Aspectual politics

« previous post | next post »

Teenie Matlock, "Framing Political Messages with Grammar and Metaphor", American Scientist Nov.-Dec. 2012:

Millions of dollars are spent on campaign ads and other political messages in an election year, but surprisingly little is known about how language affects voter attitude and influences election outcomes. This article discusses two seemingly subtle but powerful ways that language influences how people think about political candidates and elections. One is grammar. The other is metaphor. […]

The "grammar" part:

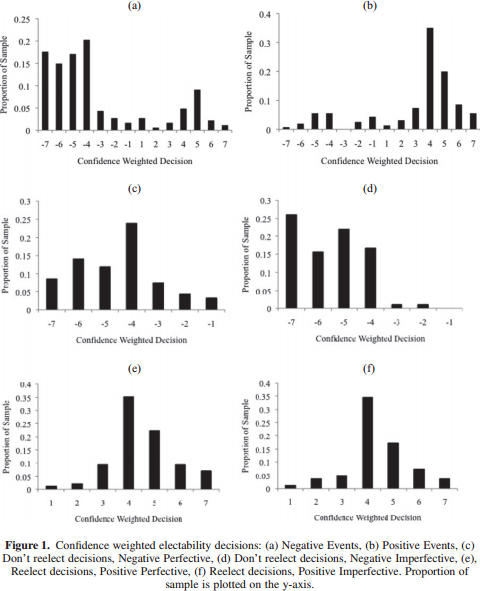

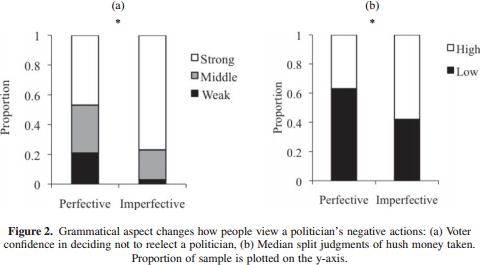

A few years ago, I began exploring the idea of grammatical framing. In an article with Caitlin Fausey, “Can Grammar Win Elections?” published in Political Psychology, we explored the consequences of tweaking grammatical information in political messages. We discovered that altering nothing more than grammatical aspect in a message about a political candidate could affect impressions of that candidate’s past actions, and ultimately influence attitudes about whether he would be re-elected. Participants in our study read a passage about a fictitious politician named Mark Johnson. Mark was a Senator who was seeking reelection. The passage described Mark’s educational background, and reported some things he did while he was in office, including an affair with an assistant and hush money from a prominent constituent. Some participants read a sentence about actions framed with past progressive (was VERB+ing): “Last year, Mark was having an affair with his assistant and was taking money from a prominent constituent.” Others read a sentence about actions framed with simple past (VERB+ed): “Last year, Mark had an affair with his assistant and took money from a prominent constituent.” Everything else was the same. After the participants read the passage about Mark Johnson, they answered questions. In analyzing their responses, we discovered differences. Those who read the phrases “having an affair” and “accepting hush money” were quite confident that the Senator would not be reelected. In contrast, people who read the phrases “had an affair,” and “accepted hush money” were less confident. What’s more, when queried about how much hush money they thought could be involved, those who read about “accepting hush money” gave reliably higher dollar estimates than people who read that Mark “accepted hush money.” From these results, we concluded that information framed with past progressive caused people to reflect more on the action details in a given time period than did information framed with simple past.

The cited paper is Caitlin Fausey and Teenie Matlock, "Can Grammar Win Elections?", Political Psychology 2010, and the effects they found are fairly large ones:

asdf

Here are the alternative wordings used in the experiment:

We just had an election full of attack ads, as well as ads praising candidates' records. Was past progressive aspect more common in the verbal description of negatively-evaluated states and actions compared to positive ones? I don't know any appropriately-organized archive of political advertising in which to investigate such questions. Perhaps a reader can tell us.

A quick look at newspaper stories suggests that there are some patterns to explain — though it's not clear to me what role Fausey and Matlock's idea will play a role in the explanations. In the NYT archives (since 1851), we see

| Obama | Romney | Clinton | Bush | |

| (name count) | 3.64 million | 0.403 million | 1.92 million | 9.84 million |

| was asking | 7 | 18 | 9 | 14 |

| asked | 3,330 | 868 | 1,480 | 2,040 |

| was trying | 2,810 | 98 | 531 | 886 |

| tried | 1,830 | 879 | 1,180 | 1,310 |

| was blaming | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| blamed | 227 | 444 | 81 | 104 |

| was taking | 629 | 116 | 251 | 76 |

| took | 11,200 | 2,750 | 3,130 | 4,660 |

For example, it makes sense that Romney blamed people for things 1.96 times as often as Obama, 5.48 times as often as both Clintons, and 4.27 times as often as all the Bushes, despite being mentioned overall between 5 and 25 times less often. But why was Mr. Obama trying about 1.54 times as often as he tried, whereas the "was trying"/"tried" ratio for the other three names are 0.14 (Romney), 0.45 (Clinton), 0.68 (Bush)?

