Acquitted by heavy noun phrase shift?

« previous post | next post »

Tom Jackman, "Dropped 'at' in Va. law yields acquittal in school bus case", WaPo 11/30/2010:

Virginia law on passing a stopped school bus has been clear for 40 years. Here – read it yourself:

"A person is guilty of reckless driving who fails to stop, when approaching from any direction, any school bus which is stopped on any highway, private road or school driveway for the purpose of taking on or discharging children."

Yes, drivers must stop a school bus which is, er, stopped.

Wait. Is something missing there?

Indeed. The preposition "at" was deleted in 1970 when the law was amended, the statute's history shows. And a man who zipped past a school bus, while it was picking up children with its lights flashing and stop sign extended, was found not guilty recently by a Fairfax County Circuit Court judge.

"He can only be guilty if he failed to stop any school bus," Judge Marcus D. Williams said at the end of the brief trial of John G. Mendez, 45, of Woodbridge. "And there's no evidence he did."

A grammatical analysis offered by the defense persuaded the judge:

[Defense attorney Eric E.] Clingan then provided to [Judge Marcus D.] Williams a grammatical analysis by E. Shelley Reid, an associate professor of English at George Mason University. Reid noted that the phrase "when approaching from any direction" is a nonrestrictive modifier and can be removed from the sentence. "As a result," Reid wrote, "the grammatical core of the first half of the sentence would read, 'A person is guilty of reckless driving who fails to stop any school bus. . . . ' This is a cohesive, grammatically correct sentence that conveys a clear if not very reasonable meaning."

But Allen Browne, who sent me a link to the story, offered an alternative construal:

It appears to me that the problem is a confusing heavy NP shift. […] I think “A school bus” is supposed to be read as the direct object of “approaching”. Professor Reid thought that “School bus” was the object of “stop” because “when approaching from any direction” is an unrestrictive relative.

"Heavy noun phrase shift" refers to the fact that direct objects can be "shifted" so as to follow (rather than precede) other post-verbal material (in this case the prepositional phrase "from any direction") if the object is "heavy" enough. The wikipedia article uses this example:

1. (a) I gave the books which my uncle left to me as part of his inheritance to Bill

1. (b) I gave to Bill the books which my uncle left to me as part of his inheritance

The point is that "I gave to Bill the books" is at least odd if not ungrammatical, whereas a "heavier" direct object like "the books which my uncle left me as part of his inheritance" is fine in final position.

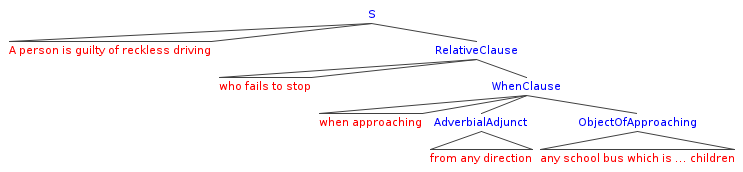

So Allen's analysis yields a tree with this general structure (click on the image for a larger version):

On this analysis, the only problem in the wording of the law (other than excessive structural complexity and consequent unclarity) is a couple of inappropriately-placed commas. Here's the sentence with the misleading commas removed:

A person is guilty of reckless driving who fails to stop when approaching from any direction any school bus which is stopped on any highway, private road or school driveway for the purpose of taking on or discharging children.

The prosecution, unfortunately, did not retain Allen as an expert witness, but rather fell back on a common-sensical argument about legislative intent:

[Assistant Commonwealth's Attorney Katie] Pavluchuk, who was simply handling the regular Thursday morning misdemeanor appeals docket, did not come prepared with case law and professorial analysis, as Clingan did. But her boss, Fairfax Commonwealth's Attorney Raymond F. Morrogh, was ready when asked about it this week.

"I respectfully disagree with the decision," Morrogh said. He cited a U.S. Supreme Court case from 1892 that said, "If a literal construction of the words of a statute be absurd, the act must be so construed as to avoid the absurdity."

He also said a full reading of the law makes its intention clear and pointed to a Virginia Supreme Court case that said that "the plain, obvious, and rational meaning of a statute is always to be preferred to any curious, narrow, or strained construction." The court also wrote, "We must assume the legislature did not intend to do a vain and useless thing."

