How fast do people talk in court?

« previous post | next post »

This morning, let's take a break from the analysis of headlines, and look at some phonetics research. Recently, Jiahong Yuan and I have begun working with a woman who aims to revise and improve tests that are used to certify court reporters. (For some background about the techniques and devices that the court reporters must learn to use, see here or here.) The (preliminary) results of our (pilot) experiment may be interesting to some of you; I think that they also point to a broader opportunity for linguistic research of other kinds.

Among the questions that our partner needs to answer is what speaking rates, in words or syllables per minute, a court reporter is likely to encounter. Obviously, there's a great deal of variation, depending on the nature of the situation and the characteristics of the speaker. She doesn't want to make the tests too easy, by using material that's unusually slow or unusually simple, or by allowing too many errors at normal rates. Nor does she want to make the tests too hard, by using material that's atypically fast and complex, or by excessive penalties for errors at abnormally fast speeds.

In short, she'd like to be able to make predictions, based on the test results, about the error rates that testees will achieve across the range of situations they are likely to encounter in doing their job. In order to do that, she needs to be able to characterize what that range of situations really is. And an important dimension of characterization is speaking rate.

Now, overall speaking rate is easy to determine. You just count words in the transcript, measure time in the recording, and divide: result, words per minute. For syllables, you just look all the words up in a pronouncing dictionary, and add up the syllables, and divide by the same measure of elapsed time. (There are plenty of conceptual issues here about what a word is, exactly, and how many syllables to attribute to certain classes of sounds, and how to treat reduced pronunciations in rapid speech, and so on. But these are all essentially irrelevant to the topic under discussion, because the same metrics are used on the test materials as in the norms.)

However, overall speaking rate is not the right measure. A deposition or hearing will have some periods of silence, and there will be other times when a speaker is speaking slowly, choosing words with great care. Those periods, where there are relatively few words per minute, will then be balanced by periods when the rate is faster.

For norming the tests, it's important to know what the distribution of local rates actually is. A would-be court reporter may be able to keep up easily in transcribing speech at the overall rate or below, but may be completely lost when things get just a little faster — and it might be that (say) 40% of the material would then be beyond their capabilities.

In order to get some information about what the distribution of local speaking rates is really like, we plan to process a large and representative sample of real-life examples. To establish and validate the procedures, we began with an initial sample of 40-odd recordings with transcripts. The recordings were .wav files, made under normal conditions in the course of various depositions and court proceedings, and the transcripts were MS Word files, in the standard format for court documents of the relevant kind.

After some preprocessing, we ran these through a system that aligns the words to the audio, using techniques from speech-recognition technology. (See here, here, and here for some additional discussion of this same set of programs.) Spot checks indicate that the alignment was very accurate, as we've come to expect after testing this system on many different kinds of material.

The results of the word-level alignment look something like this (the two numbers on each line are the starting and ending time of the corresponding word, in seconds counting from the start of the recording):

404.443310658 404.553061224 "IT'S"

404.553061224 404.722675737 "NOT"

404.722675737 404.872335601 "YOUR"

404.872335601 405.251473923 "JOB"

405.251473923 405.371201814 "TO"

405.371201814 405.560770975 "DIG"

405.560770975 405.740362812 "INTO"

405.740362812 405.929931973 "ALL"

405.929931973 406.069614512 "THAT"

406.069614512 406.448752834 "STUFF"

406.448752834 406.57845805 "IS"

406.57845805 406.638321995 "IT"

And internally, the aligner has also produced an alignment of the phonetic segments involved (as per the available dictionary pronunciations, anyhow), like this:

404.443310658 404.47324263 "AH0"

404.47324263 404.503174603 "T"

404.503174603 404.553061224 "S"

404.553061224 404.582993197 "N"

404.582993197 404.692743764 "AA1"

404.692743764 404.722675737 "T"

404.722675737 404.802494331 "Y"

404.802494331 404.842403628 "UH1"

404.842403628 404.872335601 "R"

404.872335601 405.031972789 "JH"

405.031972789 405.22154195 "AA1"

405.22154195 405.251473923 "B"

