Word (in)constancy

« previous post | next post »

For a peek at what makes language — and Language Log — possible, consider this. Suppose that you stand up in front of a class of kindergarten or first-grade kids, who haven't learned to read and write yet, and tell them "Today we're going to play a game. I'll tell you a story — and any time I say 'school', the first kid that raises a hand gets a dollar."

If you tell a good story, and manage the interaction right, there'll be many occasions of group glee. (A Jon-Stewart-style hammed-up doubletake, when they miss a keyword instance, should be quite effective.)

But in general, as long as you speak clearly, most of the arguments are going to be about whose hand went up first, not about whether what you said was actually school or something else.

Now, for a peek at what makes the study of intonation difficult, imagine trying the game a different way. Instead of offering a bounty for instances of a word, ask them to raise their hands for instances of a pitch contour.

The first problem is how to describe the task. You could try "… any time I ask a question with my voice, like this: 'are you having a good time?'" But that sort of instruction is likely to result in confusion if you ask a question without a final rising contour, or if you use final rises for some possibly different function ("… at snack time, you can have a fig newton/ or an oreo\.") You could try "… any time the pitch of my voice goes up …" but this will probably be worse, since any high pitch might trigger some responses.

Whatever description that you use, the most likely result will be a lot of blank stares. And if you can get the kids to participate actively, the arguments will mostly not be about who raised their hand first, but about whether anyone's hand should have been raised at all. Occasions of group glee are likely to be few.

Grown-ups, including experts, are not in a much better situation. For an illustration, let's start with the start of a story from one of the Limmy's World of Glasgow podcasts, which came up in an earlier post:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

The psychological phenomenon of word constancy continues to apply, even for someone like me who is unfamiliar with Xander's Glaswegian accent and Glaswegian cultural context. I can recognize his words — though it might take a couple of hearings in some cases — and identify (most of) them with words that I know. At the same time I can recognize that they're pronounced in a different way, and because I know something about phonetics, I can be much more exact about the differences. I can also recognize that he often uses shared words in a somewhat different way as well.

For example, there's the word headmaster. I'd pronounce it something like [ˈhɛdˌmæs.tɚ]; Xander says something like [ˌhidˈmes.θɚ]; but we still easily recognize that it's the same word. We can discuss the difference in stress patterns, or the way that Xander's vowel system is shifted relative to mine. If we want, we can measure formant frequencies in order to compare the vowel qualities quantitatively.

And we can refer to a good dictionary for more about the history of this word and its parts. Thus head is an inherited Germanic word, originally referring to "the upper division of the body, joined to the trunk by the neck", and here used figuratively for "a person to whom others are subordinate"; while master is from Latin magister, originally "a person or thing having control or authority", and here meaning "teacher".

In most parts of the U.S., the "head teacher" of a public elementary school would be called the "principal" rather than the "headmaster".

Now consider the intonation contours in Xander's story. Let's zero in on a shorter segment:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