And then the Fairfax prosecutor tossed in his own analysis of the Mendez case, through a Japanese proverb: "Only lawyers and painters can turn white to black."

As noted a few years ago. the validity of such arguments about intent is contested:

"Scalia on the meaning of meaning", 10/29/2005

"Is marriage similar or identical to itself?", 11/2/2005

"Legal meaning: the fine print", 11/2/2005

"A result that no sensible person could have intended", 12/8/2005

"Does marriage exist in Texas?", 11/19/2009

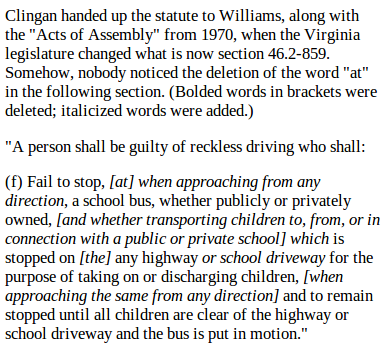

According to Jackman's WaPo story, the problem arose when the law in question was changed in 1970. His account, following that of the defense team, is that a crucial preposition was omitted. Unfortunately, the Post's description of the change seems to have been rather carelessly typeset:

There are no "bolded words in brackets", but if we interpret this to mean "italicized words in brackets", then we get this impossible-to-parse sequence as the original text:

A person shall be guilty of reckless driving who shall: (f) Fail to stop, at a school bus, whether publicly or privately owned, and whether transporting children to, from, or in connection with a public or private school is stopped on the any highway for the purpose of taking on or discharging children, when approaching the same from any direction and to remain stopped until all children are clear of the highway or school driveway and the bus is put in motion.

I could speculate as to how the reporter/editor/typesetter screwed up (for example, the which in "which is stopped" was presumably original), and try to reconstruct what the original text must have been, but I'd rather find the real historical version. Unfortunately a quick internet search didn't uncover it.

Whatever the history of the current wording, I found Allen's construal persuasive. On this account, the omission of "at" was not an error, but rather part of a re-parsing of the sentence. Anyhow, the state legislature can be apparently expected to amend the law during its next session, presumably so as to remove this problem without introducing any new ones.

kktkkr said,

December 1, 2010 @ 10:59 am

Even the version without commas is hard to read. Using "stop at" instead of "stop would solve the problem, but I'm not sure changing the word choice is the right solution here.

It's a really difficult crash blossom (thankfully without any crash).

[(myl) The wording of laws is not known for simplicity or clarity, to say the least. This is far from the worst example that we've discussed — consider for example the issues discussed here and here.]

Mr Fnortner said,

December 1, 2010 @ 11:31 am

Change "fails to stop" to "passes" and it becomes clear without "at". In fact, I thought "passes" might have been in the original, incorrected to "fails to stop" when the legislature strove for clarity, but that's not the case.

Scott Parker said,

December 1, 2010 @ 11:36 am

I think that moving the first comma from after "stop" to after "approaching" would solve the problem. The sentence would then become, "A person is guilty of reckless driving who fails to stop when approaching, from any direction, any school bus which is stopped on any highway, private road or school driveway for the purpose of taking on or discharging children."

John said,

December 1, 2010 @ 11:59 am

But if the judge accepted the grammatical claim, shouldn't he have found the defendant guilty for failing to stop the bus?

Thomas Thurman said,

December 1, 2010 @ 12:05 pm

John: How can you fail to do something you were neither trying to do nor had any duty to do?

anchorageite said,

December 1, 2010 @ 12:23 pm

Thomas: But he did have a duty to stop the bus. It's right there in the statute.

UK lawyer said,

December 1, 2010 @ 12:24 pm

This type of American law features in Hollywood films but is unknown in the UK (at least to me). We do, however, seem to have imported large numbers of the famous US yellow school bus in recent years.

I am curious as to how long the stopping must last – is it for a millisecond or as long as the bus is stopped? This is not explained in the wording.

As for the drafting, it is clearly dreadful and needs surgery. Arguably a defendant should only suffer criminal penalties if the legal obligation is clear, so I have some sympathy with the judge. In the UK, "Mr Loophole" has made a good living getting celebrities off speeding charges on technicalities.