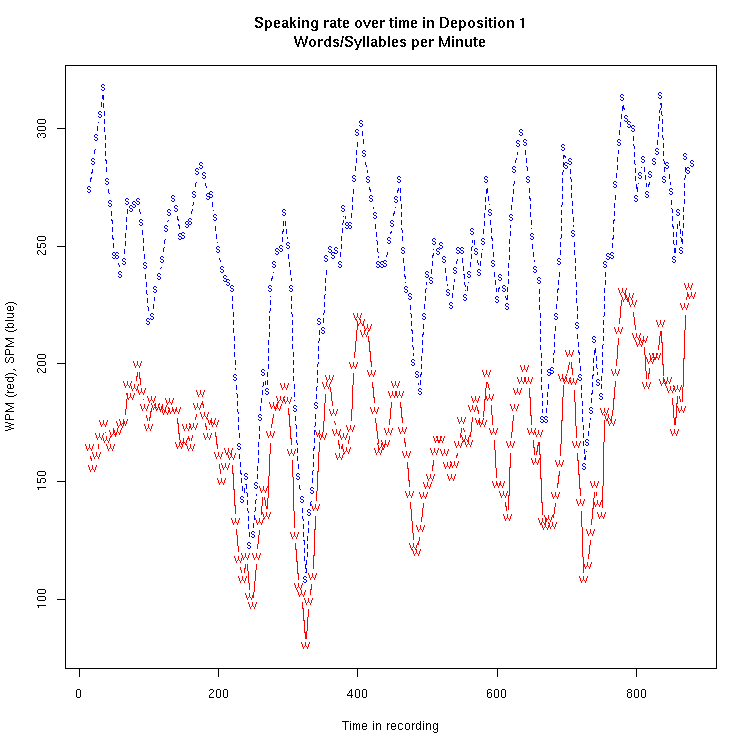

We then wrote a script that scans these files and produces local speaking-rate estimates, over a moving 30-second window that scans from the start of the transcript to the end. Here's what the resulting time-function looks like, for one deposition selected at random:

(Click on the image for larger version. If you have a small screen, you might want to right-click and view the image in separate browser window.)

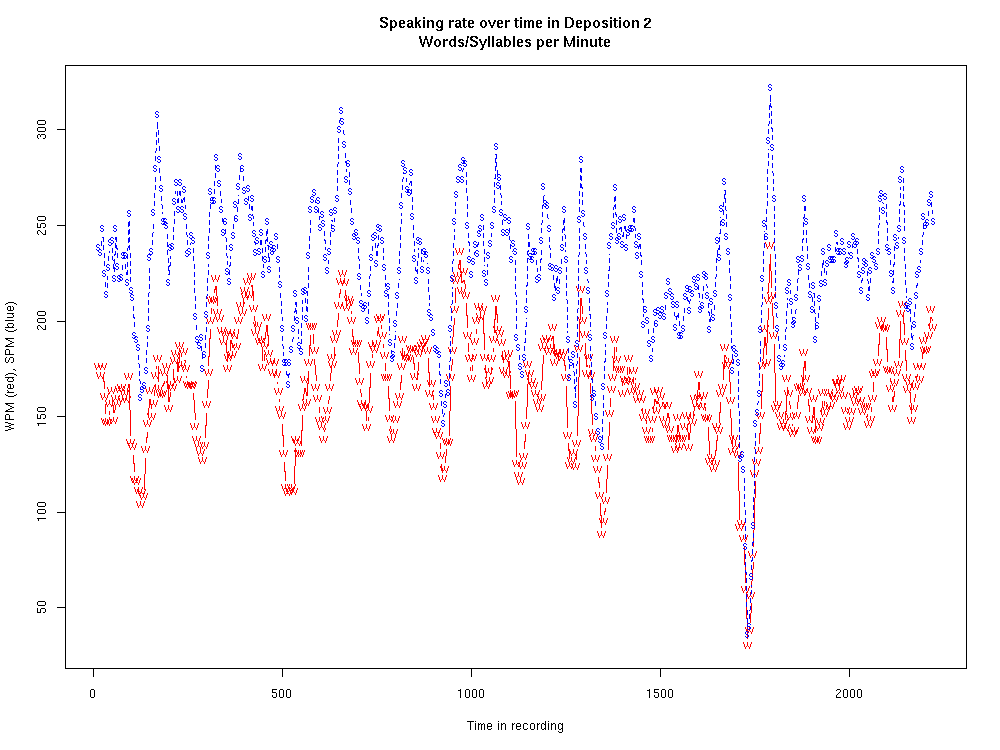

Here's another example of the same sort:

For the second example, the average rate was 164 wpm, and the median 165. The maximum rate (in a 30-second window anywhere in this particular deposition) was 239; the 90th percentile was 200; the 95th percentile was 210.

