The culturomic psychology of urbanization

« previous post | next post »

Patricia Greenfield, "The Changing Psychology of Culture From 1800 Through 2000", Psychological Science 2013 (pdf):

The Google Books Ngram Viewer allows researchers to quantify culture across centuries by searching millions of books. This tool was used to test theory-based predictions about implications of an urbanizing population for the psychology of culture. Adaptation to rural environments prioritizes social obligation and duty, giving to other people, social belonging, religion in everyday life, authority relations, and physical activity. Adaptation to urban environments requires more individualistic and materialistic values; such adaptation prioritizes choice, personal possessions, and child-centered socialization in order to foster the development of psychological mindedness and the unique self. The Google Ngram Viewer generated relative frequencies of words indexing these values from the years 1800 to 2000 in American English books. As urban populations increased and rural populations declined, word frequencies moved in the predicted directions. Books published in the United Kingdom replicated this pattern. The analysis established long-term relationships between ecological change and cultural change, as predicted by the theory of social change and human development (Greenfield, 2009).

This may remind you of Jean Twenge's work on alleged recent increases in narcissism (see "What does this graph mean?", 7/15/2012), but Prof. Greenfield's paper looks at a broader historical scope (1800-2000 rather than 1960 to 2008), and also explores the predictions of a theory about the effects of urbanization, rather than just a conviction that Kids Today are too self-involved:

The Google Books Ngram Viewer is a new tool for the quantitative analysis of long-term culture change. The hypotheses were generated from my theory of social change and human development (Greenfield, 2009). A central theoretical claim is that different value systems, behaviors, and human psychologies are adapted to different types of ecology. The ecological level of the theory is based on the ideal types of gemeinschaft (community) and gesellschaft (society) developed by the German sociologist Tönnies in the 1800s (1887/1957). A key characteristic of gemeinschaft environments is that they are rural; other interrelated characteristics are subsistence economies, simple technology, and low levels of wealth (cf. Inglehart & Baker, 2000). Education takes place at home around practical skills. A key characteristic of gesellschaft environments is that they are urban; other interrelated characteristics are commercial economies, complex technology, and high levels of wealth. Education centers on school and the development of the mind. These characteristics of the ideal types anchor quantitative dimensions in the theory of social change and human development.

On the other hand, Prof. Twenge's foray into Culturomics was based on a statistical analysis of the frequency over time of 20 "communal" words versus 20 "individualistic" words, where the communal/indiviudalistic value of the words were based on an extensive rating experiment. In contrast, the word-related evidence in Greenfield's article is limited to graphs of three specific word-pairs ("obliged" vs. "choose", "give" vs. "get" and "act" vs. "feel", along with one slightly larger comparison ("obedience, authority, belong, pray" vs. "individual, self, unique, child").

