It's all about who?

« previous post | next post »

Sharon Jayson, "What's on Americans' mind? Increasingly, 'me'", USA Today 7/10/2012:

Sharon Jayson, "What's on Americans' mind? Increasingly, 'me'", USA Today 7/10/2012:

An analysis of words and phrases in more than 750,000 American books published in the past 50 years finds an emphasis on "I" before "we" — showing growing attention to the individual over the group.

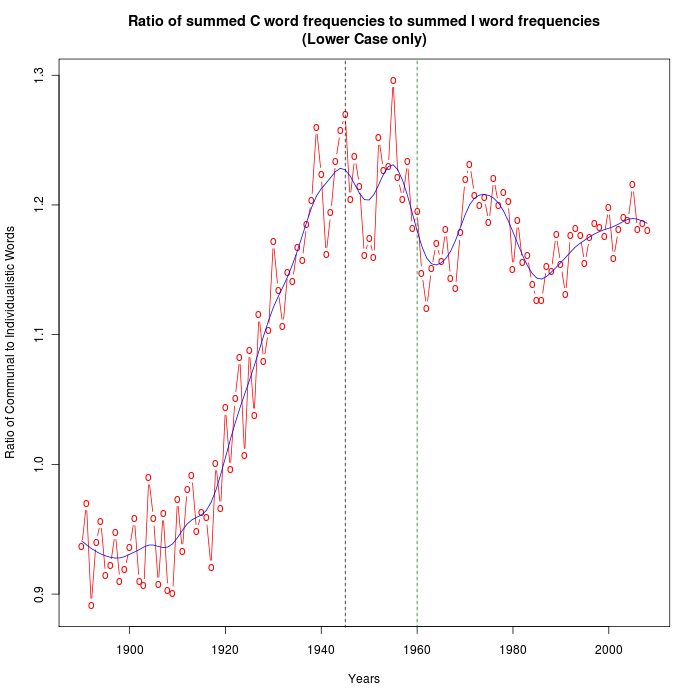

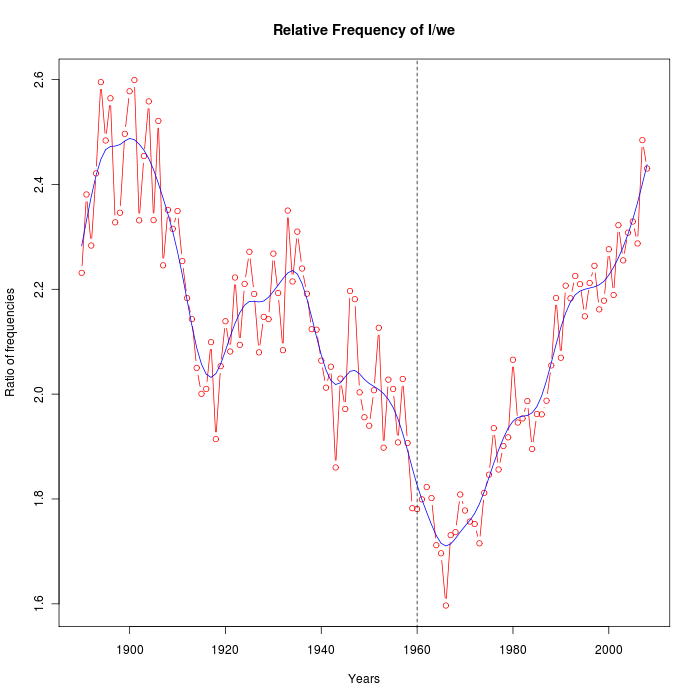

This is actually true as stated. If we take the counts from the "American English" unigram dataset in the Google Books ngram collection, and extract the year-by-year counts for the letter strings in question, the frequency of "I" has increased relative to the frequency of "we" over the period since 1960 — to the point where the ratio of frequencies is almost as high as it was in 1900:

