A fair-use victory for Google in these United States

« previous post | next post »

US Circuit Judge Denny Chin has ruled in favor of Google in its long-running copyright litigation with the Authors Guild over the scanning and digitization of books. Chin ruled that the Google Books project constitutes fair use because it is "highly transformative" and "provides significant public benefits." In explaining those public benefits, Chin cited the use of Google Books data for Ngram queries, and pointed to a research example that we've discussed several times on Language Log.

In his opinion (embedded here, PDF here), Chin writes:

The benefits of the Library Project are many. First, Google Books provides a new and efficient way for readers and researchers to find books. […] Second, in addition to being an important reference tool, Google Books greatly promotes a type of research referred to as "data mining" or "text mining." (Br. of Digital Humanities and Law Scholars as Amici Curiae at 1 (Doc. No. 1052)). Google Books permits humanities scholars to analyze massive amounts of data — the literary record created by a collection of tens of millions of books. Researchers can examine word frequencies, syntactic patterns, and thematic markers to consider how literary style has changed over time. (Id. at 8-9; Clancy Decl. ¶ 15). Using Google Books, for example, researchers can track the frequency of references to the United States as a single entity ("the United States is") versus references to the United States in the plural ("the United States are") and how that usage has changed over time. (Id. at 7). The ability to determine how often different words or phrases appear in books at different times "can provide insights about fields as diverse as lexicography, the evolution of grammar, collective memory, the adoption of technology, the pursuit of fame, censorship, and historical epidemiology." Jean-Baptiste Michel et al., Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books, 331 Science 176, 176 (2011) (Clancy Decl. Ex. H).

The cited amicus brief, written by Matthew Jockers, Matthew Sag, and Jason Schultz (PDF here), provided Chin with the "United States is/are" example:

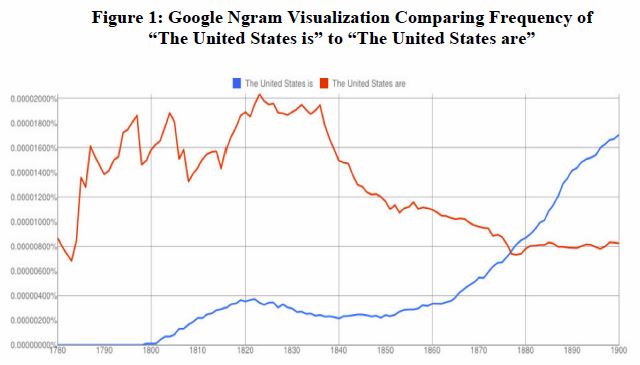

Google’s “Ngram” tool provides another example of a nonexpressive use enabled by mass digitization—this time easily visualized. Figure 1, below, is an Ngram-generated chart that compares the frequency with which authors of texts in the Google Book Search database refer to the United States as a single entity (“is”) as opposed to a collection of individual states (“are”). As the chart illustrates, it was only in the latter half of the Nineteenth Century that the conception of the United States as a single, indivisible entity was reflected in the way a majority of writers referred to the nation. This is a trend with obvious political and historical significance, of interest to a wide range of scholars and even to the public at large. But this type of comparison is meaningful only to the extent that it uses as raw data a digitized archive of significant size and scope.

It's heartening to see the "United States is/are" example serve such a central role in the decision. I first discussed how "the United States are" gave way to "the United States is" in a Language Log post back in 2005, "Life in these, uh, this United States," and followed it up in a Word Routes column in 2009, "The United States Is… Or Are?." Later that year, Mark Liberman posted on the topic here, here, here, and here.

