Annals of "No word for X"

« previous post | next post »

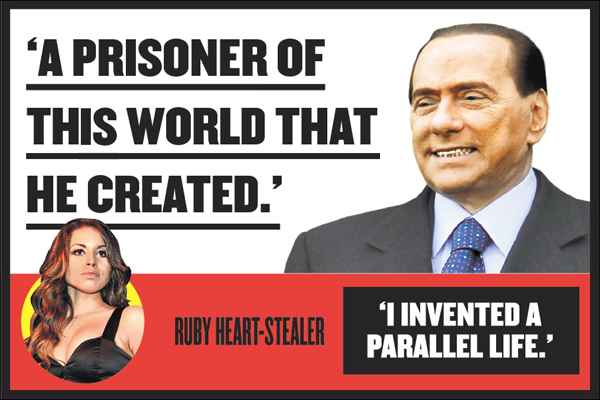

An unusually fine example in Rachel Donadio, "Surreal: A Soap Opera Starring Berlusconi", NYT 1/22/2011:

An unusually fine example in Rachel Donadio, "Surreal: A Soap Opera Starring Berlusconi", NYT 1/22/2011:

It is not always easy to translate between Italian and American sensibilities. There is no good English word for “veline,” the scantily clad Vanna White-like showgirls who smile and prance on television, doing dance numbers even in the middle of talk shows. And there is no word in Italian for accountability. The closest is “responsibilità” [sic] — responsibility — which lacks the concept that actions can carry consequences.

As it happens, we've already covered the "No word for accountability" instance of the "No word for X" meme ("Solving the world's problems with Linguistics", 12/16/2006), in a post where we learned from international bankers and others that there's no word for accountability in any of the Romance languages (including specifically French and Italian), in Russian, in the languages of most if not all of the countries served by the Asian Development Bank (including specifically japanese and Chinese), in Modern Hebrew, in Bemba, and so on. A quick web search will turn up additional specific references to the lack of (a word for) accountability in Spanish, Portuguese, Finnish, Kedi, Swedish, etc., with others no doubt waiting on the next published after-dinner speech about the banking system in Iceland or Mongolia.

In fact, it's possible that only English-speakers can grasp the concept of accountability, at least if we accept that no one could possibly understand an idea that they need an expression longer than one word to name, or some context to interpret. The French, for example, would need to talk about having comptes à rendre, requiring three or even four words. This same limitation may explain why it's so difficult for us English speakers to get our minds around things like reforming the health insurance system, since we need five or six words even to refer to the issue.

(To avoid being misunderstood by commenters who don't follow links, I guess I'd better point out that the last paragraph was meant ironically…)

A partial list of LL posts on this topic can be found here.

[Tip of the hat to Ben Sprung]

[Update — the WordReference entry for responsabilità gives three senses, corresponding roughly to English "responsibility" (in the sense of being in charge of something), "guilt" (for which colpa is also a possibility), and "liability", as in società a responsabilità limitata "limited liability company". Along with combinations like responsabilità civile "civil liability" and responsabilità penale "criminal liability", the third sense certainly seems to involve the notion that "actions can carry consequences".

And as in French, there's no difficulty in deploying the specific idea of needing to answer to someone: dover rispondere a __, or dover rendere conto a __.

So it's true that Italian uses the same (single) noun for being in charge of something and being answerable for something — and distinguishes the senses by adding modifiers as contextually required, or uses verbal paraphrases where the idea of being answerable is to be made explicit in more detail. It's not clear that this has anything to do with the cultural, social, political differences behind the way that Berlusconi's scandals are treated.]

[Update #2 — in the comments, Licina points us to the EU inter-institutional terminology database, which renders accountability in Italian as attendibilità, responsabilità, or assunzione di responsabilità. The translations into Spanish are obligación de rendir cuentas, responsabilidad, and rendición de cuentas; and into French, responsabilisation (which seems to be a neologism), obligation redditionnelle, obligation de rendre compte, and responsabilité.]

John Lawler said,

January 23, 2011 @ 3:55 pm

In this context I should probably mention Anna Wierzbicka's 2006 book English: Meaning and Culture (Oxford U Press), which certainly has a place in these Annals, as a glance at the Contents pages linked above, and a recent blog post on the book show.

[(myl) And a somewhat older blog post here: "No word for fair?", 1/29/2009.]

Twitter Trackbacks for Language Log » Annals of “No word for X” [upenn.edu] on Topsy.com said,

January 23, 2011 @ 4:00 pm

[…] Language Log » Annals of “No word for X” languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=2920 – view page – cached January 23, 2011 @ 3:09 pm · Filed by Mark Liberman under Language and the […]

brdo said,

January 23, 2011 @ 4:19 pm

Everyone in Italy knows what a velina is. Even if you gave me an unlimited amount of time to do so, there is no way I could possibly make you understand the meaning of the word in the same way an Italian understands it. That would require watching several hundred episodes of a program called "Striscia la notizia", and understanding all of the jokes and cultural references. There was an article in Newsweek recently where the author (presumably resident in Italy) demonstrated a complete failure to understand the ironic aspects of the veline – and as a result Newsweek has justifiably become the butt of a running joke on the program.

