"Keep Libel Laws Out Of Science"

« previous post | next post »

If you're in a hurry, just follow this link and (if you agree with it) add your name to a statement, hosted at Sense about Science, arguing that "The law has no place in scientific disputes".

If you've got a little extra time to spend, read on.

Back on April 19, 2008, the Guardian's "Comment is free" section published an article by Simon Singh, "Beware the spinal trap", in which he discussed the lack of evidence for chiropractors' claims to "help treat children with colic, sleeping and feeding problems, frequent ear infections, asthma and prolonged crying". But if you follow the link that I've given you, you'll find yourself reading a copy of Singh's text hosted in Russia, not an archived article on the Guardian's web site. That's because under legal threat from the British Chiropractic Association — which refused proposed remedies such as the right to publish a rebuttal — the Guardian decided to step back and withdraw the article.

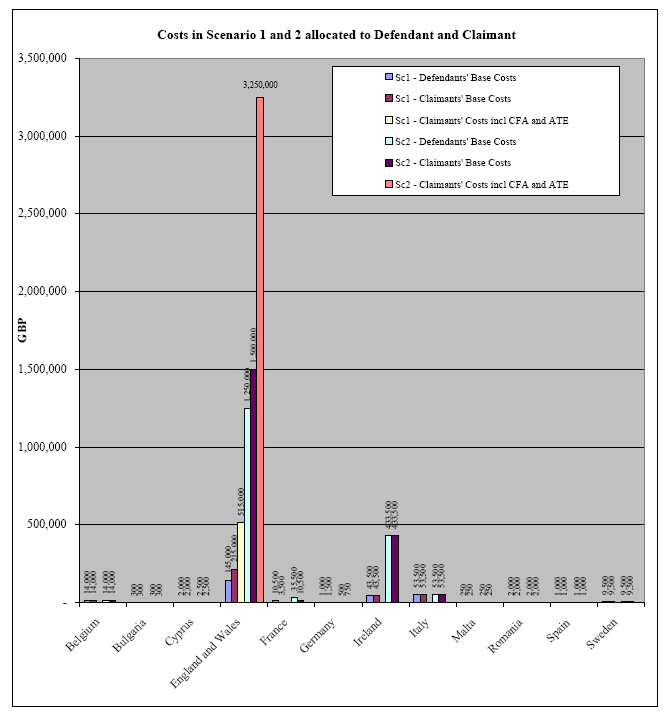

The BCA went ahead anyhow to sue Singh personally. And he's facing a very difficult legal situation, for two reasons. His first problem is a general one: British libel law puts the burden of proof on the defendant, who must justify the contested material, rather than on the plaintiff, as in the U.S. and many other countries. In addition, according to "A Comparative Study of Costs in Defamation Proceedings Across Europe", Centre for Socio-Legal Studies, Oxford, the costs of libel litigation in England are very high, both in absolute terms and in comparison to costs in other countries:

The data showed that even in non-CFA [Conditional Fee Agreement] cases (where there is no success fee or insurance) England and Wales was up to four times more expensive than the next most costly jurisdiction, Ireland. Ireland was close to ten times more expensive than Italy, the third most expensive jurisdiction. If the figure for average costs across the jurisdictions is calculated without including the figures from England and Wales and Ireland, England and Wales is seen to be around 140 times more costly than the average.

This can impose a substantial penalty on defendants even if they win, and is apparently why the Guardian decided to back down.

Singh's second problem is a 5/7/2009 ruling by the presiding judge in the English High Court, Sir David Eady. He ruled that Singh's article was a "statement of fact", so that Singh must establish its truth, not a "comment", for which he would merely have to establish that it was "fair". Worse, he ruled on the meaning of one of Singh's words in a way that makes him responsible for a "statement of fact" — which he never intended to make and doesn't believe — that is essentially impossible to prove to be true.

