Pictish writing?

« previous post | next post »

According to Jennifer Viegas, "New Written Language of Ancient Scotland Discovered", Discovery News, 3/31/2010:

Once thought to be rock art, carved depictions of soldiers, horses and other figures are in fact part of a written language dating back to the Iron Age.

The ancestors of modern Scottish people left behind mysterious, carved stones that new research has just determined contain the written language of the Picts, an Iron Age society that existed in Scotland from 300 to 843.

The "new research" is described in Rob Lee, Philip Jonathan, and Pauline Ziman, "Pictish symbols revealed as a written language through application of Shannon entropy", Proceedings of the Royal Society A, in press.

The authors use an argument of the same general shape as the one used by Rao et al. in arguing for linguistic structure in inscriptions from the Indus Valley civilization ("Conditional entropy and the Indus Script", 4/26/2009). They calculate certain statistical measures for some known writing systems, for things that are clearly not writing, and for the inscriptions in question, and they find that in terms of these measures, the inscriptions look more like the writing sytems than like the non-writing sets.

The trouble with this form of argument is that it's heavily dependent on the particular combination of statistical measure and comparison sets that we choose. And the argument becomes especially unconvincing when there's an obvious alternative choice of comparison set — generated by a simple random process — that would fall squarely on the side of the line that allegedly identifies "written language".

That's what Cosma Shalizi, Richard Sproat and I (independently) argued in the case of the Rao et al. article (see here for details). And it looks to me as if the Lee et al. article on Pictish has got similar problems.

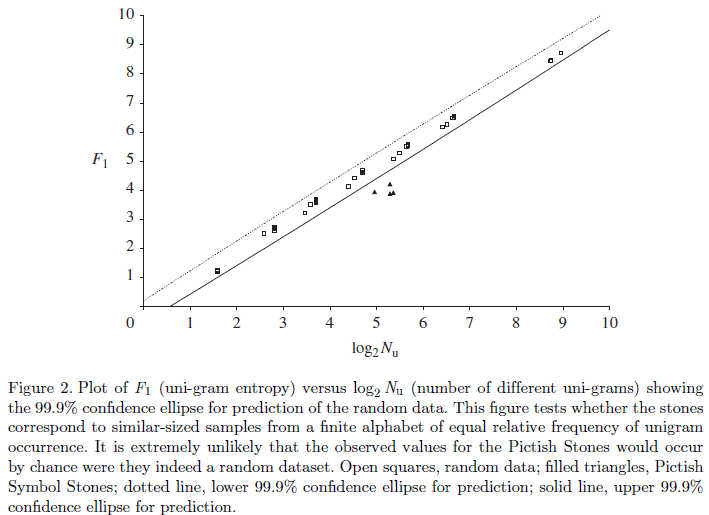

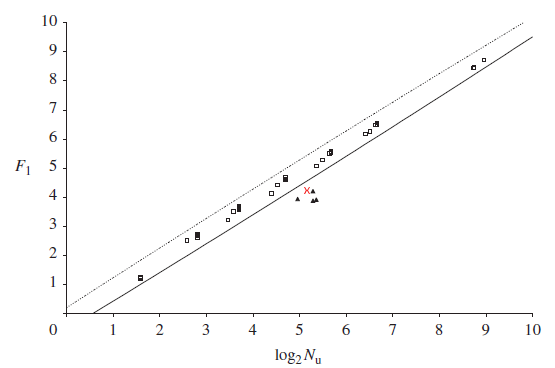

Let's take the first part of their argument, summarized in their Figure 2:

This shows convincingly that the Pictish petroglyph symbols are not drawn randomly from a uniform distribution. But symbols in writing systems are hardly the only phenomena whose statistical distribution is non-uniform. For example, if we plot the outcome of rolling 7 6-sided dice on the same graph, we get the red x shown below:

There are 36 possible outcomes (sums from 7 to 42), so that the x-axis value for the dice will be log2(36), or about 5.17. And these outcomes are not equally likely, since there's only one way to roll 7, but 7 ways to roll 8, 28 ways to roll 9, etc. — so if we calculate the entropy of the 36 probabilities, we get about 4.22.

I certainly don't mean to suggest that the ancient Picts generated their petroglyphs using throws of 7d6. The point is just that any process that is (in effect) sampling from a distribution with the right number of alternative outcomes (about 35 to 40) and the right amount of non-uniformity (around 20% relative redundancy for unigrams) will look similar on this measure. And we don't need to look very far to find a (non-writing-related) random process with these characteristics.