As far as the difference between "responsibility" and "accountability" is concerned, I once attended a meeting of judges in an eastern European country. A speaker who came from the US (at significant expense) started his speech as follows; "I would like to discuss two important and interrelated concepts: responsibility and accountability" He went on in this vein for several minutes. I noticed that the translator was using the same word for both concepts. We asked the speaker to stop his speech and then he, I and the translator huddled together to try to come up with two different words. We couldn't, and the speaker had to toss out his prepared remarks and talk about another subject.

This is a true story. This is what people who have to work with translation deal with all of the time. There is a fundamental difference between the concept of a "word" and a thing that can be described or explained given enough time. The point you make (over and over again) may be true in some abstract sense, but when people say "there is no word for x" they are describing a real fact about real life in the real world.

Jean-Sébastien Girard said,

January 23, 2011 @ 4:31 pm

(French-Canadian speaker here)

The problem is that only the US can come up with a worldview where accountability and responsibility even SHOULD be separate concepts. The problem starts with the statement that "[term from the root of] responsibility […] lacks the concept that actions can carry consequences."

In my mind, it goes exactly the OTHER way around: responsibility ("responsabilité") carries exactly THAT. "Accountability" is paperwork: it's the track record of who decided what and thus bears the responsibility. Responsibility exist independently from accountability, and in a truly responsible system, there is no NEED for a separate concept of accountability, which seems thoroughly ingrained with a tendency to dodge responsibility. The very idea of splitting whatever accountability is supposed to be from responsibility seems so many levels of wrong…

Yes, I'm verging into pop-whorfianism a bit here, but o outside observers, this definitely feels like this.

Mr Fnortner said,

January 23, 2011 @ 4:44 pm

Mindful that the traditional definition of responsibility includes a strong component of accountability, in English today, I (and probably many others) distinguish responsibility as who does the work, and accountability as who gets fired.

michael farris said,

January 23, 2011 @ 4:56 pm

"when people say "there is no word for x" they are describing a real fact about real life in the real world."

This.

I live in Poland and there are many concepts where 'a word' (or more) might exist for a concept (going one way or the other between Polish and English) but the real, gut meaning can't be transferred in any meaningful way within the kind of context that translator work in.

Kylopod said,

January 23, 2011 @ 5:01 pm

@brdo

I think we need to make a distinction here between concrete and abstract. I don't know what a "velina" is, but then that's simply because I've never been exposed to it. If American TV programs started imitating the Italian ones in droves, we might then be tempted to borrow the word. It's like observing in the 18th century that English speakers have no word for spaghetti and therefore couldn't possibly understand the concept. Of course they couldn't–that is, until the stuff entered their culture and they needed a word for it, and they simply borrowed the Italian word.

Where this issue really gets tangly is when people start claiming that the absence of a single word for an abstract quality–responsibility, compromise, fairness, you name it–is evidence that the people who speak that language must be lacking in that quality.

David Eddyshaw said,

January 23, 2011 @ 5:14 pm

I suspect the peddlers of this particular one have some dim folk memory of Ruth Benedict's shame/guilt society thing at the back of their minds with responsibilty standing to shame as accountability to guilt. (This would account for it turning up so readily in reference to Japan.)

I don't think these people are really trying to make a point about language at all; it is just a handy piece of rhetoric for getting at those wacky foreigners, who fall so far short of our Anglophone wonderfulness. Casting it as a bogus linguistic point is just a way of trying to get the insult under the radar, and the evident fatuity is not therefore important to them.

There are people who do not comprehend that their actions have consequences; they are the field of study of psychiatrists, psychologists and criminologists rather than anthropologists, however. Much less linguists.

Dan Lufkin said,

January 23, 2011 @ 5:23 pm

One might note that Italians also had no word for spaghetti until Marco Polo, it is said, brought pasta in from the Orient. Then they decided to call it "little strings". We Anglophones could have gone with "stringies," I guess, but it never caught on.

Think of English — before about 1300, they had nothing that needed to be called "orange".

Interesting article in this month's Scientific American about language and perception. I look forward to some good discussion here.

Ben Hemmens said,

January 23, 2011 @ 5:33 pm

That's why Ireland is so much better off than Italy or Spain: they have a word for accountability ;-) Having the word is one thing, having a clue what to do with it seems to be another.

Factually, the bits of Italy I know are very tidy and functional, so somebody must be doing their job as though it mattered.

ShadowFox said,

January 23, 2011 @ 5:42 pm

One could argue (as has been partially expressed above) that the distinction between accountability and responsibility–in the same context–exists in American English because American like looking for scapegoats. So it doesn't matter who's responsible as long as someone is held accountable. The other distinction–responsibility as in "duty"–is simply a different gloss. Both words can mean the idea of someone being answerable for his decisions or actions–and this is easily translatable into, say, Russian. In fact, two different meanings of the verb for "be responsible for X" have slightly different corresponding words in Russian "otvechat' za X" and "nesti otvetsvennost' za X". In fact, the middle word in the second expression is the exact translation for "accountability" AND "responsibility" where the two really do mean the same thing. And, I am sure, Russians would complain that English does not have a simple word for that–so it has two instead.

Craig Russell said,

January 23, 2011 @ 5:42 pm

Brdo raises something of an interesting point: while it may be true that speakers of languages without "a word" for a concept are totally capable of understanding that concept, the lack of a single, repeatable word for that concept can alter the way we discuss the concept.