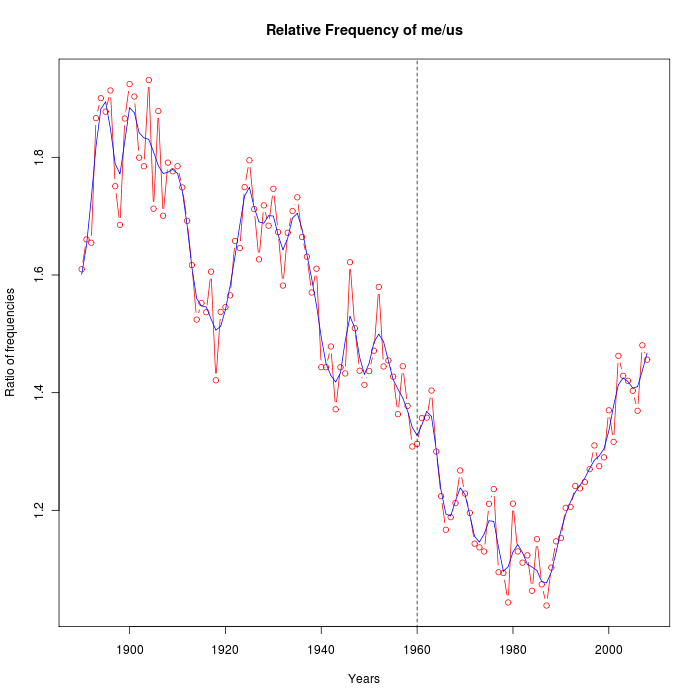

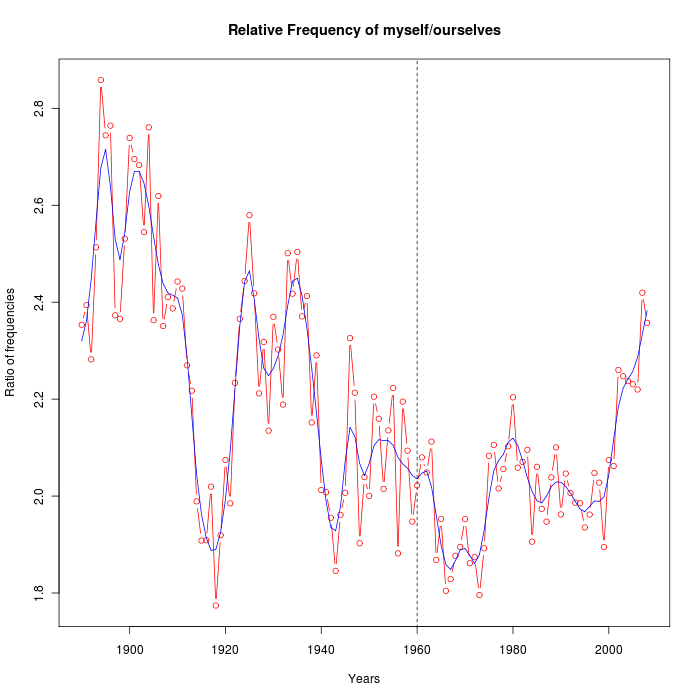

Perhaps we ought to worry a bit about how often "i" is the roman numeral or the initial; but looking at the relative frequency of "me" vs. "us", or "myself" vs. "ourselves", shows a generally similar pattern over time (though the recent rise seems somewhat delayed, and is substantially smaller):

|

|

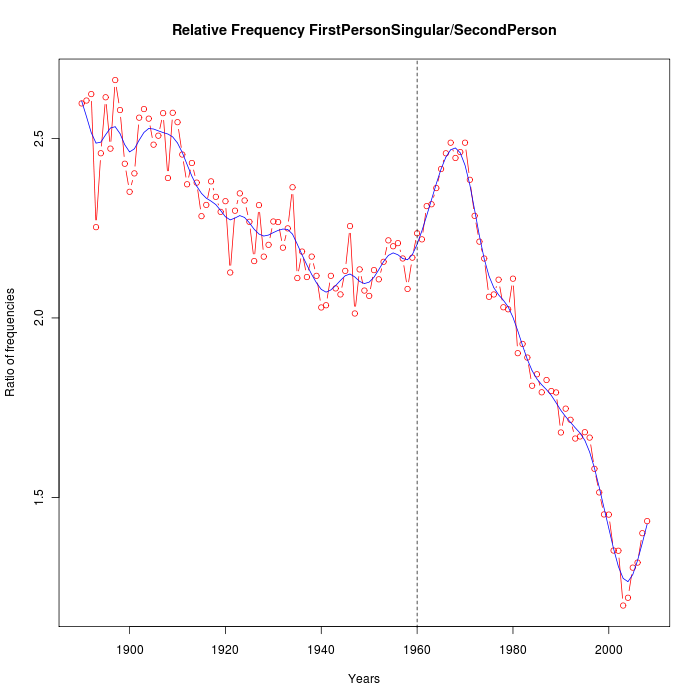

The changes from 1900 to 1960 are at least as striking as the changes from 1960 to the present. And if we compare "I" and its pronominal associates to "you" rather than to "we", we see a strikingly different pattern:

But let's push forward for now.