Lee et al. go on to repeat the same form of argument using a number of more sophisticated (or at least more complicated) measures. I haven't evaluated these in detail. But the way that they present Fig. 2 is not a good sign, in my opinion.

Mark P said,

April 2, 2010 @ 11:42 am

Might there be other avenues to look for evidence about this? It seems at least possible that the memory or record of a written language might not disappear completely. For example, is there anything from Roman times indicating the existence of a written language in Scotland? Folk tales? I also wonder how American Indian pictograms (such as the ones done by Indians about historical events in the 1800s), which were meant to tell a story but which are not a written language, would fare.

Rubrick said,

April 2, 2010 @ 2:43 pm

I certainly don't mean to suggest that the ancient Picts generated their petroglyphs using throws of 7d6.

Of course not. Picts have a to-write roll of 1d20 (against Intelligence), modified by the AC of the rock. A natural 0 used to be an automatic typo, but I think they changed that in 4th edition.

Nathan Myers said,

April 2, 2010 @ 2:45 pm

Whatever pens they may have had, they turned out not to be mightier than swords.

Topherclay said,

April 2, 2010 @ 4:35 pm

Rubrick, there are no zeros on a twenty sided die. You mean to say a natural one, and no one plays fourth edition anyway.

David B Solnit said,

April 2, 2010 @ 4:45 pm

Don't overlook this quote from the article:Lee explained that writing comes in two basic forms: lexigraphic writing that is based on speech and semasiography, which is not based on speech… "In semasiography, the symbols do not represent speech — such as the cartoon symbols used to show you how to build a flat pack piece of furniture — and generally do not come in a linear manner."

First of all, if it doesn't represent speech, I for one wouldn't call it writing. Second, if it doesn't represent speech, the article's headline reference to "written language" is simply wrong. Of course there are plenty of metaphorical usages like "the language of gemstones," but the article pretty clearly does not intend that kind of reading.

David B Solnit said,

April 2, 2010 @ 4:46 pm

Oops, my attempt at a block quote failed.

How about

"Lee explained that writing comes in two basic forms: lexigraphic writing that is based on speech and semasiography, which is not based on speech… 'In semasiography, the symbols do not represent speech — such as the cartoon symbols used to show you how to build a flat pack piece of furniture — and generally do not come in a linear manner.'"

uberVU - social comments said,

April 2, 2010 @ 5:43 pm

Social comments and analytics for this post…

This post was mentioned on Twitter by languagelog: Pictish writing?: According to Jennifer Viegas, "New Written Language of Ancient Scotland Discovered", Discovery N… http://bit.ly/aM3G8y…

Heidi Kent said,

April 2, 2010 @ 5:58 pm

One might also consider running the same sort of analysis on the images found on a given set of totem poles, which might be a useful basis of statistical comparison if we know the function of the iconic elements (for example, mnemonic storytelling devices — not a language per se, but an organizing principle for the elements nonetheless). This might give a baseline for comparison of something between "some known writing systems, for things that are clearly not writing, and for the inscriptions in question."

[(myl) Lee et al. included heraldic "sematograms", geneological lists, and so on in their (further) analyses.]

Richard Sproat said,

April 2, 2010 @ 7:05 pm

David Solnit identifies a key problem with all of these attempts to prove that various ancient symbols were "writing". It's pretty clear that the authors, which includes Rao and his colleagues for the Indus stuff, and Lee and colleagues for this new paper, don't really seem to understand what it means for a symbol system to represent language — i.e. be writing.

Any real writing system can be used to write down anything one might choose to speak. Is the Pictish system supposed to be like that? Well, putting aside the issue of whether in fact the statistical methods demonstrate anything at all, and taking at face value their conclusion that "that the Pictish symbols are very constrained words, similar in constraint to the genealogical name lists", that begs the question of what this phrase actually means.

There are no true writing systems based completely on logography — simply because it's too impractical to use a symbol set that requires rote memorization of tens of thousands fo symbols. (No, Chinese does NOT work that way…) Furthermore the Pict symbol set is fairly small, suggesting that it must indeed have been constrained to represent very few words. Well they do say it's similar to genealogical name lists, and given the symbols' function on standing stones, and given the extreme brevity of the texts ("the often short nature of individual inscriptions [one to three symbols in length]"), let's suppose that's what they were. So maybe they mean something like what the Ogham stones often meant, things like "X son of Y". So maybe the symbols represent individuals. Problem is, we get into an issue of definition here. I can represent things like "X son of Y" by juxtaposing two photos of the people concerned, with maybe some sort of connector symbol to indicate the "son of" relation. But is that "language"? I certainly can *read* it if I want to. But then I can also "read", say, tarot cards or mathematical formulae. It seems to me that even if you can show (and I am of course not arguing they do show this) that the symbols can encode the kinds of things one might say using language, it doesn't mean they are language. Such symbol systems *may* evolve into full writing systems, as was the case with the evolution of Sumerian writing from an ancient token system for representing commodities. But until it can be demonstrated that anything one might say in Pictish could be written using these symbols, it doesn't seem to me it would count as language.