I work on ancient Greek literature, and I can think of several cases where translating e.g. Plato is extremely difficult because of this issue. Several of Plato's dialogues center around whether or not something (like rhetoric) is a "techne" (τέχνη). The earliest and most primary meaning of τέχνη in Greek literature is "skill", but in the fifth and fourth centuries it has come to mean an area or field where systematic, scientific knowledge can be applied to doing or making something (e.g. horsemanship, medicine, weaving). Τέχνη can also mean the set knowledge that one uses in one of these fields, or a written instruction manual explaining one of these fields.

In translating these dialogues it would be ideal to use a single English word consistently to translate τέχνη — often the word "art" is used, which is problematic for a number of reasons; really, the word needs several translations for different contexts. But beyond making Plato difficult to translate, this problem highlights a fact that seems relevant to this discussion: for a fifth/fourth century Greek interested in reaching a precise definition of truth and reality, and in understanding the nature of the world, it was very important to establish that poetry and rhetoric are not τέχναι, and thus in some sense not reputable or trustworthy. Philosophical debate is centered around the fact that the Greeks "have a word" for τέχνη, which we do not. That's not to say that English speakers can't understand Plato, of course — just that it's not a conversation we'd be likely to have.

David Eddyshaw said,

January 23, 2011 @ 5:51 pm

@Craig Russell:

It's been said that much mischief has resulted in Western philosophy from the fact that Greek, like most of the languages of Europe to this day, uses the same word for "exist", "be (something)" and "be (somewhere)".

Alas, I know too little of the subject to know if this is actually true …

Manuela said,

January 23, 2011 @ 6:23 pm

brdo,

how come then that I am Italian and I am perfectly able to see that Berlusconi is a corrupt thug? How about the millions of Italian like me?

As for the veline, their "ironic aspect" is not obvious to many Italians, and yet we all know what velines are. (I for one think that there's nothing ironic about them, or the program for that matter).

Peter Taylor said,

January 23, 2011 @ 6:30 pm

Jean-Sébastien Girard's comment reminded me of a famous Gordon Brown quote, which I'm sure someone mischievous could use as evidence that English lacks a word for responsibility:

[(myl) Indeed. For those who (like me) missed this the first time around, the full story is here:

]

hanmeng said,

January 23, 2011 @ 6:59 pm

I thought the word for "reforming the health insurance system" was "Obamacare".

J Lee said,

January 23, 2011 @ 7:02 pm

Mr. Girard could just as easily have concluded that since 'responsibility' and its reflexes already include the concept of an official determination of fault and its appropriate punishment, the introduction of a second term which refers to it more specifically is a manifestation of the same American ideal of individuality (which, if I were as fond of absurd generalizations as he, I might say Europeans completely lack) found in such widespread political phrases as "the buck stops here."

I also fail to appreciate the motivations of whoever you suppose to have fabricated the new term (presumably bureaucrats and politicians). More terms for more nuanced forms of culpability can only hurt them or anyone else in an organization, as we recently saw when an anti-gun control politician in Alaska purportedly influenced a homicidal maniac in Arizona with the standard military metaphors from which most political terminology is borrowed. Some claimed she was 'responsible' for a political climate conducive to violence; anyone who said she must be 'held accountable' for the shooting is simply misusing the term for rhetorical effect.

Christopher said,

January 23, 2011 @ 7:17 pm

The earliest and most primary meaning of τέχνη in Greek literature is "skill", but in the fifth and fourth centuries it has come to mean an area or field where systematic, scientific knowledge can be applied to doing or making something (e.g. horsemanship, medicine, weaving). Τέχνη can also mean the set knowledge that one uses in one of these fields, or a written instruction manual explaining one of these fields.

So, we do have a single word for it (Science or technique would also seem to approximate it pretty well in one word), but it lacks some of the connotations it had in Plato's Greece, and these connotations are important but difficult to explain easily to modern English speaking audiences.

I think that's just a problem of translation in general (And probably especially in philosophy, which tends to use broad concepts in very specific ways), and I'm not quite convinced that the existence or lack of a single word for a concept has anything to do with whether the concept can be easily translated and understood by foreigners.

And actually, the question of whether something can be easily understood is distinct from whether it can be easily translated. You've given a pretty good capsule of what "τέχνη" means, and it doesn't seem particularly alien to our modern culture (It's the distinction between an art and a science, more or less?), but you can't very well insert that explanation into every sentence where Plato uses that word.

Licia said,

January 23, 2011 @ 8:05 pm

I think it's quite interesting to search IATE (EU inter-institutional terminology database) to see the terminology used by EU translators to render accountability into the official EU languages.

And if you look up the more traditional meanings of velina, the English equivalents you get are tissue paper and carbon copy (is the noun flimsy still used in English?), which was also journalism slang for "press release". The scantily clad showgirls were named veline because they used to deliver printed copies of the latest news [veline] to the show hosts. The word velina has quite a few connotations, the strongest of which is definitely "flimsiness"…

Harold said,

January 23, 2011 @ 8:17 pm

"Accountable" is an English business or legal term clearly taken from Latin. In the Latin languages, "rendere i conti" (It.) or "comptes a rendre" (Fr.) would serve very well, I think.

Chris said,

January 23, 2011 @ 8:25 pm

There's a difference between explaining and translating. There are plenty of expressions in Mandarin whose meaning I understand, and could explain well enough in English, but if asked to translate a passage containing them I'd be hard pressed to find a suitable expression (one-word or otherwise)- one with a range of meaning suitably similar to the original, which sounded natural in English and didn't lose any of the connotations a Chinese speaker might see in the original.

