Why isn't English a Bar Mitzvah language?

« previous post | next post »

In response to my post on the relative difficulty of learning to read in English ("Ghoti and choughs again", 8/16/2008), Mark Seidenberg sent a note raising an interesting question about the relationship between writing systems and the morphology of the languages they represent:

It is my informal observation that the shallow orthographies are associated with languages that have relatively complex morphology (inflectional and/or derivational). Classic examples would be Serbo-Croatian, Russian, Finnish and German (though of course these languages aren't all morphologically complex in the same way). I mean complex relative to other languages like English. The deep orthographies are associated with languages such as English and Chinese, which have relatively simple morphological systems. Perhaps this observation is correct (though mixed systems such as Japanese present a potential challenge); perhaps your readers would be able to generate counterexamples. Still, if the general trend holds, the question would then be why properties of the writing system trade off against properties of the language.

I'm not sure whether the generalization is really true — Japanese, for example, certainly does look like a morphologically-complex language whose standard written form is anything but phonologically shallow. But if the generalization were true, I'd be tempted to try a functional explanation as follows. In speech, quite a bit of homophony (different morphemes being pronounced the same way) is tolerable, because prosody and context usually make it clear enough how to put morphemes together syntactically and how to interpret them. In writing, though, a corresponding amount of homography (different morphemes being written the same way) is more problematic, because the prosodic clues are missing; and therefore some phonologically-opaque differentiation of the written form of words is helpful. In a morphologically complex language, this motivation is reduced, because the inflections continue to provide high-redundancy clues about how to fit the morphemes together syntactically, so that there's less reason to create (or preserve) arbitrary differences in how to write them.

Note that this hypothesis doesn't make any claims about the relative (or absolute) amounts of homophony (or redundancy), so it's not easy to disprove. But I'd caution that (as a matter of practical experience) post hoc functional explanations rarely hold up, at least in linguistics. And the social history of orthographic systems is so full of apparently-arbitrary top-down political choices that it's hard to see how functional pressures (even if real) could have a consistent evolutionary impact.

Mark half-seriously suggests an alternative functional explanation, in terms of a sort of conservation of learning difficulties:

A related issue: reading researchers look at reading. But, what is happening with the children's spoken language acquisition? Serbian speakers get the spelling-sound correspondences essentially for free, because they are highly consistent. It would be a good bar mitzvah language. However, the inflectional system is very complex and speakers continue learning it well after the spelling-sound correspondences are second nature. So my question for people who find differences in ease of learning to read is: what is the state of the child's knowledge of the corresponding language? Maybe it's a good thing that Finnish orthography is shallow: the children can then spend a little extra time mastering the spoken language.

By "a good bar mitzvah language", Mark means a language whose written form is easy to learn how to recite, whether or not you understand any of it or even recognize the words. This is a reference to the fact that some Jewish children learn only enough Hebrew to be able to read a Torah or Haftarah passage out loud at their bar mitzvah (or bat mitzvah) ceremony. If the diacritical signs representing vowels are present, written Hebrew is phonologically transparent enough that it's fairly easy to learn to read it in this way, without knowing much (or even any) of the language. (And the cantillation signs provide a stylized form of phrasing and intonation…) Mark's point is that it's also easy to learn to "recite" Serbian, in this sense of pronouncing the written form (though obviously with an accent if you're not a native speaker [– and minus vowel length and word accent, according to Boris Blagojević's comment below]). It's much harder to learn to recite English (or Chinese) .

Returning to the question of the relative difficulty of learning to read English in a more general sense, Mark observes that

The key paper here is by Nick Ellis, now at Michigan, comparing learners of Welsh and English, which differ in orthographic depth. Welsh, shallow, wins. But, the question is, what was the state of their knowledge of Welsh vs. English grammar?