Richard Sproat said,

April 2, 2010 @ 10:42 pm

To put the above point more succinctly, I observed a version of the sign below outside my apartment (but without the words "bus stop")

http://www.nzta.govt.nz/resources/traffic-control-devices-manual/sign-specifications/images/p03-02-01.gif

I found myself "reading" it as "no parking, bus stop". I guess this is "language", and therefore these symbols must be "writing".

Stuart Clayton said,

April 3, 2010 @ 1:17 am

I agree with Mark that the statistical arguments deployed by Lee et al. seem unconvincing. As a quasi-mathematician familiar with some basic information theory, I would like to add my own two cents' worth on their paper. My approach is that of the concert-goer who, bored by the musical performance, begins to study the programm leaflet and cast sideways glances at people near him in the audience. That is, since I can't follow the arguments, I turn my attention to the appearances.

The mathematics used by the authors is basic information theory stuff, but presented in such a confused fashion as might seem non-trivial to non-mathematicians, but definitely annoying to mathematicians. In other words, the paper seems designed to impress rather than convince – even if the authors are only impressing themselves. Essentially, it impresses by a combination of hand-waving and apparent user-friendliness. The tactic used there is familiar from Wikipedia articles: define "the basics" in apparently simple words, and take it from there, piling on more and more simple words. A self-contained paper, with everything the autodidact needs !

The authors briefly explain first-order entropy F1 (page 4), but already at the end of the paragraph I'm boggling. What kind of reader, expected to understand the whole paper, needs to be told the following, confused as it is?:

That last sentence makes my mind reel. Anything that is non-random is characteristic of writing ?? There is a similar conceptual boggler at the bottom of page 2:

On this argument, a geometrically patterned frieze would be a "communication".

The authors' explanation of first-order entropy contains this: "… the relative frequency of a character calculated from the dataset. In a large dataset, set of random characters (i.e. sampled with equal probability from a finite lexicon), all uni-grams appear with the same frequency". But what is the meaning of "sampled with equal probability" ? The frequencies with which characters occur in a text is determined by counting their occurrences, as the (tag end of the) first sentence quoted says. There is no sampling involved. Suppose the character frequencies in a text are not all the same. How could they suddenly become characters "appearing with the same frequency", due to "sampling" ? What is the significance of "large" dataset here ? Do the authors think that "random" and "equal probability" somehow mean the same thing ?

The authors' explanation here is so confused that any attempt to clear up the confusion is likely to sound just as confused. At any rate that's the feeling I've just gotten. The easiest solution would be to direct the reader to a good textbook, where she can start from scratch. I recommend Henri Atlan's L'organisation biologique et la théorie de l'information.

Whatever the cash value of the authors' arguments may turn out to be, their presentation doesn't incline me to extend them any credit.

Stuart Clayton said,

April 3, 2010 @ 1:20 am

What a pity. The formatting I had in place for quotes for the paper appeared as intended in the preview, but vanished in the published comment.

[(myl) WordPress (or at least our installation of it) is annoying that way. I've made an attempt to restore (some of?) the formatting you intended — if you'll send me a note about what you really wanted, I'll try to add it in ways that WordPress won't destroy.]

Pavel Iosad said,

April 3, 2010 @ 4:07 am

I have not yet seen the paper, but the interview quoted is sometimes hilarious. Apparently the Picts did not only have written language, but (as if someone thought the contrary) also a complex spoken language. You don't say!

In any case, this all seems like a case of looking for something in a lighted place, as opposed to where you lost it. It would be much more interesting if someone tried doing something like this with the "nonsense" Ogham inscriptions. That is, we know that some "Picts" (where "Picts" is of course pretty much a cover term for "any tribes living north of the Brigantes and Votadini, the northernmost tribes that Romans knew relatively much about") spoke a Celtic, in all probability a Brythonic language, and some "Picts" spoke a different language, often assumed to be non-IE. This latter is recoverable from placenames and personal names, but the tantalizing issue is a number of Ogham inscriptions which are not in Goidelic Celtic and have yet defied convincing decipherment. To look for a language in, uh, pictures, when there are possibly two perfectly "normal" languages in the same place strikes me as, let's put it mildly, fruitless.