In terms of syllables rather than words, the mean rate was 226 per minute, the median 232, and the maximum 322. (The average ratio of syllables to words was 1.38, with a minimum (for any 30-second window) of 1.05 and a maximum of 1.82.

For the (small) sample we've looked at so far — 41 transcribed passages amounting to around 10 hours in total — the maximum over any 30-second window was 284 wpm. About 1.7% of the 30-second segments were faster than 225 wpm, and only around 0.25% were faster than 250 wpm.

According to the Wikipedia article on Court Reporting

The minimum speed needed to become certified by the NCRA is 225 words per minute. The NVRA requires a minimum speed of 250 words per minute to qualify for certification.

Skilled individuals can handle speeds well over 300 wpm. My understanding is that tested rates are adjusted downwards for errors, as in the case of typing tests. The purpose of the work described here is to provide a better quantitive basis for predicting what such numbers mean in terms of coverage, and for deciding what the standards for certification should be.

There are many kinds of science. Some research is hypothesis-driven, where the goal is to confirm or refute a theory, or to determine which of two alternative theories is better. In other cases, the goal of the research is just to see what's out there, so to speak. Such mapping expeditions can be motivated by abstract curiosity, by relevance to theoretical questions, or by practical applications.

This particular piece of research is obviously a mapping expedition, motivated by a particular practical question, which was posed originally in a piece of email from a stranger. What I've described in this post is just the beginning of the project, not the end; but I'm now confident that the techniques we've developed for other applications will work on this material as well, and will enable us to give a useful answer to the practical problem at hand.

In this case, the practical application is not of great interest outside the community of court reporters. But there's a broader context that's worth thinking about. There are millions of hours of transcribed audio out there: court proceedings, oral histories, broadcast interviews, political speeches, audiobooks, and so on. The techniques used in this case, with some modifications and adaptations, can make this stuff available as raw material for research in all of the scientific disciplines that deal with spoken language.

[Update 3/24/2009: Some interesting commentary here, including this:

I'm currently in a trial and during cross of the defendant today, the WPM meter never went below 250. It's hot, it's heavy. Can I get it? Absolutely. Do I stop the proceedings if I can't get it? Absolutely. But I try to hang on as best as I can, knowing they will eventually stop to look at an exhibit or take a breath at some point.

]

Craig Daniel said,

March 21, 2009 @ 11:53 am

There is actually one field that cares about this as much as court reporters, and for the same reason: court interpreters. (I'm currently training my simultaneous interpretation skills in order to be one, and am aware that the tests are done at too low a speed and don't want to pass the test and then find that I can't do the job.)

Jesús Sanchis said,

March 21, 2009 @ 1:06 pm

I agree that there's a lot of potential in this kind of research, which looks quite serious. However, when I read the post it reminded me of a very funny sketch from the popular BBC comedy series "Little Britain", as an example of someone ('Vicky Pollard') speaking very quickly in court. This is the YouTube link:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8s1C_8qg-e0

Stephen Jones said,

March 21, 2009 @ 2:46 pm

Surely they could record the deposition and then get somebody to type it. As the recording could be kept there would be a record against human error.

[(myl) Well, in the first place, there is indeed a recording, at least in the cases under discussion here — that's how we're able to do what's described in the body of the post. So in some cases, the issue is mainly how to get an accurate transcript with a minimum of human labor.