The USAToday article is based on work by Jean M. Twenge, W. Keith Campbell, and Brittany Gentile, "Increases in Individualistic Words and Phrases in American Books, 1960–2008", PLoS One 7/10/2012, which concludes that:

Individualistic words and phrases increased in use between 1960 and 2008, even when controlling for changes in communal words and phrases. Language in American books has become increasingly focused on the self and uniqueness in the decades since 1960.

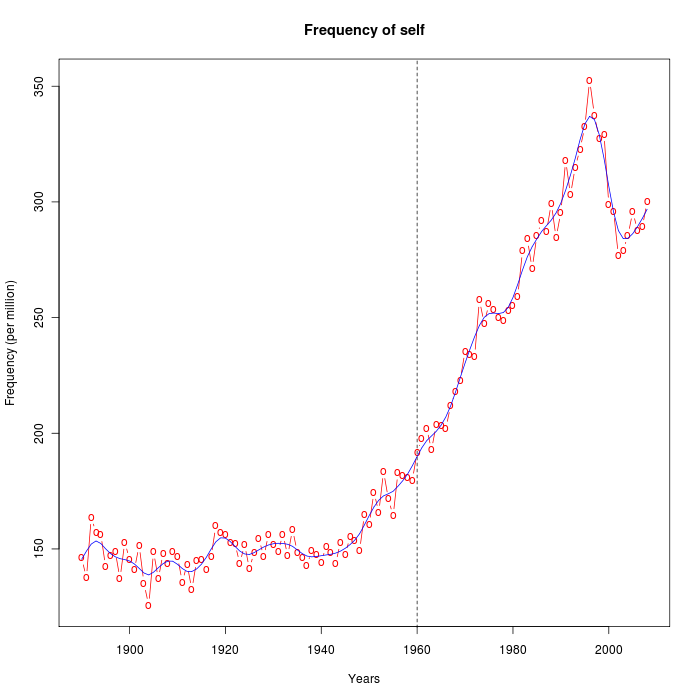

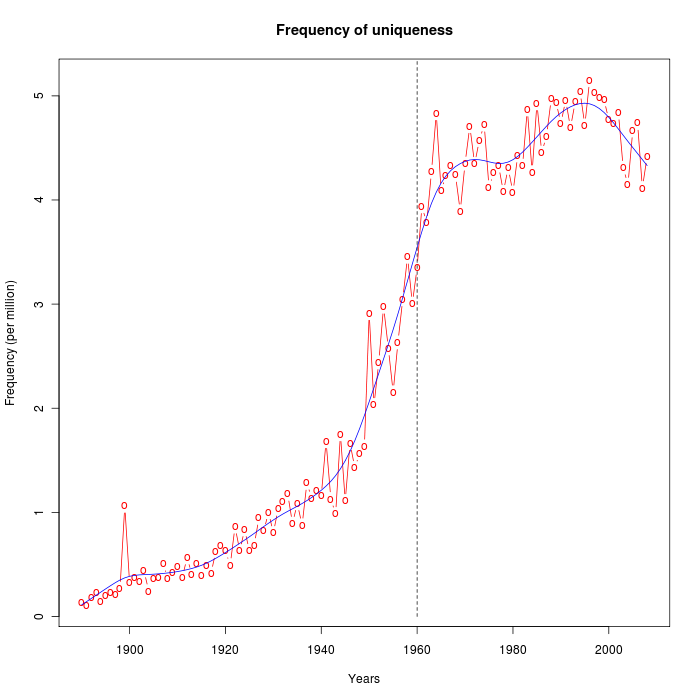

If we look at the particular words cited in that quote, again broadening the view to the period 1890-2008, the claim is sort of true:

|

|

But again, the description seems to be missing some interesting things. Thus "self" started to increase rapidly in frequency around 1940, not 1960; and it peaked in 1996. And "uniqueness" increased steadily from 1890 onwards, with a rapid rise from 1945 to 1965, and a relatively flat trajectory since then.

What's really going on here? The numbers involved are very large, and the changes are relatively smooth and extend over relatively large ranges of both absolute and relative frequency, so that it's quite clear that these time series are not just noise. But what kinds of signal are really involved? Here are a few possibilities:

- The mix of kinds of books published changes over time (e.g. more romance novels, fewer collections of sermons); different kinds of books use words differently; therefore the relative frequency of words changes.