Stuart Clayton said,

April 3, 2010 @ 5:39 am

Thanks for reviving the formatting. Everything is now just as I intended it.

Terry Collmann said,

April 3, 2010 @ 10:31 am

And just a minor point from the Discovery News report on this: the Picts are not, or rather, not the only people who are "the ancestors of modern Scottish people": modern Scottish people are also descended from Angles, Britons, Irish (the 'real' Scots) and Vikings. Plus a few Anglo-Normans.

Trond Engen said,

April 3, 2010 @ 10:58 am

Thanks, Stuart. You put words to my own experience. Every time I read through it the vital parts seemed to elude me. I long thought it was my holiday self being unable to focus, but finally last night I gave up on it.

So why did I even bother with such obvious lack of understanding of what constitutes language? Because I hoped for something interesting in there, like a first approximation to useful statistical characteristics. Or at least an idea of what the authors concider useful characteristics. But it seems not.

Richard Sproat said,

April 3, 2010 @ 3:37 pm

In response to Stuart Clayton's question: yes I think they DO think that "random" and "equal probability" somehow mean the same thing. This is a common misunderstanding in work in this area: the Rao et al. paper on the Indus stuff made the same mistake.

Nijma said,

April 3, 2010 @ 9:40 pm

I'm no linguist, but this immediately struck me as bogus. I have no idea why I couldn’t take this theory seriously; it's sort of like picking up an antique and deciding by the feel that it’s a reproduction.

It seems the whole Rao/Lee/Markov analysis is about what symbol follows what in an inscription, and yet these stones have typically only one or two symbols. How can you possibly apply a theory about a chain of events to something with one event? So that’s one thing that bothers me.

The Pictish stones don’t really qualify as “very short sequences of regularly placed symbols”. If you look at the Indus inscriptions, they have a large picture and a series of smaller symbols one after another that actually look like writing. The symbols on the Pictish stones that I pulled up from the University of Strathclyde database

http://www.stams.strath.ac.uk/research/pictish/database.php

were placed irregularly, and I thought rather decoratively across the stone. So that’s another thing that bothers me.

Then, the statistics. In the applications I’m familiar with, for a statistically significant result, you need a sample size around 1000, although that’s still rather smallish. The Pictish stones have what, 30 some samples of symbols across a few hundred monuments?

The Pictish stones look to me like they have more in common with Viking monument stones, for which there is a known written language.

marie-lucie said,

April 4, 2010 @ 2:38 pm

I looked at some of the stones in tne Pictish database (thank you, Nijma). One of them includes an Ogham inscription along one vertical edge. I cannot read Ogham, but it is a true alphabet and the inscription can therefore be read by a competent person. Other designs are not "writing".

Richard Sproat said,

April 4, 2010 @ 4:12 pm

I would hazard a guess than any Ogham inscriptions on such stones postdate the Pictish symbols.

Richard Sproat said,

April 4, 2010 @ 4:57 pm

Extending Mark's experiment to their Figure 5, I built a corpus of "text" for 1000 individual events of 7 tosses of a 6-sided die. I computed their Nd/Nu (the number of observed bigram types divided by the number of unigram types — which they term "degree of di-gram lexicon completeness") and Sd/Td (number of bigrams that occur once divided by the total number of bigrams — what computational linguists know as n1/N or the Good-Turing measure of the probability of an unseen event — which they call degree of digram repetition.

I get the following values:

Nd/Nu = 12.56

Sd/Td = 0.13

The figure below shows this superimposed as a red square on their plot:

http://www.cslu.ogi.edu/~sproatr/newindex/pictish.png

Another run has Nd/Nu = 12.59 and Sd/Td = 0.12, so that the square would be somewhat lower.

From this result, and consulting their caption below the plot, we can conclude that 7d6 is probably a writing system consisting of letters.

marie-lucie said,

April 4, 2010 @ 9:49 pm

RS: I would hazard a guess than any Ogham inscriptions on such stones postdate the Pictish symbols.

This occurred to me too, but the fact that a true written inscription was added to the designs (whether at the time of carving them, or later) seems to imply that the designs are not themselves a type of writing. I did not have time to look at all the stones in the database, but I still saw a fair number of them, and the Ogham only occurred once. A person competent to read the Ogham should be able to tell whether the inscription is in a known form of Old Celtic or in a different language.

Richard Sproat said,

April 5, 2010 @ 11:51 am

I wouldn't necessarily conclude that. After all, palimpsests occur on many media. Quite possibly whoever carved the ogham inscription found the particular stone in question handy for that purpose, much as modern graffiti writers find subway cars handy for their purpose.

marie-lucie said,

April 5, 2010 @ 12:46 pm

All right.