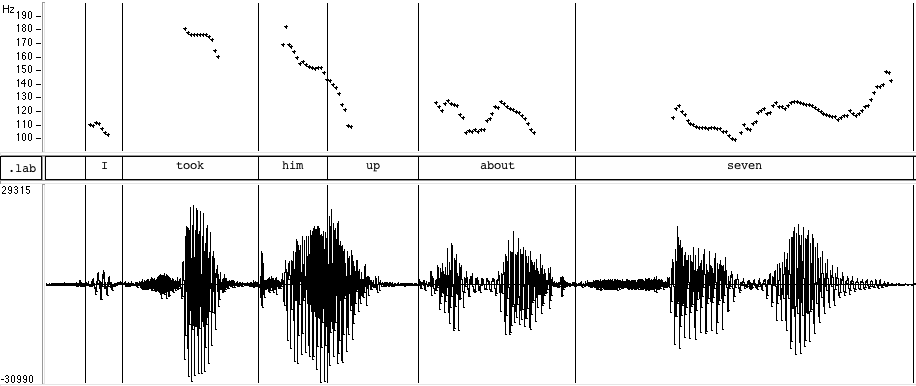

I took him up about seven

it was the same school as I went to

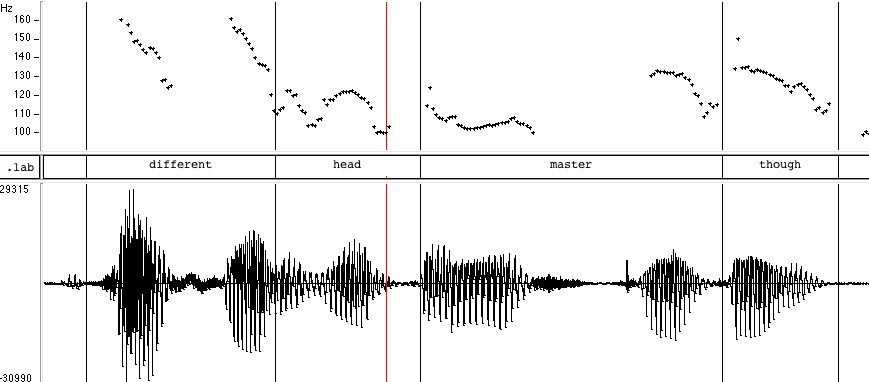

different head master though

Are the intonations at the end of the three phrases all the same? Partly the same and partly different? I think they're essentially the same pattern, but some people might disagree with me.

Let's listen carefully while examining the pitch contours.

Comparing the first two phrases, there's a brief final rise during the low-amplitude [n] murmer in "seven", whereas "went to" drifts downward to the end. The accented ("nuclear") syllable in "seven" is level in pitch, with the rise happening during the consonant between the word's two syllables, while the nuclear syllable "I" is rising, with the following syllable "went" continuing the level reached at the end of "I". And in the second phrase, there's a sort of shared prosodic focus between "same" and "I" that doesn't seem to have any counterpart in the first phrase.

(Click on the images for larger versions.)

And what about the nucleus and tail of the next phrase, "(head)master though"?

My own opinion is that all three of these phrases end in the essentially the same pattern, with the differences due to segmental effects, random variation, and modulation to express higher-level structure.

Now listen to this passage spoken by a 47-year-old woman from New York:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