Of course, none of this gives any more credibility to the silly idea that Italians can't understand accountability.

Licia said,

January 23, 2011 @ 9:00 pm

@ Harold – in Italian maybe rendere conto (e.g. rendere conto ai cittadini, rendere conto delle proprie azioni) but not rendere i conti, which means something like "return the accounts".

chris said,

January 23, 2011 @ 9:02 pm

@ brdo

What exactly was the core argument that the speaker from the US was trying to make in his lecture on "responsibility" and "accountability"? By the sounds of it, his argument was probably entirely reliant on the way those two particular terms are used in American English. In other words, his whole lecture was probably discussing a semantic issue entirely specific to English speakers, and possibly even just English speakers in North America. As Jean-Sébastien Girard's remarks suggest, that whole issue would be completely irrelevant to people from many other cultures. Which makes me think that the real problem here was not one of translation; the problem was that the speaker was giving a speech which had no relevance for his non-English-speaking audience in the first place. And that is another major difficulty that people who have to work with translation deal with regularly: having to translate texts which have not been adequately "internationalized" in the first place, i.e. which have not been written with adequate consideration of their intended foreign audience/readership.

bronrob said,

January 23, 2011 @ 10:09 pm

There seems to be undue emphasis on finding a single word to word correspondence when translating. Surely the aim of translation is to convey meaning. So what is wrong with 2 or more words if it makes meaning precise? eg accountability in French can translate as 'répondre de qqch à qqun', the equivalent in English, I guess, to 'answer for'.

Hermann Burchard said,

January 23, 2011 @ 11:51 pm

In German wie have 'Verantwortung' ~ 'responsibiliy' as well as 'Verantwortlichkeit' ~ 'accountability.'

Not sure correspondence is exact, in view of commenters involving culture traits such as "looking for scapegoats," @ShadowFox.

Divergent semantics evident from examples:

"Wer hatte hier die Verantwortung?" ~ "Who was in charge here?"

Try 'responsible,' doesn't seem to work very well.

Both words from the same root 'antwort,' simiilar to 'responsible.'

Neither word to be confused with 'Zurechnungsfähigkeit' ~ sanity *)

(=accountability under criminal law)?

– – –

*) Google translate

– – –

Difficult in German is J Lee's example, seems to reverse my above correspondence. Here my attempt at idiomatic German translation:

"[..] she was 'responsible' for a political climate conducive to violence […] anyone who said she must be 'held accountable' for the shooting [..]"

".. sie war für ein politisches, zu Gewalttätigkeiten geeignetes Klima verantwortlich .. wer sagte, dass sie zur Verantwrortung gezogen werden muss für die Schüsse .."

Here, the addition of "gezogen" seems to switch 'Verantwortung' to the 'accountability' meaning.

Am trying to learn, but sorry for meddling in linguistics, not my metier. Mein armes Affenhirn.

Nathan Myers said,

January 24, 2011 @ 12:14 am

I wonder if Guy Deutscher's approach may be applied here. Not having a word or contruct in the language doesn't mean it can't be understood, but maybe there are words denoting concepts that, in one culture, one cannot go without considering on a daily basis, that in another may never come to mind. In other words, not having the word doesn't handicap you, but having the word (inflection, grammatical construct, what have you) obliges you to make choices around it.

We might point out that while Swedes use cellphones more than Americans, perhaps only Americans need the expression "calling plan".

notrequired said,

January 24, 2011 @ 12:26 am

The notion that one must use the same number of words to translate a concept from L1 into L2 is ludicrous. It relies on a pointlessly strict definition of what it means to translate.

There is always some way to translate a concept, even if it takes an additional sentence. A skilled translator is able to solve the problem even if the target word/expression for a source concept does not appear to carry all the relevant connotations. Deciding what connotations are relevant in the context is a different matter. Not all connotations are relevant in every context, therefore one who searches for 'exact' matches that carry all connotations is on a fool's errand. A skilled translator is usually able to correctly understand what's relevant and what isn't (which may not always be easy).

To make a distinction between explanation and translation is, I think, also pointless, because the purpose of both is to convey a message to an audience.

And speaking of relevance, I suspect that chris is correct in his suspicion that the responsibility & accountability lecture was a perfect example of irrelevance. Either that or the translator did a poor job of explaining :)

Without being familiar with the content of the lecture (and assuming that there was indeed no way to render "responsibility" and "accountability" differently), the first idea that comes to my mind is a translation roughly like this: "I'd like to discuss two important kinds of X." X standing for responsibility/accountability in L2. And then the translation would simply go on by explaining the difference between the two kinds, as was presumably the lecturer's intent — to talk about two interrelated concepts. Doesn't really matter if you use the same word for both, as long as it is explained that a distinction is being drawn.

maidhc said,

January 24, 2011 @ 4:24 am

If I don't watch Italian TV, I have no need to know what a "veline" is. I sometimes watch Mexican TV, which frequently has scantily clad young women going hither and thither for no discernible purpose, so I have a concept of what that is, but whether the Mexicans have a word for them I don't know.