G Jones said,

November 27, 2012 @ 9:06 am

I'd be curious as to why it makes sense Romney blamed people 1.96x as often as Obama. Because of the NYT's leftwing tilt, or because of your perception of Romney?

[(myl) It makes sense because a major theme of Mr. Romney's recent campaign was the failures of the Obama administration. The first page of hits includes these:

In his latest broadside against the incumbent's foreign policy, Mitt Romney blamed President Obama for the Arab uprisings

Mr. Romney blamed much of the debt problem on Mr. Obama, whom he called an “old school” liberal.

Mr. Romney blamed a “bigger, more burdensome and bloated” government that racked up debt and damaged the nation's credit rating.

On Friday, Mitt Romney blamed President Obama for the April jobs figures,

Mr. Romney blamed his relatively languid campaign schedule — five public events in the past seven days, compared with 11 fund-raisers — on the president’s decision to opt out of the federal campaign finance system four years ago

There are also some blaming events directed at other Republicans and various external influences:

Mr. Romney blamed Mr. Santorum for helping expand the size of the federal government.

Mitt Romney blamed imported tuna. "It's all that immigrant fish," he said.

These ngram-counts are crude measures and might be influenced by random quirks of the indexing and search process, but this particular association does seem to make sense.

]

HaamuMark said,

November 27, 2012 @ 9:22 am

@G Jones: … or because Romney was the challenger and not the incumbent? Whatever the assumption is, it might be free of bias.

GeorgeW said,

November 27, 2012 @ 9:27 am

Do we infer that the past progressive that the action is more likely to be continuing than the simple past?

Mr Punch said,

November 27, 2012 @ 9:47 am

@G Jones – It "makes sense" that the study finds that Romney tends to blame people more than other candidates precisely because we've all noticed that tendency; we've heard him do it in highly publicized (though notionally private, and unguarded) remarks before and after the election.

@GeorgeW – The past progressive implies ongoing, and therefore perhaps repeated action; this could certainly explain the conclusion by those read that version that the candidate had taken more money.

Rod Johnson said,

November 27, 2012 @ 10:02 am

Mr Punch–It doesn't say Romney "tends to blame people." It says Romney tends to use the word "blamed" a lot. I think it highly unlikely that Romney said "I blamed Obama" (or whoever) a distinctively high number of times. However, it seems highly likely that he ascribed that behavior to others–Obama or "liberals" or Democrats "blamed America" or "blamed Bush" or "blamed Republicans" or some such.

It's striking to me that if you express these figures as relative to overall mentions rather than raw token counts, Romney uses "blamed" 17 times as often as Obama.

[(myl) In the NYT index, the bigram "Romney blamed" is never going to be in a quote attributed to him — rather it's someone else characterizing or summarizing Romney's analysis of the causes of some situation or event, as in "Mitt Romney blamed President Obama for the April jobs figures".]

As to trying vs. tried… I would say, for Gricean reasons, tried implies failed. If you had tried and succeeded, you'd say you succeeded; if you had tried and hadn't succeeded (yet), you'd say you are trying.

Ethan said,

November 27, 2012 @ 11:36 am

@Rod Johnson: It doesn't say that either. It says that the word "blamed" was more frequent in NYT stories mentioning Romney than in NYT stories mentioning Obama, Clinton, or Bush. But the "blaming"/"blamed" ratio is near zero across all the NYT stories.

Yuval said,

November 27, 2012 @ 11:44 am

Hmm. Can't the perfective forms just as well be used as passives, making Romney the blamee rather than the blamer? As in, "Romney blamed for strapping the family dog to a space-bound rocket".

J.W. Brewer said,

November 27, 2012 @ 12:01 pm

So the subjects are not even making statements about their own hypothetical voting behavior with respect to the hypothetical candidate but about their own intuitions/expectations about the likely hypothetical voting behavior of their fellow citizens. Why should we think those intuitions/expectations are likely to be accurate? I assume that when you're testing ads for dishwasher detergent or what not you want to know if they make the test subje cts more likely or not to buy your product, not the test subjects' predictions as to how other consumers are likely to respond to your product.

