Special diligence: police and security forces in China

« previous post | next post »

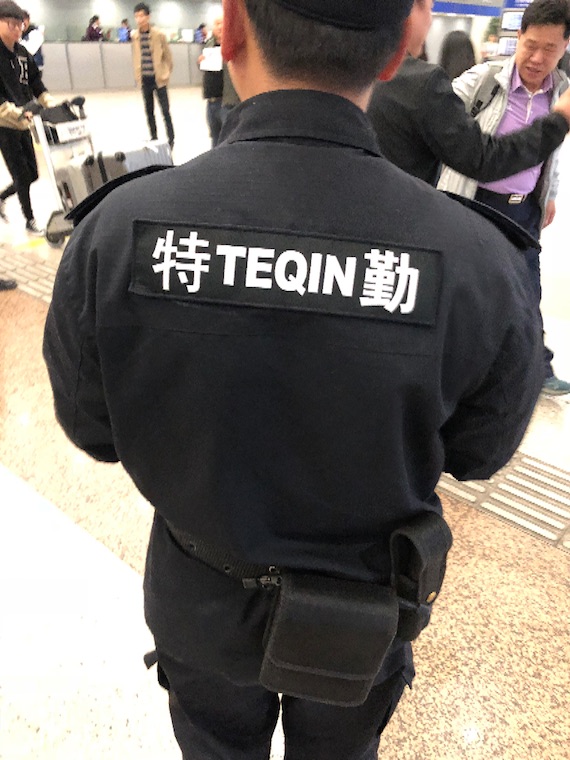

Paul Midler came upon this scene in the Shanghai Pudong Airport:

You can tell from their look, from the items hanging from their belt, and from the fact they're frisking passengers that the fellows in black belong to some sort of security force, but exactly who they are and who they work for is a bit of a mystery. One thing, though, is certain: these men in black are increasingly prevalent in China nowadays.

The bold characters and Pinyin on the back of the man in the center of the photograph say "tèqín 特勤". There's no fixed translation for that term yet, so for the moment I'll just translate it literally, syllable by syllable, as "special diligence". Perhaps, by the time this post is concluded, we'll have a better idea of what "tèqín 特勤" signifies, who deploys these guards, what their duties are, and so forth.

Paul, who is an old China hand and knows Mandarin well, asked one of the men what "tèqín 特勤" means, and the guy replied, "I don’t even know". More precisely, the exchange went something like this:

"Tèqín" shì shénme yìsi?

Wǒ yě bù zhīdào!

特勤是什么意思?

我也不知道!

What's the meaning of "tèqín"?

I don't know either.

(Upon reading this, one correspondent from China remarked: "This teqin seemed very pessimistic about his own job…".)

So even the guy who is a "tèqín 特勤" doesn't know what "tèqín 特勤" means for sure.

Paul followed up by asking another one of the tèqín 特勤 how the tèqín 特勤 differ from the infamous chéngguǎn 城管 ("urban management") parapolice who are ubiquitous in Chinese cities and who cause so much friction (and sometimes even death) with peddlers and other folk who frequent China's streets and alleys.

See: "More anti-Japanese slogans, but with a twist" (9/21/12)

The tèqín 特勤 told Paul, "we are for indoors". More about that anon.

Before proceeding, I want to mention that it is not at all unusual to use any of the following on the uniforms, vehicles, and equipment of police and security forces in China: characters alone, characters plus Pinyin, characters plus English, Pinyin alone, English alone.

See, for example:

"Pinyin in practice" (10/13/11)

Here are photographs (all from Paul) documenting a few of these varieties of identifying police and security forces:

This photo is from two years ago. It's probably what they wore before they became tèqín 特勤.

