Vietnamese in Chinese and Nom characters

« previous post | next post »

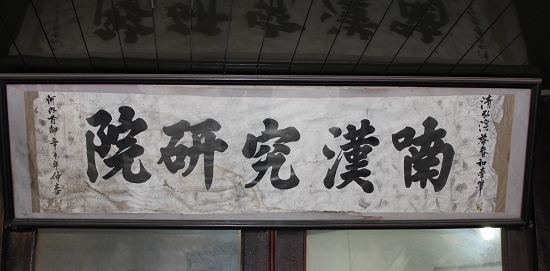

The Dōngfāng zǎobào 东方早报 (Oriental Morning Post / dfdaily) (May 26, 2013) carried an article entitled "Dāng rénmen dōu xiě Hànyǔ shí" 当人们都写汉语时 (When everyone writes Chinese) that begins with the following photograph:

Any literate speaker of one of the Chinese languages is going to look at that and get a headache. Their head will spin. They won't know whether to begin from the left or right. They will experience severe cognitive dissonance. They may get angry. They may say that stupid Vietnamese do not know how to write Chinese. They may want to trash the sign, like the Communist Party official who missed his plane in Yunnan (not too far from Vietnam!).

What does the sign really say?

If we try to read it in Mandarin from left to right, it would be:

–> yuàn yánjiū hàn nán 院研究漢喃

(courtyard research Sino-Nom)

— that doesn't make much sense.

If we try to read it in Mandarin from right to left, it would be:

yuàn yán jiū hàn nán 院研究漢喃 <–

(Nom-Sino XX [next two characters don't compute in that sequence] courtyard)

— that makes even less sense.

Before proceeding, I'd better explain what Nom 喃 is. Nôm or chữ nôm is a vernacular script that was used to write Vietnamese during the 15th to 19th centuries. Based on Chinese characters employed in a variety of creative ways, but also including many invented characters, nôm was used to write popular literary works in Vietnamese language, while Literary Sinitic / Classical Chinese was reserved for more serious purposes. The graph 喃 for nôm itself is a good example of how new characters were devised: Mandarin nán 南 ("south") has a little "mouth" radical added to the upper part of the left side, resulting in a new character that is intended to specify the writing system we know as Nom. Of course, it has absolutely nothing to do with "south" or "mouth"!

Now let's read it in Vietnamese from left to right as it is intended:

Viện nghiên cứu Hán Nôm 院研究漢喃

("Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies")

Literally:

The Han-Nom Research Institute

From the point of view of meaning:

The Institute for Research on Classical Chinese (i.e., Han) and Vernacular (i.e., Nom) [Documents {implied}]

Here's the website for the institute, and here's a Wikipedia article about it.

I asked three specialists on Vietnamese for their views on the wording of this sign.

Bill Hannas:

If you read right to left in the old (formal) way of writing Chinese horizontally, the 研究 (nghien cuu) would be reversed, which is the only invariable in the expression. So you have to read left to right. The question is what language (or script) is it?

It surely isn't (classical) Chinese. The word order (noun + adjective) is indeed Vietnamese and "vien nghien cuu" is a proper lexical item. But my guess is the institute is using Nom, not some newly contrived way to make Vietnamese readable with Chinese characters.

Of course, that's exactly what Nom was meant to do, so this may be a distinction without a difference.

Liam Kelley:

It makes sense, but I think it was probably somewhat of a nationalist decision to write it that way. Probably 90% of what that place holds (manuscripts, rubbings of inscriptions) are in what they call Han (classical Chinese). In the past, when classical Chinese was used, I think any official entity would have recorded its name in the classical Chinese order (and this continued in the South to some extent after 1954). So by writing it in this way they are trying to make a modern "Vietnamese statement."

N.B.: By "classical Chinese order", Liam means hàn nán yánjiūyuàn 漢喃研究院 ("Han-Nom Research Institute").

Steve O'Harrow:

Liam has, as usual, hit the nail right on the thumb. But while "nationalist," it is also good Vietnamese syntax. And, after all, it IS their language. It's very much in accord with the cadence of the language as it is spoken in Viet Nam today.

In other words, "it feels right." The rhythm of this modern language [in Viet Nam itself, and NOT in Orange County] is different from what it was only a few decades ago. As with all living languages, there are running changes – [Viet Kieu language teachers in the US, Australia, and Europe teach the idealized language of their youth].