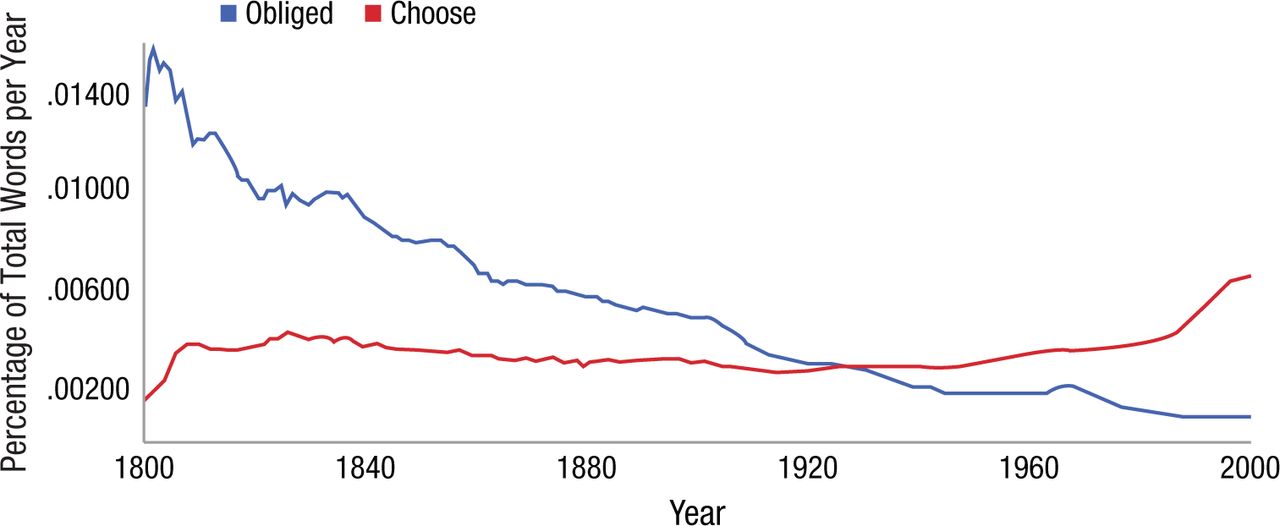

Greenfield's first piece of evidence is a graph showing the frequency of "obliged" vs. "choose" as "indexing the values" of "social obligation" vs. "individual choice", as produced by the Google Books ngram viewer with a three-year smoothing window:

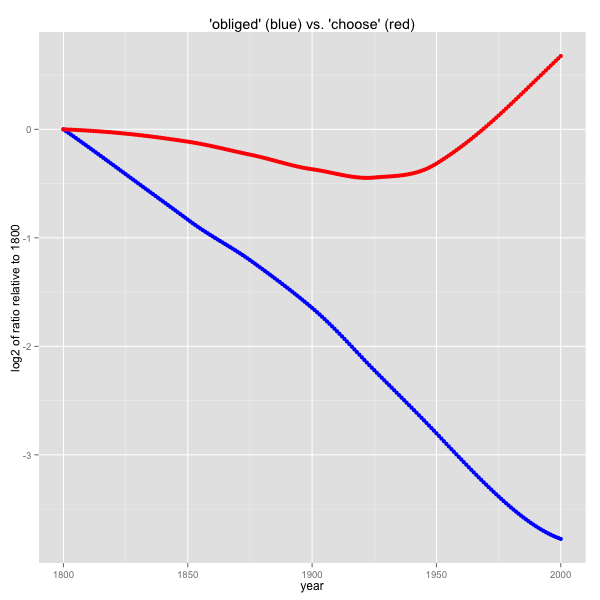

Another way to plot the same sort of thing, which doesn't require finding word-pairs that happen to be similar in overall frequency, and arguably does a better job of showing the overall trend, is to show the loess fit to the same data points, scaled so as to show percentage changes since the start of the time-period under investigation. Here's my version:

[Wonkish aside: In order to plot increasing and decreasing trends in a symmetrical way, I've used R's loess() function to get the local trend lines, and plotted log2() of the ratio of all (fitted) points to the initial value of the fitted data, so that a value of 1 translates to doubling of the (fitted) frequency, while a value of -1 translates to halving the frequency.. If you want to look at it a different way, here's the raw (unsmoothed) ngram data for obliged and for choose — and some R code that will generate the above graph is here.]

But there's room to doubt how well these particular words are actually "anchored" by the "ideal types" that Greenfield is interested in. Is the word "obliged" really a good index for gemeinschaft-type "social obligation and duty"? In a random samples from 1840 and 1850 in COHA, I find that about a quarter of the uses of "obliged" refer to obligation by physical circumstances rather than obligation by social norms or social connections, e.g.

… the gale increased to such a degree that the boats were in imminent danger of foundering. The officers were obliged to order their supplies of water to be thrown overboard, in order to lighten the burden.

… the severity of the weather obliged him to return before he had reached Icy Cape.

… so weak he was obliged to be carried on board in a litter …

… they proved so dirty she was obliged to throw them away.

… now the hot weather was coming, it seemed almost insupportable, as we were obliged to have a fire in the close room, in order to cook our provisions …

The cars were just on the point of leaving, and they were obliged to run in order to catch their chance.