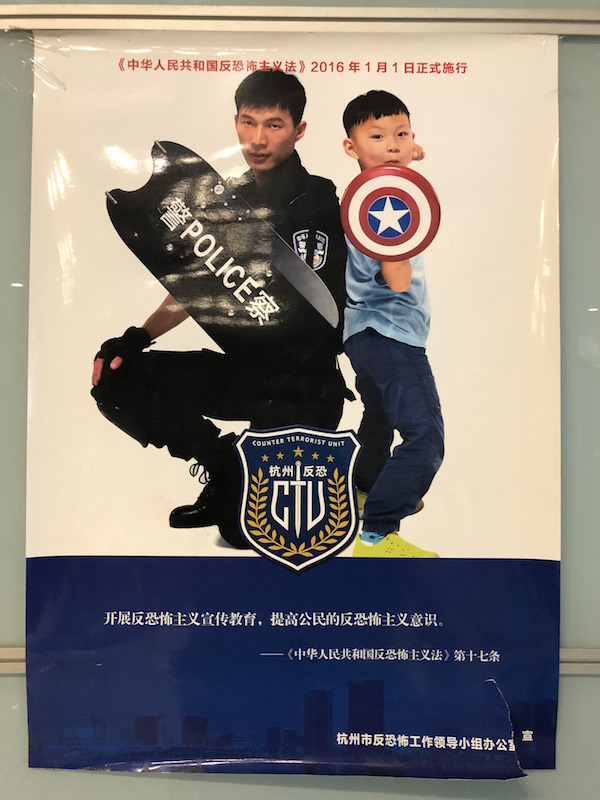

Notice the Chinese character [jǐng]chá [警]察 ("police") on the left side of the helmet.

Notice the Captain America shield!

What I'm trying to figure out now is which branch of the police apparatus the tèqín 特勤 are attached to, or whether they can be part of various police forces.

One of the questions I started out asking is whether they are affiliated with the chéngguǎn 城管 ("urban management") parapolice, and it is clear that they are separate. But there is much about them that is still very murky.

One correspondent wrote back:

Yes they are most certainly separate [from chéngguǎn 城管 ("urban management")], and are not affiliated with any specific kind of organization. They are kind of like hired muscle [VHM: I love the way he put that]. Sometimes the police hire teqin to do things too boring or simple for normal police to do. More often, though, organizations hire them for help, like schools when they have events or need extra ménwèi 门卫 ("guards").

They are not police and are not chengguan.

My reply to that:

They almost sound as though they are a private company or companies for hire. I guess they don't belong to any particular part of government. But then I wonder who owns / organizes /controls them, and who makes money off them? And how are they recruited / hired?

My correspondent continued:

There are "teqin" everywhere. They are kind of somewhere between bǎo'ān 保安 ("security guards") and police, but they have very specific roles. I have seen them directing traffic for events and managing the rush-hour crush in subway stations. They are ubiquitous, and usually pretty useless if you actually need help with something. I actually took the subway today in Xi'an and one was standing next to me.

From another correspondent (with some Pinyin and translations added by VHM):

I always thought that Te Qin are a part of the military but I never thought about it thoroughly.

Baidupedia says Te Qin 特勤 is a short term for tèshū qínwù 特殊勤务 ("special service / duty"). There are two types of tèqín 特勤: gōng'ān tèqín 公安特勤 ("Public Security Special Service") and ānbǎo tèqín 安保特勤 ("Security Special Service").

The Baidu article goes on to say that we may render "tèqín 特勤" as SWAT, but I think that is dead wrong for at least two reasons:

1. SWAT (Special Weapons and Tactics) teams are heavily armed, whereas "tèqín 特勤" are barely armed at all.

2. The Chinese name for "SWAT" is tèjǐng 特警, which is short for tèzhǒng jǐngchá 特种警察 (lit., "special police"), whereas "tèqín 特勤" is short for tèshū qínwù 特殊勤务 ("special service").

An earlier post on Chinese SWAT teams:

"'Suffered We Protect They'" (12/22/14)

Finally, observations from yet another correspondent on the plethora of police and security forces that swarm throughout the PRC (with some Pinyin and translations added by VHM):

Gōng'ān tèqín 公安特勤 ("Public Security Special Service") is surely a part of the gōng'ān 公安 ("Public Security") system while ānbǎo tèqín 安保特勤 ("Security Special Service") sometimes could be people from security companies (ānbǎo gōngsī 安保公司). These tèqín 特勤 usually are in charge of special tasks (tèshū qínwù 特殊勤务) such as anti-terrorism patrol (fǎnkǒng rènwù 反恐任务). I always see these people in Te Qin uniform at subway stations in China. Now everyone who rides the subway is required to have their bags checked by the machine to ensure safety.