Sarah D said,

December 1, 2010 @ 12:58 pm

UK Lawyer- I live very close to Fairfax, VA. School buses have a blinking stop sign on the side that folds in and out, kind of like the barriers at railroad crossings. The driver activates it when stopping to let children off. You have to stop and wait until the driver turns it off and folds it back in. It's a very well-known law and I'm shocked that it's worded so badly in the books. Bus drivers often take down the license numbers of drivers who fail to stop.

MattF said,

December 1, 2010 @ 12:58 pm

@UK lawyer

Well, normally a stopped school bus in my neighborhood will have stop signs sticking out of its sides and red lights flashing all over– the message that drivers should not pass is not subtle or subject to a lot of different interpretations. When the stop signs retract, and the red lights stop flashing, and the bus starts moving again– it's probably OK to take your foot off the brakes.

Neal Goldfarb said,

December 1, 2010 @ 1:02 pm

The defendant's analysis strikes me as dubious.

In order to interpret the statute as prohibiting failure to stop a school bus, it's necessary to interpret stop as transitive, with any school bus being its direct object. But on that interpretation, it's not at all clear to me think that any school bus is available to serve as the direct object of approaching in when approaching from any direction. If it's not, the phrase when approaching from any direction is semantically incomplete: approaching what from any direction?

Alan Gunn said,

December 1, 2010 @ 1:02 pm

I once had a student who had a mental condition that made him insist on literal readings of everything he saw. It was remarkably interesting. The plainest statutes (well, plain by tax standards anyway) turned out to be meaningless or downright crazy when looked at closely enough. If everyone read things that way all sorts of ordinary communication would break down, because it's not practical to engage in the sort of drafting needed to avoid absurd, literal meanings. Words should be read on the assumption that the writer or speaker had in mind some reasonably sensible goal. Everybody understands what people mean by "I could care less," the same sort of understanding should apply to legislation, too.

There are quite a few legal scholars who insist that literal readings of legislation, without reference to the purposes underlying that legislation, is desirable. These people are almost all lawyers who do not, in their own work, read statutes carefully and who do not practice in areas (tax, commercial law, etc.) in which long, intricate statutes play an important role. Many of them seem to be pining for the good old days of the common law and looking for a way to deal with all those pesky statutes without having to learn what they are about.

Every American driver should know how to behave in the presence of a stopped school bus (the big red "STOP" sign is a clue), and only an idiot could fail to understand what the Virginia legislature had in mind.

[(myl) Though I'm sympathetic to the idea that statutory interpretation should (and even must) take account of what the drafter must have meant (or not meant), at least in obvious cases, this is (I think) an example where a sensible literal meaning is in fact available.]

Sid Smith said,

December 1, 2010 @ 1:11 pm

"A person is guilty of reckless driving who fails to stop, when approaching from any direction, any school bus which is stopped…"

Pretty mean to ask a driver to stop a bus which is already stopped.

Neal Goldfarb said,

December 1, 2010 @ 1:17 pm

Speaking of NP shift in legalese, this is the language that is used in federal indictments charging possession of drugs with intent to distribute them:

GeorgeW said,

December 1, 2010 @ 1:49 pm

@Alan Gunn: I agree. Although poorly worded and literally incorrect, the meaning was clear to me. I doubt very seriously that the driver's failure to stop was based on a literal reading and misunderstanding of the statute.

I wonder what was written in the Virginia driver's handbook. I have never read my state's driving statutes but, I have read the driver handbook.

Army1987 said,

December 1, 2010 @ 2:27 pm

Unless commas are added or removed, I can't see any other possible literal interpretation than Prof. Reid's.

Glenn said,

December 1, 2010 @ 2:30 pm

A truly ridiculous ruling by the judge. I realize that the TV version of the legal process leads people to think that the law operates in this sort of "gotcha!" fashion, but it's really not true. Reasonableness, and not pedantic absurdity, is actually the governing principle in statutory construction.

davep said,

December 1, 2010 @ 3:31 pm

UK lawyer said: "to how long the stopping must last – is it for a millisecond or as long as the bus is stopped? This is not explained in the wording."

Well, if you start moving while the bus is stopped, you aren't stopping. That is, the only reasonable interpretation is that, if the bus is stopped, you must stop (if moving) and stay stopped (until the bus is no longer stopped).