[VHM: Viet Kieu are ethnic Vietnamese living outside of the country.]

A good example of this kind of thing is the politically correct tendency to try to rid English of "-man" at the end of words like "chairman," in the mistaken assumption that "man" here means "male." But the historical meaning of the suffix in English is actually "person." However, because most modern speakers of the language are supremely ignorant of etymology [as are most Frenchmen, Chinese, Danes, and Solomon Islanders, and anybody else you can think of], they've succumbed to the "correct" usage of "chairperson" or, now, simply "chair." [ I was a departmental "chair" for a while and I insisted that I felt more like a "footstool."].

The point is that now it "feels" right to think that "gay" has to mean homosexual and not "light-hearted" [pity author Gay Talese, as he laughs all the way to the bank]. So it has become with Vietnamese: it feels correct to say "Viện Hán Nôm" and 'Công hoà Xã hội Chủ nghĩa" and "Khoa học Xã hôi," even if the original in Chinese was in different order.

They say Chinese is the Latin of the East but Italians don't speak Latin [a related language] and Vietnamese certainly don't speak Chinese [an unrelated langauge].

These are the expressions referenced in Steve's penultimate paragraph:

"Viện Hán Nôm" = 院研究漢喃

("Institute Hán-Nôm", i.e., Hán-Nôm Institute")

"Công hoà Xã hội Chủ nghĩa" = "Socialist Republic"

as in "Công hoà Xã hội Chủ nghĩa Việt Nam"

[Socialist Republic of Viet Nam — 共和社會主義越南]

Cf. Mandarin Yuènán shèhuì zhǔyì gònghéguó 越南社會主義共和國 with the same meaning.

"Khoa học Xã hôi" = "social science"

as in "Trường Đại học Khoa học Xã hội và Nhân văn"

[University of Social Sciences and Humanities — 場大學科學社會吧人文]

NOTA BENE : 吧 ("and") here is a "nôm," i.e., "vernacular," character, read for phonetic value alone, but well understood in the Vietnamese spoken context

Cf. Mandarin Shèhuì kēxué yǔ rénwén dàxué 社會科學與人文大學 with the same meaning, though I think it would sound more natural to read it Rénwén yǔ shèhuì kēxué dàxué 人文与社会科学大学.

In all of these cases, we see that the modifiers are piled up after the head noun in Vietnamese, but before it in Mandarin.

For what might happen if we tried to write English in Chinese characters, I recommend John DeFrancis' delightful "The Singlish Affair", a chapter in his The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy.

[h.t. Wicky Tse and thanks to the three Vietnamese experts]

maidhc said,

May 29, 2013 @ 5:27 am

south+mouth makes sense to me. Vietnam is south of China, and it's a representation used to record spoken literature like poetry.

I recall a few years ago there was a project to collect poems from ordinary people in Vietnam, and there was an amazing amount of material collected. Long sophisticated poems recited by regular people. The results were published in a trilingual edition: nôm, Vietnamese and English. According to the NPR report there were only a handful of people who could read nôm any more. You would have to be fluent in both classical Chinese and Vietnamese just to start on it.

It seems like an excellent idea to have an institute to preserve and study this material. Here's another article: http://www.vietnam.com/article/saving-ancient-vietnamese-script-ch-nm-from-total-extinction.html

Now I'd like to find that collection; a quick search doesn't turn up much.

Gpa said,

May 29, 2013 @ 7:08 am

Chu nom was created for the Vietnamese language based on how Chinese characters were created. Mostly phonetic and sematic. Chu nom has been out of use but some people are trying to preserve it because with the Latin alphabet it's still confusing when you can't input the diacritics on some computers with Quoc Ngu.

Gpa said,

May 29, 2013 @ 7:09 am

sematic should be "semaNtic"

Gpa said,

May 29, 2013 @ 7:18 am

Viet Kieu is based on Chinese via Cantonese dialect 越僑 "Yuet Kiu". 越僑: 越 南的(Chinese meaning "of or from Vietnam") + 僑 ( Chinese word meaning "overseas", as in 華僑, meaning "Overseas Chinese"). So from Chinese 越僑, it means "Vietnamese people who are living overseas". Without the Chinese language, there'd be no such meaning. And to say that it's from Vietnamese is incorrect. The Vietnamese do borrow from Chinese and use Vietnamese word order, so it doesn't look like the original Chinese.