Stuart Clayton said,

April 5, 2010 @ 2:01 pm

Well, and here I had thought it would be stupidly facetious to suggest such a thing at such a site. My idea was that the Ogham might be some kind of scholarly or administrative gloss, such as "already anticipated by Gilgamesh" or "duplicate copy, can be discarded".

Richard Sproat said,

April 5, 2010 @ 3:02 pm

I assume the Ogham one Marie-Lucie is referring to is this one:

http://www.stams.strath.ac.uk/research/pictish/database.php?details=7

I can't make any sense of it as Celtic, but maybe I'm reading it wrong.

marie-lucie said,

April 5, 2010 @ 3:08 pm

Have fun if you like, but if the Ogham has been added at a later date, it more likely reinforces the meaning of the design on the stone, perhaps adding a name or some such. Those stones are hard to carve, otherwise the designs would have become eroded over the centuries (there are examples in the database). I don't believe that the Ogham inscription in this one case is mere graffiti.

marie-lucie said,

April 5, 2010 @ 3:15 pm

RS: Actually, no, it is another one, which I am too lazy to try to find at the moment. The one I am referring to, as I said, has a vertical baseline and looks more expertly carved. The one you found does look more like graffiti, carved in a softer stone. I had not seen it, but I had not looked at all of them, as I said earlier. (I started at the top of the list, had to stop, and started later from the bottom of the list, but missed the middle part).

Richard Sproat said,

April 5, 2010 @ 4:00 pm

If you can find the one you are referring to I may be able to tell if it's Celtic.

Richard Sproat said,

April 5, 2010 @ 4:02 pm

Sorry but I don't see the reasoning behind your remark Marie-Lucie:

"if the Ogham has been added at a later date, it more likely reinforces the meaning of the design on the stone, perhaps adding a name or some such. Those stones are hard to carve, otherwise the designs would have become eroded over the centuries (there are examples in the database). I don't believe that the Ogham inscription in this one case is mere graffiti."

Ogham inscriptions were frequently of the form "X son of Y", and why could someone not have just used this stone as a convenient place to carve such an inscription?

marie-lucie said,

April 5, 2010 @ 6:09 pm

RS: Perhaps we don't have the same definition of "graffiti". To me it is something done idly, like "X was here" by tourists on Greek columns, or fast, like writing "Yankee go home" on a wall, or scurrilous verse in a bathhouse in Pompeii, etc. It seems to me that taking up the tools to carve a hard stone is not something that can be done lightly, especially in a society where few were likely to be literate.

Anyway, I just looked at the entire series, and there are more Ogham inscriptions than I thought. I will just tell you the locations, in alphabetical order: Ackergill 1 (Keiss Bar) is the one you found; Bransbutt (Inverurie) is the one I had noticed, which is also the clearest one; Formaston (Aboyne); Lang Stane (Fetteresso); Latheron 1. Besides, there are two inscriptions which seem to have Ogham strokes along a circle or curve rather than a straight line: Dyce 2, and Logie Elphinstone 2.

Perhaps you can make sense of some of these inscriptions.

Besides the ogham, there are a few examples of Pictish inscriptions which are more similar to writing (and they are not on the monumental stones): Dunicaer 1, 4 and 6, and in two of the East Wemyss Caves: Dovecot, and Jonathan (2 examples).

Richard Sproat said,

April 5, 2010 @ 6:29 pm

Perhaps I should have avoided the term "graffiti". But in any case, there's plenty of graffiti on rock faces, so it's possible to find things that are "idly" done that still require effort.

Anyway I just caution against reading too much into the occurrence of these Ogham inscriptions on these stones.

Richard Sproat said,

April 5, 2010 @ 7:11 pm

For anyone whose interested, I have extracted the Strathclyde data with their labels for the symbols into a CSV database:

http://www.cslu.ogi.edu/~sproatr/newindex/pict.csv

Richard Sproat said,

April 5, 2010 @ 7:12 pm

Oops, how about "who's" instead of "whose"…

marie-lucie said,

April 5, 2010 @ 10:28 pm

Let us know if you can translate the Ogham inscriptions.