- The mix of kinds of books selected for the Google Books ngram collections changes over time; so the relative frequency of words changes, for similar reasons as in (1).

- The distribution of concepts or conceptual frames changes over time, even in the same sorts of books.

- The choice of words to express a given concept (in published books) changes over time, even in the same sorts of books.

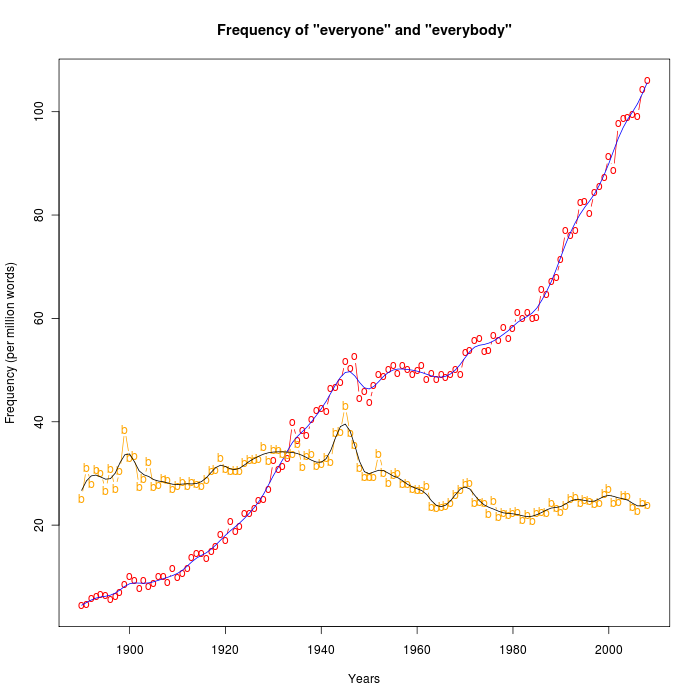

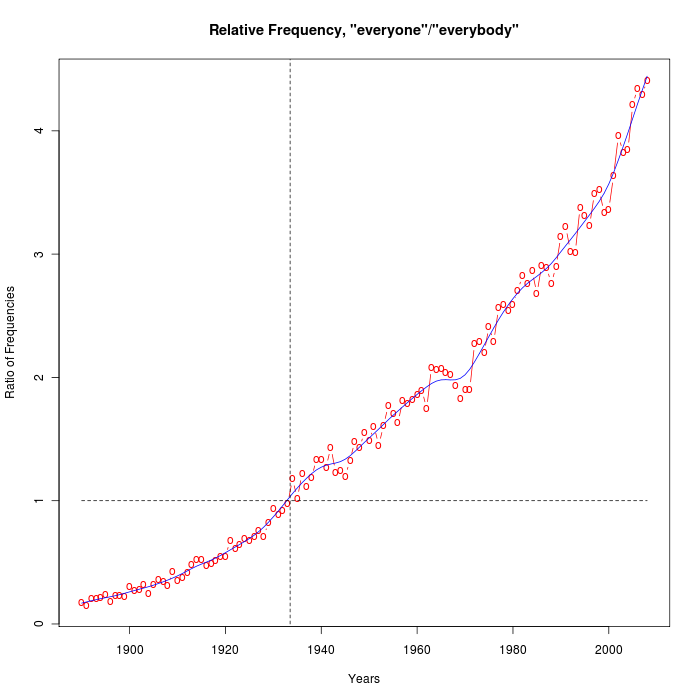

I have no doubt that all of these things are contributing to the time series that we see. As an illustration of point (4) — perhaps with a bit of a contribution from points (1) and (2) — consider the history of "everyone" vs. "everybody". As far as I can tell, these two words are universally inter-substitutable — there's no context (metalanguage aside) where the choice makes other than a stylistic difference. But the frequency of "everyone" (in the Google Books American English dataset) has been increasing steadily since the start of the 20th century, with a pause from 1945 to 1975; the frequency of "everybody" has been relatively stable. As a result, the ratio of "everyone" to "everybody" in this sample has increased more than 20 times, with "everyone" overtaking "everybody" at some point in 1934:

|

|

Unfortunately, we don't have the information about the Google Books datasets that would allow us to directly unravel these factors. We don't know what the actual books involved are; we don't know the broader contexts of the words; we don't have anything except the string counts by years. At some point in the (I hope not-too-distant) future, we'll have an open historical collection that will make it plausible to explore these questions.

