Kim Cattrall's alveolar plosives

« previous post | next post »

Caity Weaver, "Kim Cattrall Can Talk to Me About Anything", NYT 6/6/2018:

Because I’m one of the youngest people alive (29), I was not old enough to be interested in a program with “sex” in the title when “Sex and the City” premiered on HBO in 1998, 20 years ago today.

Consequently, beyond the broadest outlines of the plot — there are four friends, having sex, and the city — the only detail I know firmly about the show is: Sa-MANh-thAH TAL-hkss hLike thIS.

If you have ever seen even one second of the actress Kim Cattrall in character as Samantha Jones, the vamp of “Sex and the City,” you know what I mean. From Ms. Cattrall’s larynx, the words of Samantha slunk and shimmied across the Manhattan of the early aughts, her voice sliding around ribald puns as if extra lubricated. […]

What you might not know is that Kim Cattrall’s real voice is as unlike the voice of Samantha Jones as a late October morning is unlike a Fourth of July high noon. I know this. I know this in my bones. I know this so well the knowing will be imprinted in the DNA of my descendants for a hundred generations — because I am unable to stop listening to the same four podcast episodes featuring Ms. Cattrall, over and over.

They’re very relaxing. […]

When Ms. Cattrall says the word “didn’t,” she respects each and every D and T.

Indeed, it could be said that alveolar plosives — the consonant sounds made by tapping the tip of the tongue to the alveolar ridge, just behind the teeth, as when hitting one’s D’s and T’s — are some of Ms. Cattrall’s best work. She is a careful enunciator who takes time to pronounce distinctly every element of a consonant cluster. Her diction might be described as intricate.

Most native speakers of North American English don’t distinctly pronounce their alveolar plosives (in other words: stops) when they occur at the end of a word. Take, for example, this very sentence, which starts with the word “take” and ends with the word “it.” For many Americans and Canadians, the T of “it” sounds semi-swallowed. Linguists debate whether this muted effect is the result of a failure to release a final, teensy puff of air, or of something happening way down inside the throat, in the space between the vocal cords called the glottis. The point is, the sound is different — smaller sounding — than the T in “take.” Not so for Ms. Cattrall or, as Ms. Cattrall might say, noT so for Ms. Cattrall.

Let me stipulate, as the lawyers say, that Kim Cattrall's voicing of Samantha Jones is indeed different from the voice she displays in recent interviews, and that she has excellent diction in both roles. And it's terrific to see alveolar plosives and phonetic variation discussed in the mass media.

Also, I haven't listened to all of the four podcasts that Ms. Weaver links to. But I was puzzled about the claim that Ms. Cattrall "respects each and every D and T" in didn't. That would be an odd way for any native speaker of North American English to talk, at least if "respect" means "full stop closure and release", as it seems to in this context. And I'd expect listeners to find that pronunciation affected if not downright bizarre, rather than relaxing.

So I downloaded and scanned the first linked podcast — "'Kim Cattrall with Isabelle Huppert' on Talkhouse" — and confirmed my expectation that Kim Cattrall pronounces didn't pretty much like any other careful speaker of North American English. That is, she generally doesn't go all the way to monosyllabic [dɪnʔ] or [dɪn], but she does seriously reduces the /d/ and /t/ in the second syllable. Here's the first couple of examples from that podcast:

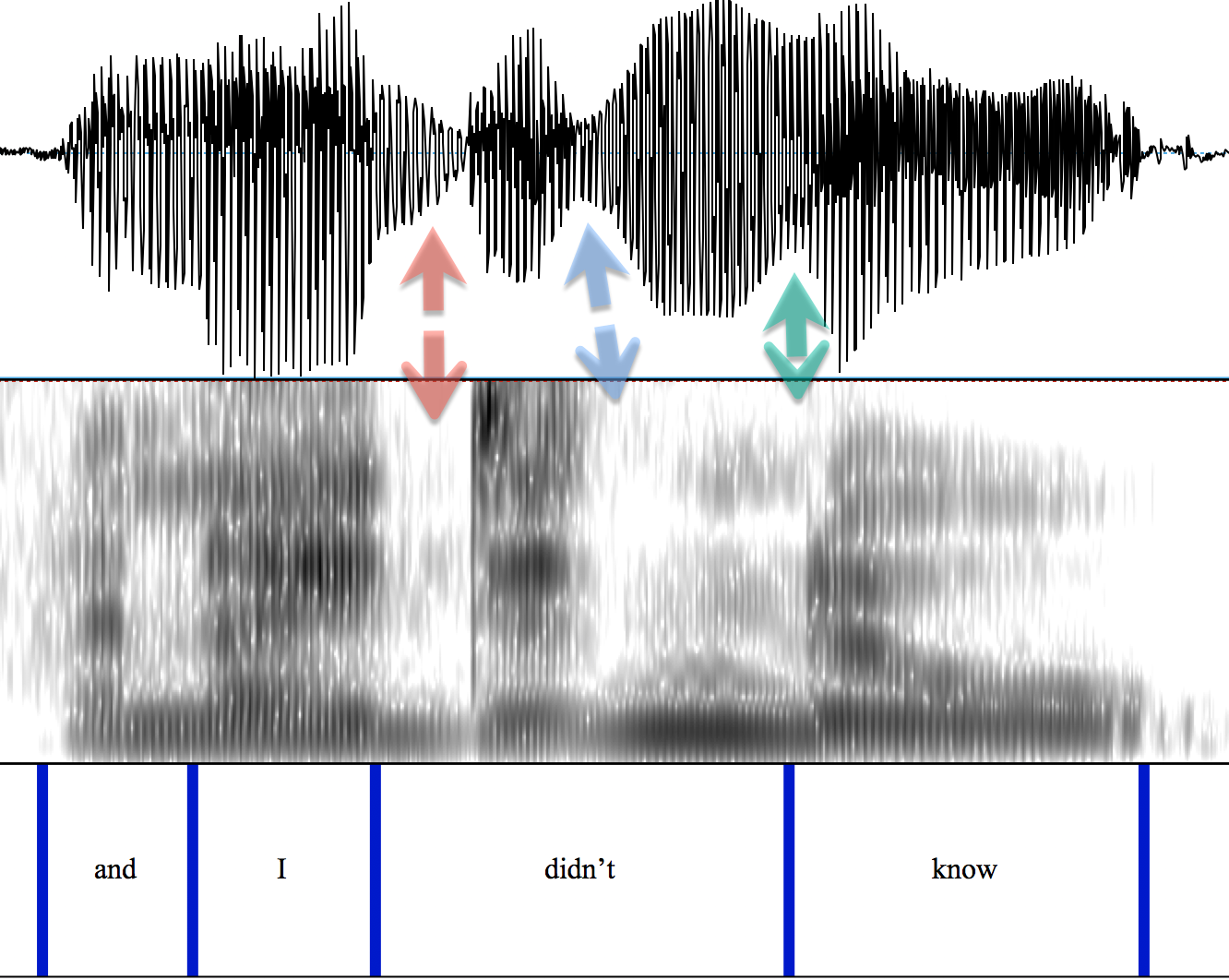

As I observed a few weeks ago in "On beyond the (International Phonetic) Alphabet", we don't have — but also don't need — good ways to characterize such reduction in symbolic terms. Here's her first didn't, with a waveform and spectrogram in which pronunciation of the word-initial /d/ is marked with a red arrow, the word-medial /d/ with a blue arrow, and the word-final /t/ (if it exists at all) with a green arrow:

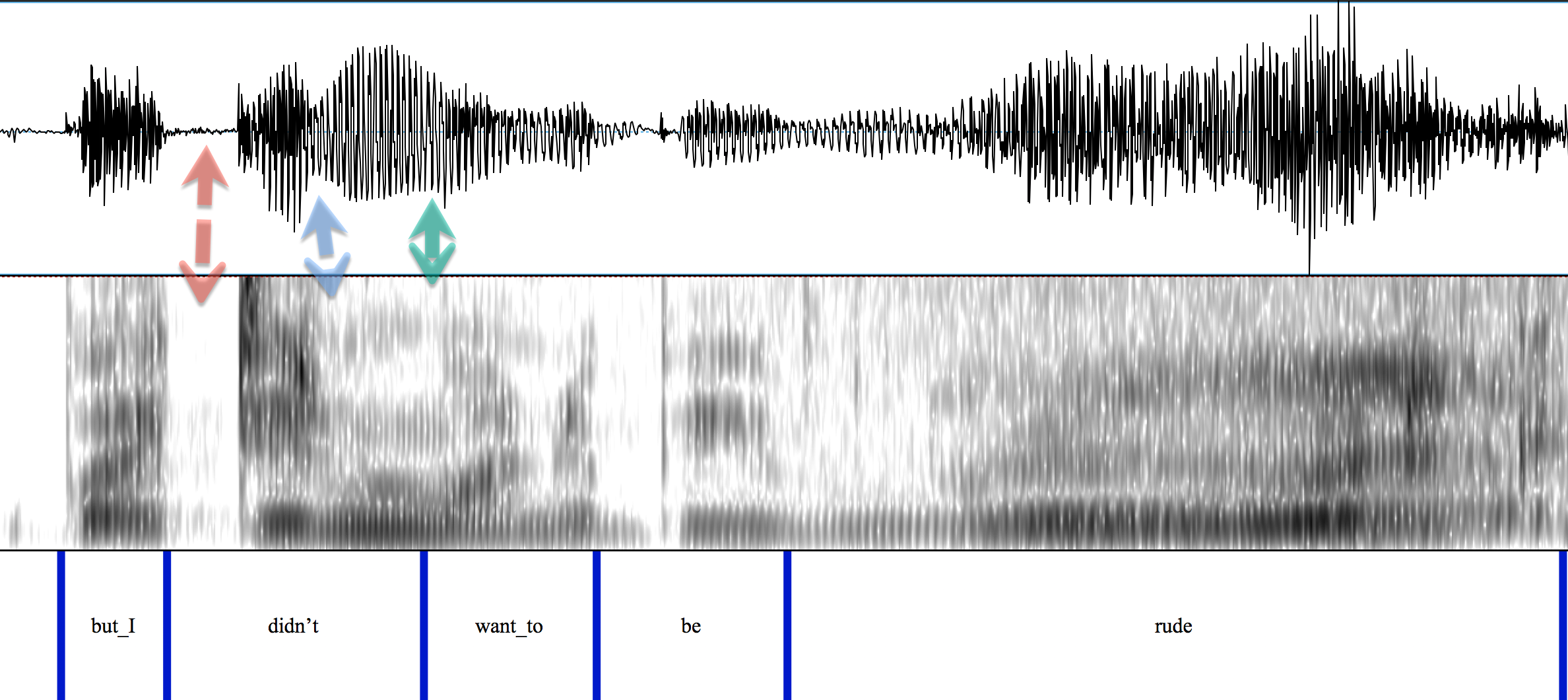

Here's the same treatment for her second didn't from that clip:

Note also that "want to" becomes [wɐɾ̃ə], with a medial nasal flap and no residue of the two t's — what's commonly written "wanna" — just as we would expect for any speaker of most varieties of North American English.

And at the start of her second phrase, I believe that she's managed to reduce the but in "but I" to a voice labiodental onset, which again is a normal thing.

I could go on to present the first few unreleased word-final /t/ and /d/ sounds in that same interview, but you get the idea. As I said, I'm really happy to see phonetic terminology and discussion of phonetic variation in the popular press, and I'm sure that there's something about Kim Cattrall's speech that Caity Weaver is responding to. But if the attraction is what she describes, it must be happening in parts of the podcasts that I haven't heard yet.

Andrej Bjelaković said,

June 7, 2018 @ 9:10 am

And how would you characterize Samantha's speech? What would the main differences be, compared to RL Kim's speech.

Jonathan said,

June 7, 2018 @ 11:05 am

I don't know about her "didn't", but that's one heck of a Canadian "know".