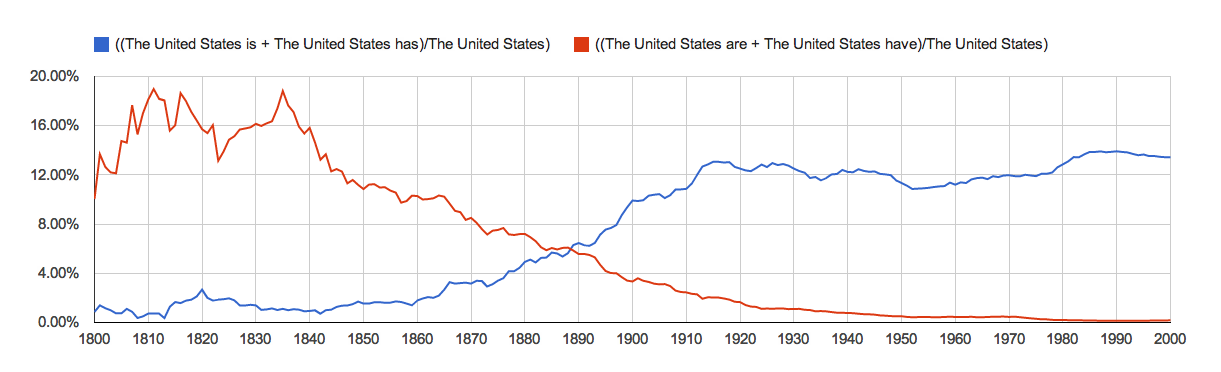

But that was all before Google rolled out its Ngram Viewer in December 2010, which allowed for the ready visualization of the trend, as given in the amicus brief. And when a new version of the Ngram Viewer was released in October 2012, I turned to the example yet again in an article for The Atlantic, as a way to show off some of the new features. Here is the query I included:

(If you missed it, just last month the Ngram Viewer was again freshened up with even more new features, including wildcard searching. See my Atlantic piece and the announcement on the Google Research blog.)

Finally, I was happy to receive an advance copy of the book Uncharted: Big Data as a Lens on Human Culture by Erez Aiden and Jean-Baptiste Michel, the brilliant young researchers who worked with Google to develop the Ngram Viewer and introduced it to the world in their paper for Science, "Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books." In their book (coming out next month), Aiden and Michel walk the reader through a series of enlightening examples of how the Ngram data can be used to analyze trends in language and culture (what they dubbed "culturomics" in the Science paper). The very first example in the book? You guessed it: the shift from plural to singular "United States." Now, that's an example with legs.

Erez Aiden said,

November 14, 2013 @ 12:28 pm

Credit where credit is due: Mark Liberman first asked us whether we could probe the is/are transition for the United States. Answering his question became one of the fixed points that helped us think about the whole project.

(Of course, the excerpt in the book is indebted to your pieces, as well, Ben!)

Also relevant is the amicus brief JB and I wrote to judge Chin, on this topic, back in 2009, see:

https://sites.google.com/a/pressatgoogle.com/googlebookssettlement/letters-of-support

http://bit.ly/I13qNA

This was before we had the US is/are ngram – apparently 'influenza', 'cholera', and no chart was insufficiently convincing!

dw said,

November 14, 2013 @ 1:46 pm

This could be huge. What, if anything, does it mean for "orphaned" copyright works?

Barbara Partee said,

November 14, 2013 @ 5:18 pm

Congratulations, Mark, Ben, Erez, and Jean-Baptiste! That's a brilliant choice of example to study, a brilliant tool that we now have to study it with, and a really cool use of a linguistic argument in an important case!

Rubrick said,

November 14, 2013 @ 5:50 pm

This would have been a more apt comment on one of the previous posts, but — I'm astonished that these lines don't cross until the late 1970s. Did I really hear things like "The United States are still recovering from Viet Nam and Watergate" when I was a kid? It sounds completely odd to me now. (I believe it, I just can't believe it.)

Jan Schreuder said,

November 14, 2013 @ 7:33 pm

@Rubrick. Look again. Your memory served you well. The lines cross in 1890.

Lazar said,

November 14, 2013 @ 8:09 pm

@Rubrick: That's the 1870s, not the 1970s.

David Morris said,

November 15, 2013 @ 4:44 am

In an idle moment today I wondered about the comparative use of 'cannot' and 'can't'. I typed them into Ngrams and was told that it processes both as 'can not', and showed me one line (which, by the way, declines over time).