Gpa said,

May 29, 2013 @ 7:33 am

院研究漢喃. This is copying a type of calligraphy which tries to make it look like it's in Chinese word order (anything written in Chinese before 1970 would be in the right to left order, if written horizontally):

Reading from right to left, it means literally "Nom-Han Research Institute", not "Sino-Nom Research Instutute".

Han refers to the Chinese script in any style, whether it's in Kaishu, Lishu, etc…, and not just referring to what Westerners called Classical Chinese which really just is a misnomer.

Gpa said,

May 29, 2013 @ 7:38 am

south+mouth makes sense to me. Vietnam is south of China, and it's a representation used to record spoken literature like poetry.

喃 – Definition: Vietnam/Vietnamese.

The mouth radical means it's a made up character, much like most of the characters made up for & in Cantonese.

南 is short for 越南.

It has nothing to do with China.

Gpa said,

May 29, 2013 @ 7:40 am

really just is a misnomer. should be "is really just a misnomer."

Gnoey said,

May 29, 2013 @ 7:47 am

I am a native Chinese speaker, and I read your article on Chu Nom with interest.

Just to give my two cents' worth, 喃 (nan2) is a legit Chinese word, not really a Vietnamese invention, which means "to mumble". It is usually used in the idiom 喃喃自语 (nan2 nan2 zi4 yu3), which means "to mumble to oneself", and the compound 呢喃(ni2 nan2), which also means "to mumble, to talk softly". These expressions are still in common use.

Gpa said,

May 29, 2013 @ 7:54 am

Viện Hán Nôm = literally 研漢喃 and doesn't make sense. 研, Viện, is rarely by itself. From right to left, 漢喃 means "Nom-Han", not Sino-Nom/Han-Nom, etc…

Sorry. I just saw that 院研究漢喃 has 研究 in the left to right word order via Chinese. If studying Classical [lack of a better word] Chinese, the Vietnamese calligraphers should follow through with 院究研漢喃, instead of 院研究漢喃.

Because 研究 (left to right)/ 究研(right to left) they should follow either one but be consistent being that it's not originally Vietnamese but from Chinese.

Much like 平和 is "peace" in Japanese due to their direct borrowing of Chinese via right to left writing(pre-1970), and even though they now use left to right horizontal writing, they still use the "backward"/"reversed"/"mirrored"/"incorrect" way of writing it in Kanji. But in Chinese, it's 和平(left to right)/平和(right to left) horizontal writing.

julie lee said,

May 29, 2013 @ 8:55 am

I really got dizzy with @Gpa's last comment. Pretty early here (north of Golden Gate Bridge).

7 a.m.

Joe said,

May 29, 2013 @ 9:39 am

Could the Vietnamese translation be a kind of creole here? The transposition of characters reminds me of the creole phrase "Laissez Les Bons Temps Rouler" which sounds horrendous in French but is a commonplace in Louisiana.

Faldone said,

May 29, 2013 @ 10:16 am

I'm going to use that first chance I get.

michael farris said,

May 29, 2013 @ 10:21 am

"Could the Vietnamese translation be a kind of creole here?"

I don't think so, the point is (to simplify some syntactic typology) that Vietnamese is a very strongly head initial. Chinese is kind of mixed but mostly head final (Japanese and Korean are strong head final languages). This means that while the natural order in Chinese is modifier head (big house), the natural order in Vietnamese is head modifier (house big)

The result is that the language is full of lexical items which semantically (to the extent that they are perceived as individual morphemes) are out of whack with the natural order of elements in the language (maybe a bit like Ottoman Turkish which was full of persian constructions that didn't follow natural Turksih order).

New compounds made from Vietnamese (or Sino-Vietnamese) elements tend to follow Vietnamese order and sometimes (seemingly randomly) Chinese elements get re-ordered in Vietnamese as well.

michael farris said,

May 29, 2013 @ 10:25 am

"some people are trying to preserve it because with the Latin alphabet it's still confusing when you can't input the diacritics on some computers with Quoc Ngu."

I can think of lots of reasons to study and preserve Nom texts and even generate new texts in Nom (so that it's not only a museum piece) but the idea that Nom would be a more practical (!) alternate for quoc ngu when the diacritcs are unavailable isn't among the first….. any of them.