What Singh wrote was

The British Chiropractic Association claims that their members can help treat children with colic, sleeping and feeding problems, frequent ear infections, asthma and prolonged crying, even though there is not a jot of evidence. This organisation is the respectable face of the chiropractic profession and yet it happily promotes bogus treatments.

Eady decided that Singh's use of the word bogus implied conscious dishonesty on the part of the BCA. (See "Knowing bogosity", Language Log 5/11/2009, and "'Evidence': a scientific word or a legal one", The Economist 5/14/2009, for some discussion of the details and the merits of this ruling.)

As a result, it's not enough for Singh to prove that that chiropractic treatments for the cited ailments have not been shown to be effective — which is what he seems to me to have written. It wouldn't even be enough for him to prove that members or officers of the BCA should have known that good evidence is lacking for the effectiveness of such interventions. Rather, he must prove that the BCA, as an organization, knew that such treatments were ineffective, and promoted them anyhow in a conscious act of fraud.

You can learn more about this from the discussion and links in Simon Singh, "BCA v Singh: The Story So Far, 3 June 2009". Another good review is Phil Plait, "I know why the caged bird Singhs", 6/10/2009. Despite the odds against him, Singh has decided to continue to contest the case. And there's some recent indication that the Streisand Effect may be kicking in — see Phil Plait, "Chirapocalypse", Bad Astronomy, 6/10/2009. Indeed, the Sense About Science statement itself can be seen as a Streisand-Effect reaction:

The British Chiropractic Association has sued Simon Singh for libel. The scientific community would have preferred that it had defended its position about chiropractic for various children's ailments through an open discussion of the peer reviewed medical literature or through debate in the mainstream media.

Singh holds that chiropractic treatments for asthma, ear infections and other infant conditions are not evidence-based. Where medical claims to cure or treat do not appear to be supported by evidence, we should be able to criticise assertions robustly and the public should have access to these views.

English libel law, though, can serve to punish this kind of scrutiny and can severely curtail the right to free speech on a matter of public interest. It is already widely recognised that the law is weighted heavily against writers: among other things, the costs are so high that few defendants can afford to make their case. The ease and success of bringing cases under the English law, including against overseas writers, has led to London being viewed as the "libel capital" of the world.

Freedom to criticise and question in strong terms and without malice is the cornerstone of scientific argument and debate, whether in peer-reviewed journals, on websites or in newspapers, which have a right of reply for complainants. However, the libel laws and cases such as BCA v Singh have a chilling effect, which deters scientists, journalists and science writers from engaging in important disputes about the evidential base supporting products and practices. The libel laws discourage argument and debate and merely encourage the use of the courts to silence critics.

The English law of libel has no place in scientific disputes about evidence; the BCA should discuss the evidence outside of a courtroom. Moreover, the BCA v Singh case shows a wider problem: we urgently need a full review of the way that English libel law affects discussions about scientific and medical evidence.

Why should residents of other countries care about the vagaries of English libel law? There are general issues here of freedom of expression and of the fight against pseudo-scientific medicine. But in fact, it's not an exaggeration to say that English legal practice in this area threatens the whole world. Anyone anywhere can be sued in England, if what they have to say sufficiently annoys someone somewhere with enough money and motivation. Even if the offending statements are entirely true, the costs of defending the case will be cripplingly high. And there's the additional risk that true statements may be given an unintended interpretation, by a judge like Sir David Eady, that makes them false or in any case almost impossible to prove.

Perhaps the most famous example of this sort of "libel tourism" is the Funding Evil case, in which an American author was sued in England by a Saudi businessman. This led to an American publisher withdrawing a book that had never been published in England, and to a judgment of $225,000 against the author (who lost by default, not having the resources to mount a defense in England). The judge in that case was David Eady, the same one responsible for the strikingly pro-plaintiff construal of Simon Singh's use of the word bogus.

Some further light on Sir David's attitude to the role of libel law in public discourse may be shed by this note in his wikipedia entry: "In his practising days, he represented Singapore politician Lee Kuan Yew in his libel suits against the late opposition politician Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam."