A lot of middle-aged British people, and very few others, would know what a "fotherington-tomas" is. There's no American equivalent to Canadian Tire. Most Swedes don't know what a pupusa is. The Russians have no word for Vegemite. Americans don't have a word for "blow-in".

Cultures are different around the world, and they all have words for things in their culture that don't translate into other cultures that don't have those things. Even within one country one can find micro-cultures that have a certain vocabulary that is not shared with the general population.

For example, for techies the words "parameter" and "glitch" have very specific and exact meanings. Yet those words have been adopted into the majority culture with very vague and, to the techie, nonsensical meanings.

I've been waiting for a while to bring this up, so maybe this is the time. Years ago, before the big server migration, there was a topic of "Irish has no word for sex". That was before I started reading this blog. When I read it, I thought it was totally wrong-headed, but it seems to have subsequently disappeared, so I don't have a chance to discuss it.

While we're on the subject of "Xish has no word for Y", could "Irish has no word for sex" be revived?

Emilio said,

January 24, 2011 @ 5:09 am

I won't even touch the general issues related to the "No word for X" cliché, since people like Pullum and Liberman have abundantly shown how misguided and silly the whole thing is.

Being Italian, I'll make a more specific point. The most straightforward way to settle the issue of translating "accountability" is to say that the concept is INCLUDED in the meaning of "responsabilità". Most Italian speaker will agree that, in its most general meaning, being "responsabile" for sth implies to face any legal or factual consequences of your actions. Actually I would say that this is by far the most common, every day use of the word. For sure, it's the first use children are exposed to.

It's true that Italian has only "responsabilità", while Engish as both "responsibility" and "accountability". But it cannot be mantained that "responsabilità" translates "responsibility" and there is no one-word translation for "accountability": it's just that the meaning of "responsabilità" is more comprehensive than that of "responsibility".

Moreover, as many others have already pointed out, the more specific concept expressed in English by "accountability" is easily translated by using the multi-word expression "rendere/dare conto di qualcosa a qualcuno".

ThomasM said,

January 24, 2011 @ 5:28 am

Good example, but I would say it wasn't even necessary to go to such lengths. To point out the absurdity of the idea that Italians have no word for, and thus no concept of, "accountability" in the sense of "being answerable", but have to make do with "responsibility", it would have been enough to mention that "responsibility" and its cognates in the various Romance languages actually contain the word "response", i.e.,"answer". To be sure, the etymology of words is not always a key to their current meaning(s), but in this case it certainly is.

PavleT said,

January 24, 2011 @ 6:00 am

The trophe was referenced by no less than the vice-president of the Italian Senate today, Emma Bonino (Italian Radical Party), in an English language interview on the UK's BBC Radio 4. She closed her interview saying, in reference to Berlusconi's recent scandals, "accountability doesn't even have an Italian translation" and went on to suggest a connection with the ease with which sins can be confessed in Catholicism.

army1987 said,

January 24, 2011 @ 6:05 am

How is gnéas not Irish for ‘sex’?

michael farris said,

January 24, 2011 @ 6:30 am

For the record, I'm all for tossing the "No word for X" meme into the trashcan of history. On the other hand, a lot of commenters here seem to be assuming some kind of universal semantic field (mostly based on English) where concepts X and Y always line up the way they do in English even if Y takes three words and X takes one.

Emilio brings up a very good point. Semantic fields line up differently in different languages and just 'translating' something with a different expression doesn't necessarily convey the same meaning.

In Polish the ideas of 'responsible' and 'accountable' (both normally translated with the same word) line up heavily with 'guilt/y' (which no one in Poland wants attached to them).

Does this mean people in Poland are irresponsible? Yes and no. Good behavior of the kind anglophones are liable to attribute to 'responsibility' will be attributed to something else in Polish, usually reliability, competence or conscientiousness.

Emilio said,

January 24, 2011 @ 6:46 am

@PavleT: This was to be expected. Italian Radicals have always been proudly Anglo-Americanophile. This doen't make the point more sensible.

Lameen said,

January 24, 2011 @ 7:12 am

This particular example looks bogus (we're supposed to believe that a speech community with the concepts of a Day of Judgment and of penance don't have a concept of accountability?) But as Michael Farris rightly notes, concepts line up differently in different languages. Moreover, the presence of a phenomenon in a given community (for example, anorexia, or zar) in some cases appears to be rather closely tied to the presence of a well-known concept of it – and if a concept is widely talked about in a community, there will almost certainly be a word or fixed expression for it in their language.

Frans said,

January 24, 2011 @ 7:37 am

Hermann Burchard

I'm not sure what you think is wrong with "who was responsible here," "who's responsible for this mess", "whose responsibility is this", etc.? Or do you just mean it's not a particularly good translation of the German sentence you wrote? What about a sentence like "Wer ist hier zuständig," which I've heard Germans say.

PS In Dutch it's aansprakelijk (accountable) and verantwoordelijk (responsible).

Colin Reid said,

January 24, 2011 @ 8:05 am

I suppose according to the 'no word for X' meme, a language such as German must cover an unusually rich conceptual landscape, given the potential complexity of compound nouns.

Rick S said,

January 24, 2011 @ 8:32 am

For the purpose of argument, let's grant that the oversimplified version of Whorfianism is obvious nonsense. I think there is still a case to be made for the hypothesis that it is more difficult to discuss accountability in French or Italian than in English.