That's Nick C. Ellis and A. Mari Hooper, "Why learning to read is easier in Welsh than in English: Orthgraphic transparency effects evinced with frequency-matched tests", Applied Psycholinguistics 22: 571-599, 2001. The abstract:

This study compared the rate of literacy acquisition in orthographically transparent Welsh and orthographically opaque English using reading tests that were equated for frequency of written exposure. Year 2 English-educated monolingual children were compared with Welsh-educated bilingual children, matched for reading instruction, background, locale, and math ability. Welsh children were able to read aloud accurately significantly more of their language (61% of tokens, 1821 types) than were English children (52% tokens, 716 types), allowing them to read aloud beyond their comprehension levels (168 vs. 116%, respectively). Various observations suggested that Welsh readers were more reliant on an alphabetic decoding strategy: word length determined 70% of reading latency in Welsh but only 22% in English, and Welsh reading errors tended to be nonword mispronunciations, whereas English children made more real word substitutions and null attempts. These findings demonstrate that the orthographic transparency of a language can have a profound effect on the rate of acquisition and style of reading adopted by its speakers.

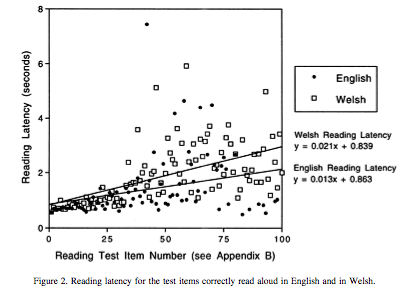

Ellis and Hooper show some interesting effects beyond percent correct, such as an apparently-paradoxical difference in overall latency (how long it took to read a word) and in the slope of the function relating latency to (word) frequency:

The naming latencies for correct responses are shown in Figure 2, which plots the mean reaction times (RTs) for each frequency-matched pair of English and Welsh test items from item 1 (frequencies > 54,000 per million) down to item 100 (frequencies = 1 per million). Note that this is a graph of the main effects of frequency and language; the individual data points reflect a wide variety of other lexical influences, including word length, imageability, orthographic regularity, and sound – spelling consistency. Overall, the latencies are greater for Welsh than for English: English M = 1.41 s, SD = 1.13; Welsh M = 1.85 s, SD = 1.11; t(82) = 2.70, p < .01, and, as can be seen in Figure 2, the difference between the two groups increases as an inverse function of word frequency.

Why were the children tested in English "faster readers", on average, given that the children tested in Welsh were "better readers" as judged by the percent of test words correctly read? Ellis and Hooper give this explanation:

… it should be remembered that there are fewer correct responses in the English group; indeed there were 17 words for which there were no correct responses for the English group (hence the df of 82). Thus, the Welsh function is penalized by the presence of a greater number of low-frequency data points for Welsh. Over the 30 most frequent items in the languages for which there was, on average, greater than 95% accuracy of responding in both groups, there was no significant difference in the latency of responding… Over the next 30 items (31 – 60), on which responding was 42% correct in the English group and 50% correct in the Welsh group, the latencies were still not significantly different in the two groups… It is only in the last bin of 40 items (61 – 100) that the latencies differed significantly: English M = 1.734 s, SD = 1.13; Welsh M = 2.26 s, SD = 0.93; t(22) = 2.5, p < .05, on the 23 word pairs where there is some correct naming in both groups, although English accuracy was only 6.8%, whereas Welsh accuracy was 17.3%.

Mark's note also argues for applying a consistent psychological model of reading across types of orthographic system:

… there is a lot of research now, like Seymour's, suggesting that English is harder to learn to read than some other writing systems. There is a recent article in Psych Bulletin by David Share suggesting that reading research has been thrown off by its emphasis on English, which he believes is highly atypical. I think he's missed the boat. People's brains are alike. There are only so many ways to read. You want a general theory out of which differences between writing systems fall out. Whether English is "typical" or not depends on how you do the normative comparison. That's what our models attempt: ithere's one architecture (determined mainly by the nature of the reading task and how it relates to spoken language), and one set of principles about how knowledge is represented, learned, processed, etc., There are then differences across writing systems in the "division of labor" between components. So it's easy to place English in a broader context that includes other writing systems.

The article that Mark mentions is David L Share, "On the Anglocentricities of current reading research and practice: The perils of overreliance on an 'outlier' orthography", Psychological Bulletin 134(4) 584:615, 2008.