… often checked by precipices, and obliged to seek fords at the heads of tributary streams …

And another substantial percentage involves the obligations of urban "commercial economies", "personal possessions", or "child-centered education", rather than "social belonging" or rural "authority relations":

the ruin of those who were obliged to receive the notes at their nominal value was insured

It might, however, be more agreeable to pay a vo!untary tax for luxuries which they were not obliged to use, than to pay a forced and inevitable one on real estate

those who were obliged to accept payment on a previous bargain in a word, all creditors were ruined, because they were obliged to accept a value purely nominal.

Were the manufacturer obliged to leave his labor, to sell a yard of calico, the price of calico would be trebled.

exchanged their receipts for bank notes, which obliged the bank to raise the issue as high as a billion

Similarly, the word "choose" is not always a reliable index of "the development of psychological mindedness and the unique self":

… the party held its state convention to choose delegates to the national convention in Atlantic City

He didn't choose mediocrity; it was conferred on him at birth.

And she urged them to choose that sister after her death, and to promise to preserve that unity forever …

In most Tabaxi tribes, only village elders and those the elders choose as apprentices may use magic.

And that may be a dilemma for the police, who have to choose between alerting the public and apprehending the perpetrator …

It's possible that this is just noise, so that underneath it all, "obliged" and "choose" are good proxies for the cultural qualities that Greenfield wants to trace. But I wonder — suppose we had taken "requirement" vs. "chosen" instead? We would find that "chosen" has fallen as much as "choose" has risen; and "requirement" has risen much more than "obliged" has fallen (raw data here and here):

