Hwæt about WH?

« previous post | next post »

In discussing his recent post about aspirated initial /w/ in Japanese pronunciation of English, Victor Mair asked about the historical phonetics of the strange English spelling 'wh':

I've tried repeatedly to pronounce the H part *after* the W and it seems to be virtually impossible to make such a sequence of sounds. What is it about the evolution of these WH- words in English that has led to this peculiar spelling? Weren't they all Q- words in Latin? Are they WH- words throughout Germanic? What would they have been in Proto-Indo-European?

Let's start by clarifying the nature of /h/, which involves noise created by turbulent flow of air through a small V-shaped opening at the rear of the vocal folds, with the front portion kept closed. In utterance-initial American English /h/, there's generally a short but well-defined voiceless period, and then the larynx is adjusted so that the turbulent flow is replaced by regular oscillation (i.e. "voicing") in the body of the vowel. But this laryngeal maneuver doesn't constrain the rest of the vocal tract — the lips, tongue, velum etc. are free to do whatever. And in an utterance-initial pre-vowel /h/, "whatever" means forming the pattern needed to make the vowel. In other words, the vowel articulation above the larynx is already completely in place before the /h/ noise starts.

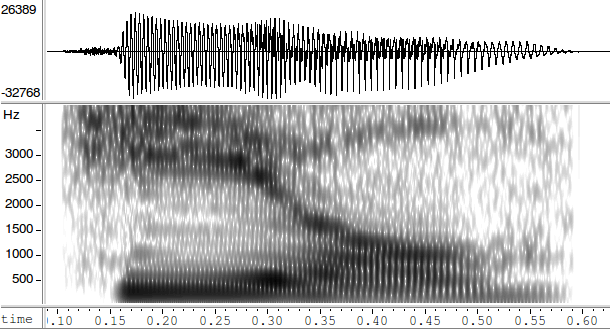

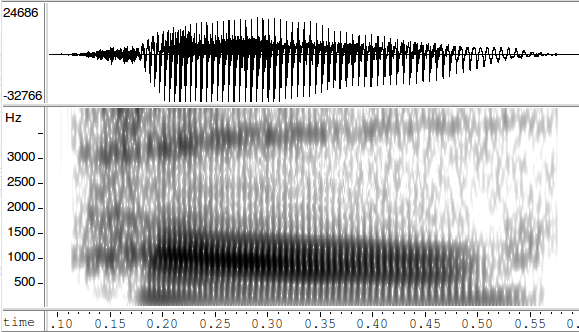

Thus the /h/ doesn't really "precede" the vowel, except in the sense that the glottal frication occurs at the beginning of the syllable. Rather, the /h/ is a feature of the way that the vowel starts. You can see this in the two plots below, showing spectrograms of citation-form pronunciations of heel and haul (from the Merriam-Webster online site):

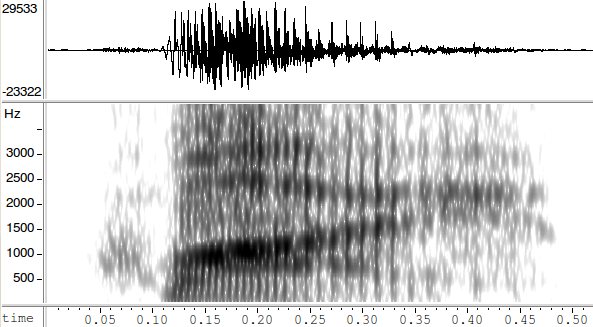

The situation is exactly the same for initial aspiration in a syllable starting with /hw/. There's an period of glottal frication during which the mouth is already in position for the /w/ — essentially, it's a voiceless /w/ with some turbulent-flow noise at the glottis. Here's why from the American Heritage dictionary at dictionary.reference.com (I didn't use the Merriam-Webster pronunciation since it's unaspirated):

So when Victor tried "to pronounce the H part *after* the W", he was trying to produce a voiced labiovelar approximant /w/, and then to stop the voicing and have a period of glottal frication, and then to start voicing again. At best, this requires the complex sequence of starting vocal-cord oscillation, stopping it in favor of glottal frication, and then starting voicing again (all within a tenth of a second or so), rather than just a simple voice onset after 50 or 60 msec of laryngeal turbulence. The biomechanics of voicing would make this rapid start/stop/start sequence a rather hard thing to do, I think; but in any case, it would be a violation of the usual ordering of articulations increasing in sonority from the start of a syllable to its core.