J.W. Brewer said,

May 29, 2013 @ 10:35 am

I am somewhat confused by Steve O'Harrow's point suggesting significant changes in Vietnamese syntax just within the last few decades which have not been followed (or are at least subject to prescriptivist peeving) in the diaspora. Most others commenting seem seem to suggest to be that one order of characters makes natural sense for Han and the other for Nom (with both word orders being comparatively stable over time or at least in the last century or two), with the difficulty coming because these are essentially different languages written with the same characters and there has been sociolinguistic change as to which would be deemed appropriate to be used in this sort of context. Maybe this could be harmonized via Michael Farris' suggestion that Vietnamese i(whether spoken or written in Nom) has traditionally included some compound-word lexical items whose internal ordering followed Chinese principles and that (if I'm reading him correctly) sometimes older such compounds get taken apart and then have their component morphemes reassembled in a different order? Has that plausibly happened with the name of this particular institution (as one would refer to it in spoken Vietnamese)?

For a less exotic parallel than Ottoman: since once upon a time many centuries ago Anglophones were subject to a Francophone ruling class, the English lexicon of government and administration still has a stratum of compound nouns that follow French order with the adjectives postposed rather than preposed to the head noun. Attorney general and court-martial are good examples. This often creates confusion when, for example, trying to inflect them as plurals.

julie lee said,

May 29, 2013 @ 12:56 pm

@J.W.Brewer,

Thanks for explaining the historical reason for the word order of attorney general and court-martial.

Gpa said,

May 29, 2013 @ 5:29 pm

"喃 (nan2) is a legit Chinese word".

I won't say it's legit, but rather that it's created with a somewhat different meaning than the one used in Chu Nom.

喃 (nan2) used in Mandarin is what's called "onomatopoeia" in English, using a word from Greek origin.

Bathrobe said,

May 29, 2013 @ 6:22 pm

Julia, you can ignore Gpa's comments because he just exemplifies what Professor Mair said: "Any literate speaker of one of the Chinese languages is going to look at that and get a headache. Their head will spin. They won't know whether to begin from the left or right. They will experience severe cognitive dissonance."

In Gpa's case, he insisted on thinking that it was Chinese written old style (right to left), until he noticed — too late — that the characters in the word 研究 would be in the wrong order. (He also says that Viện Hán Nôm (研漢喃) doesn't make sense. Well, of course it doesn't make sense. Viện Hán Nôm should be written 院漢喃).

Steve O'Harrow may be a knowledgeable guy, but the quote certainly doesn't do him justice. It's hard to see where he's coming from in that string of hobby horses. In the end it's hard to figure out who is supposed to be confused by Công hoà Xã hội Chủ nghĩa Việt Nam, the Chinese, or the Vietnamese in Orange County.

Professor Mair's comments are (as usual) spot on. So is Liam's pointing out that this is a very modern, nationalistic use of Chữ Nôm. At the time Chữ Nôm was actually used by the Vietnamese, such a sign would probably have been in Classical Chinese. And Michael Farris is correct in pointing out the huge number of Chinese borrowings into Vietnamese that follow the Chinese order, not the natural native order of Vietnamese (for which J.W. Brewer gave a good analogy in English). So the elements in the word 研究 (nghiên cứu) are in the Chinese order, but the whole expression Viện nghiên cứu Hán Nôm (院研究漢喃) follows the natural Vietnamese order.

(Incidentally, the Vietnamese will insist that nghiên cứu is two words, not one, which confuses matters a bit. Basically nghiên cứu acts like a single word in Vietnamese).

Victor Mair said,

May 29, 2013 @ 6:51 pm

Bless you, Bathrobe!!

Drago said,

May 29, 2013 @ 7:18 pm

David Mortensen and Patrick Littell wrote a nice problem on a related topic for NACLO:

http://www.naclo.cs.cmu.edu/problems2010/N.pdf

Enjoy.

Matt said,

May 29, 2013 @ 8:01 pm

As a kanbun enthusiast, it seems to me that the obvious solution is to read it from right to left, but to add tiny numbers indicating that 漢喃 and 研究 are to be read as units, thus providing the rearrangement 漢喃研究院. There, problem solved. If anyone needs me, I'll be in my stateroom pronouncing "而況於…乎" "shikaru o iwanya … ni oite o ya."

Matt said,

May 29, 2013 @ 8:39 pm

Oh, also:

Much like 平和 is "peace" in Japanese due to their direct borrowing of Chinese via right to left writing(pre-1970), and even though they now use left to right horizontal writing, they still use the "backward"/"reversed"/"mirrored"/"incorrect" way of writing it in Kanji.