[(myl) I agree that the can't/can not conflation is unfortunate. Some non-Ngrammatic investigation of contraction history can be found in "True Grit isn't true", 12/29/2010, and "Norwood", 12/30/2010.

And here are the percentages of can't-contraction according to COHA, from 1820 to 2000:

5 14 14 22 29 32 34 37 45 54 55 59 59 63 62 65 67 77 80

]

David J. Littleboy said,

November 15, 2013 @ 6:10 am

Wow! You mean Science actually published a decent paper in the social sciences? From reading Language Log one would think that never happened.

Jay Lake said,

November 15, 2013 @ 6:18 am

Speaking as an author (10 novels, 6 collections, about 400 short stories, so with a boatload of copyrights to my name), this is an absolute disaster. The Google Books Settlement, which is what was behind this lawsuit, creates a class of copyright license never before seen in Anglo-American copyright law. Essentially, Google can proactively assert a license without my permission, based on criteria established and policed by them for which I have no legal appeal, and set the value of the copyright likewise. This takes out of my hands the licensing terms, for the first time in history.

Imagine if you owned a cabin by the lake. Google could come along, occupy it on their own initiative, and declare the rent to be $5 per month. That's a fairly precise analogy of the GBS.

Mind you, I think the Google Books project is awesome. It's the Google Books Settlement that is absolutely poisonous to content creators. An attempt to deal with the problem of orphan works, it has vastly overreached. If all this stands, imagine the abuses that will propagate once Hollywood begins asserting proactive copyright rather than being required to negotiate options from content creators. Just one simple example of the problem.

[(myl) I haven't read the decision, but as I understand the press reports, the decision would not apply to an application that is clearly beyond the bounds of Fair Use, e.g. by charging for access to the content, or by depriving the content owner of normally-expected revenue. So in particular, it seems that Hollywood is not in a better position now than it was before. Is that wrong?]

quixote said,

November 15, 2013 @ 11:49 am

I'm way out in the leftward ozone on copyright: I think everything should be freely available and, using tracking software, royalties would accrue to the creators (nontransferable), paid for out of a tax on the physical media and hardware needed to use it. (Yes, I realize I'm advocating compulsory licensing. I'm an author so minor as to be microscopic, so I guess I can say I don't really have a dog in this race.)

So, with that wild-eyed radical position as background, I should be happy with the Google decision as a step in the right direction. But I find it just makes me nervous. Google isn't doing this to advance access to the world's knowledge. It's doing it for profit. And if their past behavior is any indication, it has no intention of sharing that profit with the people who generate it. (When was the last time you received a check from them for all the money they make tracking you?)

That just feels wrong. I can't quite articulate why when a multibillion dollar company is doing it for profit it doesn't feel like fair use. But it doesn't. Like Jay Lake, though maybe for different reasons, I have the feeling no good will come of this.

J. W. Brewer said,

November 15, 2013 @ 12:11 pm

Jay Lake's concerns are separately misplaced because there is no "Google Books Settlement." The proposed settlement (with its novel licensing features) blew up and did not get the necessary judicial approval (see history in http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Books_Settlement), which is why it was necessary for the parties (all of whom had supported the settlement) to litigate the merits and get this decision. If you are sufficiently cynical about what was really going on with the proposed settlement (I know some people were, although I didn't follow the issues closely enough to have an informed opinion one way or another) it is possible that Google is now worse off having (subject to appeal) technically won an absolute victory than it would be if the settlement had been approved.

Pace quixote, one positive outcome might be that various other outfits out there (including perhaps non-profits?) might have been interested in doing similar things but have thus far been deterred from doing so by the risk of copyright infringement liability. Google, as an entity with the resources to spend bajillions on legal fees and still have it be rounding error to its overall financial situation, was thus able to take the lead in clarifying (assuming this decision sticks and is followed by other courts . . .) the law when others might not have been able to afford the cost of doing so, so that less deep-pocketed organizations can (again, subject to appeal and other waiting-for-the-dust-to-settle) feel free going forward to act in the now-clarified-as-not-infringing area of activities without needing the resources to pay their own lawyers to defend a lawsuit of this magnitude.