Geoffrey K. Pullum said,

December 1, 2010 @ 4:52 pm

Actually, no one has put their finger on the true grammatical disaster here: it's the second comma. Things would get a little clearer if the truly optional part, "from any direction", were parenthesized. Then you'd have this:

When you're approaching a school bus, you have to stop. It's as simple as that. But since a comma between verb and direct object is ungrammatical in English (unless there's some other motivation for the comma), the statute is ungrammatically phrased. Still, never mind, the Supreme Court opinion from 1892 stands: you have to take the sensible interpretation (the one I've just given) over the stupid one. The Supreme Court will have to take this on and reinstate Mr. Mendez's fine, I'm afraid.

Nick Z said,

December 1, 2010 @ 5:53 pm

@davep: when you come to a 'stop' sign at a junction you don't have to stay stopped until the sign goes away. You stop, and then you can start again. So UK lawyer's question is not unreasonable.

Lemmethink said,

December 1, 2010 @ 6:33 pm

How unbelievably ridiculous!

"'He can only be guilty if he failed to stop any school bus,' Judge Marcus D. Williams said at the end of the brief trial of John G. Mendez, 45, of Woodbridge. 'And there's no evidence he did.'"

So, everybody is under an obligation to stop a school bus. If you see a school bus and do not stop it, you're infringing the law.

So, nobody has got a right to drive a school bus: he MUST be stopped. And the children must go to school on foot!

In America, at least.

"Purus grammaticus, purus asinus."

Rubrick said,

December 1, 2010 @ 6:49 pm

When in high school, in Drivers' Ed., we learned that by Ohio law, in order for a vehicle to be legally classified as a school bus, it must have the words "SCHOOL BUS" on both the front and back.

On a quiz, we were given the following question: "You are driving on a two-lane road. In the other lane is a yellow bus, stopped, with the words "SCHOOL BUS" painted on the front. Are you required to stop for the bus?"

I answered No, on the grounds that it was unknown whether it also had "SCHOOL BUS" on the back; if not, it wasn't legally a school bus and I was not required to stop.

Remarkably, I wasn't just being a smartass; I actually thought I had correctly answered quite a devlish trick question, and was outraged that the teacher marked my answer as wrong.

Ian Preston said,

December 1, 2010 @ 7:19 pm

You can piece together original text (or at least that in the Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia of 1968) from overlapping fragments accessible through Google Books. It seems to have said: "(f) Fail to stop at a school bus whether publicly or privately owned and whether transporting children to, from, or in connection with a public or private school stopped on a highway for the purpose of taking on or discharging school children, when approaching the same from any direction and to remain stopped until all school children are clear of the highway and the bus is put in motion, or fail to stop at a school bus, whether publicly or privately owned and whether transporting children to, from, or in connection with a public or private school, stopped on the roadway of a school for the purpose of taking on or discharging school children, when approaching the same from any direction on the roadway of such school and to remain stopped until all school children are clear of the roadway, provided, however, that this shall apply only to school buses which are painted yellow with the words "School Bus, Stop, State Law" printed in black letters six inches high on the front and rear thereof." So it's not that "which" was in the original version but that both "which" and "is"were missing.

J. Goard said,

December 1, 2010 @ 8:25 pm

@Neal Goldfarb:

But surely approach can be used intransitively, with the sense of 'approaching the relevant scene'?

John said,

December 1, 2010 @ 9:30 pm

Are you sure it wasn't:

…fail to stop [at], when approaching from any direction,…

Commas seemingly bear much legal weight now.

What would Jane do?

Neal Goldfarb said,

December 1, 2010 @ 10:16 pm

@J. Goard:

Yes, it can be intransitive syntactically (meaning that it has no overt direct object) but not semantically (meaning that the location that is being approached has to be identifiable from the context).

When I questioned whether any school bus… was available as the direct object of approaching, I was speaking in terms of semantics as well as syntax, although I didn't make that very clear.

Melissa Peskin said,

December 1, 2010 @ 11:31 pm

Yet another embarrassing day to be a Virginian…if it's not our wacky attorney general or our anti-tolerance holiday renamings, it's our poorly punctuating legislators. To me the worst part is how triumphant the scofflaw is. And I don't see how that text can be the entire law, because I believe it doesn't apply across a divided highway (and I think they explain that detail on the news every September).