And the Twenge et al. study uses these counts in a largely mysterious way, making it even harder to evaluate their claims. In an earlier post, I complained that

[The Twenge et al.] study doesn't, as far as I can tell, provide access to its data! This is completely inexcusable, in my opinion — everything is based on two 20-by-49 tables of numbers, which could trivially have been put in the (digital-only) "paper", or (better) made available on line as separate files. ("Textual Narcissism", 7/13/2012)

And in a later post, I observed that Twenge et al. don't even provide the basic details required to make it possible to replicate their work by getting the numbers again from the Google Books ngram corpus, because

… the Google Books data does not collapse over case, so that e.g. "solo", "Solo", and "SOLO" are all distinct items. I counted only the all-lower-case versions of the words; they don't say what they did. ("What does this graph mean?", 7/15/2012)

At the time, I thought that this last point didn't matter a great deal, since for most words, the lower-case and case-independent counts are close being proportional, year by year, e.g.

|

|

But there are a few words their lists that behave quite differently. If you look at the lists and think about it a bit, you'll see what (at least some of) words are.

Their 20 "communal" words: communal, community, commune, unity, communitarian, united, teamwork, team, collective, village, tribe, collectivization, group, collectivism, everyone, family, share, socialism, tribal, union

Their 20 "individualistic" words: independent, individual, individually, unique, uniqueness, self, independence, oneself, soloist, identity, personalized, solo, solitary, personalize, loner, standout, single, personal, sole, singularity

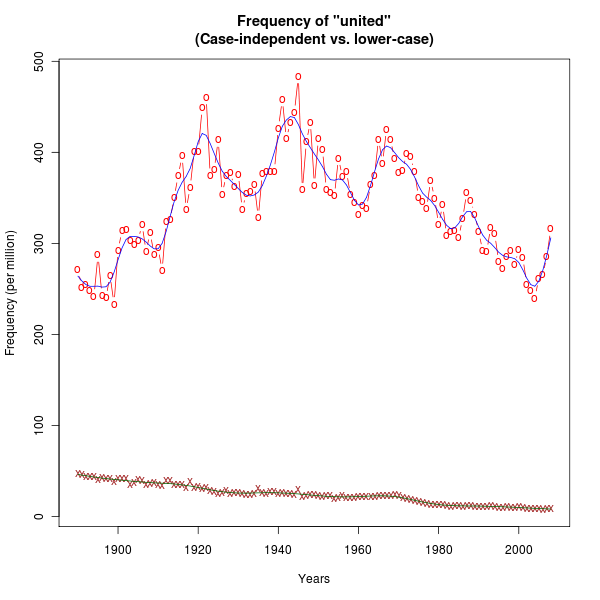

A large fraction of the instances of the word "united" are in proper nouns ("United States", "United Kingdom", "United Nations", "United Airlines", etc.), and are therefore capitalized. As a result, the time series of lower-case and case-independent frequency are very different:

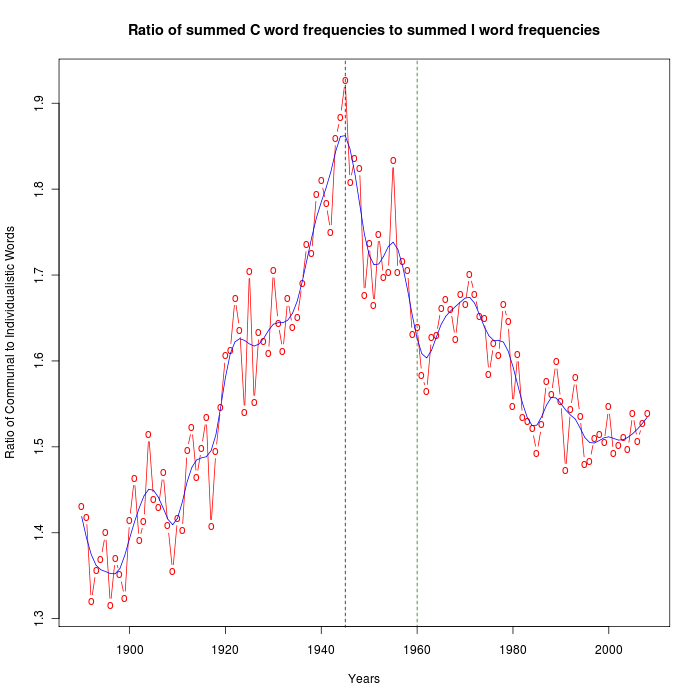

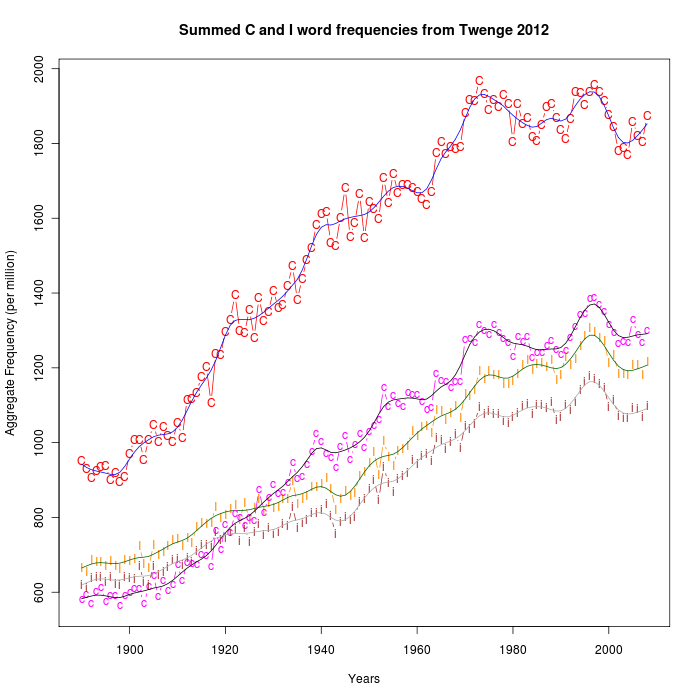

Something similar is true for "union", and to a lesser extent for some other words as well. As a result, the case-independent aggregate counts show a much bigger difference between "communal" and "individualistic" words than the lower-case-only counts do:

And as further result, the ratios of the aggregate counts behave somewhat differently in the post-WWII era:

|

|

(Note that their paper deals only with the changes over the period 1960-2008 — thus missing what might be the most interesting aspect of these numbers, namely the large difference between the behavior of these aggregate frequency ratios before WWII and after WWII.)

In my opinion, the relative frequency of proper nouns like "United States" and "United Kingdom" is not likely to tell us very much about whether "language in American books has become increasingly focused on the self and uniqueness", and so I suspect that the lower-case-only data is more relevant to the issues that Twenge et al. raise. But given this (in retrospect obvious) problem with their word lists, it's all the more unfortunate that they provide neither the table of data that they used, nor a recipe for calculating it from the original (publicly available) source. Instead, they give us only regression coefficients and significance levels.

Anyhow, I continue to think that the numbers in the Google Books datasets are fascinating. I just wish I had a clue as to what they mean.

[Note: I'll provide a link to the data and code a bit later today — some clean-up is needed, and I've run out of time for this morning's Breakfast Experiment™.]

Update — the data is here.

Sivi said,

July 31, 2012 @ 8:03 am

Even if their word counts, post-1960, were true, and there were significant increases in 1st-person singular pronouns and "individualistic" words over 1st-person plural pronouns and "communal" words, in a way that was strikingly different from earlier trends, it seems to me that they'd still have to show that this meaningfully reflects social behaviour or cultural shifts, rather than simply reflecting changes in word usage or writing styles.

[(myl) In some cases, the changes in word frequency certainly do reflect changes in underlying social, political, cultural, or economic realities — see e.g. the "Culturomics" paper for several convincing examples. And in other cases (e.g. the changes in everyone vs. everybody) the change seems to be purely a matter of lexical fashion. If we had access to the underlying books and their metadata, we could explore the nature of the effects empirically in uncertain or mixed cases.]

david said,

July 31, 2012 @ 11:13 am

The google ngram machine shows a fairly steady decline in the presence of "thee" from 1800 to 1997 and then asurprising upturn, with the 2008 value about six times the 1997 value.

Mary Kuhner said,

July 31, 2012 @ 11:18 am

It seems clear that if people start to talk about X more, that means X is more salient to them than it was before. But it's not at all clear that that X is more accepted or popular. It might be that all of the mentions are in the context of criticism or denunciation.

As a recently charged example, if the data were split up by geographic location, you could ask whether abortion is mentioned more often in US or European texts. I believe you would find that it's mentioned more often in the US; and that would be a very poor predictor of the societal acceptability of abortion.

So, a huge upswing in words expressing individualism could be in the context of an upswing in individualism, or an upswing in criticism of individualism, and I don't see how word counts alone could tell you.