Gene Buckley observed:

The spelling hw in Old English reflects the phonetic reality quite nicely in its ordering, even if it's really a digraph for a single segment — phonetically it resembles a sequence of [h] plus [w], and so this would be a sensible way to spell it. I've long assumed that the re-spelling as wh in early Middle English was motivated by all the other digraphs that have h as their second element, e.g. ch, th, sh, due to Norman French orthographic influence. In other words, it was an orthographic analogy in spite of the better phonetic match in the older spelling.

And Don Ringe explained that

"wh" is a *purely* orthographic convention, and an especially stupid one at that. In Old English they consistently spelled this unit hw, which makes sense. I think it was a consonant cluster in OE, parallel to hr, hl, and hn (which became simple r, l, n in the 12th-13th c.), but in Proto-Germanic it was certainly a coarticulated sound–i.e., the "h" and the "w" were simultaneous– and the PIE labiovelar that it developed out of was also a coarticulated sound. (Opinions are divided about whether Latin "qu" was also a labiovelar or a sequence of /k/+/w/.)

Unfortunately, the phonological distinction between a doubly-articulated consonant and a cluster is not always phonetically plain — most consonant clusters are heavily co-articulated, and things that seem to be clearly single segments on phonotactic grounds (like aspirated stops in English, or /k͡p/ and /ɡ͡b/ in many African languages) nevertheless often have reliably sequenced sub-parts which correspond to things that might be independent segments in another context. This is one of many ways in which the "discrete beads on a string" nature of phonetic symbol sequences is articulatorily and acoustically misleading.

I should add that in the middle of utterances between vowels or other voiced sounds, English /h/ sounds are usually voiced rather than voiceless, i.e. IPA [ɦ] rather than [h]. This involves maintaining rapid quasi-periodic opening and closing in the anterior (front) portion of the vocal folds, while simultaneously creating noise via turbulent flow through a chink in the posterior portion. Again, the rest of the vocal tract is free to take on the configuration appropriate for the following vowel.

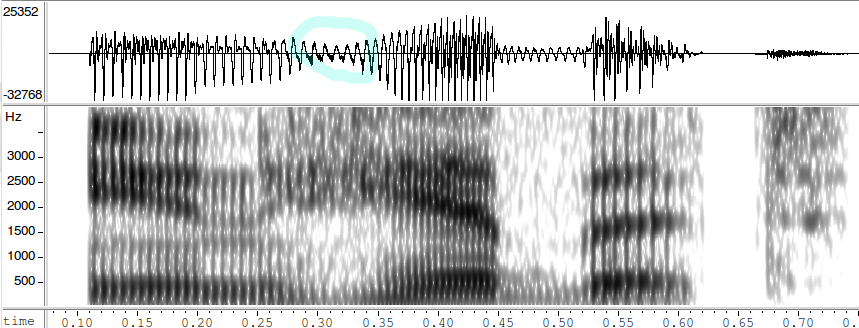

This is often true even in careful citation-form pronunciations, for example the online Merriam-Webster performance of inhibit, which you can see that the noise comes after the release of the [n], and indeed is fully established only after the formant transition to [ɪ] is largely complete:

richard howland-bolton said,

April 13, 2011 @ 6:42 am

"due to Norman French orthographic influence"

So, something else we can blame on the Bastard!

Merri said,

April 13, 2011 @ 6:48 am

Consonant clusters hl, hn, hw were present in Old Norse, and some other medieval Germanic languages, so it is no surprise to see them appear in English. But notice that the 'h' part seems to have represented a bit more than mere glottal frication – something like [ç].

noahpoah said,

April 13, 2011 @ 6:52 am

I wonder if there are dialects of English in which the aspiration/frication of 'wh' is labial. I think I've heard people produce it as a voiceless labiovelar fricative, but maybe it was just regular old 'h' aspiration…

Ast A. Moore said,

April 13, 2011 @ 6:56 am

Note, however, that the AHD has traditionally used speech synthesis for its audio. I cannot listen to the examples since I don’t have Flash installed, but their standalone software (eReference) uses audio files generated by a proprietary TTS (Text-toSpeech) engine.

[(myl) That is not true of the online version that I've used for this example.]

John Jameson said,

April 13, 2011 @ 7:00 am

How come the F2 for the second [ɪ] has such a sharp fall even though [ɪ] is a monophthong?

[(myl) Assuming you mean the /ɪ/ in the stressed syllable of inhibit — it's followed by a /b/, whose labial closure lowers all formants.]

Edman said,

April 13, 2011 @ 7:07 am

Victor asked: "Are they WH- words throughout Germanic?"