No, 平和 was almost certainly taken directly from Chinese, long before horizontal writing of any sort was widely adopted anywhere in the CJK-o-sphere. The 日本国語大辞典 gives the example "仁人之所以多寿者、外無貪而内清浄、心平和而不失中正" from the 春秋繁露. (I should note that the word 和平 also exists in Japanese, although it is much rarer and has slightly different connotations from 平和.)

I'm intrigued by the explanation, though; is this a common folk-linguistic belief in China?

leoboiko said,

May 29, 2013 @ 10:42 pm

here are some samples of 平和 in Classical Chinese

Nhan HCMcity said,

May 30, 2013 @ 2:10 am

Vietnamese has the noun+adjective order whereas Chinese has the reverse. So sometimes classical Han is still used, in this case the Chinese order is employed. Funny though after the reunification of the two Vietnam in late 1975, Southerners found it ludicrous about the reverse order in some common compound words like " đảm bảo" , "triển khai" (guarantee, implement); which are mostly found in official propaganda. This recent lunar new year, a friend of mine made a greeting statement using this Tonkinoise reversal style " Mới năm mừng chúc khang an vượng thịnh", which was really farcical.

Victor Mair said,

May 30, 2013 @ 5:44 am

@Nhan HCMcity

Please translate and grammatically explicate "Mới năm mừng chúc khang an vượng thịnh".

When you state that "the Chinese order is employed" in this case, I hope that people don't think you're commenting on the one discussed in this post.

J.W. Brewer said,

May 30, 2013 @ 10:24 am

Wikipedia discussion of the variation among the regional dialects of Vietnamese seems to focus on phonology w/o really addressing differences in syntax. I suppose that by 1975 differences between Hanoi dialect and Saigon dialect could also in part be the result of ideology (I don't know the details of what did or didn't happen in North Vietnam, but certain sorts of self-conscious linguistic innovation/change are reasonably common with revolutionary regimes), but it also seems at least possible in principle that there was pre-existing regional variation in word order preference in this context, with the Northern/Tonkinese stylistic preference obviously becoming more politically/culturally salient nationwide after 1975.

I understand characterizing the perhaps self-concious rejection of Sinitic-style word order in certain fixed phrases etc. as "nationalistic," but I also wonder if that's too simplistic. In any given social/cultural context there are probably multiple potential nationalisms (not all of which may be politically feasible, of course, especially under an undemocratic regime), and an ideology that reappropriates, reemphasizes and reorients the deep Sinitic/Confucian inheritance in Vietnamese culture for its own purposes (whether in language or elsewhere) would be ex ante neither more or less "nationalistic" than one which seeks a rather xenophobic cleansing/purification of the culture (including language) from supposed foreign influence. The situation may be further complicated in the context of Vietnam by the fact that some aspects of the Sinitic/Confucian inheritance (especially in writing systems) were as I understand it squelched by the French colonialists as part of their own agenda, and the Communists were presumably at least as opposed to French colonialism and all its works as they were to some of the Sinitic/Confucian aspects of the ancien regime. I have no idea what the Communists used as a tiebreaker on issues where those two prior regimes had been in conflict with each other.

Bathrobe said,

May 30, 2013 @ 6:09 pm

With Vietnamese, we seem to be venturing into unfamiliar waters, at least for most posters here. Nhan HCMcity was actually referring to the order of elements within words (word building), not the order of elements in sentences (syntax). It is the kind of difference between 和平 and 平和. These kinds of differences are found inside Chinese, too, including between dialects (Mandarin 喜欢 vs Cantonese 欢喜 is one I seem to remember). Whether they relate to differences in syntax is another issue. Before wondering whether đảm bảo, triển khai represent the "reappropriation, reemphasis and reorientation" of "the deep Sinitic/Confucian inheritance in Vietnamese culture", it would be useful to know exactly what phenomenon is being referred to. The linguistic facts, in other words.

My Vietnamese dictionaries give đảm bảo as equivalent to bảo đảm (Sinitically 担保 vs 保担). Both triển khai and khai triển are also listed (Sinitically 展开 and 开展), and seem to be equivalent, except that khai triển has the additional mathematical meaning of 'expansion'.