|

|

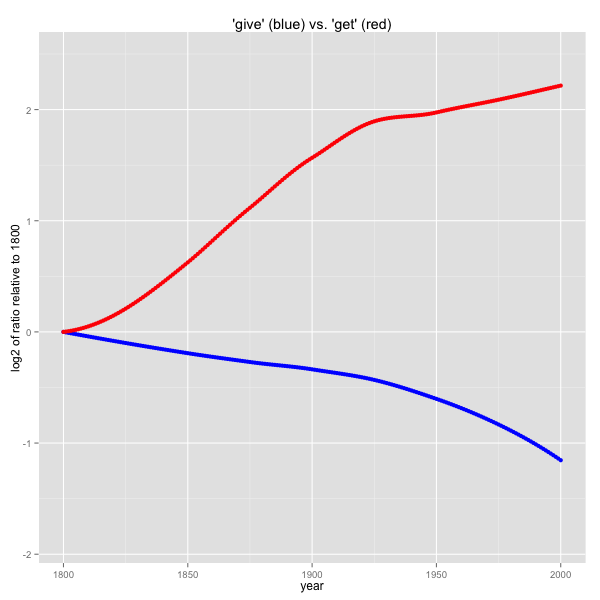

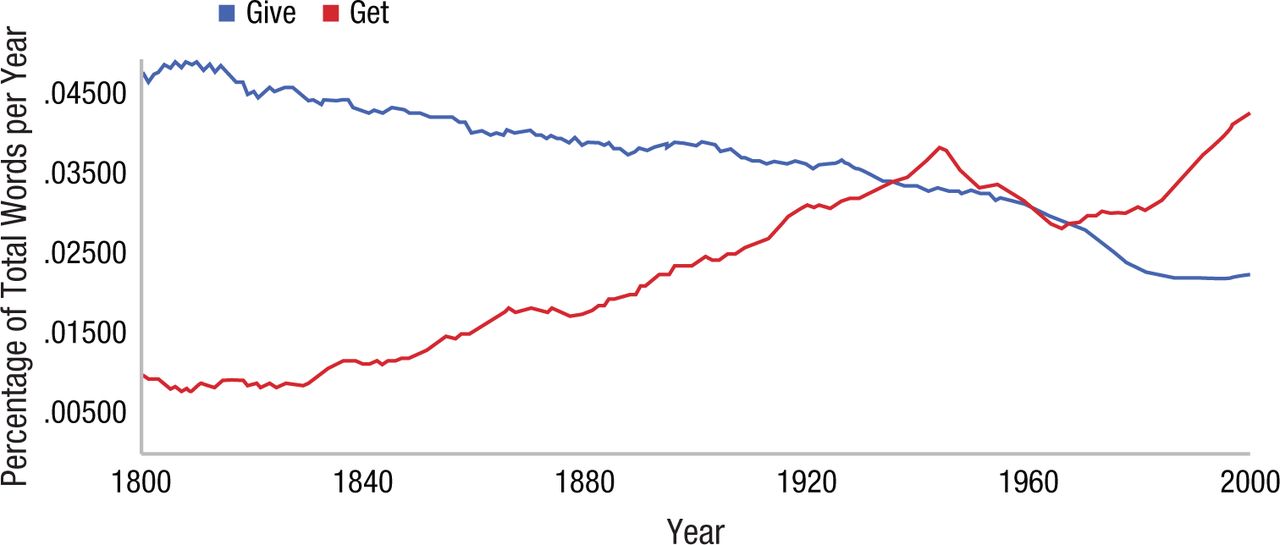

Greenfield's next piece of evidence is a graph of the history of "give" and "get":

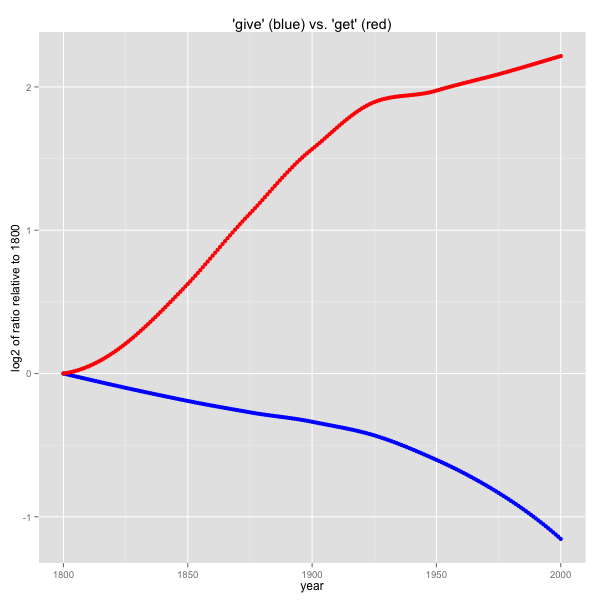

Here's my version:

This comparison is pure PR genius — I'll comment in a later post on where media outlets like CBS This Morning took it — but it has the same problems as the last one, only worse. The words "give" and "get" are even more problematic as proxies for the qualities that Greenfield is interested in, and "get" is an especially bad choice, since it's increasingly used to express change-of-state or simple passive voice ("get acquainted", "get involved", "get married", "get sick", "get rid of", "get out", …), rather than the acquisition of material possessions.

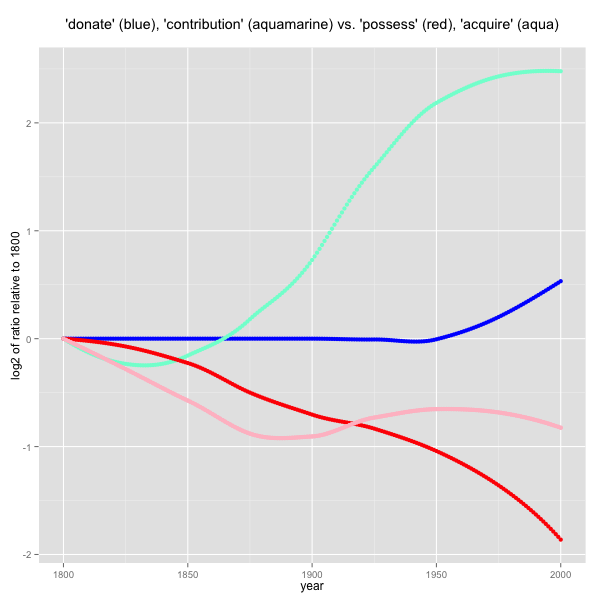

And again, other give-ish words like "donate" and "contribution" have increased more strongly than "give" has declined, while get-ish words like "possess" and "acquire" have gone down almost as much as "get" has gone up:

|

|

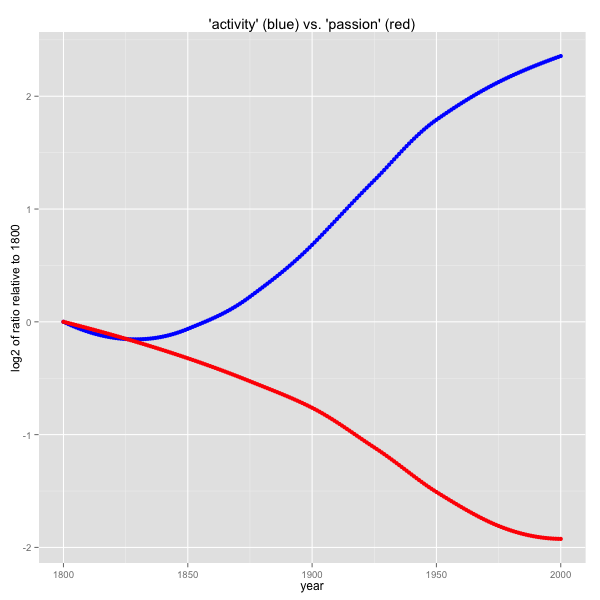

We could similarly match Greenfield's "act" vs. "feel" with "activity" vs. "passion":

|

|

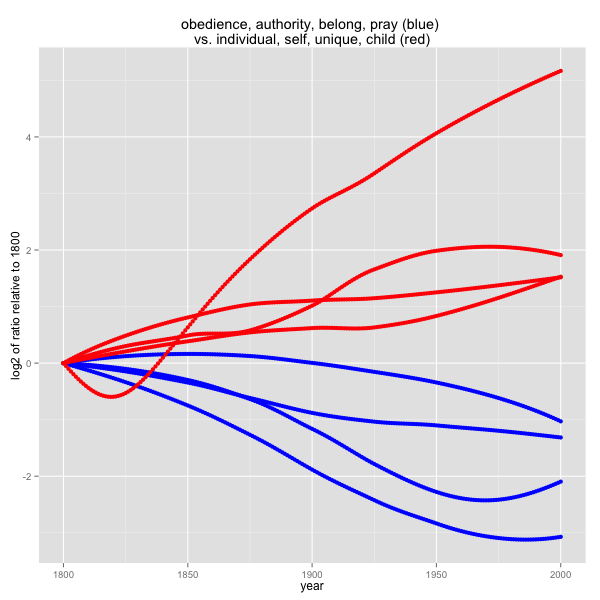

And we could counter her "obedience, authority, belong, pray" vs. "individual, self, unique, child" with "conform, boss, membership, invoke" vs. "singular, my, alone, youth".

|

|

I'm not arguing that her theory is wrong, or that the Google ngrams datasets don't contain supporting evidence. But it's going to take a much more careful and systematic analysis of the lexico-historical data to convince me.

Adrian Morgan said,

August 18, 2013 @ 10:43 am

I was inspired to look at the ngrams for "obey" vs "comply", because they are similar concepts, but "obey" is more "because I say so" whereas "comply" is more "because we're really all on the same side". I therefore expect "comply" to reflect a more modern (liberal) understanding of what authority is.

The results show that "comply" is historically the less common word, but more evenly matched in recent decades. In the American corpus, "comply" overtakes "obey" for most of the 1990s, but only slightly, and "obey" resumes the lead from about 2002. In the British corpus, "comply" overtakes "obey" from the mid 1990s to the mid 2000s, and significantly so, peaking around 2002, but they are evenly matched again from 2006 (ngram data ends at 2008).

This graph shows the ratios.

Ken Brown said,

August 18, 2013 @ 2:55 pm

Britain industrialised and urbanised earlier than the USA (or any other large country)

Is that reflected in the data?