Danish and Norwegian keep the original order, but have HV- words rather than HW- words – for example, hvilken, meaning "which".

In Swedish, HV- words survived until the early 20th century.

Pflaumbaum said,

April 13, 2011 @ 7:18 am

What happened in the case of who? Presumably the rounded vowel in some way influenced the loss of the /w/, and it must have happened before the loss of the aspirated element in most dialects.

[(myl) I believe that it was hwa in OE, which turned into /hua/ on the way to /hu/. Or something like that.]

Donald Ringe's note about the controversy over the Latin /kw/ is interesting – I'd always thought it was clearly labiovelar like the reconstructed PIE equivalent. Can anyone summarise the evidence? I guess the fact that the /u/ can be syllabic in qu- words like cui suggests a cluster, and the /p/ reflex in some positions in Romanian suggests a labiovelar?

Simon said,

April 13, 2011 @ 7:26 am

Some Norwegian dialects pronounce the wh-words with kv- or k-, 'hvad' (what) becomes 'kva' or 'ka'.

Pflaumbaum said,

April 13, 2011 @ 7:33 am

@myl – Thanks. So much for my presumptions. Any idea then why it didn't partake in the general loss of the /h/ (or aspirated element) in wh- words?

Nick said,

April 13, 2011 @ 7:40 am

Can you do the same for PIE Laryngeals?

I'm having a hard time getting round how the words are pronounced.

Reading it, and hearing it are two different things.

Or is there a website that has audio with PIE words?

goofy said,

April 13, 2011 @ 8:40 am

So presumably Old English hl, hn, hr, hw were voiceless versions of l, n, r, w. What about wl and wr?

Pamela said,

April 13, 2011 @ 9:02 am

I'm curious about the coexistence in the USA of /w/ and /wh/ for words like "what". The /wh/ pronunciation seems to be more common in the southern US and among older speakers. Is there a historical explanation for this?

cameron said,

April 13, 2011 @ 9:04 am

In Northern England and Scotland the wh- words were often spelled quh- . Just about the last trace of that spelling is the word umquhile which was a favorite of Sir Walter Scott's. He presumably deployed it as a deliberately medieval and Scottish affectation.

Ran Ari-Gur said,

April 13, 2011 @ 9:11 am

@Pflaumbaum: In many words, historical /wo/ collapsed into /u/; not only "who(m)((so)ever)" and "whose", but also "whole", "[prostitute]", "sword", "two", and many others. (And if I understand correctly, the exceptions where we have /wu/ — words like "womb" — are cases where /w/ was later restored as a spelling pronunciation.)

Ellen K. said,

April 13, 2011 @ 9:17 am

@Ran Ari-Gur

Why, then, do 3 of the 6 words you list not have /u/ but rather /o/ or a rhotic variation thereof?

Ran Ari-Gur said,

April 13, 2011 @ 9:19 am

@Ellen K.: Because I wrote "/u/" when I meant to write "/o/ or /u/". :-P

(The rhotic point is a good one, and I have no idea. How come "sword" has no /w/, but "world" does? I don't know.)

John Lawler said,

April 13, 2011 @ 9:20 am

@Pflaumbaum –

The two interrogatives who and how both lost the labial rounding component of OE hw-, rather than the aspiration component. I've always assumed that this was because they were followed by back rounded vowels at the time, which would have absorbed the rounding, leaving only the aspiration. Because of vowel shifts, this is no longer completely true with how, but that's why historical linguistics is such a detective game.

GeorgeW said,

April 13, 2011 @ 9:33 am

@Pflaumbaum & John Lawler:

Could the Great Vowel Shift have played a role in this? The vowel in 'how' went from OE /uu/ > /au/.

David said,

April 13, 2011 @ 9:34 am

At some point, the /w/ sound was replaced by /v/ in Old Norse. In standard Swedish, /h/ was gradually lost in front of all consonants. It seems that /h/ was lost in front of /v/ during the 17th century at the latest. I think there are certain dialects where it would have survived longer. It was removed in spelling in 1906.

The exception is words containing "hvo-" where the /v/ was lost, cf. "hur" ('how') for Old Swedish "hworo" (I think the is a spelling convention and that the pronunciation would have been /v/).

In Western Norway, the dialects now written with Nynorsk, /h/ became /k/ in front of /v/, and then /v/ was lost between /k/ and /o/. So we get Nynorsk "kvit" for Swedish "vit" (pre-1906 "hvit") and English "white", and Nynorsk "korleis" for archaic Swedish "huruledes" ('in what way').