[(myl) What you say is absolutely correct, in the abstract. But just to keep the concrete facts on the table: (1) There is no "huge upswing in words expressing individualism" — in the lower-case unigram data for the 20 "communual" and 20 "individualistic" words cited in the Twenge et al. paper, there's essentially no change between 1960 and 2008 in the ratio of aggregate frequencies; (2) There are at least two other possibilities to keep in mind with respect to changes in relative frequencies, in cases where such changes do exist — there might be an artefactual change in the mix of books in the collection from year to year, or their might be a change in the relative frequency of common word uses that have nothing to do with with the concepts under study, such as "United States" or "filet of sole".]

I think this is particularly likely for "union". The capitalized form seems likely to appear in US criticism of the Soviet Union, at least until recently; the lower-case form often appears in criticisms of labor unions; it's very hard to say that people using the word "union" are expressing a communitarian spirit at all.

Philip Spaelti said,

July 31, 2012 @ 11:33 am

I have a different kind of question about such n-gram searches. A corpus like the Google corpus is presumably created by large-scale OCR, and is probably not carefully proofread. In my experience words containing certain types of letters are more likely to be mangled by the OCR process. At what point do such errors begin to affect the word counts? (To take a simplistic example "I" might be much more frequently mis-read (as "1", "l", "i", and so on) than "you."

[(myl) Again, without access to the underlying collection of books, it's not possible to answer this question with any precision. My impression is that the overall rate of OCR errors in most English-language material published since 1890 is relatively low, especially in plain text (as opposed to indexes and so on). ]

Bloix said,

July 31, 2012 @ 11:38 am

A couple of changes that might not be significant enough to move the needle:

1) There's been a relaxation in the journalistic and convention that barred an author from admitting that he or she exists. One still sees this occasionally in the New Yorker but hardly anywhere else (an invented example would be, "'Yadda yadda,' he said to a companion," instead of "to me.")

2) The use of "one" instead of "you," as in (1) above, is almost entirely obsolete – "you still see this" has replaced "one still sees this."

chris said,

July 31, 2012 @ 4:11 pm

The capitalized form seems likely to appear in US criticism of the Soviet Union

Or discussion of the US Civil War. Talk about the Union could be either favorable to it or unfavorable to it (notwithstanding the old saw about who writes the history books), but it wasn't particularly more or less communalist than its opponent, the Confederacy, just because the latter's name didn't make their list.

"Sole" also jumps out for its polysemy (or should that be homography?) — if they can't make any attempt to distinguish the adjective from the fish from the part of a shoe, how can they possibly draw any useful conclusion whatsoever from a shift in the frequency of usage of the word, even if such a shift is proven?

[(myl) Without any time constraints, a search for "union" in Google Books (which unlike the ngram corpus executes a case-independent search) turns up in the first 10 hits: 4 mentions of the European Union, 2 mentions of the Soviet Union, one mention of the Union side in the U.S. Civil War, one mention of the Union Pacific, one mention of the Treaty of Union of 1707, and one mention of the Minneapolis Citizens Alliance, "a union of Minneapolis business owners in their campaign against organized labor".

In a search constrained to 1960, the first ten hits include 6 from issues of The Rotarian dealing with the question "Do unions have too much power?"; 1 ifrom The Crisis dealing with racial discrimination "among the skilled unions in the building trades", 1 from the Kenya Gazette dealing with "the Trade Unions Ordinance"; 1 from the ABA Journal dealing with "the Inter-Parliamentary Union" in Geneva; 1 from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists dealing with "the International Council of Scientific Unions" and its constituent unions of this and that.

In a search constrained to 2005, the first ten hits include 5 from the Kenya Gazette dealing with monetary unions, trade unions, customs unions, and the Kisii Farmers Union; 2 from Jet Magazine reference the actress Gabriel Union; 1 from Jet Magazine dealing with the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; 1 from American Cowboy dealing with the Cattle Growers Union of Chihuahua; 1 from Competition Science Vision referencing the Administrator of Chandigarh Union Territory]

William Steed said,

July 31, 2012 @ 5:51 pm

Another thing that might affect I vs. we ngrams is narrative style. If (as fiction publisher editors have complained [citation needed]) the number of fiction books written in the first person has increased over the last 100 years, that would produce a bias in the results. I am assuming here, that Google's ngram algorithms include fiction as well as non-fiction books.

Rubrick said,

July 31, 2012 @ 9:06 pm

What would it take to get you or one of your have-a-clue colleagues to publish a proper, well-researched journal article on this topic, demolishing Twenge and co.'s shoddy, agenda-driven work as it deserves to be demolished? Or would that just be spitting into the wind?