And "get" seems like a very dodgy word to use instudies like this. Far too many uses. "Put" or "have" would be as misleading.

Rosie Redfield said,

August 18, 2013 @ 3:26 pm

The Y-axes to Greeenfield's graphs ('Frequency relative to 1800 (%)') don't make any sense. How can a frequency change by -200%?

Also, are her statements about the requirements of adaptation to rural and urban environments based on good data, or are they really just the predictions of hypotheses, as the preceding sentence implies?.

[(myl) Sorry, those are my graphs, and the confusion is my fault — I wanted rises and falls to be symmetrical, so I took took the log of the ratio, and then since that seemed hard to interpret, I scale the values so that +100 would be a doubling of the value. But the axis label is nonsense, as you point out. I'll fix it at some point when I have a minute.]

Mark said,

August 18, 2013 @ 3:38 pm

Interesting question, easy to explain, flimsy data: Not atypical for PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE. The journal was created with the stated goal of becoming a SCIENCE for psychology. They're pretty much succeeded. It is a "high impact", mediagenic journal, it publishes shallow but attention-grabbing studies, and it has gained a reputation for publishing a lot of unreplicable stuff among people who are also falling all over each other trying to get in. Greenfield's conclusions could be true, we don't know that they are false, and I think that's pretty much what matters, given the "sexy" topic.

D.O. said,

August 18, 2013 @ 5:34 pm

@Rosie Redfield. I wondered about y-axis too. Probably she uses current year as a base, i.e. she graphs (f(year)-f(1800))/f(year)*100%, but I am too lazy to check.

D.O. said,

August 18, 2013 @ 6:12 pm

No, that cannot be it. She wouldn't be able to go over +100% in that case. I am totally lost. Maybe she always uses the smaller number as the base? Anyways, I cannot figure out how she got her "obliged" graph if she actually used the same data as provided by Prof. Liberman under any assumptions.

[(myl) Again, those are my graphs, not hers — you can get hers by clicking the links in the post, e.g. here. The incoherent Y-axis labels on my versions were an unfortunately last-minute brainstorm as I was heading out the door on an errand, as an ill-considered idea about how to make logs of ratios clearer to a general audience. Sorry for the confusion…]

Joseph Pentheroudakis said,

August 18, 2013 @ 6:31 pm

"… developed by the German sociologist Tönnies in the 1800s (1887/1957)". So Tönnies developed those ideas before he was a teenager?

Sloppy sloppy.

D.O. said,

August 18, 2013 @ 6:49 pm

If we really believe in "culturonomics by single word Google ngram counts", it is not clear that urbanization has occurred in the US at all. Frequencies of words "city" and "town" went down and for "farm" and "village" stayed the same.

Brett Reynolds said,

August 18, 2013 @ 8:24 pm

And what about "not obliged", "never felt obliged", "obliged gladly", "happily obliged" etc. The collocations are really important. On the face of it, it would look positive if "hope" were trending up until you look at the collocations and notice that it's all being driven by "lose hope".

Graeme Hirst said,

August 19, 2013 @ 1:37 am

@Joseph Pentheroudakis: In "Tönnies (1887/1957)", 1887 is the publication date, and 1957 is the re-publication date. According to the Wikipedia page on him, Tönnies was born in 1855.

Schroduck said,

August 19, 2013 @ 1:39 am

If these word frequencies really reflect the zeitgeist, where's the rise of socialism in the 19th century? Where's the "Blitz spirit"? Both of these would probably not have been possible without urbanization. There have certainly been periods in the last two centuries when communal spirit was high, and I don't see why city life should be inherently individualistic.

Rubrick said,

August 19, 2013 @ 3:17 am

I find it quite plausible that Ms. Greenfield's study reveals much about the "development of psychological mindedness and the unique self", but that may be because I haven't the foggiest idea what stretch of jargonic gobbledygook is supposed to mean.

