Non-Whorfian linguistic determinism

« previous post | next post »

I've been reading David Laitin's Politics, Language and Thought: The Somali Experience, which discusses a kind of linguistic determinism that (in my opinion) hasn't gotten the attention it deserves. So in keeping with my third annual New Year's resolution to emphasize positive blogging about linguistic issues, I'm going to tell you about some fascinating 35-year-old experiments described in Laitin's book, in the context of some more recent work on related issues.

I'll frame the discussion in terms of a deceptively simple question: do the results of public opinion polling depend on the language of the interview? The answer, it seems, is often "yes", and the effects are sometimes very large. This immediately raises a more difficult question: why?

For example, when Prof. Laitin's Somali assistants asked Somali-speaking students in the Northeastern Province of Kenya to complete the sentence "My favorite radio station is ___" (or its Somali translation), the answers varied as follows:

| Voice of Kenya | Somali Radio | BBC | |

| Asked in English (n=56) |

54% | 43% | 4% |

| Asked in Somali (n=70) |

24% | 51% | 24% |

When asked to complete the sentence "Between home and school, I prefer ___", their answers were:

| "Home" | "School" | |

| Asked in English (n=68) |

68% | 32% |

| Asked in Somali (n=71) |

25% | 75% |

These are obviously pretty large differences.

A similar issue came up in passing on this blog last summer, with respect to linguistic priming of responses in tasks intended to measure "individualism" vs. "collectivism" ("How to turn Americans into Asians (or vice versa)", 8/15/2008). In that post, I cited a review article by Daphna Oyserman and Spike Lee that gives "a meta-analysis of the individualism and collectivism priming literature" ("Does Culture Influence What and How We Think? Effects of Priming Individualism and Collectivism", Psychological Bulletin 134(2): 311-342, 2008). One of the priming methods that Oyserman and Lee discuss is the choice of language for conducting experiments among bilinguals.

According to the abstract,

Effect sizes [of priming] were moderate for relationality and cognition, small for self-concept and values, robust across priming methods and dependent variables, and consistent in direction and size with cross-national effects.

"Relationality" refers to "social obligation, perceived social support from others, social sensitivity, and prosocial orientation", as well as "more specific operationalizations such as the choice to sit closer to a target other".

"Cognition" refers to a wide variety of judgments, both social and non-social, that were among the dependent variables in the various studies that they surveyed. Many if not most of the questions asked in opinion polls would fall into this category (though of course this meta-analysis considered only test instruments deemed relevant to the individualism-collectivism dimension).

When they say that "effect sizes were moderate for relationality and cognition", they mean that priming changed these measures by about a half a standard deviation. (The actual range of effect sizes reported, for priming bilinguals by using one language or the other in administering the test, was -0.42 to 1.70.)

When they say that "effect sizes were … robust across priming methods and dependent variables", they mean that choice of testing language had roughly as big a priming effect as other sort of interventions did (for example, telling stories intended to promote collective vs. individual values).

And when they say that "effect sizes were … consistent in direction and size with cross-national effects", they mean that priming (whether by choice of language, or story-telling, or other methods) had about as big an effect as the differences among nationalities did, overall.

In this context, "priming" means that the researchers arrange for subjects to be influenced by some experimentally-manipulated factors that affect the thing being measured. Thus in a study measuring "individualism" vs. "collectivism", subjects might be primed by being seated at five-person tables vs. individual desks separated by partitions; or by being asked, before the test is administered, what they have in common with their family and friends, vs. what makes them different from their family and friends. Linguistic priming simply varies the language in which the questions designed to measure degree of invidualism vs. collectivism are asked and answered, or the language that subjects hear, read, or speak before a (perhaps-non-verbal) test is administered.

The idea, in Oyserman and Lee's words, is that

Priming activates mental representations that then serve as interpretive frames in the processing of subsequent information. When a concept is primed, other concepts associated with it in memory are also activated. When a cognitive style or mindset is primed, this activates a way of thinking or a specific mental procedure. Mindset priming involves the nonconscious carryover of a previously stored mental procedure to a subsequent task.