This, at any rate, is how I think it worked.

Matthew Moppett said,

April 13, 2011 @ 9:38 am

@Pflaumbaum: The collapse of the wh/w distinction is a pretty late development in English phonology (for those dialects – the majority – in which it has occurred). The loss of /w/ in 'who' would have occurred considerably earlier than this.

@Ran Ari-Gur: yeah, although some of your examples show a change from /wo/ to /o/ (like 'whole' or 'sword' – I think these ones typically had an open /o/ sound in Middle English rather than the close /o/ that usually gave rise to /u/ in modern English. The development of Old English /hwā/ to /hwo/ and finally /hu/ (who) parallels the Old English /twā/ –> /two/ –> /tu/ (two).

One nitpick: 'whole' is derived from Old English hāl; it has never had a /w/ in pronunciation – 'whole' is one of those pseudo-etymological spellings that sometimes crops up in English.

John Cowan said,

April 13, 2011 @ 9:56 am

The curious case of wr- was just discussed at John Wells's blog. In short, the result of the wring-ring merger was to leave all initial English r pronounced with lip-rounding.

dw said,

April 13, 2011 @ 10:00 am

I've tried repeatedly to pronounce the H part *after* the W and it seems to be virtually impossible to make such a sequence of sounds.

Marathi actually has a /wh/ sequence. I don't speak Marathi myself, but I believe that /h/ is realized as breathy voice, as in Hindi. Like most Indo-Aryan languages, Marathi has no /w/-/v/ contrast, and the actual realization of the labial probably varies freely between [w], [v] and intermediate sounds such as a labiodental approximant [ʋ].

I have heard Marathi speakers attempt to apply this articulation to English words spelled with "wh-" — for example "which" as [ β̤ʷɪt͡ʃ]

dw said,

April 13, 2011 @ 10:11 am

@Cameron:

The "quh" spelling probably represented a phonetic [xʷ], still preserved in some Scottish dialects. See, for example, the discussion here.

Mr Fnortner said,

April 13, 2011 @ 10:24 am

So, was the Scottish proper name Farquhar historically pronounced far-hwar?

Pflaumbaum said,

April 13, 2011 @ 10:34 am

@ Ran, John, George, Matt – thanks. I meant loss of the /w/ of course, not the /h/… what is it about this place that makes you check your post 8 times and still miss glaring errors?

@Nick – I think the reconstructions for PIE larngeals with the most current consensus have *h1 as a glottal stop, h2 as some species of back fricative, and h3 also a back fricative, probably voiced and possibly labialised. You can hear sound files of back fricatives on Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voiced_velar_fricative

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voiced_pharyngeal_fricative

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voiced_uvular_fricative

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voiceless_velar_fricative

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voiceless_pharyngeal_fricative

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voiceless_uvular_fricative

But in the end, I'm not sure guessing what they sounded like is an exercise with that much point. Laryngeals aren't real sounds, they're reconstructed phonemes.

[Apologies in advance for the inevitable glaring errors.]

languageandhumor said,

April 13, 2011 @ 10:41 am

Do most phoneticians these days consider the "hw" variety of wh to be the cluster of [hw] voiceless glottal fricative followed by voiced labial-velar approximate rather than the unitary [ʍ] (upside-down w) voiceless labial-velar fricative?

Lugubert said,

April 13, 2011 @ 10:50 am

@dw, on Marathi vh-:

Google Beckham tattoo. “Wife Victoria … was commemorated with the rendition of her name in Hindi script. Interestingly, some have claimed that this tattoo has a misspelling in it, noted as the inclusion of an "h." ” The tat transcribed is vhiktoria.

Eric P Smith said,

April 13, 2011 @ 11:18 am

@languageandhumor

I was wondering the same thing. I was born and brought up in Scotland, that bastion of [ʍ]. My pronunciation of 'what' is [ʍɔt] and nothing like [hwɔt]. It seems very strange to me to label the phoneme /hw/ and not /ʍ/.

Rodger C said,

April 13, 2011 @ 11:33 am

@Mr Fnortner: Farquhar is from Gaelic Fearchair, where ch is /x/ with phonetic labialization.

snow black said,

April 13, 2011 @ 11:38 am

Here's another attempt to pronounce wh as w then h.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YqgPyqyh4X4 at about 2:15

practik said,

April 13, 2011 @ 11:41 am

@Lugubert, or rather @ those who say Beckham's tattoo is misspelled:

When I was learning Nepali I found it very difficult to hear the difference between aspirated and unaspirated initial consonants. To Nepali ears, all my consonants came out aspirated, which my tutors confirmed was a common problem for American speakers of the language. So maybe "Vhiktoria" was the tattoo artist's faithful transliteration of what he heard.