Chéngguǎn 城管 ("Urban Management") are very different. They are in charge of the city management, such as public transportation, environmental issues, maintenance of the cityscape, etc. They are often seen on streets asking street vendors to leave. Sometimes I also see them on the news when some factories violate environmental laws.

I think tèqín 特勤 are not only for indoors. These years, China has created many new names for law enforcement agencies. So we have wǔjǐng 武警 ("armed / military police"), jiāojǐng 交警 (traffic police), jǐngchá 警察 ("police"), tèjǐng 特警 ("special police"), xiéjǐng 协警 ("auxiliary police"), chéngguǎn 城管 ("city management"), xiéguǎn 协管 ("assistance"), bǎo'ān 保安 ("security"), tèqín 特勤 ("special service"), tèbǎo 特保 ("special security") and so on.

In fact, only jǐngchá 警察 ("police") and chéngguǎn 城管 ("urban / city management") have legal enforcement power and other titles do not have legal enforcement power. Wǔjǐng 武警 ("armed / military police") belong to the army and tèjǐng 特警 ("special police") work on particular cases, especially some dangerous cases. As for why we have so many titles, I believe that originally the government needed a group of people to work for them but did not want them to seem to represent the government. For example, policemen are officials, and once they use violence and cause injuries to people, society would condemn the government; but if the government uses non-official groups such as xiéjǐng 协警 ("auxiliary police"), then they can claim that the government is not involved in violence when people condemn them. I think it is a kind of strategy because the government or the official policemen do not stop xiéjǐng 协警 ("auxiliary police") when these xiéjǐng 协警 ("auxiliary police") exercise law enforcement power, even though they clearly know that xiéjǐng 协警 ("auxiliary police") do not have any law enforcement power. There is thus a convenient vagueness concerning the wielding of police power by xiéjǐng 协警 ("auxiliary police") who technically do not have it.

Later, people also found that they could take advantage of this vagueness and exploit it, so more and more tèqín 特勤 ("special service") personnel appear. At first, tèqín 特勤 ("special service") and tèjǐng 特警 ("special police") belonged to the same camp. Gradually, however, the definition of tèqín 特勤 ("special service") is becoming vaguer and vaguer, and more and more organizations hire people as tèqín 特勤 ("special service"). Considering reports of the social conflicts that have resulted, the government and police security bureau insisted many times that the system does not have tèqín 特勤 ("special service") as part of their organization, and people who wear clothes with tèqín 特勤 ("special service") written on them are not official. In fact, the clothes with tèqín 特勤 ("special service") are common and anyone can buy them online, and people may feel that when they wear this kind of clothing, it is easy for them to exercise power or even apply violence.

But in Guangzhou Metro, people who are in charge of security check also wear tèqín 特勤 ("special service") clothes. There is no doubt that Metro belongs to the government, so I still think that tèqín 特勤 ("special service") is a kind of official group, but — at the same time — everyone could become a 特勤 because its definition is unclear.

One thing we may say for sure is that the tèqín 特勤 who are the subject of this post are completely different from the tèqín 特勤 of historical records dating back more than a thousand years. The latter, a Turkic title, Tegin (also tigin, tiğin), is commonly attached to the names of junior members of the Khan family. No matter who exactly today's tèqín 特勤 are, no matter who they work for or who deploys them, they are an essential component of the veritable blizzard of police and security forces that blanket the PRC.

[Thanks to Brendan O'Kane, Francis Miller, Jinyi Cai, Zeyao Wu, Fangyi Cheng, Yixue Yang, Geoff Wade, and Jichang Lulu]

Victor Mair said,

April 14, 2018 @ 12:43 pm

From Marcel Erdal:

Turkish (and before that Ottoman Turkish) also has an adjective tekin which can roughly be translated as 'free from evil forces' (mostly said of places). That presumably helped with the 'k'.

