Yellow, gambling, poison

« previous post | next post »

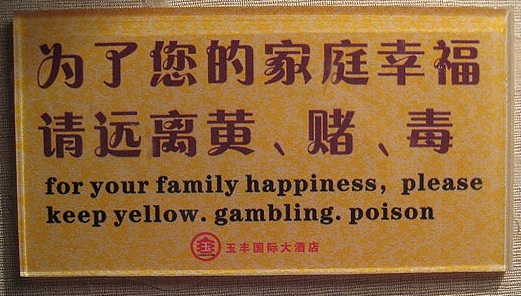

Laura Bailey sent in this Chinglish specimen from Jingzhou, China which was spotted by John Hotchkiss and published as sign of the week no. 181 in the travel section of the Telegraph:

The Chinese wording reads:

Wèile nín de jiātíng xìngfú

为了您的家庭幸福

qǐng yuǎn lí huáng, dǔ, dú

请远离黄,赌,毒

Beneath the Chinese is the following English translation: "for your family happiness, please keep yellow, gambling, poison."

Anyone reading this English translation will be completely dumbfounded and have no clue whatsoever about what they are expected to do for their family happiness. Even if they are curious enough to consult the most popular online translation services, they will still be left in the dark.

Google Translate: For your well-being of your family away from pornography

Baidu Fanyi: For the happiness of your family from vice

Babel Fish: For your family happy please be far away from Huang Dudu

What the Chinese really means is this: "For your family's happiness, stay far away from prostitution, gambling, and drugs."

The first clause is easy, both for machines and for humans. But the second clause shouldn't be that difficult either.

qǐng 请 ("please")

yuǎnlí 远离 (["stay / keep] far away from")

It is the next three characters that seem to throw everything and everyone for a loop. Perhaps it is the inserted commas that disturb the interpretive processes. After all, the expression "huángdǔdú" 黄赌毒 garners a phenomenal 3,630,000 ghits.

So what does it mean?

In a sense, we may say that "huángdǔdú" 黄赌毒 is a sort of acronym standing for:

1. huángsè 黄色, lit. "yellow color," but also meaning "pornography" and, by extension, "prostitution"

2. dǔbó 赌博 ("gambling")

3. dúpǐn 毒品 ("drugs, narcotics" and, by extension, "drug trafficking")

Hence, "huángdǔdú" 黄赌毒 refers to the sorts of things that vice squads go after, and if you look up 黄赌毒 on Google (especially Google images), you will read reports and see images of raids on dens of iniquity where police are hovering over and rounding up individuals who are engaged in such activities.

Cantonese has an extended quadrisyllabic, acronymic expression that boils down to the same thing ("vice"):

wong4 dou2 duk6 hak1 黃賭毒黑 ("prostitution and pornography, gambling, narcotics, and organized crime")

wong4 黃 = all businesses and materials of a sexual nature (such as "yellow" films, novels, magazines, prostitution, etc.)

dou2 賭 = gambling

duk6 毒 = drugs

hak1 黑 = organized crime (from hak1 se5 wui2 黑社會 [lit., "black society"])

The failure to convey the meaning of "huángdǔdú" 黄赌毒 stems from the breaking up of what is essentially an acronym into its constituent components without restoring them to their full forms.

Finally, the only context we have for the sign is that it is either in or sponsored by a hotel (as evidenced by the fine red print at the bottom). So what does a sign like this have to do with a hotel? Well, those of you who have stayed in less reputable Chinese hotels know what it is like to receive those dreaded phone calls in the middle of the night, in which a woman asks if you're lonely and need anything from her. And, if you are concerned about the well-being of your family, you had better be careful when you go to their barber shops and massage parlors.

Dave M said,

December 8, 2011 @ 10:12 pm

Interesting that they think that smut is "yellow" while we call it "blue". (I think it's "pink" in Japanese, which I suppose makes a bit more sense.)

Eric TF Bat said,

December 8, 2011 @ 11:05 pm

Dave M: assuming some ideas about skin colour that I thought were stereotypically western, it's only "blue" that doesn't make immediate sense…

Tom S. Fox said,

December 8, 2011 @ 11:09 pm

Very yellow, very violent.

Ray Girvan said,

December 8, 2011 @ 11:13 pm

> huángdǔdú

That expression irresistibly brings to mind "wangdoodle".

DW said,

December 8, 2011 @ 11:31 pm

Input as in the sign —

为了您的家庭幸福

请远离黄,赌,毒

— Google Translate gives me:

For your family happiness

Please stay away from pornography, gambling, drugs,

… not too bad, I guess. Of course changing spacing or punctuation changes my result.

Matthew Stuckwisch said,

December 9, 2011 @ 3:36 am

Dave M: and in Spanish, green is traditionally the colored associated with it (un hombre verde — a dirty ol' [smut-dirty, not homeless dirty] man).

Nicki said,

December 9, 2011 @ 4:21 am

Nice one! I especially enjoyed it, having recently added 毒 to my Chinese studies in the wake of the poisonous Coca-cola drink product scandal. This post was the perfect reinforcement to my study. I've just put up a post at my blog discussing this LL post and the relationship of 毒 and 药 to the English word poison, feel free to post corrections, rebuttals and or general derision there!

Antariksh Bothale said,

December 9, 2011 @ 5:10 am

Is there a name for this ribbon style writing style? It looks pretty cute!

RW said,

December 9, 2011 @ 5:24 am

So the colour of sleaze is yellow in China, pink in Japan and blue in English-speaking countries. It's green in Spanish. Why should a particular colour end up having sleazy connotations, and why should it end up being such different colours in different languages? Curious.

