Two cultures

« previous post | next post »

Many years ago, as a grad student attending an LSA summer institute, I took a course from Harvey Sacks and Emanuel Schegloff based on their work with Gail Jefferson, published as "A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking in conversation", Language 1974. That paper's abstract:

The organization of taking turns to talk is fundamental to conversation, as well as to other speech-exchange systems. A model for the turn-taking organization for conversation is proposed, and is examined for its compatibility with a list of grossly observable facts about conversation. The results of the examination suggest that, at least, a model for turn-taking in conversation will be characterized as locally-managed, party-administered, interactionally controlled, and sensitive to recipient design. Several general consequences of the model are explicated, and contrasts are sketched with turn-taking organizations for other speech-exchange systems.

At the recent IEEE ICASSP meeting in Dallas, one of the papers that caught my eye was Chi-Chun Lee and Shrikanth Narayanan, "Predicting interruptions in dyadic interactions", ICASSP 2010. Their paper starts like this:

During dyadic spontaneous human conversation, interruptions occur frequently and often correspond to breaks in the information flow between conversation partners. Accurately predicting such dialog events not only provides insights into the modeling of human interactions and conversational turntaking behaviors but can also be used as an essential module in the design of natural human-machine interface. Further, we can capture information such as the likely interruption conditions and interrupter’s signallings by incorporating both conversation agents in the prediction model (we define in this paper the interrupter as the person who takes over the speaking turn and the interruptee as the person who yields the turn). This modeling is predicated on the knowledge that conversation flow is the result of the interplay between interlocutor behaviors. The proposed prediction incorporates cues from both speakers to obtain improved prediction accuracy.

This work comes out of Shrikanth Narayanan's SAIL ("Signal Analysis and Interpretation Laboratory") at USC, where a lot of interesting work is done. But before going on to tell you a little more about this work on interruption-prediction, I want to note the curious lack of communication between the disciplinary configurations represented by these two quoted passages.

Reading the two passages, an outsider might think that the researchers responsible for them were working on the same range of problems, and even in the same general disciplinary tradition, modulo the changes to be expected over a timespan of 35 years. But in fact, they come from two radically different traditions, which may or may not be mutually intelligible, but in any case are almost entirely without any direct communication.

Manny Schegloff is still an active researcher, in the sociology department at UCLA, roughly ten miles away from USC. I suppose that Schegloff and Narayanan must know of one another's existence. However, in documents on SAIL's website, Schegloff is never cited or mentioned. (This is not an indexing problem, since e.g. Liz Shriberg is cited 49 times, as well she should be. ) And the lack of communication is apparently mutual — Narayanan is apparently not mentioned in any of Schegloff's publications.

I wouldn't normally comment on this sort of thing, but I couldn't quite resist the irony of two researchers working on communicative interaction, at institutions less than ten miles apart, without any communicative interaction. Still, I should make it clear that this is not a matter of personal relationships, as far as I know, but rather the typical circumstance of disciplinary isolation. The world of speech and language research could be described as a sort of intellectual Balkans, except that the norm is not so much mutual hatred as mutual ignorance. There are at least half a dozen major cultures, and dozens more minor ones, all living and working more or less as if they were separated by impassable mountains and unfordable rivers.

OK, back to Lee and Narayanan's interesting work on interruption:

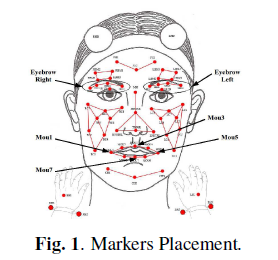

We used the IEMOCAP database for the present study. It was collected for the purpose of studying different modalities in expressive spoken dialog interaction. The database was recorded in five dyadic sessions, and each session consists of a different pair of male and female actors both acting out scripted plays and engaging in spontaneous dialogs in hypothetical real-life scenarios. In this paper, we are interested in the spontaneous portions of the database since they closely resemble real-life conversation. During each spontaneous dialog, 61 markers (two on the head, 53 on the face, and three on each hand) were attached to one of the interlocutors to record (x, y, z) positions of each marker.

Here's what the marker positions were like:

The basis of the study was a comparison of 130 interruptions and 252 "smooth transitions": In total, we annotated 1763 turn transitions in which 1558 were smooth transitions and 215 were interruptions. Since the distribution of these two types of turn transitions is highly unequal, we downsampled the data by including only three sessions (six subjects) of the IEMOCAP database with three dialogs chosen for each recording session. Subjects and dialogs were selected to include a majority of the annotated interruptions. In total, there are 382 turn transitions annotated with 130 interruptions and 252 smooth transitions used as our dataset in this paper.

