Phrasal trends in pitch, or, the lab subject's moan

« previous post | next post »

It's been a while since I posted a Breakfast Experiment™ — things have been hectic here — but yesterday in a discussion with some phonetics students, I learned that certain old ideas about (linguistic) intonation have passed out of memory. And in trying to explain these ideas, I posed a problem for myself that is a suitable subject a little hacking during this morning's breakfast hour. Attention Conservation Notice: We're going to wander in the history-of-phonetics weeds for a while here.

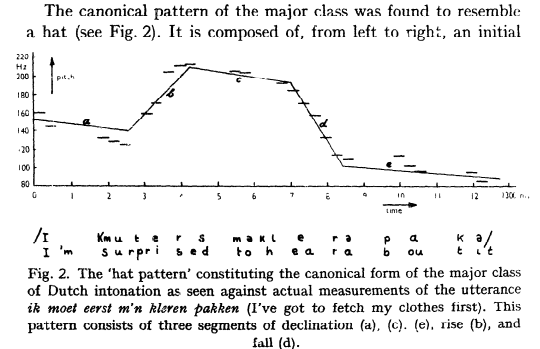

An example of the lost ideas is the "hat pattern", first described in Antonie Cohen & Johan t'Hart, "On the anatomy of intonation", Lingua 19, 1967.

The "hat pattern" idea (like other theories before and since) interprets intonation in terms of local and global properties of the time-function of fundamental frequency (f0), like "rise" and "fall" and "declination". In the 1960s and 1970s, most people thought of these properties as analogous to things like speeding up and slowing down, or getting louder and getting softer, or maybe raising and lowering your eyebrows — aspects of linguistic performance that speakers can control, and listeners can respond to, that nevertheless are not part of the phonological system governing the relationship between words and sounds in a given language.

An alternative view "phonologizes" intonation, representing it in terms of locally-linked "tones" analogous to the categories of a language with lexical tone, and explaining much of the apparently-global variation as the indirect consequences of such local choices (which may also be viewed as spelling out intonational "words"). Recently, this paradigm has come to dominate thinking in the field, to the extent that some students may not even recognize that there's an issue.

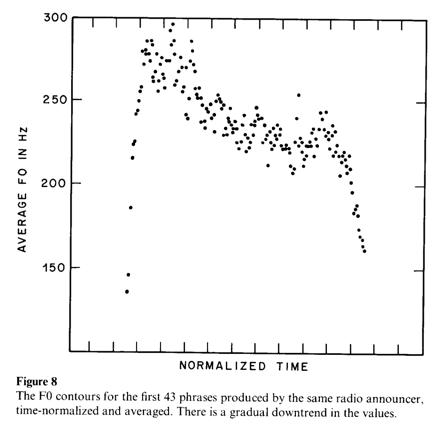

In 1980 or so, the hat-pattern metaphor was still popular, and when Janet Pierrehumbert and I looked at the average pitch contour of English phrases, we recognized it as something like the crown of a hat ("Intonational Invariance under Changes in Pitch Range and Length", pp. 157-234 in M. Aronoff and R. Oehrle, Eds., Language Sound Structure, MIT Press 1984):

This was convenient for our purposes, because we wanted to undermine hattism and promote a phonology-centric theory for both local (accent type) and global ("declination") aspects of intonation. In my current opinion, we (and others) may have been too successful, in that some younger linguists may not even recognize the possibility that certain aspects of prosody might not be phonologized after all.

If it's not clear to you what the issues are, consider the view that intonation is something like the hand gestures, postural changes, and facial expressions that accompany speech. Michael Studdert-Kennedy once explained the fact that British English (or at least RP) is stereotypically more tonally varied than American English, by suggesting that "the typical Englishman, being forbidden by social convention from waving his hands, waves his larynx instead". In fact, this is by no means entirely a joke — hand, body, and face gestures are typically aligned with stressed syllables and phrasal boundaries, just as aspects of F0 contours (i.e. laryngeal gestures) are.

Anyhow, in carrying on about discussing all of this with the phonetics students yesterday, it occurred to me that the empirical situation today is much better than it was in 1980, in that there are lots of published speech corpora out there, so that the exercise Janet and I carried out with our little collection of 42 radio-news-reader phrases can easily be done on a much larger scale.