Jongseong Park said,

April 13, 2011 @ 12:09 pm

@practik: I know little about Marathi or other languages of the region, but your theory sounds plausible. The sound in question seems to be /ʋʱ/, an aspirated labiodental approximant (which seems to be very rare even in the region). English /v/ is a full fricative, so the frication could very well lead to identification as an aspirated consonant for a Marathi speaker. I don't know how English loanwords are usually adapted to Marathi, but it wouldn't surprise me too much if /w/ tended to be mapped to Marathi /ʋ/ and /v/ to /ʋʱ/.

Of course, I expect this theory to be shot down any instant now.

Nick Z said,

April 13, 2011 @ 12:10 pm

@ Pflaumbaum: Lat. cui is probably the regular reflex of *kwoyyey- in unstressed position, with loss of labiality in *kw before a rounded vowel and raising of *-o- to /u/ (cf. attested older spellings like QVOIEI and quoi). So the -u- in cui probably has nothing to do with the question of whether /kw/ was co-articulated or not in Latin.

D.O. said,

April 13, 2011 @ 12:48 pm

Can anybody, please, explain a bit the spectrograms. What features are responsible for /h/ sound?

mollymooly said,

April 13, 2011 @ 1:06 pm

Farquhar /k(w)/

Urquhart, Sanquhar: /k/

Colquhoun: /h/

Balquhidder, Kennaquhair, Kilquhanity : /ʍ/

Kilconquhar: /x/

Not quite -ough- but not bad.

Ann said,

April 13, 2011 @ 1:16 pm

@practik

IANAL BIME (I am not a linguist but in my experience)

At least in Nepali (and Hindi may be different) the letter he used is the standard one used to transcribe the English "V." It generally sounds like "Bh" to English speakers but sometimes "V" or "Vh". The only other options are 1) a letter that usually sounds like "W" to us, sometimes "B" and very rarely "V", or 2) a letter that sounds like "B" (and I personally have never heard it sound like "V"). So I don't think he had a better option.

Sorry for the vagueness; I can't figure out how to include Devanaagari characters in this comment.

Ian Preston said,

April 13, 2011 @ 2:59 pm

@Jongseong Park: My impression from time spent in Maharashtra is that the व्ह cluster is certainly sometimes used to distinguish a /v/ from a /w/.

I share the opinion that the criticism of Beckham's tattooist is misplaced. My Marathi dictionary has an entry: व्हिक्टोरिया f A buggy; a horse-drawn vehicle for three. Proper name of a famous queen of England.

The Marathi Wikipedia entry on Victoria Falls for example spells the name exactly as on his arm as does the entry for Queen Victoria (which I can't get to link properly). There's no entry for Victoria Beckham herself but the rather brief entry on David Beckham uses the same transliteration for the /v/ in his name.

Peter said,

April 13, 2011 @ 3:22 pm

Taking a rather different tangent from the post: is it just me, or is the M-W “inhibit” clip also a perfect demonstration of how a New Zealander would pronounce “inhabit”?

Tom Recht said,

April 13, 2011 @ 4:20 pm

@Ran, the way I've heard the /w/-loss story is that /w/ was only lost before /o/ if a consonant preceded, i.e. in the sequence /Cwo/. This would account for why there's still a /w/ in 'world', but not in 'sword' – or in 'who', assuming that /hw/ was indeed a cluster at the time of the change.

@Pflambaum, re Latin /kw/: I think the strongest evidence that QU stands for a single labiovelar phoneme is that it doesn't make position, i.e. doesn't count as a cluster for prosodic purposes (stress assignment, meter). I too am curious what the contrary arguments are; maybe someone more knowledgeable will enlighten us.

Pflaumbaum said,

April 13, 2011 @ 4:29 pm

Interesting stuff, Nick Z.

So if quis (the lexeme) had alternation between /kʷ-/ and /k-/, is QVOIEI most likely to represent the archaic pronunciation, levelling of the paradigm towards /kʷ-/, or just the scribe's confusion?

Rohan Dharwadkar said,

April 13, 2011 @ 5:04 pm

As a native speaker of Marathi, I can confirm that the frication of English /v/ does indeed tend to be represented in Marathi orthography and speech by tacking the pseudo-fricativity of aspiration onto the most similar native phoneme (i.e. /ʋʱ/).