Thanks for bringing some sense to the matter.

maidhc said,

December 2, 2010 @ 4:38 am

I believe Melissa is correct that the law is incomplete. Similarly, you are not required to pull over if an emergency vehicle with lights and siren is on the other side of a divided highway.

Every day when I go to work, I make a left turn across a double yellow line into the parking garage. I went to the trouble of researching the law. It is legal to make a left turn across a double yellow line to enter a private driveway. But if the two yellow lines are more than a certain distance apart (I think it's three feet), it's not legal to cross it. However, where I make my left turn, one of the two yellow lines is on a diagonal that ends up quite a distance away from the other. My trajectory on making the turn goes through the middle of the diagonal part, so while it might be three feet apart for the right front wheel, it would only be 18 inches apart for the left wheel.

I've been doing this for 15 years and have never got a ticket, but if I ever do, I'm going to argue it through.

John said,

December 2, 2010 @ 10:08 am

I think Scott Parker and Geoffrey Pullum have got it. It's meant to be intransitive 'stop', not transitive 'stop … any bus', so the comma should be moved from after 'stop' to after 'approaching'.

"A person is guilty of reckless driving who fails to stop, when approaching from any direction, any school bus which is stopped on any highway, private road or school driveway for the purpose of taking on or discharging children."

-> Parsed as is, this can only mean "stop any bus" with the "when approaching…" part as a parenthetical. It's also rather clumsily worded, which should be a hint to it's being mispunctuated – if the bus is an argument of "stop", then what is the car approaching? Unlike 'stop', 'approach' doesn't make a lot of sense as an intransitive.

"A person is guilty of reckless driving who fails to stop when approaching, from any direction, any school bus which is stopped on any highway, private road or school driveway for the purpose of taking on or discharging children."

-> This can only mean "stop when approaching any bus".

Of course, the bigger issue is that courts can be convinced to put literal grammatical interpretation over sensible semantic interpretation.

Ellen K. said,

December 2, 2010 @ 1:53 pm

I've no trouble with "any school bus" as the direct object (or semantic equivalent) of both "stop" and "approaching". Approach does work just fine intransitively, as long as the what's being approached is understood. Here, as I read it, what one is approaching is the bus that one is failing to stop. A perfectly sensible way to write about failing to stop a school bus that one is approaching, if one were to want to write about that. Well, until we get to the part where this only applies to stopped school buses. :) It doesn't strike me as at all clumsily worded if understood as talking about stopping a stopped bus. Nonsensical, yes, but not clumsy.

Clayton Burns said,

December 2, 2010 @ 2:28 pm

The Washington Post has made a mess of this story. Carelessly, the reporter truncated the section, if the material I have here is accurate (I have split it into separate numbered sentences to make it easier to follow).

The judge's ruling (as Geoffrey Pullum points out) is unsound. It is fantastical nonsense. It is amazing that an associate professor of English could have come up with such a ridiculous analysis. In sense making, we piece together semantic and contextual clues to produce reasonable interpretations.

What is clear is that the brand of English being taught in law schools is arbitrary and silly. Why these schools can't make the COBUILD English Grammar and corpus dictionaries official is a mystery. At a recent criminal trial I attended, the jury asked a question about "procure" in relation to materials that ended up being used in the Air India bomb. This is room service with the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English or the COBUILD dictionaries. You compare them with American products to get a sensitive reading. The judge dragged out an old Oxford and misled the jury.

By radically truncating the first sentence and deleting the context of my numbered sentence 2., the reporter presented a totally misleading picture. This sentence 2. completely obliterates any fussy and hysterical readings of grammatical ambiguity.

[2006 Virginia Code § 46.2-859 – Passing a stopped school bus; prima facie evidence

1.A person is guilty of reckless driving who fails to stop, when approaching from any direction, any school bus which is stopped on any highway, private road or school driveway for the purpose of taking on or discharging children, the elderly, or mentally or physically handicapped persons, and to remain stopped until all the persons are clear of the highway, private road or school driveway and the bus is put in motion.

2.The driver of a vehicle, however, need not stop when approaching a school bus if the school bus is stopped on the other roadway of a divided highway, on an access road, or on a driveway when the other roadway, access road, or driveway is separated from the roadway on which he is driving by a physical barrier or an unpaved area.