Theodore said,

December 9, 2011 @ 7:51 am

@Ray Girvan: Thanks for the image of Howlin' Wolf belting out "We gonna pitch a Huang dang dudu all night long".

Beth said,

December 9, 2011 @ 8:52 am

My understanding is that in English speaking countries "blue" refers to morality (blue-stockings, blue-laws) and the "blue" description means that it would be banned for moral reasons.

Red (red light district), on the other hand, would refer to vice.

Faldone said,

December 9, 2011 @ 9:33 am

And how did the commas get translated as periods?

Rodger C said,

December 9, 2011 @ 12:36 pm

@Beth: But in my day, at least, there were "blue movies," which in Spanish were "películas verdes."

William Ockham said,

December 9, 2011 @ 12:46 pm

I would think that a similar problem might happen in reverse if an American English sign said "For your family's happiness, stay far away from the red light district."

Jerry Friedman said,

December 9, 2011 @ 1:13 pm

I assumed Spanish verde was from viejo verde, a dirty old man, green in the sense of not withered. Is that right?

Jason Cullen said,

December 9, 2011 @ 4:51 pm

Two comments.

First, to Faldone, modern Mandarin employs two kinds of comma: one for separating clauses and phrases (identical two our comma, {,}) and another introducing serial phrases, and which looks like a right-ward, downward pointing straight line, {、}. The author was probably confused to only find one mark available and settled for a period being closer to a comma; I don't find this surprising as most Chinese in writing English represent commas as a quick dot, not unlike a period.

Second, I will never forget a night spent in a hotel in Changchun (Jilin Province). At 8:00PM I got a phone call from a young woman calling to ask if I were cold and needed a blanket. "No, thank you." Then at 10PM I got an identical call from yet another woman. "No, bye." Finally, at 10:30PM I got a call from a young man asking the same question. Well, an A for catering to everyone's needs, but an F for not taking a hint; I hung up and disconnected the phone!

James Iry said,

December 9, 2011 @ 5:14 pm

How would you respond if you did in fact need a blanket (and nothing more)?

Victor Mair said,

December 9, 2011 @ 9:59 pm

@James Iry

In a place like Changchun (northeast China), there are usually plenty of blankets on the bed and extras in the closets.

Terry Collmann said,

December 10, 2011 @ 12:42 am

The translation widget on my iMac has for the last part of the phrase "Please be far away yellow, gambling, poisonous" if you keep the commas in, but "Please be far away from Huang Dudu" if you take the commas out (even if you leave the spaces in), so the commas are certainly not helping.

Janice Byer said,

December 10, 2011 @ 1:04 am

Rodger, I likewise remember when porn flicks were "blue movies" after which they were "XXX-rated" and then "adult" – the "blue" from the laws then restricting their distribution.

Ray Girvan said,

December 10, 2011 @ 7:04 am

@ Victor Mair: 黄赌毒 is a sort of acronym …

Or perhaps a portmanteau word, like coing a word "sedruro" for "sex, drugs, rock & roll".

nbm said,

December 10, 2011 @ 1:45 pm

RW: I saw what you did there.

There must be literature on the derivation of "blue laws," which regulated not only sexual but other moral matters. It was not so long ago that the (blue) laws in New York City, famous haunt of vice, were changed to permit the sale of liquor on Sundays, for example. I'd assume this blue was related to the bad-language blue of the comedian ("working blue") or the sailor ("the air blue with expletives") but not to the blue of blue-stocking. A bluestocking was an educated or intellectual woman; I am sure there are those who found this a morally uncertain status, but it doesn't mean bluestockings talked dirty and I don't get the sense that it indicated sexual looseness.

But someone probably knows the facts of the matter, beyond my guesses.

Tim said,

December 10, 2011 @ 3:52 pm

Well, here's what I can glean from some quick research, using the OED and the Wikipedia.

The OED gives the original meaning of blue-stocking as "Wearing blue worsted (instead of black silk) stockings; hence, not in full dress, in homely dress. (contemptuous.)" Apparently, the term was used to refer to Cromwell's supporters, due to their "puritanically plain or mean attire". From there, we get an association of blue with strict morality, which leads to blue laws. Presumably, once the origin of that phrase was forgotten, the association of blue was transferred to the things the blue laws were set up to oppose, rather than the ideas they were meant to uphold.

So, ultimately, blue = immoral because some sixteenth-century prigs wore cheap socks.

Tim said,

December 10, 2011 @ 3:54 pm

Crap. Seventeenth-century prigs. I really should check these things before hitting "submit".

Victor Mair said,

December 10, 2011 @ 5:45 pm

I regularly receive a book and gift catalog from an outfit that calls itself "bas bleu". At the bottom of the online home page (http://www.basbleu.com/), there is the following explanation of their name:

bas bleu (bä blũ) [Fr., blue stocking, bas, stocking, bleu, blue.] A literary woman; a bluestocking

(it took me nearly an hour to put that tilde over the "u", and I don't even know why it's there — perhaps simply to look phonologically exotic?)

When it comes to French fashionistas and Cromwellian puritans, are their conceptions of blue stockings so different as this?

Janice Byer said,

December 10, 2011 @ 9:16 pm

Professor Mair, my guess is the American meaning stems from our having had, in colonial times, a Puritan theocracy so notorious for its repressive laws it sustains horrific myths. The avant garde French are reportedly informed instead by a benign 19th century women's literary society.

Tim said,

December 11, 2011 @ 1:44 pm

The OED's etymology for blue-stocking :

So, it seems that certain seventeenth-century Puritans and certain eighteenth-century intellectuals had similar fashion senses.