[My only qualm about the Sense About Science statement, to which I've duly added my name, is that it can be taken to urge a distinction between "the way that English libel law affects discussions about scientific and medical evidence" and the way it affects others arguments, for example about politics. ]

Vincent said,

June 11, 2009 @ 10:46 am

Well, the judge may have taken the view that the defendant, without advancing evidence of the plaintiff's bogosity, might have published a statement intended to destroy the credibility of a branch of medicine, namely chiropractic.

Those who see the judge as being in the wrong here seem to have prejudged the issue themselves, on the basis that Singh is a sceptical hero who can say what he likes because he's so heroic, whilst the chiropractors had it coming and deserve to be publicly shamed.

The judge's critics, or in this case the critics of the English legal system, appear to think that it's up to the BCA to provide evidence that their treatments are effective.

But the concept of "evidence-based medicine" has a very short history indeed. It's not my specialisation, but the Wikipedia article traces it back to 1972, with the term first used in 1990.

I've no vested interest in any form of medicine, orthodox or otherwise, but the key phrase here seems to me "even though there is not a jot of evidence". It appears to imply an unwritten rule that no medical practitioner can offer any treatment whatever unless a Cochrane systematic review has been undertaken; and that therefore any treatment offered in the whole of history or indeed prehistory is bogus unless this type of review is undertaken.

[(myl) Indeed, perhaps we would be better off returning to the days when medicine was known as "the withered arm of science". But the point at issue here is not whether evidence-based medicine is a good idea or not, it's whether critics of allegedly ineffective or dangerous remedies should be silenced by prosecution for libel, as opposed to rational counter-argument.

Let's compare the response to anti-vaccination crusaders. As far as I know, no vaccine researchers, drug companies, or medical practitioners have tried to shut them up by suing for libel, though surely the case against Jenny McCarthy or Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is at least as good as the case against Simon Singh. ]

john riemann soong said,

June 11, 2009 @ 11:00 am

alright. where do we start rioting?

MM said,

June 11, 2009 @ 11:12 am

Libel and slander should be de-criminalized and "de-torted". They make no sense in the information age. When mere publication or a public platform made a writer or speaker credible, it made sense. There were once only a few people privileged enough to communicate to a mass audience. A writer/speaker had great impact.

Now we have YouTube, podcasts, Twitter, Facebook, e-mailing lists, forums, online reviews, comment sections below every article, and the blogs. So many blogs. Public address now belongs to the masses. The common individual may engage in recorded communication dozens, or even hundreds of times a day. And it follows that we also receive information from hundreds of sources a day, sources of varying degrees of credibility. We read some things, yes, that we take for gospel, but we have all become more incredulous. The public address is a much less grave threat to reputation than it once was.

Libel and slander torts, however, have a potentially chilling effect on this new facility of expression. The information economy and freedom of speech go hand in hand. Each (as we know them today) depends on the other. Restrictions on libel and slander have gone from discouraging the powerful from abusing their pulpits, to bullying ordinary people who express their ideas. Nevermind science.

dw said,

June 11, 2009 @ 11:15 am

"Those who see the judge as being in the wrong here seem to have prejudged the issue themselves, on the basis that Singh is a sceptical hero who can say what he likes because he's so heroic, whilst the chiropractors had it coming and deserve to be publicly shamed."

Those who see the judge as being in the wrong believe that the value of free speech far outweighs the damage suffered when an association of alternative medical practitioners is said to "happily promote bogus treatments". That the treatments do indeed appear to be bogus simply adds fuel to the fire. (uh – oh — I guess I'm going to get sued now!)

john riemann soong said,

June 11, 2009 @ 11:52 am

"credibility of a branch of medicine, namely chiropractic."

Hold on, since when was chiropractic a branch of medicine?

Ginger Yellow said,

June 11, 2009 @ 12:34 pm

" British libel law puts the burden of proof on the defendant, who must show that the contested material is not defamatory, rather than on the plaintiff, as in the U.S. and many other countries."