Marathi also has aspirated nasals and liquids, which aren't found in, say, Hindi. Maybe it's because of this ubiquitousness of phonemic aspiration that I don't find it particularly difficult to pronounce /vʱ/ and /wʱ/

An aside: Marathi strikes me as being pretty weird as far its affricates are concerned: it has [ts], [tʃ], [tʃʰ], [dʒ], [dʒʰ], [dz], [dzʰ] but not [tsʰ] (not sure if these are phonemes or allophones; my intuitions hint at phonemicity). Whyever not? Quite a salient pattern incongruity, that is.

Pflaumbaum said,

April 13, 2011 @ 5:30 pm

@ Tom – good point about the prosody. Also I guess the fact that they retained a separate symbol is some supporting evidence. Are there many inscriptions with cu-, or q-, for qu-?

@ Rohan – this is just Wikipedia, but it has a hypothesis:

'Aspirated *tsʰ, dzʱ have lost their onset, with *tsʰ merging with /s/ and *dzʱ being typically realized as an aspirated fricative, [zʱ].'

George Amis said,

April 13, 2011 @ 7:09 pm

@mollymooly Apparently, at least some people pronounce Farquhar with /x/.

@Roger C and Mr Fnortner An alternate spelling is Ferchar. The full name of the first Earl of Ross is Ferchar mac an tSagairt, which is Anglicized as Farquhar MacTaggart. So quh is an English, not a Gaelic form.

(I have an American friend named Farquhar who pronounces her name /ˡfɑrˡkwɑr/ with almost level stress.)

GeorgeW said,

April 13, 2011 @ 7:26 pm

FWIW, Watkins ("The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots") says that PIE /kʷ/ goes to Latin /qu/, Germanic /hw/, Old Persian /k/, etc.

It shows *kʷo and *kʷi are the stem of the English /wh-/ words like who, what, why, when, where, etc. (I guess without this, we would be stuck today with only yes-no questions to ask. )

Ray Dillinger said,

April 13, 2011 @ 8:11 pm

Okay, I'm not really a linguistic historian — I just write (Modern English) language-interpretation software. I'm familiar since childhood with some older dialects of English. And I speak some French, but not well enough to write software to understand it.

You guys who have actually studied linguistic history and ancient languages, please riddle me this: What the heck is our basis for thinking we know anything about Proto-Indo-European?? In my experience a dialectical difference of only 3 centuries can render someone incomprehensible to those who are not listening carefully. I observe the speed and apparent arbitrariness of linguistic change in living languages, and then consider the time span involved between the early PIE languages we actually know and the supposed existence of PIE proper, and I cannot understand how we can have any real knowledge of a real language language spoken in that era.

Given the time spans involved, and the general rate of linguistic change we observe in living languages, spoken languages would have changed as far as modern English from old Greek, and back, several times in the span we're talking about. The small set of linguistic changes we have generally accepted (and the back-constructed vocabulary) seem completely out of proportion to the huge time period involved.

Thus, when I hear someone talking about "PIE roots" and "PIE sounds" I'm always wondering whether his "PIE" is some kind of well-understood historic fact, or just a currently popular consensus built out of phantom patterns in effectively random data.

Atmir Ilias said,

April 13, 2011 @ 8:38 pm

English-Albanian:

What=çfar,ça,çë?

Who=kush

When=kur

Where=ku

Whack=rrah,

Whale=balen

Wham=bam

Wham bam=bam bam

Wheat=where eat=ku ha

Wheedle=ledhatoj

Wheeze=gulç, gërhas

Whelp=wh’help=kulish, kylish (Homer)

Whether=qoftë

Whetstone=grihë

Whey=thartir

Whiff=grahmë

Wh’im=(Italian)fisima

Whine=klaj=qaj

Whip=fshik

Whir=uturin, zhurm

Dw said,

April 13, 2011 @ 9:41 pm

@Ray Dillinger:

You may want to look back at this older Language Log post by Don Ringe

The basic answer to your question is that we have a very large number of daughter IE languages to compare, with records going back to the mid-2nd millennium BC(E).

Bloix said,

April 14, 2011 @ 12:02 am

Not to lower the tone of this discussion, but – YOU'RE EATING HAIR!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lich59xsjik&feature=related

SmR said,

April 14, 2011 @ 3:23 am

Not to detract from the hw/wh-discussion, but if the first word of the title is supposed to be "what", I think the vowel is wrong.