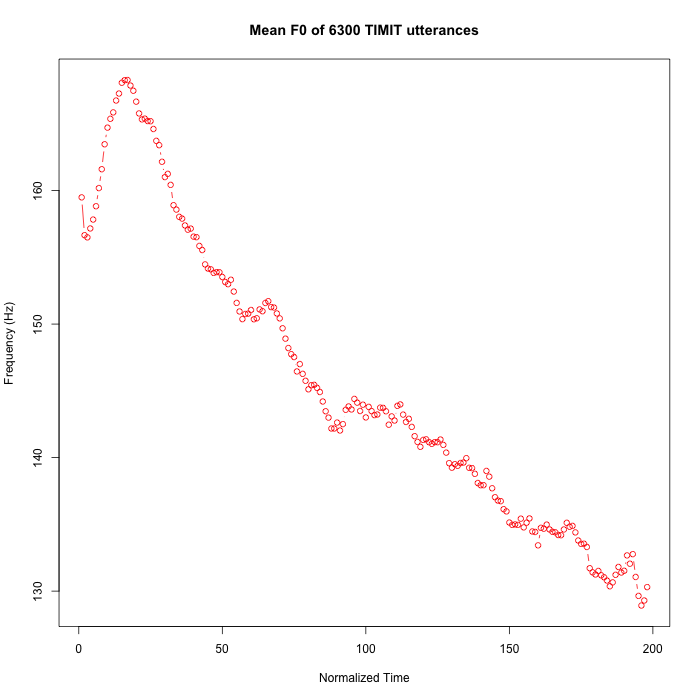

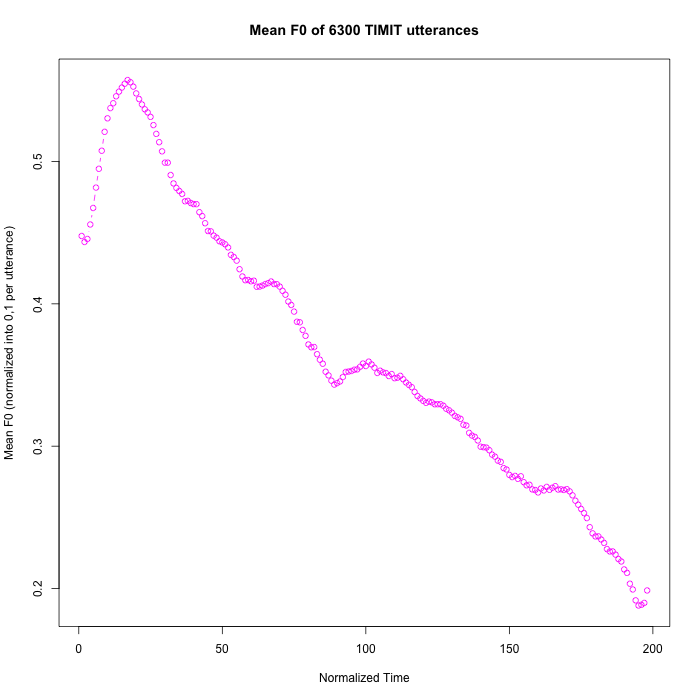

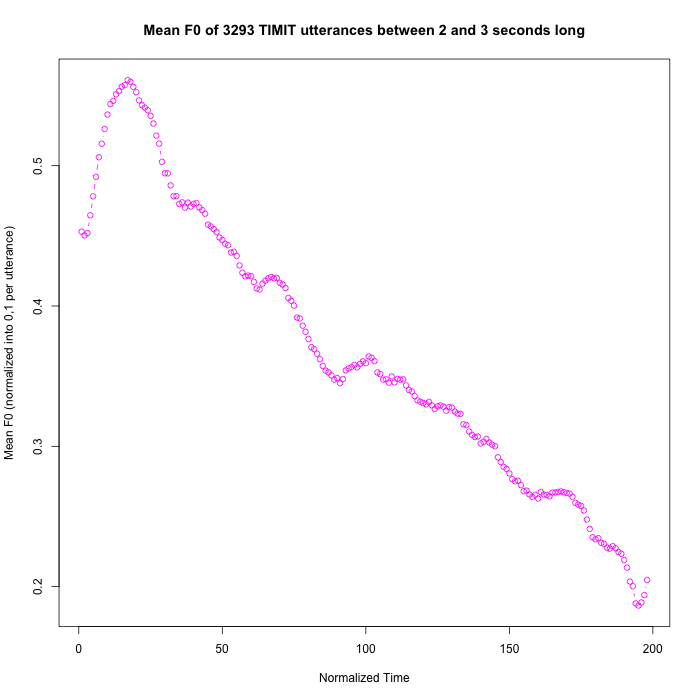

For example, it's easy to look at the average f0 trajectory of utterance in the TIMIT corpus. To do this, I (wrote a script that) extracted the pitch tracks for each of the 6300 read sentences in this collection, removed the parts before the speech starts and after it ends, re-sampled the sequence to 200 data points, and averaged each column of the resulting 6300 by 200 matrix (ignoring the nominally-zero values for unvoiced regions). The result is more like the train of a bridal gown than a hat, but anyhow it certainly shows the expected global downtrend:

If we first normalize each F0 contour into the range [0,1] corresponding to the span from its lowest value to its highest value, the time-normalized average smooths out some of the kinks (because random variation in higher-pitched utterances doesn't get privileged), but the overall shape is about the same:

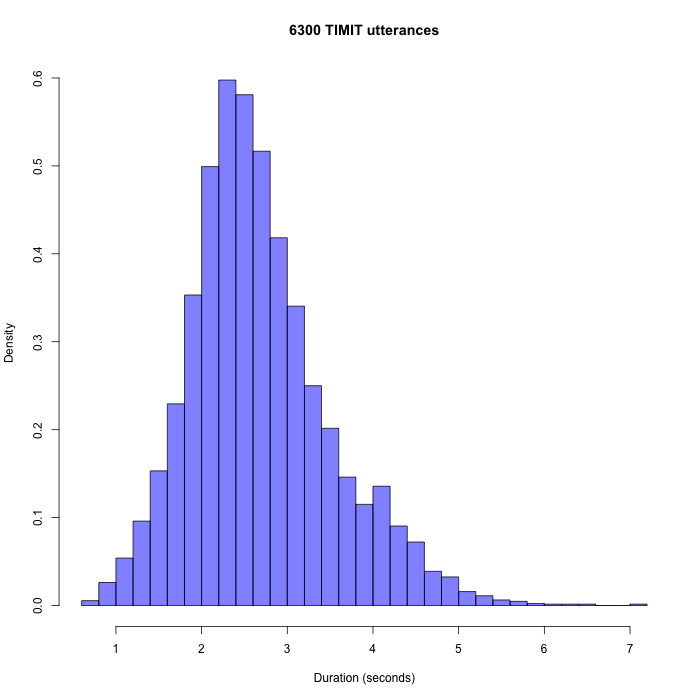

Of course, the range of durations in these utterances is fairly large, as the histogram below shows:

But if we limit consideration to utterances between 2 and 3 seconds long, the results are not very different:

We can "audible-ize" this pattern as a (rather mournful-sounding) acoustic display, rather than visualizing it in graphical form:

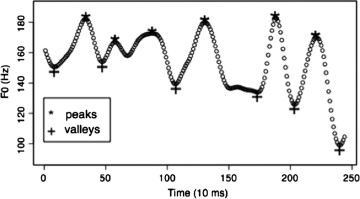

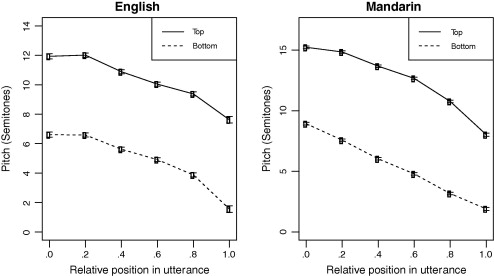

A few years ago, Jiahong Yuan and I took a more sophisticated approach to a similar problem, based on broadcast news material rather than sentences read in a phonetics lab sound booth ("F0 declination in English and Mandarin Broadcast News Speech", InterSpeech 2010; "F0 declination in English and Mandarin Broadcast News Speech", Speech Communication 65 pp. 67-74, 2014). We used a "convex hull" algorithm to find peaks and valleys in individual phrases, and then modeled the resulting "top line" and "baseline" sequences:

The abstract (of the 2014 Speech Communication version):

This study investigates F0 declination in broadcast news speech in English and Mandarin Chinese. The results demonstrate a strong

relationship between utterance length and declination slope. Shorter utterances have steeper declination, even after excluding the initial rising and final lowering effects. Initial F0 tends to be higher when the utterance is longer, whereas the low bound of final F0 is independent of the utterance length. Both top line and baseline show declination. The top line and baseline have different patterns in Mandarin Chinese, whereas in English their patterns are similar. Mandarin Chinese has more and steeper declination than English, as well as wider pitch range and more F0 fluctuations. Our results suggest that F0 declination is linguistically controlled, not just a by-product of the physics and physiology of talking.

Something that we didn't say in the abstract: These results also suggest that Janet and I were wrong (or rather, incomplete and therefore misleading) 30-odd years ago when we wrote (pp. 166-167):

[W]e find no clear evidence for phrase-level planning of F0 implementation. The major factors shaping F0 contours appear to be local ones. Potential long-distance effects are erratic and small at best3. All of our model's computations are made on pairs of adjacent elements, and the parameters of the transform need not be set differently for different phrase lengths. Significant phrasal position effects seem to be limited to a lowering of final pitch accents and therefore would fall within the scope of the two-pitch-accent window.

The phenomena collectively categorized as "declination" are, in our theory, explained by a combination of the final lowering effect, the frequent usage of stepping accents, and perhaps the statistics of relative prominence, We have no reason to think that the final lowering effect is varied for expressive purposes. As a result, its separation from tune and prominence is fairly simple.

3 See section 6.3. Of course, lack of evidence of long-range effects is not evidence against preplanning, but merely lack of evidence for it.

The idea that not all aspects of prosody should be "phonologized" has certainly not been lost — you can see an excellent summary of the issues in Jacqueline Vassière's chapter on "Perception of Intonation", in David Pisoni and Robert Remez, Eds., The Handbook of Speech Perception, 2005. But it seems that among some modern students, one side of the issue has largely faded out of consciousness.