Technically speaking, the plaintiff does have to show that the material is defamatory. But the bar for doing so is very, very low – for reasons I can go into if you wish. The burden is then on the defence to provide a defence, for example that the defamatory statement is true, or privileged as an accurate record of an official hearing.

" It appears to imply an unwritten rule that no medical practitioner can offer any treatment whatever unless a Cochrane systematic review has been undertaken"

Well, there is a written rule in both the UK and the US that you cannot make unsubstantiated medical claims in marketing material. See the Chiropocalypse link for (hilarious) illustration.

As I've stated elsewhere, I think the focus on Eady's interpretation, while understandable, is mistaken. His interpretation was far from unreasonable (while not the only possible one), and even under Singh's own intended meaning the statement would still have been defamatory. It would just have been easier to provide a defence.

The problem is not primarily with Eady – although he does seem to have a zeal to interpret the libel law as harshly as possible for defendants – it's with the libel law itself.

~autolycus said,

June 11, 2009 @ 12:39 pm

Well, I think that free speech SHOULD be curtailed as a matter of principle. However, it should be curtailed intelligently.

I think that if stupid ideas are produced they should be taken to task, and if legislation allows you to exact a penalty for stupidity, that's even better.

In this particular case, if chiropractic can be proven bogus, then everyone wins. If it can be shown that there is reasonable doubt that it is bogus, then nobody really loses. Scientists shouldn't militate against laws that curtail free speech, since they can actually serve to aid the cause of science by chilling the urge to talk nonsense.

Scientists should rather put their money where their mouths are and PAY FOR SINGH'S LEGAL BILLS, if they are confident about proving bogosity.

dw said,

June 11, 2009 @ 12:45 pm

"Well, I think that free speech SHOULD be curtailed as a matter of principle. However, it should be curtailed intelligently. I think that if stupid ideas are produced they should be taken to task, and if legislation allows you to exact a penalty for stupidity, that's even better."

Has it occurred to you that if the cost of showing your idea is not "stupid" is, in the best case scenario, over 100,000 pounds, then quite a few "non-stupid" ideas may be suppressed as a result?

Charles Gaulke said,

June 11, 2009 @ 12:47 pm

"Those who see the judge as being in the wrong here seem to have prejudged the issue themselves," whereas we are to believe that you haven't?

Anyway, setting aside for the moment the importance of the case to free speech and the terrible chilling effect if the verdict is allowed to stand, I still don't understand the judge's defining of "bogus", even after reading about it here and elsewhere. Regardless of which party the burden of proof is on, how can it be up to the court to decide which interpretation of statements, rather than just which statements, the defendant must defend? Is it formally established in UK law that presenting a non-defamatory interpretation (ie, "you're wrong," versus, "you're a liar") is not a defense, or does the judge simply have enough leeway that Eady is free to act that way himself?

Ginger Yellow said,

June 11, 2009 @ 12:53 pm

"Scientists should rather put their money where their mouths are and PAY FOR SINGH'S LEGAL BILLS, if they are confident about proving bogosity."

Well, I'm not a scientist, but I've already committed to contribute to his defence fund if he starts one. As it happens, Singh has said he would prefer people to contribute to either Sense About Science, which I intend to, and/or to a future "fighting fund" in case other science journalists are sued in future.

It's not even a question of "proving bogosity". I don't think he has much chance of winning either the appeal of Eady's decision or the actual trial, given the way English law works. In this case, it's about ensuring that all the evidence gets aired. Surely that's exactly what science is about.

Aaron E. said,

June 11, 2009 @ 12:53 pm

Vincent, it appears that you're mistaken about what the judge's critics in this case, and by extension the critics of the application of libel law to these kinds of cases, are claiming. No one thinks that "it's up to the BCA to provide evidence that their treatments are effective." The BCA is free to pursue the justification of its claims by empirical evidence or not, as the fancy strikes it. But in this instance, the BCA wants to use the law to prevent Mr. Singh from making certain statements. The claim advanced by the detractors of the BCA's actions is that, to justifiably coerce someone not to claim X, where X is a statement of fact (as opposed to opinion, sarcasm, etc.), one needs evidence that X is false. In other words, everyone can say what they want by default, and only statements which have been definitively refuted are barred.

