Caesar and the power of No

« previous post | next post »

I sometimes make my way to the multiplex to see and report to you on important films that bear on language-related matters. (Sometimes unsuccessfully. You may recall my glowing account of The Oxford Murders back in 2008. I do hope the director hasn't got out of hell yet.) Back in June I tried to report to you on a special advance showing of a documentary about a chimpanzee sign-language training experiment, Project Nim, but couldn't get in. I had forgotten to allow for the fact that it was part of the Edinburgh Film Festival and (typical of the intellectual enthusiasm of this city) the place was thronged. Not a ticket to be had for love or money. (I will try to catch Project Nim soon; it is on wider release in the UK as from today.) But last night I had a significant success in that I managed to actually get in through the doors (vital prerequisite for really informed movie review) for a screening of one of the most important recent films on primatology research.

Yes, I went to see Rise of the Planet of the Apes. A rare chance to see a depiction of the actual emergence of language in a new primate species in real time. I promise that very little of the plot will be spoiled if you read on.

Caesar, the hyper-intelligent genetically modified chimpanzee hero of the movie, after he finds his political consciousness and gets involved in organizing for liberation (that much you can see from the trailer), also finds his voice. And his first word is "No!" — roared rather harshly, but it's unimistakably that word. Strangely, the other apes seem to understand what he means, and he manages to stop them in their tracks.

This theory of language origins involves sudden emotion wresting from the organism a power it never knew it had. (I was reminded of the fact that there are people who honestly believe that if a speaker of British English had a moment of extreme emotion such as fear or anger, the affected British manner of speech would drop away and they would cry out in American English.)

Before the cathartic "No" there were plenty of signs that Caesar was beginning to understand what was said to him by humans. And there is also, extraneously, a small amount of conversation between Caesar and an ex-circus orangutan in what purports to be American Sign Language (heaven knows where Caesar was supposed to have picked up ASL, because the family in which he was reared didn't use it). And I cannot evaluate how accurately the ASL is rendered. I'd be most interested to have emails to my Gmail account from ASL-competent Language Log readers who can tell me how convincing it is: it will depend on how well the actors were rehearsed.

For we are talking about actors. Not actors in ape suits; but not trained apes either. The ape action in this movie was done via performance capture, by Weta Digital. The moving apes on screen are digitally created moving images of real ape bodies and faces that have been digitally animated in accord with records of movement generated (mostly) by the movements of real actors (see Wikipedia's article on motion capture or mocap).

When the cast list says that Andy Serkis (of Gollum fame) plays Caesar, it means that Weta took records of Andy Serkis in a mocap suit interacting with the human actors and used the records of his movements and facial expressions to animate the lifelike chimpanzee that appears in the film.

And I must tell you, the digital effects are extraordinary. There is major animation wizardry on top of the human acting (the parkour and structure-climbing goes way beyond anything that motion capture on human actors could provide). The apes are sometimes a bit too fast and nimble, maybe, and they have a strange immunity to cuts no matter how many plate glass windows they crash through, but these are some of the best scenes of animals doing things you will never be able to see them doing in real life since the Jurassic Park trilogy. If you should want to see forty or fifty apes kicking San Francisco's ass, and taking out police cars using manhole covers as frisbees, this is the film for you.

But back to the evolution of language. Caesar makes only one other intelligible spoken utterance in the film. It is a full clause, well enunciated, right at the end. Naturally students of the evolution of syntax will want to know the structure. It is what The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (CGEL) calls a complex-intransitive canonical clause, with copular be as its main verb.

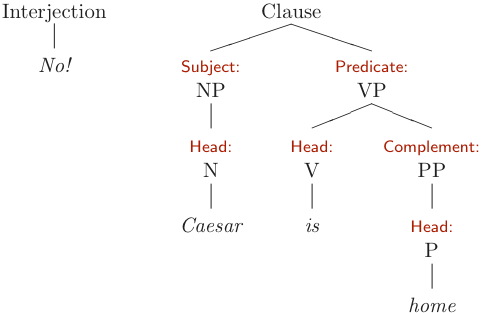

Since the Wikipedia article on the film quotes it, and nothing much hangs on it, I don't think you'll curse me if reveal it. The subject is Caesar (having not quite gotten the hang of pronouns, he refers to himself in the third person), and the copular complement would be analyzed by CGEL (following Ray S. Jackendoff, "The base rules for prepositional phrases", in Stephen R. Anderson and Paul Kiparsky (eds.), A Festschrift for Morris Halle, 345–356; Holt Rinehart and Winston, New York, 1973) as a preposition-phrase headed by an intransitive preposition, namely home. (Yes, home also occurs as a noun; but not here, I claim. Yes, prepositions are required to have noun phrase complements in traditional grammar; but CGEL explains why the tradition is mistake.) Here's my best shot at providing structures for the two utterances Caesar makes in the film:

There we have it: in this film's view of the evolution of spoken language the first utterance is No! and the second is a complex-intransitive copular clause with intransitive PP complement. From there on I presume it's plain sailing to full articulacy.

This is a small corpus, not much to go on. But since it's vastly more than we have available on the earliest utterances of Homo sapiens sapiens about 50,000 to 100,000 years ago, I thought you'd like to reflect upon it.

I wonder what the first things anyone ever said really were.

[Comments are closed. I was going to open them, but then I thought… No! Geoff is home.]