There are other cases where it also matters that the transcript is available in real time. In my (limited) understanding, the reasons to do this in court include making it possible for portions of the transcript to be read back when directed by the judge, and allowing access to the proceedings by hearing-impaired people. The same sort of techniques are used for real-time closed captioning. This web site of the California Official Court Reporters Association discusses a (future?) system where

Finally, I believe that the legal policies and practices in question originally evolved at a time before the invention of effective recording devices, when (originally manual, then mechanical) shorthand was the only way to create transcripts. I imagine that some of the rules (for example about how the official transcripts of depositions are created) reflect that history to some extent.

However, if you think about the difficulty of guarding against the creation of fraudulent, artificially-edited digital recordings (no matter how accurately transcribed), it makes sense to require that the transcript should have to be produced by some professionally-certified third party who is actually present when the testimony is taken. ]

dr pepper said,

March 21, 2009 @ 9:20 pm

One of my customers is a lawyer. Recently he called me to install some new software for a transcript service he'd signed up for. It's called For the Record. Anyway, to my surprise there was no transcript on the disk he got, just a recording in a proprietory format. That's why he needed my help. I went to the appriate website and downloaded and installed the appriprate player. I then listened to the first couple of minutes of hte recording. It was awful. I'm not a sound tech but i'm pretty sure that the microphone was not properly positioned or shielded. It might even have been the wrong impedence. The voices were indistinct, easily overwhelmed by shifting chairs and other background noises.Obviously, that is inexcusable, but at least if there had been a transcript there'd be a chance of knowing what the words were.

Mark A. Mandel said,

March 21, 2009 @ 11:15 pm

Presumably the X-axis is labeled in seconds. I found it hard to think about it that way, so I added minutes labeling — by hand, so it's close enough but not exact. See http://i155.photobucket.com/albums/s317/thnidu/linguistics/speakingrateminutes.png .

Peter Seibel said,

March 21, 2009 @ 11:37 pm

I think in some courts where they are trying to replace stenotypists with audio recording, they still have to pay someone to sit there and listen under headphones to make sure everything is being recorded reasonably–you don't want to get to the end of the trial and discover the tape is full of background noise, etc. When you have a live court reporter, one of the things they can do is ask people to repeat things if they didn't hear it.

Interestingly, back in the day of pen reporters (i.e. people who recorded the the goings on in courts using pen and paper) the top reporters could also do > 300 wpm, at least on certain kinds of probably formulaic legalese.

Stephen Jones said,

March 22, 2009 @ 6:49 am

Thanks for the full reply. Thinking of it stenographers can pretty well record at the rate of speech (last time I was hauled up in court the secretary sat next to the judge with an old typewriter and was able to give the judge the official judgement to sign at the end of the five minute hearing.

mgh said,

March 22, 2009 @ 9:58 pm

I'm imagining that some amount of what a court reporter transcribes is the equivalent of "boiler-plate" — phrases that recur frequently in court proceedings. Are you making any adjustment for their effects? How much of a transcript do they comprise? I'm guessing they are spoken more quickly but are much easier to transcribe than unpredictable text spoken at the same rate would be.

Laura Payne said,

March 23, 2009 @ 12:30 pm

I know this is not exactly the same as court reporting, but I just posted about the differences in speech rate by language and I would love to know what you and your readers think about the subject and about the information I found on the subject. http://walkinthewords.blogspot.com/2009/03/speech-rate-by-language.html

Robert said,

March 24, 2009 @ 8:34 am

I wonder if queueing theory is relevant to this at all. That is to say, a court reporter would have two skills, keeping what they've just heard in their memory, and transcribing it at some particular speed. That is to say, a slower writer could compensate by having a better memory, giving a nearly equivalent result on certain distributions of word rates.

Sandra said,

March 24, 2009 @ 11:22 am

I work as stenographer in the German Parliament. We still use pen and paper, and on average we can write more than 300 syllables per minute. Our work could not be used for research on spoken language though because we do revise a lot to make the spoken more readable. I guess we are not the only ones who do not transcribe speech word by word.

Kathleen O'Connor Powers said,

April 9, 2009 @ 10:11 am

court reporters are transferring what is heard into writing instantaneously, when the speeds are exceptionally high. We need to have a good sense of the essence of the subject matter, because there is no time for memory retention to any large extent, you are processing the info so quickly and making split-second decisions. As in any skill, you fall back on your training in times of crisis, the "retention" memory time is too much of an impediment to fast writing…