English libel law, as I (a non-lawyer) understand it, is not structured in this way. Anyone who makes a claim can be forced to defend it to the (high) legal standard of truth. In principle, this sounds like a good system — only statements known to be true will be made. However, in practice it is lacking. Because of the high cost of legal proceedings, only those with deep pockets can enter the public arena of debate. Since anyone can be forced to defend a statement in court, anyone who speaks up has to be willing to meet the up-front cost of a legal case. (This is independent of the question whether the winner can recover fees later.) If the disputed statement is on a significant empirical question such as the efficacy of chiropractic care (or vaccination), the studies to settle the question definitively could take years and cost millions. Furthermore, the latitude of interpretation given to judges such as Eady in these cases introduces a significant amount of uncertainty. In effect, everyone who makes an empirical claim is entering a lottery where the best possible outcome is breaking even, and the chance of significant loss is non-trivial. It doesn't take a professor of economic game theory to see that, under these conditions, the shallow-pocketed and the risk-averse will avoid making public statements on empirical matters, despite the fact that they may have significant, true contributions to make to the discussion.

Ginger Yellow said,

June 11, 2009 @ 12:58 pm

"Regardless of which party the burden of proof is on, how can it be up to the court to decide which interpretation of statements, rather than just which statements, the defendant must defend?"

A defamatory statement in English law is one which would lower the reputation of an individual in the eyes of a "reasonable person". Consequently a judge in a libel case has to decide what a reasonable person would take the statement to mean. It doesn't matter what the defendant thought he meant (except in certain limited circumstances, for example establishing malice in a Reynolds defence).

"Is it formally established in UK law that presenting a non-defamatory interpretation (ie, "you're wrong," versus, "you're a liar") is not a defense"

Yes – see above. Now obviously the availability or otherwise of a non-defamatory interpretation is going to influence's the judge's determinatin of what the sentence means, but the fact that something can be read innocently doesn't mean it will be by a reasonable person. The standard used is the "natural and ordinary meaning" of the words, allowing for innuendo etc.

dr pepper said,

June 11, 2009 @ 1:12 pm

Hmm, practitioners of "alternative medicine" make derogatory statements about conventional practice all the time. Perhaps some real doctors and researchers should take offense at things said by the BCA and sue them.

Ginger Yellow said,

June 11, 2009 @ 1:14 pm

"Anyone who makes a claim can be forced to defend it to the (high) legal standard of truth."

Anyone who makes a defamatory claim.

Picky said,

June 11, 2009 @ 1:40 pm

Yes – I understand how this looks from an American perspective, and I'm not at all prepared to defend the way the libel laws work in England, but just to explain where they come from … the plaintiff has to show he has been damaged – and if he shows the defendant has caused him damage, then the defendant has to show good reason (according to the available defences) or compensate the plaintiff for the damage caused. As far as it goes, that's not unreasonable.

Ginger Yellow said,

June 11, 2009 @ 1:52 pm

Well, not quite. The plaintiff has to show that there is potential for damage. Namely that the allegedly defamatory material has been published in England or Wales (which after various rulings basically means whether it has been published anywhere in the world), and that it would lower the reputation of the plaintiff in the eyes of a reasonable person. The plaintiff does not, for instance, have to demonstrate that an actual person has a lowered estimation of the plaintiff. Moreover, everyone is assumed to have a reputation to protect, even if they're highly disreputable people.

Taken together, that's pretty unreasonable.