Richard Sproat said,

April 5, 2010 @ 11:58 pm

I looked at a couple and they seemed to be nonsense, suggesting that:

1) They are not Celtic, or

2) That they are not any language, maybe pseudowriting (not unheard of with Ogham in Pictish inscriptions), or

3) I'm doing something wrong

Richard Sproat said,

April 6, 2010 @ 12:02 am

By the way the Wikipedia page on Ogham (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ogham_inscription) has a Pictish example, which claims to be for Bransbutt but doesn't correspond to the text on the stone shown in the Strathclyde database:

᚛ᚔᚏᚐᚈᚐᚇᚇᚑᚐᚏᚓᚅᚄ᚜

IRATADDOARENS[

(I love the fact that this works in Unicode…)

Ken Brown said,

April 7, 2010 @ 1:43 pm

marie-lucie said: "It seems to me that taking up the tools to carve a hard stone is not something that can be done lightly, especially in a society where few were likely to be literate."

Evidence on Stonehenge, Hadrian's Wall, and hundreds of early mediaeval parish churches in England, would seem to contradict that.

marie-lucie said,

April 7, 2010 @ 8:34 pm

You guys seem to know best.

About Pictish "pseudowriting", could those inscriptions just be in a non-Celtic language? or graffiti done by illiterates? Apparently there are conflicting opinions about how to interpret some of the "Pictish" Ogham inscriptions.

Aaron Davies said,

April 7, 2010 @ 10:50 pm

any politics (scottish separatism??) involved in this? istr reading (probably at amaravati) that a major driver of indus/harappan "language" scholarship is various indian and/or pakistani political issues. of course, this is generally secondary to the popular (and media) obsession with "decipherment" that has plagued the subject since champollion…

Nijma said,

April 8, 2010 @ 1:21 pm

Has anyone seen this interpretation of Pictish stones from 1888?

http://www.archive.org/stream/oghaminscription00ferguoft#page/132/mode/2up

Two stones were identified as Old Norse; religious themes or historical names were identified in others, and the difficulty in reading the inscriptions attributed to ecclesiastical pedantry. Themes of drawings that accompanied the oghams were identified, some as the Wild Hunt, others as Christian and similar to carvings in European churches.

Rajesh Rao said,

April 9, 2010 @ 1:22 am

Given the continued discussion of our work in this blog, the following article may be of interest:

http://www.cs.washington.edu/homes/rao/ieeeIndus.pdf

Note especially Fig. 3 which extends the conditional entropy result in our Science paper to block entropies for blocks of up to 6 symbols. A similar result using a different technique is in: A.O. Schmitt and H. Herzel, “Estimating the entropy of DNA sequences,” J. Theor. Biol., Oct. 1997, pp. 369-377.

Please also read the discussion of how to interpret the entropy result in the section "The language question and entropic analysis" in the above article.

Links to our other papers published in PNAS and PLOS One, as well as our response to earlier discussions of the Science paper can be found at:

http://www.cs.washington.edu/homes/rao/indus.html

ohwilleke said,

April 12, 2010 @ 5:37 pm

The rub is that we know that neither the Picts nor the Indus Valley River civilization was using symbols randomly. The size of the symbol set, and the context in which they are written, and the fact that they appear in some sort of structure and are not obviously representational says a lot. The statistical analysis, together with the other coroborative evidence, suggests that these symbols were intended to convey abstract meanings in an organized way. If one if going to argue that its wrong, one needs to have a counterexplaination that makes sense given the total picture.

There are lots of written languages that weren't used to encode very rich literary information. The earliest Sumerian and Linear B writings are basically accounting or tax records, property brands, and in the Sumerian case, king lists, for example. Pictish symbols may not be able to tell us if the language was ergative or not, for example, or what it sounded like. It might not even have written verbs or have just one or two of them (begat; "is" implied). Simply discovering if the symbols were sound oriented or meaning oriented or a mix of both, or the basic nature of what is described, would be progress. Similarly, being able to rule out an encoding of a Celtic language would be very valueable.

Copying of symbols from Ogham, in a way that was clearly not encoding the same language as Ogham, would similarly shows both an intent to borrow for language related purposes (as many Native American tribes did without fully understanding the underlying system copied) and tells us something about the timing and nature of the relationship between Ogham and non-Ogham Picts.

Statistics isn't going to do a translation. But, it might be immensely helpful when an otherwise obscure clue surfaces.

Richard Sproat said,

April 14, 2010 @ 4:14 pm

So to summarize, if something isn't obviously representational (coz we don't happen to know what the symbols mean) and shows some structure (therefore seems to be trying to convey *something*), the best guess is that it is some sort of linguistic script.

That seems to be the crux of this and many similar arguments.

Sorry if I remain unconvinced.

Of course in any case one needs to have a measure that actually tells you you have structure. Conditional entropy is not such a measure, as I think has been amply shown in an earlier thread here, and elsewhere (e.g. my invited talk at EMNLP, which one can access online if one is interested).