Victor Mair said,

April 14, 2018 @ 12:44 pm

From Mehmet Olmez:

Old Turkic script system (Turkic runes) differs k and g (both: velar and front!). ** tegin written always with ** g in Old Turkic inscriptions. Mostly it was written like following: tgin. Maybe, it must be interpreted as tägin. But when we check Old Uighur texts, it was written as tykyn (= tigin, better to read tegin). Because in Old Turkic runic system (inscriptions from Mongolia) there is not distinction between e and ä. But Yenisei Inscriptions have both, ä and e. There is also i at both group (Yenisei and Mongolia).

[**VHM: I regret that the Old Turkic runes wouldn't reproduce here. For anyone who really wants to see them, I'll send them via e-mail.]

Shortly: If any word written with i, and ä at Orkhon Inscriptions, we can interpret it as closed e; or if any word written just with (ä) (without vocalization) at Inscriptions and with y (i) at Uighur texts, we should accept it with closed e.

Examples from runic:

bir- / br-, biš / bš, il/l, it-/t- ;

From Uighur script:

bir- , biš , il, it- (should be read: ber- , beš , el, et- ) ;

For e/ä/i please look at chapter at § 7.2

https://www.academia.edu/18375569/What_Should_a_New_Edition_of_the_Old_Turkic_Inscriptions_Look_Like

Victor Mair said,

April 14, 2018 @ 2:03 pm

From Peter Golden:

Yes it is. It is based on the Arabic-script rendering of the title تكين (takīn) – Arabic had a “g” but it became “j”. It remains “g” only in Egyptian Arabic. ك is regularly used to render “g,” but in Persian and Osm. Turkish, among others, the letter گ was created to render “g”.

VHM: My question was whether this old title — Tegin, etc. — is the source of the modern Turkish name "Tekin" (e.g., my old friend, Şinasi Tekin).

Victor Mair said,

April 14, 2018 @ 2:37 pm

From Peter Golden:

Marcel makes a good point. Tekin does mean “auspicious” etc. The two could reinforce each other. But, so many people, esp. scholars, took surnames that echoed the Turkic past. I have in mind the scholar E. Şapolyo whose name is the Turkish rendition at that time of the Chinese rendition (沙鉢略) of the Old Türk title ışbara which came to Turkic from Sanskrit îśvara probably via Sogdian or even Tocharian. I guess one would have to ask the families in question what they had in mind when choosing a last name.

In the US, as is well-known to Americans, last names were often decided by the scribes at Ellis Island or other official points of entry. Sometimes schools played a role too (my last name was the result of what the (most probably Irish) registrar decided was “right” when my father enrolled in school. Golden is a fine Irish name. Indeed, there is a Peter Golden who was a specialist on Irish folklore and wrote a book well known in the Irish community: “The Voice of Ireland”). Erin go Bragh!

Victor Mair said,

April 14, 2018 @ 3:08 pm

From Peter Golden:

I periodically get emails from folks in County Cork or Mayo, wanting to know if we are related. My usual response is: “if they reached Ireland via Belarus’…there may be a chance” :)

Jeremy Daum said,

April 14, 2018 @ 8:33 pm

Fairly certain that Teqin are just security guards and that the confusion comes from the similarity of their uniforms to those of real police and local governments use of them to carry out semi-law enforcement functions.

See https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1717612; http://www.suzhouteqin.com/

Victor Mair said,

April 15, 2018 @ 10:47 pm

From Francis Miller:

Some other interesting thing I heard recently when I discussed teqin with a Chinese friend was: apparently most companies practice hiring discrimination based on appearance of the men they recruit to fill teqin roles, because the government bureaus and companies who hire them want more "friendly faces", and pay more for more "handsome looks". I have not found the weibo post that purportedly exists to substantiate this claim. Although I'm definitely not a contract security expert, I would guess this is common practice elsewhere such as in the U.S.

Victor Mair said,

April 15, 2018 @ 10:50 pm

I'm certain that looks and height are criteria for hiring into certain divisions of the foreign affairs bureau of Sichuan Province. People who work in them told me as much.