a second reason why אנא חזרי אלי is probably rare textually.

In fact, it is hard to think of why someone wanting to say 'please come back to me', etc. in formal spoken or written Israeli Hebrew would choose אנא חזרי אלי at all. Poets would not need that form for the meter because חזרי contains the same number of syllables as שובי does.

In sum, אנא חזרי אלי is correct Hebrew but unlikely to occur.

3. In connection with your remark that "'alien' is more typically spelled חייזר, derived from חייזרי and not חיזרי," you are of course right about the spelling of חייזר and about the irrelevance of the feminine singular form of the historical imperative of חזר to the etymology of that word (I do not think, by the way, that anyone here has suggested that etymology), but I wonder whether your etymology of the noun חייזר 'alien, extraterrestrial' is right.

On first hearing or seeing the noun, I said to myself, 'What a clever coinage. It was probably modeled on חית בר ['wild animal' ]." Thus, the fact that the first element of each of those two compound nouns consists of a word referring in some way to life and the fact that the second elements rime (/zar/, /bar/ ) suggested that etymology to me. Whether the etymology is right or wrong remains to be seen.

'

David L. Gold said,

December 1, 2014 @ 4:26 pm

To Lance Nathan's comment of 28 November 2014 (" I can say without reservation that you give Google Translate way, way too much credit."):

the Yidish (I prefer that spelling) of Google Translate is to a significant extent pseudo-Yidish (even when it comes to single words), to say nothing of translations of entire phrases and sentences from other languages, which more often than not cannot even be understood (unless you know the original text in the other language).

David L. Gold said,

December 1, 2014 @ 4:44 pm

To Ran Ari-Gur's comment on 29 November 2014: "you are interpreting משוך as formal because it is written with the true imperative; but if they replaced the sign with an audio recording on a loop, like airports have when you step off a moving walkway, I don't think the recording would just say "משוך". Rather, the use of true imperatives such as משוך is conventionalized on official signage."

I have read the passage quoted above several times, but cannot understand it. Since the second part ("[…] if they replaced […],") is hypothetical, could you please suggest what you think the spoken text might be, so that at least we would have a text, albeit a hypothetical one, to evaluate?

Aviah Morag said,

December 1, 2014 @ 11:41 pm

Funny… I originally thought of אנא חזרי אלי as "please call me back" (="please get back to me"). The verb שב would of course never be used in this context. In a literal context, שב is certainly more form (note that the sign stores would display is actually "תכף נשוב"). My native intuition is that the use of חזרי vs. חיזרי is more motivated by the fact that חיזרי (and חיזרו, by the same token) is quite different from the masculine חזור, as well as from the future forms תחזרי and תחזרו. Speakers are so unsure of these forms that they are likely to "hedge" by picking a spelling that could also be read as [xazri]. In more spontaneous writing, caught myself doing the same thing – and as a Hebrew translator, I should know better!

Ran Ari-Gur said,

December 3, 2014 @ 2:26 am

@David L. Gold:

> I have read the passage quoted above several times, but cannot understand it. Since the second part ("[…] if they replaced […],") is hypothetical, could you please suggest what you think the spoken text might be, so that at least we would have a text, albeit a hypothetical one, to evaluate?

Saying that it wouldn't (just) be "משוך" does not depend on what it what would be. There are lots of options, because it's less conventionalized. I think the tersest possibility is "נא למשוך" /,na.lim'ʃox/.

.

By the way, your description of "normative Hebrew spelling" does not correspond to the rules endorsed by the Academy of the Hebrew Language, nor to the rules followed by (say) Haaretz. Just because someone is aware of the spelling rules that you call "normative", that does not mean that they're likely to follow them in their own writing.