3.The driver of a vehicle also need not stop when approaching a school bus which is loading or discharging passengers from or onto property immediately adjacent to a school if the driver is directed by a law-enforcement officer or other duly authorized uniformed school crossing guard to pass the school bus.]

Clayton Burns said,

December 2, 2010 @ 4:55 pm

It is certain that the best teaching grammar for prospective law students and for law schools would be the COBUILD English Grammar, with the COBUILD Intermediate English Grammar as the beginners' text.

However, I have great respect for Geoffrey Pullum, and his "The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language" should be the official reference text for law schools and courts in America. (The two COBUILD grammars could also be consulted for this purpose).

John Sinclair told me that he was unhappy with the American uptake of COBUILD. The failure of what should be such a language-sensitive discipline as law to adopt the best tools of Linguistics in an integrated way is a disgrace. A true index to the incompetence is the above decision.

If any school children die as a result, the state and others involved should have to pay heavily. It should be a lesson to academics not to offer factitious analysis when given the opportunity to be expert witnesses.

I have The Official LSAT PrepTest 60, June 2010 from the Law School Admission Council, Inc., 662 Penn Street, Newtown, PA. Now, what would work better? Repeated study of "A Civil Action" (a good source of sound grammar), the COBUILD English Grammar, and the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (with its excellent CD) as the curriculum for law school admissions tests, or LSAT manuals? UPenn could get federal funding to examine LSAT minutely, given that Newtown is so close. A comprehensive analysis of the linguistic skills needed by lawyers and judges would show that the LSAT is an anachronism.

One of the best ways to become familiar with grammar is to assimilate the patterns in corpus dictionaries. (It is easy to link the COBUILD English Grammar, chapter 9, with the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English by looking up COBUILD's listed reference nouns in LDOCE. If judges were more sensitive to abstraction, their rulings might be more accurate.

Spell Me Jeff said,

December 2, 2010 @ 4:57 pm

More context for anyone who cares. Following the citation for the VA code, I read the statute, and, getting curious, read a bunch of related statutes. Many, though not all, make specific reference to the fact that the person in violation of the statute is actually driving a motor vehicle. This statute (859) would be a touch clearer if the word "stop" were indeed transitive, and the direct object were in fact the driver's own vehicle. Of course, this would require more significant editing. Still . . .

Spell Me Jeff said,

December 2, 2010 @ 5:01 pm

Oh, but I do agree with Clayton Burns that the rest of the statute makes 859 virtually impossible to misconstrue, despite that rascally comma.

John G said,

December 2, 2010 @ 8:55 pm

If I were the prosecutor, I would be strongly urging an appeal. Besides the free-standing absurdity of the trial judge's reasoning, Clayton Burns's argument from context is persuasive. Also, if the trial decision stands, no one approaching a school bus (from either direction) in Virginia needs to stop, until the legislature gets around to amending the statute.

One of the challenges of interpreting much US legislation is that not all states have professional drafters; the statutes may be drafted by the legislators themselves, who have uneven talents for that activity.

Here's what the Highway Traffic Act of Ontario says about the topic:

Duty of drivers when school bus stopped

s. 175(11) Every driver or street car operator, when meeting on a highway, other than a highway with a median strip, a stopped school bus that has its overhead red signal-lights flashing, shall stop before reaching the bus and shall not proceed until the bus moves or the overhead red signal-lights have stopped flashing.

s. 175(12) deals with approaching such a school bus from the rear and requires the driver to stop at least 20 metres behind it for the same period.

Pretty clear, because drafted by professional (and IMHO very competent) drafters.

.

John G said,

December 2, 2010 @ 9:00 pm

Rubrick's question points to a different issue in legal drafting: definitions should not be mixed in with substantive rules. It may be a requirement that a school bus must have 'school bus' painted on the front and the back, but the presence of those words should not be part of the definition of a school bus. Otherwise failure to meet a minor rule like this could put people in serious danger – or make literal-minded compliance difficult because, as Rubrick pointed out, it is hard to know when approaching a bus (from either direction) whether it has the words painted on both ends.

Melissa Peskin said,

December 2, 2010 @ 10:44 pm

I like John G's point about professional drafters. Virginia prides itself on "citizen legislators" but we would definitely benefit from a consultant to the legislature who has studied both law and linguistics.

dwmacg said,

December 3, 2010 @ 8:53 am

The words in brackets were bolded in the print edition, but that got changed to italics in the online edition. But of course no one bothered to make the appropriate edit.