Note that language-choice priming, in this sense, is a way that language influences thought. But it's a non-Whorfian influence, in the sense that this influence need not be causally dependent in any way on any aspects of the form or meaning of the language. Nor are we talking about Wittgenstein's idea that "The limits of my language mean the limits of my world". Instead, these are psychological effects that might entirely be due to a language's cultural, social, and emotional associations for the individuals whose thoughts are being influenced.

[I should make it clear that none of the researchers I'm discussing are especially concerned with the effects of language choice on opinion-poll results. I've framed their work in those terms just because this seems to me to pose some of the issues in a clear way for outsiders.]

Now let's go back to David Laitin's 1972 experiments. He carried them out in schools in Waajeer, a Somali-speaking area of the Northeastern Province of Kenya. The experiments included an interview and a role-playing exercise, carried out among 64 subjects from the secondary school, with half of them doing the interview in English and the role-playing exercise in Somali, and half the other way around. In addition, a larger set of subjects participated in two easier-to-code exercises, where possible answers were more limited.

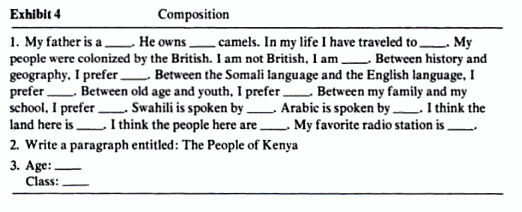

One was a listening test in which students were asked to evaluate the voice of English or Somali speakers, and the other was a "composition" test that involved choosing answers to fill in the blanks in sentences, either in English or in Somali. The composition test is the one under discussion here, and it was modeled on one originally developed by Leonard Doob for studying "patriotism and nationalism in the South Tyrol".

Laitin's English version of the test was this:

For the composition and listening tests, the subjects were the whole fifth year of the primary school (under 13 years old), and a set of volunteers from the first and second years of the secondary school (over 16 years old).

The two tables of results presented above come from Laitin's "composition test", and the language effects are very striking. Thus when tested in English, students preferred home to school 68% to 32%; when tested in Somali, they preferred dugsi ("school") to reer ("home") 75% to 25%.

The students were two different random samples from the same school, tested in the same setting by the same people within a short space of time.

It's easy to think of reasons for the difference, and Laitin suggests several. For example,

… in outlawing tribalism in the Somali Republic, the Supreme Revolutionary Council has proscribed the use of the word reer, which has rich clan overtones. Furthermore, the word I chose for school, dugsi, was once primarily used to denote Qur'anic schools, so is not an exact translation of "school".

He also suggests that in some cases, the students took the view that these were tests with right and wrong answers, and may have used out-of-classroom discussions to help their peers settle on the "right" answers. Some similar effects of group dynamics may even have taken place in the testing situation:

In both the composition and the listening exercises for the primary school students, although I tried vigorously to control it, the level of "shared" answers was probably high. With three students to a desk, and some forty-five students in a twelve-by-fifteen-foot classroom — a situation quite common in African primary education — most instructors recognize that the answers to their tests will reflect the collective consciousness of a particular desk. I may therefore have counted one independent observation (response form the desk) as three (response form three students). I could not collect a "desk" answer, because the relevant group was not always the desk, and because many students had answers that were different from those of other students at their desk or the neighboring desk.

Laitin also provides evidence that discussions of the tests were widespread even outside of the school:

After I completed all my testing, I spent a whole day quietly watching the local blacksmith making a knife out of a Land Rover spring and the horn of a cow. I had met him shortly after my arrival, and had told him I was working at the school. When a man walked in and asked the proprietor who I was, the proprietor answered that I was a student of languages, working in the local secondary school, giving tests to the students in both Somali and English, and planning to compare the answers to see if there were any differences. I was startled, not only because the metal workers were considered of low caste and therefore somewhat outside the society, but that anyone in the village would have such a clear idea of what I was doing. […] Insensitivity to the testing environment on the part of the experimenter, which this anecdote documents, is a serious problem.