Pflaumbaum said,

April 14, 2011 @ 3:35 am

@ Ray Dillinger –

Your instinct is both right and wrong. Quite a lot is known about PIE, because of the (I think remarkably) regular nature of language change. For instance, previously unattested words, predicted for a daughter language by working forward from PIE, have subsequently been discovered in texts written in that daughter language. That's as close to proof as you can get in a historical science.

But PIE was not a spoken language, and its reconstructed phonemes are not 'sounds'. My former supervisor James Clackson explains it well in his book Indo-European Linguistics: an Introduction –

"Reconstructed PIE is a construct which does not have an existence at a particular time and place (other than in books such as this one), and is unlike a real language in that it contains data which may belong to different stages of its linguistic history. The most helpful metaphor to explain this is the ‘constellation’ analogy. Constellations of stars in the night sky, such as The Plough or Orion, make sense to the observer as points on a sphere of a fixed radius around the earth. We see the constellations as two-dimensional, dot-to-dot pictures, on a curved plane. But in fact, the stars are not all equidistant from the earth: some lie much further away than others. Constellations are an illusion and have no existence in reality. In the same way, the asterisk-heavy ‘star-spangled grammar’ of reconstructed PIE may unite reconstructions which go back to different stages of the language. Some reconstructed forms may be much older than others, and the reconstruction of a datable lexical item for PIE does not mean that the spoken IE parent language must be as old (or as young) as the lexical form."

Nick said,

April 14, 2011 @ 3:41 am

@SmR It's the Old English spelling, not IPA.

A Reader said,

April 14, 2011 @ 5:22 am

Pfllaumbaum, what Clackson says ought to apply well enough to pre-PIE (i.e. anything adduced through internal reconstruction), but anything gained through direct comparative reconstruction should have to have been a part of PIE proper. You shouldn't have a feature that 'leapfrogged' over PIE proper (i.e. the actual common ancestor of all the daughter languages).

I think the vagueness comes more from our very real uncertainty about the internal structure of the family (especially the position of Anatolian), and our tendency to gloss over the difference between comparative and internal reconstruction. Clackson is cautious in this area, as are many Indo-Europeanists, but I think it's possible to overstate the case here.

Dylan said,

April 14, 2011 @ 9:30 am

Fun read – thanks. I think I'll take this to my historical linguistics class this morning.

Eimear Ní Mhéalóid said,

April 14, 2011 @ 12:40 pm

"Hw" must have been a difficult sound for Irish speakers to produce, or at least not in their repertory, as surnames such as de White/Whyte were translated as "de Faoite", and words like "Whig" translated "Fuig".

One of my grandfathers, from the West of Ireland but a monoglot English speaker, always referred to a particular well-known snooker player as "Jimmy Fwite".

mollymooly said,

April 14, 2011 @ 1:34 pm

@Eimear Ní Mhéalóid

A joke of my father's, said in a Kerry accent: "In Tyrone they call a [ˈfwɪʃl] a [ˈvɒsl]" (i.e. "whistle")

Seems also to apply to /w/, e.g. "window"–>"fuinneog"

But OTOH Irish English is one of the few dialects retaining the /wh/–/w/ contrast.

Conversely, why was "uisge (beatha)" anglicised "whisk(e)y" rather than "wisk(e)y"? In Ireland today we have /hw/ in "whiskey" but ∅ in "uisce".

Atmir Ilias said,

April 14, 2011 @ 9:31 pm

What you implied, it is the weak of the phonetic method. No linguist could provide an answer to question about the amount of time that the set of linguistic lasts?”, but it does not mean that the linguists must stop the research.

But some Irish words are very, very interesting. The word Irish for water is /uisge /, while the Albanian word for water is “ui”. It becomes much more interesting, because the Chinese word for water is 水, Shuǐ.

Whiskey sounds to me that it is a refreshing of language against the phonetic transformations. It's very known the weight of the "w" sound. It is like a double stop that if you add a "H”, it becomes a triple stop.

But it is not very well-known why the spooken languages tend to eliminate them, which is also the cause of their destruction.

Atmir Ilias said,

April 14, 2011 @ 9:35 pm

Sorry. The first paragraph was directed to Ray Dillinger –

maidhc said,

April 15, 2011 @ 5:03 am

"uisge" is the standard word for water in Irish, but in some dialects you get "fuisge". Other words work similarly, like the standard "oscail" (open) can be "foscail".

The sound change called séimhiú (lenition), which in the old Irish alphabet was represented by a dot over the letter, but in the new spelling is given as an added H, transforms F into FH, which is silent. So the loss of initial F is not surprising.

As mollymooly added above, the F and W sounds have a tendency to relate (the version I heard was "they call a fwip a whup").