Rajesh Rao said,

April 19, 2010 @ 12:22 am

One starts with a system that exhibits language-like structure and uses entropic measures to quantify this structure, not the other way around. As an example, consider the following facts about the Indus script:

• The Indus texts are linearly written, like the vast majority of linguistic scripts (and unlike nonlinguistic systems such as medieval heraldry or traffic signs),

• Indus symbols are often modified by the addition of specific sets of marks over, around, or inside a symbol. Multiple symbols are sometimes combined (“ligatured”) to form a single glyph. This is similar to other linguistic scripts, including later Indian scripts which use ligatures and marks above, below, or around a symbol to modify the sound of a root consonant or vowel symbol;

• The script obeys the Zipf-Mandelbrot law, a power-law distribution on ranked data, which is often considered a necessary (though not sufficient) condition for language;

• The script exhibits rich syntactic structure such as the clear presence of beginners and enders with asymmetric distribution, preferences of symbol clusters for particular positions within texts, etc., not unlike linguistic sequences;

• Indus texts that have been discovered in Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf use the same signs as texts found in the Indus region but alter their ordering, suggesting that the script was versatile enough to represent different content or a different language in foreign regions.

Given the above properties, consider the entropy scaling behavior exhibited by the Indus script in the following figure from the IEEE Computer paper in my previous post:

http://www.cs.washington.edu/homes/rao/IndusBlockEntropies.jpg

The language-like scaling behavior of block entropies in the above figure, in combination with the other properties of language enumerated above, could be viewed in a Bayesian framework as additional evidence for the linguistic nature of the Indus script.

Let us now consider the nonlinguistic systems that have been suggested.

Liberman, Sproat, and Shalizi in this blog constructed artificial examples of nonlinguistic systems whose conditional entropy was similar to the Indus script but their examples have no correlations between symbols – these examples do not exhibit the entropy scaling exhibited by the Indus script and languages in the above figure.

Medieval heraldry and traffic signs are not even linear, nor do they exhibit other script-like properties such as those listed above.

The Vinca markings on pottery are linear but scholars have established that the symbols do not appear to follow any order – the system thus can be expected to fall in the maximum entropy range (MaxEnt) in the above figure.

The carvings of deities on Mesopotamian boundary stones are also linear but the ordering of symbols is very rigid, following for example the hierarchical ordering of the deities. This system can be expected to fall in the minimum entropy (MinEnt) range in the above entropy scaling figure.

Sorry but if these are the natural nonlinguistic systems one can come up with, then I am yet to be convinced about the “collapse of the Indus-script thesis.”

Richard Sproat said,

April 20, 2010 @ 11:14 am

It is not true that the deity symbols on kudurrus are rigidly ordered. It's just not true. See

Ursula Seidl, Die Babylonischen Kudurru Reliefs.

You can check the book out from the University of Washington library, once I am done with it.

I built a small corpus of Mesopotamian deity symbols from kudurrus from Seidl's book. It's only about 500 symbols long but, hey, Lee et al's methods are supposed to work with small corpora. Of course it looks like writing given Lee et al's statistics.

As for Vinca symbols, it is similarly true that they are not random in their order. I really don't understand where these claims come from.

Until somebody has done the legwork of building a SERIOUS corpus of non-linguistic symbols of a variety of types, and has demonstrated a method that can distinguish these reliably from real writing, I will remain unconvinced. There are simply too many possible sources of structure in symbol systems to know yet that one has a method that can tell that the structure one observes is linguistic. Part of the problem is that most of the people discussing this in the press and on the blogs (this one excepted) know very little about either writing systems or symbol systems. There are non-linguistic systems like Naxi that will probably look like language if you did a statistical analysis since they are designed to allow one to tell stories — but are not writing systems in the normal sense.

At the end of the day, it is simply a fact that the basic requirements of scientific rigor have not been met. I continue to believe it's an interesting question whether one can distinguish linguistic from non-linguistic systems by statistical tests, but I do not believe that we have the answer to that question yet because the data do not exist to allow us to test it. Certainly we are not helped by papers that purport to demonstrate that such-and-such a system was writing, by providing a limited set of comparisons using tests that it is trivially easy to show don't test anything. That does not mean that such tests could not be devised, just that they haven't been yet.