Lets You | Poetry & Contingency said,

August 19, 2013 @ 7:53 am

[…] you like playing with Ngrams, and if you have a healthy suspicion of what can be gleaned from them, LL has a recent analysis of Ngrams in a journal paper on "the changing psychology of culture." 18.08.2013 – 11:35 | […]

Nathan said,

August 19, 2013 @ 8:33 am

I was momentarily confused by the fact that your versions of both 'obliged' vs. 'choose' and 'give' vs. 'get' have the colors swapped from Greenfield's versions.

[(myl) Yes, another screw-up on my part. Fixed now…]

Language Log » Stupid FBI threat scam email | Email Scam said,

August 19, 2013 @ 6:56 pm

[…] The culturomic psychology of urbanization | The New York Post goes verbless […]

David said,

August 19, 2013 @ 7:11 pm

Regarding the y-axis: not such a bad idea, with a little relabelling. Check out Tornquist, Vartia, and Vartia, "How should relative changes be measured?"

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00031305.1985.10479385#.UhKzgT8kVCo

millou said,

August 19, 2013 @ 8:41 pm

thank you Mark for this commentary!

I've read the study (a mere 11 pages, references included) and it appears that Greenfield takes for granted the following series of correlations:

1. urbanization is correlated with the valuation of individualism and devaluation of community spirit (based on an admittedly "ideal" model, so we already have some amount of statistical smoothing taking place here)

2. the literature of any given period reflects the contemporary mainstream values to a measurable extent (disregarding the possible influences of contradictory or unrelated currents of thoughts)

3. the predominance of said values manifests itself directly in the print frequency of words correlated with them (and the corollary of this assumption is that semantic context does not matter, not even the most basic collocations; as noted by Mark Liberman and others in the comment feed, a study of the words in context begins to paint a much more nuanced picture)

4. as pointed out by Mark Liberman, the word pairs are not questioned: that the use of "obliged" is strongly correlated with ("indexes" is the word Greenfield uses) communal values while "choose" indexes individualistic values is part of the bundle of hypotheses – unless the correlations were retro-fitted to the hypotheses as Mark's counter-examples suggest.

Besides these assumed correlations, there are a few more work hypotheses which weigh negatively on the statistical legitimacy of the results:

5. "ecological change" (from rural to urban environments) is the dominant driver of change in the frequency of the "index" words – other possible (socio)linguistic variables are not discussed (Greenfield does try to confirm the tendencies found for each of her pairs by repeating the search with a synonym pair chosen – at her discretion, it must be assumed – from Roget's Thesaurus.)

6. Google's corpus is adapted to this specific study. i.e. Greenfield assumes that Google's sample is big and broad enough to allow the 'zeitgeist' of a given period to be extracted from it – or to put it otherwise, massive enough to compensate for the summed statistical errors of the approximate correlations. as a mathematical problem, however, that is beyond my means.

7. her choice of British literature over the same period as a "test corpus" destined to reproduce and confirm the findings of the US corpus is odd: there are obvious common points between the two countries that might cancel out the ecological correlation Greenfied sets out to prove. for instance, er, they use the same language. and they have many cultural ties. ideas circulate very quickly between UK and US. this is especially problematic as the author uses this "replication" as a final proof of the soundness of her method:

"The replication of U.S. findings with British books shows that the predicted results are not dependent on a particular national context or a particular set of books. This replication constitutes strong evidence for the generality of the theoretical model and, more specifically, its cross-national generalizability"

I'd like to see her try with a Japanese, Russian, Argentinian corpus. honestly, I would.

8. finally it does not appear that P. Greenfield adjusted her findings to the fact that more print, at any given time, is put out by city-dwellers – and upper-class city-dwellers at that – than by countryfolk. but i suppose it could be argued that this being a constant factor (though that remains to be proved), it may be safe to disregard it… as long as it is acknowledged. To put it more generally, the demographics of the producers of "cultural products" are not deemed to impact the validity of the findings.

some of these assumptions are stated – unapologetically -, others go unacknowledged.