JMM said,

November 27, 2012 @ 12:17 pm

I think the reason it is expected that Romney occurs with 'blamed', is because the vast majority of hits about him are going to come from his recent campaign which was against an incumbent. Blame is something both sides do in that situation I suspect.

(But if you want to feel picked on, go ahead. I support your right to whine.)

Rod Johnson said,

November 27, 2012 @ 2:26 pm

Ethan–fair enough. Uses "blamed" a lot relative to Obama, then. In any event, as everybody has shown, it's not straightforward to go from this fact to any claim about Romney.

Dan Hemmens said,

November 27, 2012 @ 3:14 pm

I think that's probably actually a *better* indicator of effects on voting behaviour than asking people about their *own* voting habits. People are notoriously unwilling to believe that their own behaviours are swayed by this sort of thing, but are quite good at predicting when other people's behaviour will be swayed.

If you judged the effectiveness of adverts by people's willingness to admit to being influenced by advertising, you'd conclude that the whole advertising industry was a gigantic waste of money.

Of course no form of hypothetical question is going to give you reliable data compared to actually observing people's behaviour, but that would be hard to do in a controlled way when you're talking about voting habits.

Ken Brown said,

November 27, 2012 @ 5:54 pm

Isn't this part of what they used to call "rhetoric" when they taught it in schools a couple of thousand years ago?

Dominik Lukes said,

November 27, 2012 @ 6:45 pm

I'm highly suspicious of drawing any conclusions based on this data. It's not that surprising that different aspect of the verb will lead to different framings. As would different tense. The progressive is used for a lot of functions to do with intensification (often negative when used for repeated action). It is likely to be very effective when connected with an action that is profiled by the article.

But there's no guarantee that the same effect would hold for the same verb in a different context.

There's also no guarantee that this has any sort of cumulative or persistent effect.

[(myl) Well, that's why I'd like to take a look at the uses of aspect in political advertising. Their experiments show strong effects that are different (in their interpretation) for positive and negative attributes. But another possibility is that there are many different rhetorical structures that may be involved, and/or many different interactions with the meanings of the verbs involved, with potentially different impacts on impression formation.]

D.O. said,

November 27, 2012 @ 9:16 pm

For a previous take by LL blogger see Julie Sedivy Can grammar win elections?

Nyq Only said,

November 27, 2012 @ 9:41 pm

The claim that only the grammar was changed would seem to be a self-defeating claim. Clearly they altered the meaning of the sentences rather than just the grammar and the resulting effects demonstrates that the meaning was altered. I think that is clearest in the example of 'X was taking money…' and 'X took money…'. The first is suggesting an ongoing situation in which X regularly received money. The second suggest a single event. Of course the one sentence could be substituted for the other but also one would be more appropriate than the other depending on the circumstances. Hence this is more properly described as people inferring different meanings for similar sentences were two different (but related) words were used.

Rod Johnson said,

November 27, 2012 @ 11:28 pm

@Ethan, myl–you're both right, I was being obtuse. Sorry about that.

Joe said,

November 28, 2012 @ 6:25 am

I'd be curious about two aspects of the study. In order for this kind of framing to have effect on election outcomes, we would need to know whether the use of one grammatical form/metaphor over another has a lasting effect, rather than an effect under controlled experiments immediately after being exposed to the stimulus (I'm not sure whether prolonged exposure would have the same effect, for the simple fact that the negative advertising used by both sides might simply cancel one another out). I haven't had time to check a corpus, but I also wonder whether the use of the progressive occurs as frequently as the use of the preterite in the kind of construction used in the prompt. Given the context, I think it would be much more natural to say, "Last year, Mark had an affair with his assistant" than to say "Last year, Mark was having an affair with his assistant" (if there was some reason to use the progressive, say, another event was happening simultaneously, as in, say, Mark was having an affair with his assistant while his wife was working abroad, it wouldn't be so awkward). So while their conclusions might be technically correct (the use of the progressive led people to reflect more on the action), I'm not so sure whether the reason is because of the difference between progressive and non-progressive per se or because the use of the progressive might simply be more usual in that particular grammatical context, which called attention to the action denoted.

(this is one problem with these kinds of studies: if you change the grammatical context, you introduce confounding variables. But if you don't change the grammatical context, you might get a response that registers people sensitivity to the frequency with which forms appear in that context.