All right, you can start a discussion in Italian by saying "rendere conto di qualcosa a qualcuno". From there you participate in an extended dialog on the topic of accountability with a partner. In this dialog you both need to refer to the concept a few dozen times. How do you do this?

Do you repeatedly use the phrase "rendere conto di qualcosa a qualcuno"? No, that violates the Maxim of Manner (avoid prolixity). Do you substitute a more inclusive brief term like "responsabilità"? Possibly, but that risks violating the same maxim (avoid ambiguity) and won't work at all if, as in brdo's aborted lecture, the topic requires a distinction between the two concepts.

The solution that works is to adopt, at least during this discussion, a brief term that the two of you mutually agree will represent the precise concept to be discussed. In other words, you coin a nonce "word for X" in Italian (e.g. rendizionia), or you borrow one from another language. Absent such a term, it's just too awkward to discuss clearly, or too ambiguous to discuss usefully. The discussion is syntactically possible, but pragmatically unlikely. In this sense, the "No Word For X" trope does have some meaningful application.

But, having said that, I would point out that even in English, any nontrivial discussion of X eventually requires isolating one or another specific concept from the semantic field denoted by X. In this sense, English has no word for [any of the several fine-grained concepts of interest being denoted by] "accountability". This simple fact alone exposes the fallacy of a stereotypical "No Word For X" claim.

Keith M Ellis said,

January 24, 2011 @ 9:13 am

Well, sure. But I don't think anyone is arguing otherwise.

What is being objected to, essentially, is the strong Worfianism implicit in the claim that because “accountability” doesn't translate exactly into Italian, then native speakers of that language, and the related greater culture, lack the idea of “accountability”.

Moreover, while I don't think anyone is arguing for a universal semantic field (I might or might not, though, if I knew what you meant by that), it does seem to me that the “no word for X” proponents are arguing for its inverse—that Italian qua Italian precludes in some sense an Italian word or phrase that is equivalent to “accountability”.

Put another way, there is a common notion that a given language has a particular character which is unique to it, and said “character” is both a kind of organizing principle and a constraint upon the language′s words and usages. This is another perspective on the same moderately strong Worfianism. It takes as its starting point the assumption that all words and usages in one language are necessarily semantically distinct from those of another. Not that they might be, but that they necessarily are.

I don't feel that I′m expressing this well. One thing that comes to mind that might get my point across is that it seems to me that the fact that English doesn't have a word for taking delight in the misfortune of others is exactly the same sort of thing as the fact that English doesn't have a word for something that is fourteenth from the end of an ordered list. Whether another language has words for these two things is irrelevant. English is equally capable of neologisms for those two concepts; and because both are relatively narrowly defined and, arguably, culturally independent, then there's little reason to assume that any other language's words for these two things wouldn't be virtually equivalent to English's.

The significance of whether a given language has a specific word for something, or that any two given languages have words that are very close yet distinct in meaning, is no greater nor lesser than those facts themselves. There is no magic line which unambiguously divides mutual comprehensibility from mutual incomprehensibility.

I suppose that I ought to revisit my copy of Le Ton Beau De Marot: In Praise Of The Music Of Language.

Emilio said,

January 24, 2011 @ 9:16 am

@Rick S: Your point is subtle and interesting, but it just doesn't apply to the case at hand. Let's take the verb "account for something" (discussing the pragmatic effectiveness of an abstract noun like "accountability" is hard in itself). Realistically, you should contrast the three-word expression "account for something" (noun + preposition + noun phrase) with the four-word expression "rendere conto di qualcosa" (verb + noun + preposition +noun), since the second argument "a qualcuno" can easily be dropped. It doesn't seem to make much difference in terms of conciseness. By the way, I've left in the argument prepositional phrase "di qualcosa" just for the sake of discussion: in most contexts you could drop that too, and you'll have the remarkably concise and elegant "rendere conto".

That's it. And as a reader of newspapers and political commentary I could testify that the expression does occur at times, also in connection with Berlusconi's scandals. So I'd dare to say that the point made by the NYT is rotten to the bone: Italian language DOES have an appropriate expression for the concept, and public debate in Italy actually deals with issues of accountability all the time. One can't do political analysis or cultural anthropology by resorting to dumb cocktail party pseudoscience.

brdo said,

January 24, 2011 @ 9:17 am

I asked this question in a previous thread on the same subject, but no one took it up. The topic was a report that people in a particular part of the UAE had "no word for snow". I pointed out that the language spoken by these same people has a common phrase, understood by everyone, which describes the praiseworthy act of killing a female relative that one suspects has been, voluntarily or not, in the presence of an unrelated man. How do you "translate" that into English?

Colin John said,

January 24, 2011 @ 9:43 am

There is a standard way of assigning roles within a piece of work in modern English business speak (both UK and US afaik). called a RACI analysis. The 'R' and 'A' here stand for Responsible and Accountable.

In this way of splitting roles the distinction is straightforward. The person or persons who actually have to do the work are 'Responsible'. The person (must be only one) who will get kicked if it doesn't happen, or doesn't work is 'Accountable'. This is marginally more prescriptive than everyday use and I wonder if this has influenced some of the discussion.

GeorgeW said,

January 24, 2011 @ 9:45 am

@brdo (January 24, 2011 @ 9:17 am): "How do you "translate" that into English?"

I think you just did.