Tom said,

June 11, 2009 @ 2:31 pm

I'm not sure it's helpful to solely focus on 'bogus'. On its own, I agree that 'bogus' doesn't necessarily imply fraud. But happily promote bogus treatments? To me, that does sound like the chiropractors knew that the treatments were bogus (in the, presumably undisputed, sense of 'ineffective' or 'false') and yet continued to promote them anyway. I like Simon Singh a lot, agree with him about chiropractic, and think the BCA are being stupid in continuing with this case. But I'm not sure there's anything wrong with David Eady's interpretation of what Simon wrote.

Francisco K said,

June 11, 2009 @ 2:34 pm

I do not understand why Dr. Singh is so adamantly opposed to Chiropractic. From what I saw, he had circumstantial evidence to back up very broad claims about Chiropractic. The article was biased, ethnocentric, and felt as non-scientific as he claimed chiropractic treatment to be. There are times when allopathic physicians will give a course of treatment based on their own experience that will end up being as ineffective as an adjustment, yet you don't see Dr. Singh warning everyone of the "wacky ideas" that some allopathic medical doctors have.

Scientific studies can support a hypothesis or not support a hypothesis; however, just because you do not support a hypothesis in a series of tests, this doesn't mean that what you did not support is false. It just means that you failed to support what you hypothesized.

Until Dr. Singh shows beyond circumstantial claims that Chiropractic or any other "wacky ideas" are detrimental, he should not be so vociferous in his accusations. I don't think that Dr. Singh's science makes any sense; therefore, why support the sense about science page. A person that wants to be heard for what they have to say instead of sensationalizing their claims shouldn't use such inflammatory language, "bogus."

[(myl) The purpose of the Sense About Science statement is not to support Simon Singh's view's of chiropractic theories and practices, but to oppose the use of libel litigation to shut off debate.

That said, Singh's original article does cite evidence that chiropractic interventions can be dangerous:

This sort of thing is apparently presented at much greater length in the book which his article introduced. ]

Ginger Yellow said,

June 11, 2009 @ 2:35 pm

I agree. It's certainly a reasonable interpretation, though not the only one. And even without a "knowing bogosity" interpretation, it clearly indicates reckless disregard for efficacy, which seems pretty defamatory to me. But I also think it would be pretty easy to justify in court, which knowing bogosity isn't.

Mark P said,

June 11, 2009 @ 2:42 pm

As I understand chiropractic in the US, medical conditions are not caused by external agents (bacteria, viruses) but by some kind of internal problem of the individual himself. In the past (a past possibly rejected today, at least publicly), all medical conditions could be treated by spinal manipulation. I see a distinct woo factor in what I read of chiropractic, something that is at odds with modern science and medicine. They refer to "vitalism" and beliefs that they admit cannot be tested scientifically. It seems entirely plausible that it can be shown that chiropractic does not conform to the modern scientific method and is thus bogus, at least as we now understand bogosity.

[(myl) That would be a reasonable thing to try to prove — if we were to accept that the burden of proof should be on the defendant in such cases. Unfortunately, as things stand, Singh could prove this and still lose the case, because what he is required to show is that the BCA as an organization engaged in conscious fraud. It's relatively easy to show (for example) that astrology is not scientifically supported; but it's impossible to prove that all astrologers are dishonest rather than deluded — because it's not true. ]

Nick said,

June 11, 2009 @ 3:51 pm

The campaign is a misnomer; Singh himself has written, "I have no problem with someone suing me or suing anyone else for libel, because there should always be an opportunity for redress." (Search for: Win or lose, the cost of fighting a libel suit chills science and journalism.)

[(myl) You should give a bit more of the quote:

]

Nick said,

June 11, 2009 @ 4:40 pm

myl: My point was that Singh is calling for the reform of English libel law (as your longer quote shows) but not for science to be exempt from it. The campaign is badly named.

Simon Spero said,

June 11, 2009 @ 4:55 pm

For one linguists take on just how insane the UK libel laws are, see Pullum (1985,1987). (Both articles are collected in TGEVH). If you've ever wondered if all those example sentences about John and Mary might need to be run past legal, the answer is here.