Andy Averill said,

July 31, 2012 @ 10:06 pm

The word "loner" jumped out at me from that list, since it seems like a word whose heyday began fairly recently, so I did a Google Books search going back to 1900.

In fact, there were only a small handful of occurrences before 1958, when it appears in a thesaurus called The Synonym Finder, which includes a lot of slang words. This suggests that it had been around for a while in oral English, but wasn't considered formal enough for use in publications. (The synonyms for "loner" are mostly pejorative, by the way.)

Nevertheless, between 1900 and 1958, "loner" appears something like 14,000 times in Google Books, but only as a surname (capitalized), or as an OCR mistake for "lower", "long", "longer", "lonely", and even "ioner" (the second half of "commissioner", split between two lines). Many of these occurrences were in passages of pure gibberish.

This didn't surprise me — I've often run across large quantities of gibberish while doing Google Books searches, especially in older books and serials. The question is, is the Ngram Viewer somehow able to filter out all the noise? Judging from the graph it displays for "loner", which shows plenty of (invalid) occurrences before the 50's, I suspect they don't do any filtering at all. (The graph shows a big climb after 1958, then levels off around 1985.)

Which raises the question — when people use the Ngram Viewer for published research, do they spot-check the results by hand to at least get a feeling for the quality of the data?

[(myl) The original work used to create the collections, supervised by Erez Lieberman and Jean-Baptiste Michel, made some serious attempts to filter out egregiously bad metadata and really horrible OCR. But in the cases of subsequent work, I haven't seen any recognition of the issues that you mention. In particular, Twenge et al. don't seem to have considered them.

FWIW, here are the plots for "loner" in the Google Ngrams American English collection:

]

Bert said,

August 1, 2012 @ 7:06 am

I'm with all those commenters that question the interpretation of this statistics (independently of wether the findings are real or not). In all of the cases where such a trend was seen (this study, President Obama vs. xyz, etc.), the authors seem to insinuate a trend in society or individuals towards being more egoistic. But this is in fact an open question, and you can only claim this to be true if you show a correlation between in a shift in word use and some psychological variable.

The only study I am aware of, which did this for "I, me, myself" (looking at the individual rather than society), is by Pennebaker and colleagues "Word Use in the Poetry of Suicidal and Nonsuicidal Poets"

http://www.psychosomaticmedicine.org/content/63/4/517.short

If you stick to this study, the trend towards "I" would imply that society has become more self-conscious, melancholic and suicide-prone – and not boasting a huge ego.

[(myl) Indeed — see Jamie Pennebaker's guest post here.

But there are two stages to such an argument:

(1) What are the numbers?

(2) What do such numbers mean?

The problem with the media meme about first-person-singular pronouns is threefold: first, there generally are no numbers; second, when we look into what the numbers are, they generally point in the opposite direction of the assertions by George Will, Stanley Fish, Peggy Noonan, and their colleagues; and third, such numbers probably don't bear the interpretation that they want to put on them, in any case.

The Twenge et al. article in PLoS One is much more serious. It's not about pronouns, — indeed they cite Pennebaker's work — but about words associated (according to a crowd-sourced word-association experiment) with the concepts "communal" and "individualistic". They then took some counts associated with these words from the Google Ngrams American English dataset, and did some statistical analysis purporting to show that

Unfortunately, they don't provide the data, beyond a reference to the published collection of datasets; and they don't tell us what they did about the case of letters. This matters, because if they allowed upper-case letters, then at least a quarter of their aggregate counts were associated with phrases like "United States" and "Soviet Union", whose frequency presumably has little or nothing to do with the socio-cultural concerns that they want to focus on.

In addition, the fact that their time span starts with 1960 means that they ignore the implication (of the frequencies in published books of their own wordlist) that "language in American books" was much more "focused on the self and uniqueness" in 1900 than 2008. I doubt that this implication is true, but in any case it spoils the whole "Generation Me" / "Narcissism Epidemic" vibe of Prof. Twenge's oeuvre.]

Justin S. said,

August 1, 2012 @ 7:36 pm

I can't replicate these results in COHA.

[(myl) Which results do you mean? Among those I've tried, some replicate and some don't. For one that more or less does replicate, here's the ratio of "everyone" to "everybody" by decade in COHA:

And in earlier posts (here and here) I showed that the pattern of aggregate "communal" vs. "individualistic" word frequencies is pretty well replicated in COHA.]