Richard Sproat said,

April 20, 2010 @ 11:53 am

As for the other bullet items:

– Sure, the Indus symbols mostly appear linearly. So do lots of non-linguistic systems including Mesopotamian deity symbols, mathematical symbols, traffic signs (despite claims to the contrary, most traffic sign sequences I have seen are arranged in a linear fashion), and boy scout merit badges (which are usually arranged in neat rows and columns on a sash). Add to that Naxi, which is clearly non-linguistic on any clear definition of what it means to be linguistic.

– Ligaturing often occurs in non-linguistic systems. The Mesopotamian deity system ligatures what Seidl calls the "symbol base" with a variety of other symbols (it has a particular affinity for the "horn crown"). One sees ligatures in heraldry, if one allows that features like "langued" (having the tongue sticking out) or "armed" (showing talons) which are used with a variety of animal charges, count as diacritic elements (and on what basis would they not)? Plus one has to remember that until one knows how the system works (in the case of the Indus we do not), one cannot say with any certainty that a symbol that looks like a combination of other symbols is, in fact, a combination — as opposed to being a separate symbol. As any decipherer will tell you, one of the hardest tasks is figuring out what the basic symbol set is. For the Indus, one sees quite different proposals from Mahadevan, Parpola and Wells, all based on their differing assumptions as to what salient differences are.

Lots of things obey the Zipf-Mandelbrot law: heraldry, boy scout merit badges …

I'm a linguist, so when I think of rich syntactic structure I think of 30-word sentences with lots of embedded clauses. Given that the mean "text" length in the Indus system is about 4.5 glyphs, just how "rich" could it have been. In any case, non-linguistic systems also often exhibit rich structure: think mathematics, heraldry. In heraldry you get embeddings (via quartering) that go far beyond anything you see in language. And there are other constraints, such as the placement of certain symbols, constraints on placement of metals and colors, and so forth.

The Mesopotamian Indus texts may show different structures, but I'd be surprised if one didn't find the same thing within the Indus region proper, if one were to break down the corpus into regions and times. But in any event one finds differing structures in non-linguistic systems that are used over a sufficiently wide area: there are variations in heraldry across different countries. And one cannot rule out the possibility that the Mesopotamian texts were a result of someone using a system they didn't really understand. To give a linguistic example, the use of Chinese characters as decorative motifs by people who have no idea what they mean, and are only interested in how they look. Sometimes that results in contextually non-sensical "texts".

Rajesh Rao said,

April 22, 2010 @ 8:57 pm

Sure, one may cherry pick a system A that exhibits one language-like property and another system B that exhibits a different property but such an exercise misses the point. No one is claiming that a single property is sufficient to prove a system is linguistic. The reasoning is inductive. It is the confluence of a number of language-like properties in a single system (as in the case of the Indus script), combined with quantitative similarities to linguistic systems such as the entropy scaling in the figure above, that increases one’s confidence that the system may be linguistic.

Rajesh Rao said,

April 22, 2010 @ 9:02 pm

As for not knowing where the “claims” regarding the ordering of symbols in the Mesopotamian deity and Vinca systems are coming from, see:

J. Black and A. Green, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, 1992, British Museum Press, London. Page 114.

S. M. M. Winn, “A Neolithic Sign System in Southeastern Europe", in M. L. Foster, L. J. Botscharow, The Life of Symbols, Westview Press, Boulder, 1990. Pages 269-271.

Richard Sproat said,

April 22, 2010 @ 10:03 pm

We also cite those two sources in our 2004 paper. We seem to come to different conclusions as to what they say. Apparently there is no point in arguing about this since we are apparently going around in circles. Ursula Seidl's book has some nice data on deity symbols and it's pretty apparent from looking at that corpus that the system was not rigid. But there is no point in arguing this obviously.

Richard Sproat said,

April 22, 2010 @ 10:11 pm

I agree with one statement: no one property can tell us anything. In the case of conditional entropy or other such measures, that's really not the issue since the point is that nobody has done the exercise that needs to be done of comparing a bunch of real non-trivial ancient non-linguistic symbol systems with a bunch of real non-trivial linguistic systems. Only then can one say whether that measure (or some other measure) can even give us a bias towards the conclusion that such-and-such a system is linguistic. For all we know, conditional entropy could be entirely useless. Then it will be indicative of nothing and won't add to the list of other supposed language-like features.

Anyway this discussion is clearly getting nowhere.

‘Iron Age’ Picts and their spoken language « A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe said,

May 25, 2010 @ 9:30 am

[…] this is not without its problems even in its own terms, and as you might expect, Language Log has been all over them. The biggest problem is that the paper's random test set also comes out on the `written […]

Richard said,

January 5, 2012 @ 6:44 am

The answer is that the stones represent 15 festival days celebrated around 1160BC.