BZ said,

June 7, 2018 @ 12:27 pm

Having never watched "Sex and the City", I have no idea what "Sa-MANh-thAH TAL-hkss hLike thIS" means. If the all capitals are meant to denote stress, it seems pretty much like a normal stress pattern except maybe the "thAH". Does that denote lack of reduction of the final vowel? And what about the the intrusive "h"s between consonants? There is certainly no way those are literally "h" sounds. Are they supposed to indicate pauses between syllables and words?

ngage92 said,

June 7, 2018 @ 12:43 pm

This reminds me that Christina Aguilera did a spot-on impression of Samantha in this SNL sketch from around the time the show ended: http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xkun1a

KevinM said,

June 7, 2018 @ 12:53 pm

Some bio may be relevant. According to imdb she was born in England, to (presumably) English parents, who raised her in Canada, and she return to England at 11 for dramatic training:

Kim Victoria Cattrall was born on August 21, 1956 in Mossley Hill, Liverpool, England to Gladys Shane (Baugh), a secretary, and Dennis Cattrall, a construction engineer. At the age of three months, her family immigrated to Canada, where a large number of her films have been made. At age 11, she returned to her native country and studied at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art. She returned to Vancouver and, at age 16, graduated from high school and won a scholarship to study at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York City.

Chandra said,

June 7, 2018 @ 3:05 pm

@Jonathan – I know about Canadian "about"s and "sorry"s and "nice"s, but I've never heard of a Canadian "know". FWIW as a Canadian, her pronunciation of "know" sounds a bit odd to me, maybe influenced by her English parentage?

David Marjanović said,

June 7, 2018 @ 5:14 pm

I can't hear that. Instead, the I is missing: I hear a loud and clear but didn't, starting with unreduced [b̥ʌd̥ː].

Nope, that's anti-English. Some Canadians use [e] and [o] for the FACE and GOAT vowels, just like the Scots do. In England, GOAT is a diphthong that keeps fronting, having reached [œy̑] for some, and FACE is a diphthong that has opened to [ai̯] for some.

JPL said,

June 7, 2018 @ 10:38 pm

@David Marjanovic

I've long noticed with curiosity that GOAT vowel as you describe it (front rounded and raising) in some English speakers; is it associated with some region or regional dialect or other? I think the same thing may be going on in North Carolina. Is there some connection?

J.W. Brewer said,

June 8, 2018 @ 6:44 am

JPL: Quoth the internet: "Another prominent differentiating feature in regional North American English is fronting of the /oʊ/ in words like goat, home, and toe and /u/ in words like goose, two, and glue. This fronting characterizes Midland, Mid-Atlantic, and Southern U.S. accents; these accents also front and raise the /aʊ/ vowel (of words like house, now, and loud), making yowl sound something like yeah-wool or even yale." I associate it personally with the MIddle-Atlantic varieties (i.e. those spoken in the environs of Philadelphia and Baltimore) because that is my own regional background and GOAT-fronting and GOOSE-fronting are among the most notably regional/non-standard pronunciation features of my idiolect (my youngest child – age 3 – is already aware that there are certain words in these categories that Dada pronounces one way while Mama and his big sisters pronounce them another way), but that doesn't mean it isn't also present in e.g. a North Carolina accent where there would be to my ear enough other phonological "tells" of regionality that I don't focus on that one.

Rodger C said,

June 8, 2018 @ 8:31 am

GOAT with [œy̑] was already in use among affected high-school girls in West Virginia in the 1960s.

J.W. Brewer said,

June 8, 2018 @ 9:34 am

Yeah Ms. Cattrall's GOAT vowel is the opposite of the fronted one I have. In a US-regional-dialect context it's the one stereotypically found in Canada-adjacent locations like Minnesota and its neighboring states.

mollymooly said,

June 9, 2018 @ 9:03 am

A thing that strikes me as American is non-syllabic 'd after word-final d or t, e.g. "What'd you say?" or "It'd be nice."

David Marjanović said,

June 9, 2018 @ 3:36 pm

I'm sure the variation in how far fronted it is (merely partially centralized pronunciations like [ɵʊ̯] seem to be more common than the fully front extreme) is geographic, but I know very little about the dialect geography of England.

Various extents of fronting are very widespread in the GOOSE vowel, in England and elsewhere; but there, too, I happen to know next to nothing about the geographic distribution.