Tim Macdonald said,

December 4, 2010 @ 8:02 pm

There are two competing presumptions here. The first is that you should prefer a sensible interpretation over a silly one. But the second is that where there is any ambiguity in a criminal statute, you interpret it in favour of the defendant. This is part and parcel of the all-important presumption of innocence.

For example, in the English case of Hobson v Gledhill [1978] 1 WLR 215, the court had to interpret section 1(1) of the Guard Dogs Act 1975, which says:

“A person shall not use or permit the use of a guard dog at any premises unless a person (‘the handler’) who is capable of controlling the dog is present on the premises and the dog is under the control of the handler at all times while it is being so used except while it is secured so that it is not at liberty to go freely about the premises.”

Dogs were left on a long chain with no handler present. Had an offence been committed? The question was whether "except" had scope over the whole paragraph, or only over the latter part (from "and the dog" to "so used"). The court decided that, as this was a penal statute, any ambiguity had to be construed in favour of the defendant, even if their initial impression was for the other reading.

Now, in my opinion the pro-defendant reading in the Virginia school bus case is so silly that it is strong enough to overcome the presumption in favour of the defendant. I'm not even convinced it's in any way tenable – if it isn't, there's no ambiguity at all. But I have to recognise that the presumption of innocence is (and must be) very strong, so it's not a completely insane decision. If the State wants to make sure it can convict people, it should put its commas in the right place.

PeterW said,

December 5, 2010 @ 12:58 am

The defendant should have been acquitted.

1. The first reason is, as Tim notes, the rule of lenity, which provides that any ambiguity in a criminal statute is construed in favor of the defendant. This is based on the reasonable idea that if someone can be imprisoned for breaking a law, the state has an obligation to make the law clear.

2. The second reason is that the evidence presented to the trial judge showed that the defendant didn't commit the offense. The defense presented expert testimony from a linguistics professor explaining what the statute actually said. The state countered with the argument that, well, we all know what the legislature meant. Even though the prof may well have been wrong in her interpretation, the state failed to present any *evidence* supporting an alternative interpretation.

3. Every state now has professional drafters. And proofreaders and editors. But things were a lot different even 40 years ago, when this statute was last touched. (Note, too, that you can't just send someone in to clean up poorly written laws; you have to first fix it, and then, like any other law, it has to pass both houses and be signed by the governor.)

Aaron Davies said,

December 5, 2010 @ 1:22 am

nice subjunctive btw in the supreme court quote on construction principles

Clayton Burns said,

December 5, 2010 @ 4:11 pm

PeterW: You write: "The defense presented expert testimony from a linguistics professor explaining what the statute actually said." That is a distortion. Did the "linguistics professor" appear as an expert witness? Was she cross-examined? Your linguistics professor is a composition professor at George Mason, where Linguistics is appended to the English department.

I would not consider a composition professor where such classics as D. Hacker's "A Writer's Reference" are thought worth teaching to be a promising expert witness in a case of this nature. I wonder if E. Shelley Reid discussed her opinion with Steven Weinberger, Director Linguistics, George Mason?

We have an informal if not off-the-wall opinion that could expose George Mason to trouble if any school children were to die as a result of this irrational ruling. As far as drafting goes, you are going in circles. The case reveals the need to adopt the right linguistic tools, as outlined above. The "state" could have made powerful arguments if it had had the linguistic awareness. The ambiguity in Hobson v Gledhill is not even remotely of the nature of any ambiguity that might be seen in Mendez. Dogs, a handler, or no handler. A driver, a school bus:

–Clingan then provided to Williams a grammatical analysis by E. Shelley Reid, an associate professor of English at George Mason University. Reid noted that the phrase "when approaching from any direction" is a nonrestrictive modifier and can be removed from the sentence. "As a result," Reid wrote, "the grammatical core of the first half of the sentence would read, 'A person is guilty of reckless driving who fails to stop any school bus. . . . ' This is a cohesive, grammatically correct sentence that conveys a clear if not very reasonable meaning."–

Gordon P. Hemsley said,

December 27, 2010 @ 2:13 am

Am I the only one who has a problem with the construction "A person is X who Ys"? Or is that in itself a heavy VP/CP shift from "A person who Ys is X"?