Coby Lubliner said,

November 15, 2013 @ 2:33 pm

While Google Ngram Viewer shows the interesting result that "the United States is" passed "the United States are" around 1870, it also shows that "these United States" still overwhelms "this United States" (and the latter may include constructions like "this United States citizen"). Clearly, in English the singular/plural dichotomy is not as rigid as some believe (see also singular they).

Lazar said,

November 15, 2013 @ 3:22 pm

@Cory Lubliner: Yeah, "these United States" seems quite natural to me, in a poetic sort of way, whereas "this United States" isn't something I'd ever say. English also has the issue of collective nouns being treated as plural, which is associated with British usage, but not totally absent from the US either. And then there are those sorts of conjoined subjects, like "research and development" or "popping and locking", which often take singular verbs.

Andy Averill said,

November 15, 2013 @ 3:24 pm

Hate to be Mr Yesbut, but — please note this is only a ruling from the circuit court, and the Authors Guild has already said they'll appeal. So we haven't heard the last of this case.

Chris Waters said,

November 15, 2013 @ 3:25 pm

J.W. Brewer: re non-profits. At least at one point, the Internet Archive and the New York Library Association were opposing the previously proposed settlement, because the Book Rights Registry it created "would create a de facto exclusive license for Google because the deal grants no rights to the BRR to license books to competitors – copyright owners will have to license Google’s competitors voluntarily, while Google gets an involuntary, virtual compulsory license through class action process." (Quoting Wikipedia.)

I'd really like to find out more about what happened with that side of the issue, because I'm an even bigger fan of the Internet Archive than of Google.

Willy said,

November 15, 2013 @ 4:45 pm

Andy: Note that while this was a decision by a (now) appellate judge, it is a district court decision, so the appeal will be to the circuit court in the first instance.

J. W. Brewer said,

November 15, 2013 @ 5:51 pm

I don't think "this United States" (as a freestanding NP, not as a truncated part of e.g. "this United States citizen") is even grammatical in my idiolect. That coexists without any consciously felt dissonance with the same idiolect treating "the United States" as singular rather than plural for purposes of verb agreement.

maidhc said,

November 16, 2013 @ 12:05 am

It's definitely not the first time copyright owners have not been able to negotiate licensing terms. Anyone can record a copyrighted song without negotiating or seeking permission from the copyright owner, upon payment of the statutory mechanical royalty rate for physical recordings, which is currently 9.1¢ per copy for recordings of a song 5 minutes or less.

Ethan said,

November 16, 2013 @ 3:20 pm

The court opinion is short, cogent, and well worth reading. I think any discussion of "forced copyright licensing" totally misses the point. The core ruling is that Google's actions are fair use, and thus justifiable regardless of who holds or licenses the copyright. Furthermore, the fair use in question is carefully distinguished from creating or making available a copy of the original work in a form that would compete with the normal exercise of copyright by the copyright holder. Jay Lake's analogy of forced rental of a vacation home is flawed; a better analogy would be collecting and publishing statistics on the number, attributes, and distribution of vacation rentals without contacting the individual owners to ask if they wanted their property to be part of the tabulation. I hasten to add that is my analogy, not the court's. The ruling also specifically addresses, and dismisses, concern that Google's ultimate interest is monetary.

It seems to me that the constituency with a legitimate reason to feel harmed by this ruling is not authors, but potential competitors for Google's niche as a "place to go" for data mining. I imagine that a project equivalent to Google Books could have been launched as an internet enterprise with a business model of selling access, i.e. another Nexus/Lexus or Thomson ISI. But this opportunity has been preempted by Google. As a researcher, I think this is a good thing. If I were an entrepreneur I might think otherwise.

Rubrick said,

November 16, 2013 @ 3:49 pm

Geez. That's what I get for failing to embiggen.