So it is not too surprising that "fuisce" would develop into "whiskey".

Maybe going further back, this is related to the P-Celtic vs. Q-Celtic thing. Original IE forms like "pater" end up in Irish as "athair" because the P got lost. American Heritage Dictionary says the IE root of "uisce" is WED1. Makes me wonder if it is related to "piss". P, PH(F) and W seem to be relatives.

army1987 said,

April 15, 2011 @ 5:07 am

"Whiskey" was borrowed back into Irish as "fuisce".

(/fˠ/ is/used to be bilabial in some environments/dialects/speakers.)

army1987 said,

April 15, 2011 @ 5:15 am

"fuinneog" does not come from "window", they both come from Old Norse "vindauga".

John D said,

April 15, 2011 @ 5:20 am

@languageandhumor

@Eric P Smith

I've heard another Scot say the same thing, that /hw/ seems a strange way to transcribe this sound. I'm not a phonetician, but as yet another Scot, I agree. I would transcribe "what" as /ʍɔt/, not /hwɔt/. In my mind, it's a single sound, and /hw/ suggests there is a sequence of sounds. I'd be interested to hear the intuition of ʍ/hw speakers from elsewhere. What do the Americans who produce this sound think?

army1987 said,

April 15, 2011 @ 5:21 am

(well, if fuisce means “water” in some dialects, I think it's quite unlikely for the F to be the result of reborrowing from English, as I had assumed.)

Rodger C said,

April 15, 2011 @ 7:37 am

A good number of Old Irish words beginning in a vowel have f+vowel in modern Irish. This is a back-formation from the lenition f > zero, mentioned by maidhc.

Bloix said,

April 15, 2011 @ 4:57 pm

And as for PIE, see

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lich59xsjik&feature=related

Anthony said,

April 17, 2011 @ 10:36 am

Even for an amateur (like myself), it's easy to see how a word like "who" lost its 'w' sound – it's very easy to elide the /w/ in combinations /wo/ and /wu/; it's not surprising to see /hwo/ become /ho/, then, through vowel-shifting, become /hu/.

Semi-relatedly, Charles Dickens attests the loss of the /h/ in certain lower-class London speech by the early Victorian era – in "The Pickwick Papers", both Sam and Tony Weller are written as saying "wy" for "why".

David Marjanović said,

April 17, 2011 @ 6:44 pm

Aren't there Americans who pronounce wh as [xʷ]? Or was that Family Guy episode just wrong?

Evidence for Latin qu having been a unitary phoneme: it didn't participate in the shift of /w/ to [v]. V is [v] in Italian, but qu and gu have stayed [kʷ] and [gʷ].

Related to German heil.

I wonder if whore is another one of those. After all, in German it's Hure.

And I wonder if Slavonic /kurva/ (same meaning) is related to that…

Matthew Moppett said,

April 18, 2011 @ 2:44 am

@David Marjanović:

You're right about whore – from Old English hore, with the wh- spelling innovated in the 16th century. I don't know about /kurva/, but the proto-Germanic form was apparently *khoron, derived from PIE *qar- (my information is obtained from a great little web resource called the Online Etymology Dictionary, http://www.etymonline.com/index.php).

Jonathan said,

April 18, 2011 @ 9:43 am

anyone seen the movie Hot Rod?

"my safe word will be hwiskey"

Anthony said,

April 20, 2011 @ 9:42 am

@David – one of my elementary school teachers in Delaware tried to get us to pronounce "wh" as /hw/, but it pretty much didn't take. (And completely failed with me.)

Bob Violence said,

April 21, 2011 @ 5:20 am

Just want to say I've been watching some Norm Macdonald lately and he seems to use /hw/, though far from always — there's some examples in this clip. Now I'm wondering if his brother does the same thing.

David Bloom said,

April 22, 2011 @ 7:15 pm

Anybody want to blame the Romans for inventing rh- to match ph-, ch- as equivalents for Greek letters? It seems like a mistake in exactly the same way as wh-.

Jeff Adams said,

June 2, 2011 @ 4:12 pm

I grew up in East Texas in the less-merged area indicated on the map in Wikipedia's article on the wine-whine merger. What I say and what I hear from others is /ʍ/. I don't really think /hw/ is a fair representation of the sound, and if it was, I think it would be much more noticeable in speech and that the wine-whine merger would consequently be so conspicuous that it would never have caught on. On the rare occasion that somebody with a merged pronunciation notices and comments on the fact that I don't use /w/, however, they will imitate what I say with /hw/ or even the very-Spanish sounding /xw/.