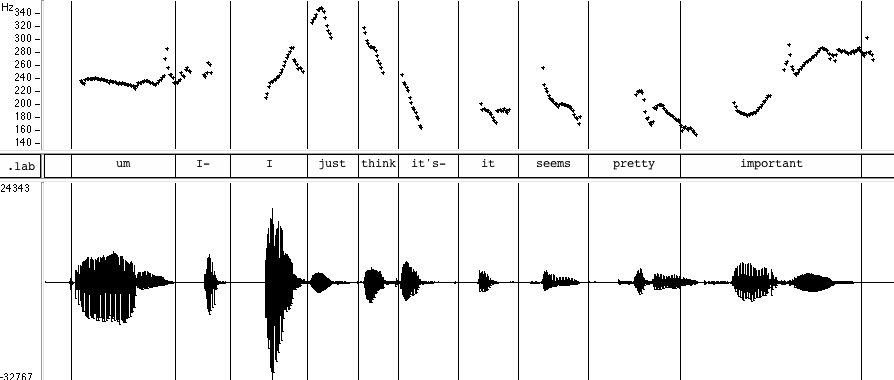

um I just think it's- it seems pretty important

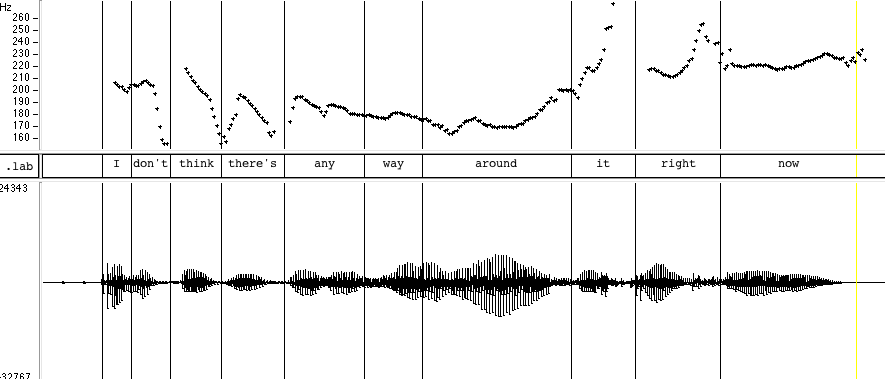

um I don't think there's any way around it right now

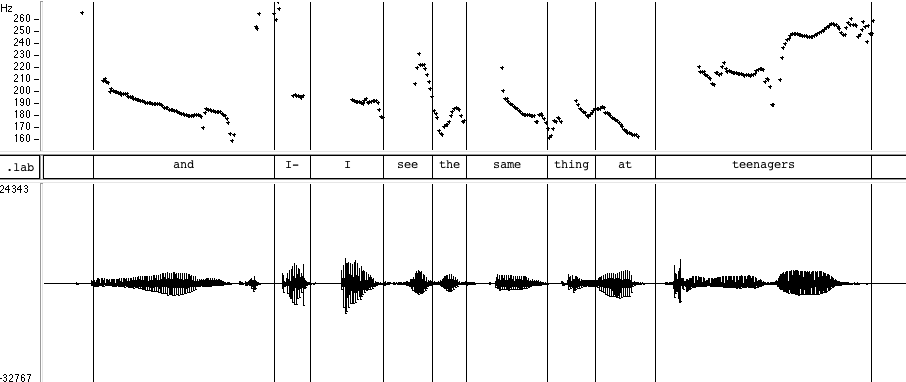

and I- I see the same thing as teenagers

and- I mean they use the computers for everything and I-

students in first second third grade that I'm doing- I'm student teaching with right now

and they

even use the computers for um

just all kinds of stuff at school that-

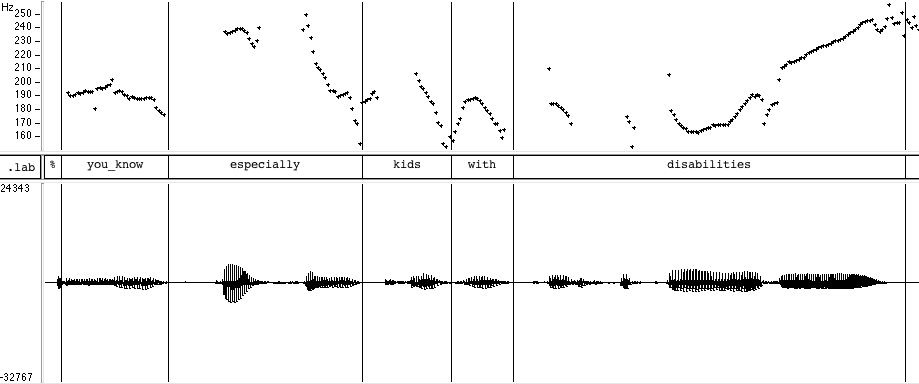

you know especially with kids with disabilities

it's just a huge help to them

There's a similar series of rises associated in various ways with the nuclear accents of her phrases. Again, there are differences in whether the rise occurs before, during, or after the nuclear syllable; whether the "tail" levels out or continues to rise; and so on.

Are the following four samples all instances of the same prosodic pattern? Are any or all of them instances of the same pattern(s) as Xander's melodies?

This one has the lowest point preceding the accented syllable; the rise is shared between the accented syllable and the first part of the following syllable; the tail is level:

This is similar, except that the start of the accented syllable is just about as low as anything that precedes:

In this one, however, the accented syllable starts more than half way up between the low point and the end:

And here the rise continues throughout the "tail":

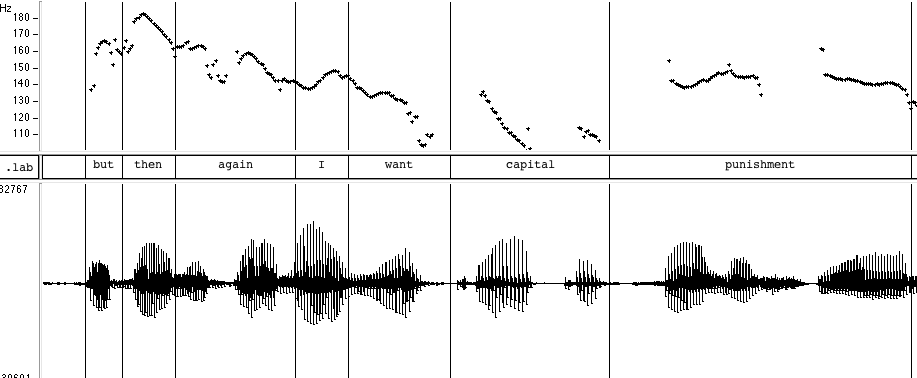

Here's another example. The speaker is a 34-year-old woman from Virginia:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