Rick S said,

January 24, 2011 @ 10:02 am

@Emilio: I understand your argument, but in recasting it using the expression "account for something" you're now discussing a concept for which neither language has a "word", so it's hardly surprising that Gricean maxims wouldn't favor one over the other. The essence of my argument is that a brief conventionalized term is pragmatically necessary for intensive discussion of any concept, that lack of such a term might impede its discussion to some degree, but that notwithstanding these facts, the adoption of such a term in any given language is generally not difficult once the need for it is recognized. Where the "No Word For X" trope might find application is in suggesting that the need might not be recognized as readily in Language L, and indeed I could point to M. Girard's post as an example.

adriano said,

January 24, 2011 @ 10:04 am

The closest is “responsibilità” [sic] — responsibility — which lacks the concept that actions can carry consequences.

First: it's "responsabilità".

Second: responsabilità has precisley to do with actions which can carry consequences.

Mark F. said,

January 24, 2011 @ 10:25 am

When somebody says "Language X doesn't have a word for Y", you really don't know how strong a form of Whorfianism they're espousing. Yes, they may be thinking "The speakers of X have been so contaminated by their language that they simply cannot grok Y." Or, and I think more likely, they may be thinking "Speakers of X must not have done a lot of talking about Y or they'd have made up a word for it."

Dan T. said,

January 24, 2011 @ 11:37 am

@Rick S: It's a good point that it is in fact a common rhetorical device for somebody writing an essay introducing a novel concept (or one that is novel to the intended audience even if it may be more common in a different culture or subculture) to coin a temporary word for it, perhaps a compound word or one borrowed from a different language, for the purpose of discussion, defining it in the opening part of the essay. Sometimes such things might even catch on and become genuine English words, like "meme" (which, I believe, was introduced by Richard Dawkins).

Ben Hemmens said,

January 24, 2011 @ 12:02 pm

On Verantwortlichkeit and Verantwortung:

An interesting discussion on responsibility cropped up in the context of quality assurance in pharmaceutical manufacturing ("GMP"). The FDA's understanding of "the person responsible" is anyone who has "the power and the authority" to intervene in a process (e.g. to create an alert or initiate a corrective procedure). The whole purpose of this definition is to analyze responsibilities on the basis of the evidence about what happened in a particular situation and not only on the basis of who was responsible on paper. German speakers had trouble getting their heads around that. Responsibilities for them are formally assigned, they don't just arise spontaneously because of where you happened to be and what you saw.

Licia said,

January 24, 2011 @ 12:34 pm

It looks like there might be an Italian word for accountability after all!

I did a few quick searches which showed that in some political contexts rendicontazione politica is used, a calque of political accountability, and that rendicontazione sociale (social accountability) returns thousands of hits. I checked a few results and in most of them the distinction was made between responsabilità and rendicontazione, modelled on English accountability / responsibility (note, however, that rendicontazione sociale is also used to signify “social reporting”); rendicontazione morale and rendicontazione etica also occur.

I checked the latest editions of the main Italian dictionaries and I found that rendicontazione is only listed as “act of producing a financial statement” and marked as bureaucratese; the semantic neologism that conveys the “accountability” meaning is not yet recorded by any dictionary*. [Rendicontazione derives from rendiconto, a noun mainly used in financial contexts where it means “statement“ (of accounts, expenses etc.), but it can also describe a “detailed report” and, in some restricted contexts and only in its plural form, “report of proceedings”].

Moreover, rendicontazione sociale does not appear to be used consistently by all users. In a publication by the Italian government, Rendere conto ai cittadini. Il bilancio sociale nelle amministrazioni pubbliche, rendicontazione sociale is explained as a process that helps achieve accountability, e.g. see pages 20 and 21. Unfortunately there are no definitions and the explanations provided are not exactly crystal clear.

* Italian speakers might like to have a look at accountability, rendicontazione and responsabilità in Le cento parole della solidarietà, a glossary of nonprofit terminology extracted from the Devoto-Oli Italian dictionary.

peterm said,

January 24, 2011 @ 1:02 pm

For what it is worth, there has been some discussion within the philosophy of technology on different notions of responsibility. If intelligent software does not execute as intended, for example, just who, if anyone, is responsible, and precisely for what? As is often the case, a single word carries multiple and distinct meanings. See:

A. Kuflik [1999]: Computers in control: rational transfer of authority or irresponsible abdication of autonomy. Ethics and Information Technology,1 (3): 173-184.

Peter Taylor said,

January 24, 2011 @ 2:00 pm

@brdo, "honour" killing. The scare quotes are not obligatory. I don't know how widely it would be understood, but I think that in the UK, where newspapers use the term regularly, people would get the point.

Liz said,

January 24, 2011 @ 4:00 pm

Based on Licia's description here The word velina has quite a few connotations, the strongest of which is definitely "flimsiness"…

I think I might translate 'velina' as 'floozy' or 'tart' or 'bimbo'. Admittedly, the term looses its letter-turning context, but it seems to me that any of those terms would preserve the essential nature of these characters.

the other Mark P said,

January 24, 2011 @ 4:38 pm

Peter Taylor is correct that "honour killing" is the term.

New Zealand had its first such death only days ago (it seems, it's still a bit murky).

Yet somehow, despite the practice being totally foreign, we had already imported the term. Sufficiently that the news organisations use it without explanation.