To see just how much harm they can do, look at the case of Robert Maxwell, who won libel cases against Private Eye for claiming that he was stealing money from his corporations Pension Fund, only for it to be discovered, after his suicide, that he had been etc.

Pullum, Geoffrey K. (1985). “Topic … comment: The Linguistics of Defamation”. In: Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 3.3, pp. 371–377. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00154268

— (1987). “Topic…comment: Trench-mouth comes to Trumpington Street”. In: Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 5.1 (Feb. 21, 1987), pp. 139–147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00161870"

Jr said,

June 11, 2009 @ 6:08 pm

I am surprised that you could discuss libel and science and not mention the recent case involving lie detectors and libel.

[(myl) Well, we covered it at tedious length back in April — and David Beaver did his best to provoke the miscreants with the lead sentence "A bullshit lie detector company run by a charlatan has managed to semi-successfully censor a peer reviewed academic article" — but you're right, it would have made sense to cite it here. The lie-detector company, Nemesysco, didn't actually sue Equinox Publishing, but (because of the absurdly plaintiff-friendly nature of the British libel system) they were able to get a peer-reviewed scholarly article withdrawn merely by threatening to sue. ]

Francisco K said,

June 11, 2009 @ 10:11 pm

I agree with Nick about science in relation to libel.

In response to myl: I read the original Dr. Singh text, and what you quoted was the biased anecdotal evidence that I was referring to. Let's suppose that all of the evidence was correct as stated which I don't believe it is completely–the source studies had self reported minor soreness in some patients which equaled chiropractic not worth it, though this same sort of soreness could be found from other treatments. Dr. Singh's tone is what got him in trouble. His word choice and tone, in my opinion, demonstrated a desire, unconscious or otherwise, to cast aspersions on UK Chiropractic. I'm not a chiropractor or anything, but he wouldn't be in this situation if he would have reported/written with less intolerance.

misterfricative said,

June 12, 2009 @ 1:58 am

As stated in the OP, Judge Eady ruled that 'Singh's use of the word bogus implied conscious dishonesty on the part of the BCA.' (my italics)

I find this ruling willfully extreme at best, and given the judge's track record, I can't help wondering if this might perhaps be an instance of psychological projection.

Trond Engen said,

June 13, 2009 @ 1:23 pm

I've been entertaining the idea that judge Eady has a secret agenda here: He's forcing Singh to take the fight he never wanted to and prove that there's indeed wilfull deception on the side of the chiropractor's association.

Thomas D said,

June 14, 2009 @ 6:10 pm

I'm not sure what this libel action, or this post, really have to do with 'keeping the law out of scientific disputes'. The case isn't about the efficacy, or lack of it, of chiropractic treatment, or about whether scientific claims can be made the subject of libel trials. It's about whether Singh called the chiropracters dishonest or negligent.

Singh or anyone else was open to write to his heart's content that there is no evidence for the efficacy of the treatments, without getting sued, if he could only refrain from defaming the people who provided them. As a writer he knew very well how to do that.

If one reads the whole sentence under dispute, it seems very plausible that the plain meaning of it is that the chiropractors promoted their treatments despite knowing they were worthless, or at least while being utterly negligent on that point. That is defamation.

How about some linguistic analysis of the difference between

"This organisation, the respectable face of the chiropractic profession, promotes treatments that are in fact bogus"

and

"This organisation is the respectable face of the chiropractic profession and yet it happily promotes bogus treatments."

Surely the juxtaposition 'respectable' / 'and yet' / 'happily' / 'bogus' produces a strong implication of dishonesty or negligence.

Evan said,

June 17, 2009 @ 5:01 am

sounds like someone should write an emacs macro to prepend "I believe that" to every sentence published in the UK.

Eric Mitz said,

June 9, 2012 @ 1:58 pm

Just an aside, I wish the mainstream press were as diligent in pursuing prosecutorial articles about the claims made by some pharmaceutical companies…