Chris Waters said,

November 16, 2013 @ 6:50 pm

@Ethan:

The Internet Archive's model is absolutely not "selling access". In fact, unlike Google, they're a non-profit, registered member of the American Library Association, and supported mainly by funding from the Smithsonian. They also have one of the largest on-line collections of public domain and creative-commons films and music. And they neither charge for access nor support themselves with ads.

The moment the IA joined the suit against Google is the moment I began to have doubts about Google's position in all this. Which is why I really want to find out more about where they stand today. (I know they're continuing to scan books on their own, but I'm not sure if it's limited to public domain works.)

Polyspaston said,

November 16, 2013 @ 10:28 pm

The whole ruling is infuriatingly imperialistic, in that it gives Google rights globally on the basis of US law. Not everywhere has 'fair use' – notably the UK does not – but Google can still, effectively, use the work of British authors under this ruling and make it available in the UK.

It is, to say the least, an enormous presumption to rule in this way, and effectively a claim by America to owning the internet, everything on the internet, and, indeed, via Google scanning, presumably all written material.

Ethan said,

November 17, 2013 @ 12:41 am

@Chris Waters: I cannot find a position paper from the Internet Archive that specifically relates to the current AG v. Google case. Their earlier opposition was to the proposed "Google Books settlement" that the court later voided – leading to the current case. So I don't know where the Internet Archive stands on the issue today, but as I understand it their original objection was along the same lines that I outlined above – that Google was effectively preempting the niche of building an archive of scanned material. That is quite a different thing from believing that this is something that should not be done by anyone at all.

The Hathi Trust is another big player in this game, doing pretty much that same thing that Google is but (1) they are a non-profit and (2) they do not have Google's universally known public face. The Authors Guild brought and lost a similar case against HathiTrust that is currently on appeal.

Mark Dowson said,

November 17, 2013 @ 4:38 pm

@polyspaston: UK law (1988 copyright act) recognizes "Fair Dealing" which is similar to (not exactly the same as) US Fair Use (Fair Dealing has a quite different meaning in the US related to financial disclosure by companies).

Both US Fair Use and UK Fair Dealing (and equivalents in many other countries) allow copying for research purposes, so if Google copied just to be able to derive Ngram frequencies or similar measures, they wouldn't violate copyright – or be particularly imperialistic.

Chris Waters said,

November 17, 2013 @ 5:47 pm

@Polypaston: The suit was filed in the US, so it's hardly "imperialistic" for the US courts to rule on the matter before them. And yes, "fair use" applies in the US to non-US works, and always has. Someone accused of copyright infringement in the US will be judged by US law, no matter where the creator might live. International copyrights are governed by treaty.

Of course, Google can still be sued in another country…

J. W. Brewer said,

November 18, 2013 @ 11:13 am

The internet can help avoid the burdens imposed by overly onerous copyright regimes in multiple directions. Many English-language works that are still under copyright in both the U.S. and U.K. have now entered the public domain in Australia (perhaps Big Copyright did not invest enough in campaign contributions to legislators there?), and are thus made freely available via the Australian version of Project Gutenberg, which rumor has it can sometimes be accessed by readers not themselves physically located in Australia.

dw said,

November 18, 2013 @ 10:47 pm

@Jay Lake:

If you don't want Google Books to index your content, you can tell it not to.

dw said,

November 18, 2013 @ 10:49 pm

@Polyspaston:

The ruling only applies in the US. And, if you're feeling imperialized, I'm sure English libel and privacy lawyers will figure out a way to fight back :)

Hank Bromley said,

November 20, 2013 @ 2:38 am

Several commenters have mentioned the Internet Archive and asked how the Archive views the Google decision.

The Archive did oppose the "Google Books Settlement," and welcomes Judge Chin's ruling that Google's activities qualify as Fair Use.

Archive founder Brewster Kahle has posted a reaction on the Archive's blog:

http://blog.archive.org/2013/11/16/let-the-robots-read-a-victory-for-fair-use/

(I am an Archive employee, but do not speak on behalf of the organization.)