But (at least in the context of this book) Laitin continues to believe in an effect that he thinks he saw as a Peace Corps volunteer in the Somali Republic in 1969:

I felt that there was a different social dynamic occurring among my students and colleagues when they were conversing in English and when they were conversing in Somali. I did not think that this difference was explained by their relative fluency in the languages, because I saw the same dynamic operating among Somalis who spoke English fluently, perhaps more fluently than Somali. And to a lesser extent (because my learning was much slower) I felt I myself was operating in a somewhat different world when I was speaking in Somali. Being a student of political theory, I began to relate the phenomenon I saw operating to ideas of cultural autonomy and political dependency. Could language be seen as a social institution which has its independent effects on other social institutions?

Except for the literature on linguistic priming of the individualism/collectivism dimension, I haven't been able to find any systematic discussions of language-associated mindsets and their effects on (for example) public opinion polling. It's well known that small differences in the way a question is phrased, even within a single language, can have big effects on polling results. What about differences in the accent in which a question is asked? And are there any well-supported methods of normalization that would make it possible to compare opinion-poll results across languages?

[Let me note in passing that Laitin's title Politics, Language and Thought is an instance of the X, Language, and Y pattern initiated (I think) by Franz Boas' Race, Language, and Culture. I have a feeling that there are a number of other examples, but this may be only because I once co-taught a course called "Biology, Language, and Culture". ]

peter mcburney said,

January 2, 2009 @ 11:17 am

Of possible relevance is work I published in Current Anthropology in 1988, on the failure in Zimbabwe of the Kish Grid, a standard western statistical technique used in sample surveys of individuals in households to ensure that realized samples systematically vary the interviewees across all types of household members, and do not only include those who speak first to the interviewer (eg, those answering the door or the phone). The technique failed in Zimbabwe because maShona households traditionally interface to the outside world via a designated spokesperson (often the youngest male child able to speak). Thus, asking another householder to speak to an interviewer is considered a breach of etiquette, something both potential respondents and interviewers had difficulty undertaking.

In any case, no matter who the designated spokesperson, a household's responses would usually be decided by the senior male present (possibly in consultation with other household members, possibly not), and so individual, as distinct from household, responses could not be obtained by household-centred surveys.

The presence of this effect led me to be very sceptical of the results of surveys of individual opinion gathered via household surveys, at least in Southern Africa, let alone attempt to compare surveys across cultures.

See:

P. J. McBurney [1988]: On transferring statistical techniques across cultures: the Kish Grid. Current Anthropology, 29 (2): 323-5.

Linda said,

January 2, 2009 @ 11:41 am

There is an interesting section about the effects of the interviewer on the results of a survey in "Infant care in an urban community", John and Elizabeth Newson, Allen & Unwin, 1963. This is the first part of their long term study on the actual practices of child care.

Most of the interviews were carried out by Health Visitors, people in uniform who are responsible for giving advice to mothers on how to look after their babies. The Newsons were concerned that this could effect the answers which the mothers gave to the questionnaire, so more interviews were carried out by researchers from the university to act as a control.

500 interviews were carried out by Health Visitors, 200 by university interviewers. Differences were detected between these two groups and pointed out in their book.

Elizabeth said,

January 2, 2009 @ 1:54 pm

Anecdote, rather than data, but when my work regularly required me to call people and ask them for information and/or assistance, I found it reliably true that women responded better to an English accent, while men were more likely to cooperate with an American Southern accent.