The sentence that Nhan HCMcity gives includes the words khang an, which has the alternate version an khang (Sinitically 康安 vs 安康) and vượng thịnh, which has the alternate version vượng thịnh (Sinitically 旺盛 vs 盛旺). The variants are found in Vietnamese dictionaries without marking for regionalism or style. Nhan HCMcity is clearly identifying khang an and vượng thịnh as 'Tonkinese', so it appears that the use of one or another is quite salient for Vietnamese speakers. Given that there is still antipathy in the South towards the North, it is interesting that such vocabulary differences have a dimension that is not captured in dictionaries.

Bathrobe said,

May 30, 2013 @ 6:11 pm

Sorry, that should have been: vượng thịnh, which has the alternate version thịnh vượng.

Bathrobe said,

May 30, 2013 @ 6:26 pm

Note also that not all of the examples given by Nhan HCMcity involve 'nativisation'. For instance, Chinese has both 展开 and 开展. It's therefor not necessarily a Vietnamese vs Chinese thing.

JS said,

May 30, 2013 @ 10:23 pm

Check out the Chinese-character rendering of the name of the "Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation" for a similar example… and the website, especially the "Nôm Lookup Tool," is well worth a look as well.

SHD said,

June 4, 2013 @ 12:01 pm

The use of chữ Nôm written from left to right instead of traditional classical way of written Chinese characters as up-down, right to left probably start earlier than post-75, probably occured at the same time when Vietnamese started transcribing tiếng Việt with Latin alphabet. You can see in newspapers published early 19th century or even earlier.

SHD said,

June 5, 2013 @ 11:36 am

Thank you prof Mair for posting about Nôm. I will add a little bit of my knowledge to entertain the readers. In Vietnamese, "nôm na" has a meaning that can be translated as "same same but different". In part of the central and northern region, Vietnamese still call the southern wind that blows northward at the start of every summer season as "Gió Nồm" (lit: wind south) instead of "Gió Nam" (lit: wind south). A Vietnamese scholar looking at "south + mouth" will think of it as "same same but different", and the different or cue is the "mouth" radical telling the reader to read the text with native sound instead of the Vietnamese sounding of the Chinese word also called in Vietnam as chữ Nho. What happen when the reader encounters borrowed Chinese character that has a Nôm reading? Then the context of the sentence and paragraph is used to figure out that the character is supposed to be read as "Nôm" instead as "Nho."

J.Xiao said,

June 6, 2013 @ 7:56 pm

As a native Cantonese speaker, I have little trouble understanding the pái biǎn (Chinese plaque), there are several reasons.

1. Classical Chinese plaques are always read from right to left, just like how one reads Classical Chinese texts. The left-to-right ones are but modern phony replications.

2. Inversion is common in Chinese, like in Classical Chinese and when you compare Cantonese and Putonghua. So it should soon occur to native Chinese speakers that you may need to shift the characters around.

3. I know that the first character stands for Nôm. It's kinda a giveaway.

Eric Vinyl said,

October 24, 2013 @ 7:10 am

I know I’m way late to this party, but I’m adding my 2¢ anyway

There were efforts at creating a Chữ Nôm Wikipedia, but unfortunately, it got canned when the Wikimedia Foundation revised their policy on new projects (chữ nôm doesn’t have its own ISO 639 code). I don’t know if the content that was previously there was preserved or will be moved to a new wiki.

Apparently some 京族 and Việt Hoa still know it, and you can find chữ nôm-subtitled videos/tạp lạp OK on YouTube. There is also a forum and a Facebook page.

Duc said,

November 2, 2013 @ 4:35 pm

As a Vietnamese, I would like to put some of my opinion and hope if I offense anyone, will be forgiven as I don't mean it. The writing was invented by Vietnamese so it's better to look at it in Vietnamese's view. It's under the time where Vietnam just got independence from South China, the language needs to be easy to learn and understand by Vietnamese people but confusing to Chinese people (so their letter can't be read). It's not right for me to say it but Cantonese, Wu , Yue, Min also have a lot of words that can't be written in Chinese (they write in Mandarin format but speak in their own dialect way). Vietnamese used to write in Classical Chinese and spoke in Vietnamese way. For example is the document when the king announced the moving of the capital of Ly Thai To in 1010 from Hoa Lu to Dai La, it was written in totally Chinese with Chinese grammar, not Vietnamese. No modern Vietnam could understand what he wrote (Ancient Vietnamese could I guess). I hope you can see where I am going. So if people use Chinese logic to understand Nom, it's hard to understand Nom.