see that- that'd be the way to go I think

but then again I want capital punishment

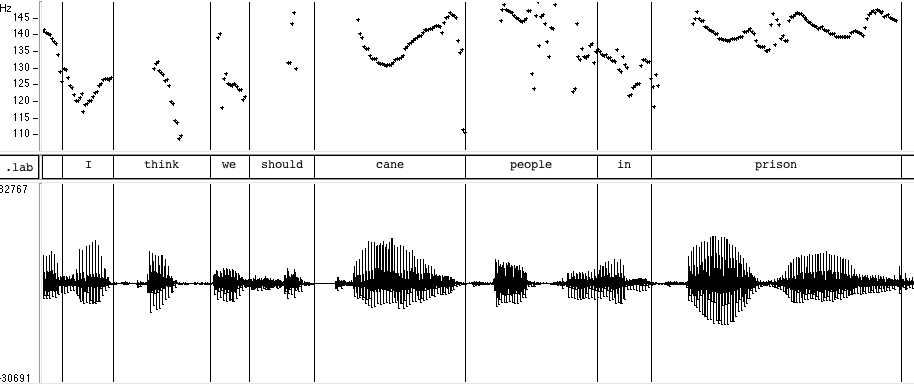

I think we should cane people in prison {laughs}

In the second phrase in this passage, the final accented word "punishment" is nearly high-mid level, with only a slight rise on the accented syllable, and the lowest point is on the previous word "capital":

In the next phrase (or pair of phrases), "cane people" rises from a mid pitch and then levels off; "in prison" seems to be a separate phrase with another high level ending pattern:

So what do you think? Whether by listening and reacting naturally, or by looking at pitch contours and cataloguing their features, are you confident that you know whether these nine examples are all the same prosodic pattern, or are instances of nine different prosodic patterns, or should be assigned in some way to three or four or five or six categories? Or are you convinced that such questions are badly posed?

Whatever you think, you can probably find some researchers who have roughly the same opinion that you do.

Such questions have been discussed and debated for more than half a century, and the number of extant opinions is still increasing rather than decreasing. These nine examples were all cases of more-or-less rising phrase-final contours on statement-like utterances. The situation becomes even more divergent as we bring in the use of rises in yes-no questions, or in explicit lists, or in the protasis of conditionals, or in the explicit presentation of alternatives. The main reason for this divergence, in my opinion, is that there's no intonational equivalent to the phenomenon of word constancy, which is what makes most linguistic analysis (including most phonetic analysis) possible.

Some other morning, I'll take up some ideas about what sort of research program might help prosodic theories to converge rather than diverge.

But for now, let's be grateful that we can rely on word constancy in most areas of linguistics. Sound is infinitely variable, and meaning is deeply mysterious. But words are the rock on which we build systems of analysis and description that make sense of sound patterns.

Bryn LaFollette said,

September 16, 2008 @ 2:32 pm

Something I've always been rather amazed at is how our mental parsing aparatus is able to make such seemingly definite distinctions about the consistency of words. To be sure, when comparing pitch contours one is hard pressed to come up with clear catagorical seperations. But, when one starts trying to pick out specific occurances of a given word in a spectrogram of a whole sentence by identifying the formant structure of its vowels or identifying its stop constonants based on the velar pinch of adjacent formants or analogous clues I, for one, am awed by how easily my mind seems to make those distinctions seem so clear when my eyes clearly don't.

A while back I was doing phonetic research on phonemic tone distinctions and I was collecting recordings in Mandarin from a number of native speakers to illustrate the full range of tone contours that make up the phonemic inventory of that language. In my recordings, I was collecting instances of a series of terms with each word spoken in isolation as well as within the context of a sentence. When I finally got to examining the recordings on the computer, I was amazed at how while I could easily see the characteristic pitch contours of the phonemic tone on the isolated words, picking it out in the context of a sentence's pitch contour was just beyond me in most every case. In same cases the pitch contour that corresponded to the word seemed to have moved off of the word itself or, at the sampling rate I was using, seemed so short as to obscure any contour at all. And yet, any Mandarin speaker will still clearly be able to correctly identify the word within that context, including the crucial tone information, and with the control of Mandarin I had that time, I felt confident in recognizing these words as well from the recordings even though I didn't see a way I could link the right tone with the right word based on the pitch contour graph.

I wonder how it is that given these other areas in which we seem to have such definite intuitions about discrete units, no one seems to have such definite intuitions for intonation patterns.

Sandy Ritchie said,

September 16, 2008 @ 8:51 pm

Intuitively, just from listening to the clips, I'd say that each is a different use of the more-or-less rising phrase-final contour. The guy from Glasgow uses it because that's how Glaswegians usually intone declarative sentences (from my limited experience: I lived four years in Edinburgh); the woman from New York seems to be using it to indicate that she is thinking on her feet and the listener shouldn't take this as her definitive thought on the matter; the woman from Virginia is using to indicate that the opinions she states are a list – punishment has the nearly high-mid tone and cane people (in) prison the higher one.

I can see the problem in grouping them prosodically though. Some people might say they're all instances of 'uptalk'. Is uptalk a useful category?