David Clausen said,

January 2, 2009 @ 4:35 pm

Davidson's: Truth, Language and History

Mark Liberman said,

January 2, 2009 @ 5:50 pm

Some other X, language, and Y books (with help from Cosma Shalizi):

Marc Shell, Money, Language, and Thought; Charles Morris, Signs, Language and Behavior.

Without the "and": Martin Heidegger, Poetry, Language, Thought.

And of course the famous permutation: Benjamin Lee Whorf, Language, Thought, and Reality, with its many echoes: Language, Thought, and the Brain; Language, Thought and Logic; Language, Thought, and Other Biological Categories; Language, Truth and Logic; Language, Thought, and Consciousness; Language, Thought, and Culture; Language, Thought, and Personality; etc.

Flooey said,

January 2, 2009 @ 8:41 pm

Also anecdotally, I feel like I've experienced this in Japanese class. When speaking to the teacher in English, I tend to treat her as an equal, and we'll have casual conversations on any kind of topic. When addressing her in Japanese, though, I speak deferentially, since that's the custom in Japanese culture. I think this is sufficiently ingrained that for the question "I consider my teacher to be my {equal, superior}" I would answer "equal" if asked in English and "superior" if asked in Japanese.

Liz Peña said,

January 2, 2009 @ 9:00 pm

We've found that bilingual children tended to give different word lists on a category fluency task in each of their two languages (Spanish & English). One of our examples is responses to asking these 4 to 7 year olds to name as many foods they could think of that they ate at a birthday party. Our top three reponses in English were: hotdog, hamburger, and cake; in Spanish (same kids): frijoles, arroz, y pastel (Peña, Bedore, & Giunta-Zlatic, 2002).

With respect to normalization of results across languages (and cultures), van der Veer, Ommundsen, Larsen, Van Le, Krumov, Pernice, & Romans (2004) discuss a procedure for calibrating or equating questionnaires on the basis of item salience. From what I remember, the procedure would be to normalize the questions within group and assign values (z-scores) to responders relative the norm.

Adrian Morgan said,

January 3, 2009 @ 12:43 am

Have there been any studies into what most people think "language influences thought" means as a hypothesis or statement? In my experience, non-linguists frequently accept it as being so, but don't differentiate between a Whorfian understanding of the connection versus the "cultural, social, and emotional associations" that you mention here.

Back at university, in an undergraduate course, I studied some of the material from the Cultura Project with particular emphasis on the sentence completion questionnaire. In one assignment I analysed my own answers to this questionnaire (I'm Australian), and in another I surveyed people from various parts of Europe. (I didn't get statistically meaningful results, but I was able to demonstrate some analytic skills.)

Some other students in the course chose to do an assignment into how language influences cultural values or something like that. In a class discussion of each others' research proposals I remember asking one such student if she'd considered whether some of the causality might run in the opposite direction. The fact that she hadn't was disappointing but not surprising given popular uncritical acceptance of the "language influences thought" meme.

Michael said,

January 3, 2009 @ 7:22 am

I wouldn't worry too much about Prof. Laitin's findings. His experiment would get an "F" in a 2nd year Research Mehods class in any psychology department…

[(myl) Perhaps, though I think that you should read his explanation of what he did and why he did it before assigning a grade.

But (this short section of) Prof. Laitin's book was just the stimulus for considering a more general issue. There appears to be quite a bit of evidence — for instance from the "linguistic priming" literature that I cited — that samples of bilingual subjects will often give a different distribution of answers, in a wide variety of testing situations, depending on the linguistic environment of the test. This can apparently sometimes be true even if the test itself indicates judgments or preferences non-verbally. And the differences in the answer distributions can be moderately large, comparable in size to the differences in samples (for example) from different national groups of mono-linguals.