Mark's own proposals can be found in various papers in his publications list, for example in M.S. Seidenberg and D.C. Plaut, "Progress in understanding word reading: Data fitting versus theory building", In S. Andrews. (Ed.), From inkmarks to ideas: Current issues in lexical processing, 2006.

Boris Blagojević said,

August 19, 2008 @ 10:13 am

Just a short note on Serbian: reading it correctly would be something achievable only for a fluent speaker, since neither the type of accent (rising/falling), nor vowel length (distinctive in accented and post-accent syllables) are marked in writing.

It would actually be a lot easier to learn how to write it.

Cliff Crawford said,

August 19, 2008 @ 10:39 am

I'm not sure if Japanese is really a counterexample. While the main source of its orthographic complexity is all of the different readings for the kanji characters, the morphologically complex parts of the language (the verb inflections) are always written in kana, which are orthographically shallow.

Ryan Denzer-King said,

August 19, 2008 @ 12:29 pm

In Ellis & Hooper, is it not significant in any way that one language group was monolingual while the other was bilingual?

Joe said,

August 19, 2008 @ 1:13 pm

It's odd to hear about English being so difficult to learn, because I learned to read just like I learned to talk and I don't really remember either process. To me, it feels as though I have always known how to read, though I'm sure I just learned from my parents when I was rather young.

Now, learning to *spell* on the other hand…

kyle said,

August 19, 2008 @ 1:26 pm

i don't think japanese is a counterexample because i don't think literate japanese speakers learn to write something that is equivalent to japanese. they learn a chinese-based code which assumes at least some implicit knowledge of chinese.

this is backed up by the critique by (writing systems scholar) j. unger:

http://www.ling.upenn.edu/courses/115/readings/Unger1987.html

where he argues that japanese literacy is rather low for this reason. also, see william hannas' book "the writing on the wall", which is sort of a reductio ad absurdum of such airs:

http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=940CE6DD143CF930A35756C0A9659C8B63

pm215 said,

August 19, 2008 @ 5:26 pm

Japanese kana were of course less orthographically shallow before the post-WW2 spelling reform; I don't know enough about the pre-war kana usage to know how far into the deep end it took the orthography, though.

nascardaughter said,

August 19, 2008 @ 7:02 pm

It's interesting to think about what is meant by "reading." Is it about decoding, or comprehension, and how much, and under what circumstances, can those two things be separated?

Related to those questions, it might be useful to consider logographic writing systems as well… With practice, reading of phonological representations seems to come down to a similar kind of visual recognition of the shape of a word — I imagine this is true even for shallow orthographies (?)

Does learning to decode faster initially indicate that one has acquired an advantage in terms of learning to read, lifelong reading skills, etc.?

Alex said,

August 19, 2008 @ 7:05 pm

Where would Arabic (or similar consonantic systems) fit in this scheme? The Arabic writing system is, in a way, very shallow. As long as you stick to the consonants, you can read exactly as it is written. On the other hand, without a grasp of the grammatical structure, it is impossible to vocalize the words.

Stephen Jones said,

August 20, 2008 @ 1:39 am

I think there is a much simpler historical explanation. English has a relatively simple morphology because the French speakers didn't grok the Old English.

It also has complex orthography because words come from a variety of languages where they are pronounced differently. It's beyond me what Mark's correspondent means when he says Chinese has deep orthography.

Stephen Jones said,

August 20, 2008 @ 1:40 am

On the other hand, without a grasp of the grammatical structure, it is impossible to vocalize the words.

As far as reading the Quran goes, they always put the short vowels in.

Kate L said,

August 20, 2008 @ 9:10 am

My husband is Finnish and our seven year-old daughter is an accurate and fast reader in English. When reading in Finnish however, she gets words wrong because she tends to read the start of each word and then guess the rest according to the context. This strategy plainly serves her well for reading in English but is disastrous when applied to Finnish, as the sense often depends on the case endings at the ends of the words. Her father then accuses her of not reading "properly" as she is not thinking about every single letter, something which she doesn't have to do for English.

This would probably be different if we had taught her to read Finnish in the way they do in Finland, but if we lived there, she wouldn't have started school yet.