(My personal "word" for veline is "those girls in ridiculously skimpy outfits on those ridiculous Italian TV shows", but "showgirl" would do in most circumstances.)

Mark said,

January 24, 2011 @ 5:14 pm

The best I can explain it to older folks on here, "veline" is the Italian word for Goldie Hawn on Laugh In. Though I suppose there may be a bit of Benny Hill in there as well.

:-)

Licia said,

January 24, 2011 @ 6:02 pm

@ Liz: veline might be scantily dressed, but they are not regarded as particularly vulgar, at least not in Italian eyes, so I don't think floozy or tart would be appropriate. And I am not too convinced about bimbo either because of the "stupidity" connotation – it's what they do that's totally idiotic, but not necessarily the veline themselves.

I would use the loanword velina also in English, like in the Wikipedia entry.

Nathan Myers said,

January 24, 2011 @ 10:52 pm

It's what they have been hired to do that is idiotic. Work is work, and sometimes you take what you can get. The person who hired them is the idiot.

maidhc said,

January 24, 2011 @ 10:58 pm

@army1987

There was a lot more to the discussion …

army1987 said,

January 25, 2011 @ 7:53 am

What? (The only relevant thing I find by Googling "no Irish word for sex" is an old Language Log post about a totally unsubstantiated passing remark by a novelist.)

un malpaso said,

January 25, 2011 @ 4:13 pm

Hey, I have an idea. Why not render "Velina" into English as "Vanna"? That is, as in Vanna White, as the original quotation referenced? There's a nice similarity of consonance there.

I wonder how many people still remember her, though, even here in the USA. :)

Andrew Bayles said,

January 25, 2011 @ 4:28 pm

The idea that having one word for a concept necessarily implies a better understanding of the concept is ridiculous. Just as the French have 'informatique' for 'computer technology', which might lead some to say that English has no word for 'informatique', you could say that English has no word for [insert any conjugated verb form from any of a number of different languages here].

For example, English has no word for the Arabic فَهِمتُماهُنا [fɐhɨm-tʊma:-hɨna:], which roughly translates as "They both understood the two girls."

Enlgish also has no word for such simple constructions as the Spanish "hablo" (I speak), which, although it may be preceded by the subject pronoun 'yo', need not be.

Similarly, I have had Spanish speakers ask me how we English-speakers tell who is being spoken two since there is only one 'you'. If we include direct- and indirect-object pronouns and all other direct equivalents of 'you', Spanish ranks in with fifteen or so:

tú, vosotros, usted, ustedes, vos

te, os, lo, la, le, los, las, les

ti, -tigo

Even fleshing out the English pronouns to include archaic and colloquial forms of 'you', we only manage about six:

thou, you, ye, you guys, y'all, yous guys, [and maybe] ya

So much for the one-for-a-concept-makes-a-language-better theory.

Hermann Burchard said,

January 25, 2011 @ 9:58 pm

@Frans: Wasn't thinking of a mess as you imply. My example ["Wer hatte hier die Verantwortung?" ~ "Who was in charge here?"] would apply to the case of commanding officer, now absent, being inquired about after an event, perhaps a combat scene with wounded removed, including whoever had been in charge, at fault or not. In such a very common situation a review would be in order, and certainly "who was in charge" would be the first question asked. — That's a longish reply, hope it helps.

John Ward said,

January 26, 2011 @ 1:06 pm

I may be missing the point here, but it seems like it's not 'accountability' but 'responsibility' that has no single word translation in Italian. People are getting confused by the etymology of the word.

'Accountability' is readily translated as 'responsabilita`', but 'responsibility' is (in English) a maddeningly elusive word to pin down. It's mostly used as part of idioms, where it means something sightly different in each one. It can be a good thing

For instance, to take responsibility for X means to be shamed, accept blame for Y. For X to be responsible for Y, means that X is the instigator or inciter of Y. To be 'responsible' point blank just means to be capable, mature, self-reliant, and resourceful.

It sounds like the speech wasn't well written, and it was difficult to translate because it was hairsplitting word-play to begin with.

Freddy Hill said,

January 26, 2011 @ 7:00 pm

"Rendir cuentas"

There's something I find interesting in that expression. Rendir means to surrender (and the fact that it's a "-ir" verb suggests that it's a very old verb. Modern Spanish only creates -ar verbs as neologisms – I'm told). So etymologically rendir cuentas means to "surrender your accounts."

I myself feel like I'm surrendering every April 15th

JR said,

January 27, 2011 @ 2:55 pm

Searching "veline" on YouTube makes it seem like it's some sort of television showgirl, perhaps analogous to a stereotypical scantily-clad weathergirl.

AP report on YouTube

Norms and attitudes around gender and broadcasting doesn't seem like a topic that would lend itself to perfect one-word translations in any culture where they vary.

John Cowan said,

January 29, 2011 @ 9:06 pm

Colin John's comment is the first thing that has made sense to me in this whole discussion, as it provides the critical information that accountability and responsibility are technical terms from a particular context. It's no surprise that random languages don't have specific technical terms (yet).

the semantics of ‘accountability’ (part 2) « Learning: Theory, Policy, Practice said,

September 19, 2011 @ 10:12 am

[…] always clear what people mean by it or what they think of when they hear or read it, not to mention translate it into another language. Yet it makes its way into policy papers, newspaper and radio reportage, and the titles and text of […]