This is not shocking or worrying or unexpected — we know that contextual associations of all kinds can have a substantial effect on many kinds of tests. But this general area seems understudied to me, given how much interest the whole "language determines thought" business generally evokes. That was the point of the post. ]

sjt said,

January 3, 2009 @ 11:08 am

_Culture, Language and Personality_, a collection of essays by Sapir.

chris said,

January 3, 2009 @ 7:10 pm

I work as a translator and occasionally I've had jobs passed on to me from agencies which require opinion poll questionnaires to be translated. Usually it's apparent from the text that the end customer is intending to conduct the "same" survey in different countries. I do the jobs but I should probably refuse, since I'm always struck by the pointlessness of it all. It's quite obvious that the questions I'm composing are simply not the same as the questions in the source language document. Such is the nature of translation. You simply can't ask the "same" question in several different languages. And if you try, the results from the various language groups are not going to be useful for anything more than a very rough and approximate comparison. This is why I'm always very sceptical of news reports of surveys puporting to show the relative "happiness" or whatever of people in different countries around the world.

It's especially bad when the question asks the interviewee "what comes to mind when you hear the word X" – in those cases I'll generally try to point out to the agency how totally useless the endeavor is. I suspect my objections fall on deaf ears, however.

Amy said,

January 4, 2009 @ 6:57 pm

I have a great idea: we can easily use language to judge the difference between individualism and collectivism by counting how many words for "me" there are in any given language!

Let's see… Me, Myself, I, Yours Truly, …

Jim Harries said,

January 5, 2009 @ 3:21 am

Interesting, that I also live and work in Kenya, as the Somali's researched above. In Kenya, as other Anglophone African countries, there is a 'dual' society. That is – the formal sector, and informal sector. That means that there are 'dual moralities', and everything else. These 'dual systems' are associated with different languages – English with the formal sector, and MT (mother tongues) with the informal sector. People are therefore used to giving answers according to 'sector', depending on language. If asked in English, give the answer that suits the formal / international sector. If asked in MT, give the answer that suits the informal / home / 'tribal' sector.

There is also Whorfianism in the above. As mentioned above, 'home' in English is not the same as in other languages, so school etc.

I certainly agree with Chris' comment on translation. Absolutely!

While not sure whether this blog is seeing anything entirely 'new'; I think this is an area in which there is need for vastly more awareness. Too many people, as Chris points out, naively ignore translation issues in their various international research projects – which become a mockery, to say the least.

For my articles, many on related themes, applied to Christian mission in Africa, see http://www.jim-mission.org.uk/articles/index.html

Grep Agni said,

January 5, 2009 @ 9:58 am

What about Twice as Less by Eleanor Wilson Orr? I read the book several years ago for an Education class.

The basic idea, from what I remember, is that BEV has differences from SAE that make certain mathematical ideas harder to learn unless the teacher is aware of the differences and adjusts to them.

For example, SAE distinguishes the constructions

(1) between X and Y

(2) from X to Y

Construction (2) indicates a direction whereas (1) does not. According to the author, speakers of BEV in (I think) Washington DC do not make this distinction, considering all distances directionless. Without the distinction already encoded in the language it is harder to distinguish the ray XY from the ray YX from the line segment XY.

The book is written by a secondary teacher for other secondary teachers and is not meant to be a rigorous linguistic study. People interested in linguistic determinism may find it valuable, however.

Karl Knechtel said,

January 28, 2009 @ 10:55 am

Adrian Morgan said,

"Have there been any studies into what most people think "language influences thought" means as a hypothesis or statement? In my experience, non-linguists frequently accept it as being so, but don't differentiate between a Whorfian understanding of the connection versus the "cultural, social, and emotional associations" that you mention here."

As a non-linguist myself (although I did take one vaguely related humanities elective and have a general interest in the subject), I'm drawing a blank on how the Whorfian understanding of the connection differs. In fact, I'm drawing a blank on what other understanding of the connection could possibly exist! To me "language influences thought" means simply that the language you're speaking has an effect on (influences) what thoughts you have, and that's all there is to it, and that's what we see at work in Laitin's results. As for *why* such an influence would occur, "cultural, social and emotional associations" would seem to cover an awful lot of ground, no?