Dan Hemmens said,

November 28, 2012 @ 5:48 pm

I'm inclined to agree with Nyq Only that in a lot of cases it seems like changing the grammar actually changes the meaning, which is a bit different to the grammar *itself* having an effect.

DrSAR said,

November 29, 2012 @ 3:05 am

@Dan Hemmens

> If you judged the effectiveness of adverts by people's willingness to

> admit to being influenced by advertising, you'd conclude that the

> whole advertising industry was a gigantic waste of money.

How do we know that's not the case? Given that people doing studies on how well advertising works often have a strong incentive to show that it does, I find it quite possible that in actual fact it does very little (to a large degree).

I am probably being naive, though …

Dan Hemmens said,

November 29, 2012 @ 11:20 am

Actually I suspect that the opposite is true – studies into the effectiveness of advertising aren't usually carried out by ad companies themselves, rather they're carried out by the companies who *commission* the ads, and they have no incentive whatsoever to prove that advertising works (indeed it would be very convenient for them if it *didn't*, because they could slash their massive advertising budgets and spend the money on something else).

Indeed companies often have an incentive to show that their adverts are *less* effective than they really are. The classic example here is cigarette advertising, cigarette companies would love to claim that cigarette advertising doesn't encourage people to smoke, but there is pretty good evidence that it does.

Bathrobe said,

November 29, 2012 @ 11:36 pm

Agree with Joe. Normally you wouldn't find 'Last year he was having an affair with his secretary' in straightforward prose about political candidates. It would be more likely to appear in critical pieces or rants enumerating his infractions: 'Last year he was having an affair with his assistant; this year he's having an affair with his campaign advisor'.

Barbara Phillips Long said,

November 30, 2012 @ 10:06 am

My problem with this study is the selection of participants:

"Participants. A total of 369 undergraduate students at the University of California, Merced, received partial course credit in an introductory cognitive science course or an introductory psychology course. All participants were proficient English speakers in a university community. Fifteen of these individuals provided illegible responses or did not finish the task, leaving 354 participants."

This group — undergraduates — can provide enough data for the researchers to decide whether to go forward with this study. But I am much less interested in these results because the group is not a representative selection of population or of voters.

How difficult would it have been to go out in the community and survey, say, a thousand registered voters by using those undergraduates to help collect the data rather than provide the data?

One of my questions, for instance, is whether the same results would show up in a survey of voters over age 70. This study can't answer this question.

I realize this issue has been raised by others in other cases of research, and that's why I'm aware of it. But now that I am aware, I think the problem is one that researchers need to grapple with.

This research doesn't seem onerous to me. Why couldn't the researchers have found groups of people in the community who were willing to participate in this study? As someone who lived in a college town for 20 years, I can think of many different ways to find people to participate — the participants would still not be representative of the population nationally but would still be more representative because at least their ages would vary.

Maybe the number of science journals could be reduced by limiting all research where participants were college students to a newly instituted "Journal of the Study of United States College Students" and its international counterpart, "International Journal of the Study of Students Pursuing Post-Secondary Education." Research on those outside the academy could be published in any other existing journal.

At least publishing in a putative JSUSCS would signal to us current and former newspaper reporters that the results need to be considered in the context of the participants, not taken as gospel for a trend story about the population as a whole.

Andy Averill said,

December 1, 2012 @ 6:36 am

@Barbara Phillips Long, this is becoming something of a hot topic lately, the number of studies in the social sciences that use college students as subjects, for obvious reasons of economy and convenience. You're right, in many cases they're not a good sample of the population as a whole. Seems to me professional organizations need to have guidelines about when this is or isn't acceptable. Or do they already?

David C said,

December 3, 2012 @ 5:36 am

I'm not familiar with the academic research on this, but I have long suspected that advertising in general has much less impact on election outcomes than politicians assume. I think the 2012 cycle only reinforces this perception. Even with record amounts of advertising spending, the polls barely budged between June and November.

From my wife's past County Commissioner elections, I would guess that advertising may be somewhat more effective in local government campaigns, where there isn't a lot of media attention.

DBP said,

December 11, 2012 @ 3:15 pm

Living in a swing state, the main effect of political advertising in my household was to force us to dvr everything so we could skip past the political ads, which were far more unpleasant than normal advertising. I even started watching football games on at least a one hour delay so that I would not catch up with the live broadcast before the end.

Since the campaigns have ended we have not needed to be as diligent about not watching programs as they are broadcast.