I'll point out a final methodological flaw. Greenfied's reasoning is a logical loop, as she makes the soundness of her hypotheses depend on her results:

"In summary, as the U.S. transformed from rural to urban between 1800 and 2000, culture, as reflected in more than a million American books, also transformed. With parallel social change occurring in the United Kingdom, the replication sample of British books revealed similar culture change over this period of time. These findings signify that books as cultural products reflect human ecology. They also signify that cultural features can be indexed by word-use frequencies, which, in turn, reflect what is prioritized by a population. "

"word-use frequencies […] reflect what is prioritized by a population"… wasn't that a prerequisite to the whole study?

to be fair, Greenfied does state in the introduction that

"The goal of the study was to demonstrate that, as the United States moved ever further in the gesellschaft direction, gesellschaft-adapted cultural features […] showed a quantitative increase, whereas gemeinschaft-adapted cultural features […] showed a quantitative decrease."

but that bypasses the whole chain of correlations i mentioned. you've got two phenomena and one huge corpus of words and you somehow decide that the tendencies you find in the latter prove a definite link between the formers. Nor should one be fooled by the interjected putative link: "These findings signify that books as cultural products reflect human ecology." That books reflect human ecology is too general and not relevant enough a statement to be meaningful here. Of course books "reflect human ecology". but P. G. has not "proved" this by studying the evolution of a handful of words within 2 centuries of a complex history, which includes – among many other phenomena – a definite trend of urbanisation. as for the "word-use frequencies […] which, in turn, reflect what is prioritized by a population" it is a worthless statement, with nothing whatsoever to back it up – only Greenfield's conviction.

either you believe beforehand that word-frequencies of 1-grams in the literature of a country can be directly traced to the human ecology of the same country, and you proceed on that basis to demonstrate something else (but you don't expect to be taken very seriously); or you set out to prove that link carefully. you can't just fish that correlation out of nowhere, do one afternoon's worth of research using Google Ngram and the Roget and then publish a paper saying you've proved that link exists.

A final passage of the paper, just for kicks:

"The contrast between contributing to the welfare of other people and obtaining something for oneself was indexed by “give” and “get.” The prediction was that, as urban populations expanded, the relative frequency of “give” would decrease and the relative frequency of “get” would increase. Figure 3 confirms this hypothesis: “Give” became less frequent, and “get” became more frequent, between 1800 and 2000. However, there was also short-term deviation from this pattern between 1940 (entry of the United States into World War II) and the 1960s (civil rights movement). During that period, the frequency of “get” declined as well, perhaps reflecting a decline of self-interest motivation during World War II and the civil rights movement. “Get” starts to rise again in the 1970s, perhaps because of the onset of the women’s movement. The 1970s are the point at which the final crossover takes place, with “get” becoming more frequent than “give” from that time until the final year studied, 2000. The important point is that, over the long haul, “give” declines whereas “get” increases in relative frequency, correlated with increasing levels of urban residence, as predicted."

oh but of course. there's less gets and more gives in the 40s due to a… decline of self-interest motivation during WW2. and gets go on the rise again as women start demanding they "get" abortions and birth control pills. and wow, I had never realised that the civil rights movement was a "give" trend while women's rights was a "get" one!

anyway, good thing she didn't conduct this study in 1970, she might have had to mitigate her initial hypothesis due to the statistical glitch caused by all this "benevolence" and "obedience" sparked by the war and the solidarity obviously "indexed" by the "cultural products" towards the African Americans humbly asking for a bit of "giving".

i could conclude with a rant about the hubris of datafication, but i've made my point i hope.

Life on the island: Is the digital age enabling a disturbing rise in hyper-individualism? | pundit from another planet said,

October 1, 2013 @ 3:57 pm

[…] The culturomic psychology of urbanization (languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu) […]

Google’s Ngram Viewer Goes Wild | TokNok Multi Social Blogging Solutions said,

October 17, 2013 @ 8:45 am

[…] relative to give, does that mean we're becoming more selfish? As Mark Liberman suggested on Language Log, the rise in get usage could be due to phrasal patterns that have nothing to do with acquiring […]