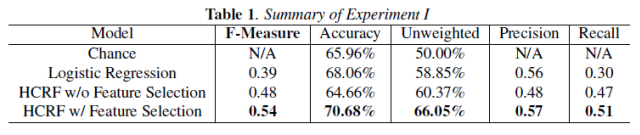

Thus in classifying transitions as "interruption" or "smooth", the baseline performance is what you get by always guessing "smooth", namely 252/382 = 66%. Using the face and body-gesture features of the interrupte, and various acoustic features of the interruptee, both taken during a one-second period prior to the transition, Lee and Narayanan were able to do a bit better than this:

Logistic regression got them to 68%, and a "hidden conditional random field" model, with some special attention to feature selection, got them nearly to 71%. (The "Precision" and "Recall" values mean that in their best-performing model, 57% of the transitions predicted to be interruptions actually were interruptions, while 51% of the interruptions were predicted to be such. And they used a cross-validation approach, so that the numbers are not inflated by testing on the training set.)

The most striking fact about this result, it seems to me, is that interruptions turn out to be so hard to predict, at least in this particular collection of interactions. I wouldn't have predicted that.

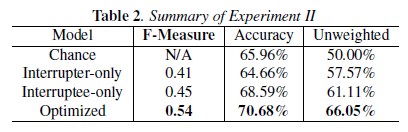

They also tried predictions based only on one side or the other of the interaction. Here again, the results are a bit surprising:

In other words, when they try to predict interruptions solely from the interrupter's face and body kinematics, they do a bit worse than chance. Predicting solely on the basis of the interruptee's audio features, they do somewhat better.

[Note to self: someday post about the relationship of this work to Yuan, Liberman & Cieri, "Towards an integrated understanding of speech overlaps in conversation", ICPhS 2007.]

Dan T. said,

March 20, 2010 @ 10:32 am

Does this research suggest any strategy to manage to get a word in edgewise when there are two other people in the room who don't seem to want to give you a chance to speak?

John Cowan said,

March 20, 2010 @ 1:06 pm

Pounding the table and bellowing generally works for me.

MikeM said,

March 20, 2010 @ 3:47 pm

Re Dan T's comment: just visualize "getting a word in edgewise!"

D.O. said,

March 20, 2010 @ 6:07 pm

Correct me if i'm wrong, but it seems that they selected dialogs, where ratios of interruption/smooth transition were more to their liking (that is more equitable). But that alone could bias the sample toward interruptions looking more like smooth transitions. For example, people ,ight be more willing to interrupt if it does not look like real interruption.

Christian DiCanio said,

March 20, 2010 @ 7:53 pm

Years ago, as an undergraduate, I worked on combining Schegloff's work on interruptions in conversation with Pierrehumbert's work on intonation. I wrote my undergraduate thesis trying to answer the question of what cues people use in order to decide to finish another person's sentence. I was also interested in whether or not people "finish other people's intonation" along with any sort of grammatical structure.

As an undergraduate, my work was not too rigorous, but I collected about 200 interruptions from dyads where each person knew the other person well. Of these, a small subset (I think it was about 20) were unambiguous cases of "finishing the person's sentence." Following Schegloff and Pierrehumbert, I found that people normally could finish another person's sentence only after a nuclear pitch accent had occurred (and, in particular, only during final, more predictable phrasal accents). My intuition at the time was that interruptions like these are less likely to be considered infelicitous because of where they occur in the intonational structure.

While I haven't worked on this topic since then, I did learn something through this process: One could make substantial progress within the research area of interruptions simply by combining knowledge of linguistic patterns/theory with Schegloff's work. Perhaps the lack of success in determining interruptions in Narayanan's work could be improved by considering the work on intonational phonology along with Schegloff's work.

Dan T. said,

March 20, 2010 @ 9:58 pm

I've always imagined that if I had Green Lantern's power ring from the comic books, I'd use it to project a "Word-In-Edgewise Scalpel" to force myself into any conversation I wanted.

Dan S said,

March 21, 2010 @ 12:12 am

Are "precision" and "recall" standard terms of their art?

[(myl) Yes.]

How are these different from "specificity" and "sensitivity".

[(myl) My understanding is that precision and recall originated in document retrieval, and sensitivity and specificity originated in biomedical testing. These days, the precision/recall terminology remains commoner in linguistic classification tasks.]

J.B. said,

March 23, 2010 @ 11:43 am

Recall is the same thing as sensitivity:

precision = (true positives) / (true positives + false positives)

recall = (true positives) / (true positives + false negatives)

sensitivity = (true positives) / (true positives + false negatives)

specificity = (true negatives) / (true negatives + false positives)

Robert said,

March 23, 2010 @ 9:27 pm

On two distinct occasions I've met people where it's hard to interrupt them while you're the only person they're talking to.

Chi-Chun (Jeremy) Lee said,

March 24, 2010 @ 6:30 pm

Thanks for pointing out some of the future direction and useful comments and references to look for this work. I believe that much work can be done by including the usage of lexical features, dialog acts, even affective state as one more level of features. I also did a paper in Interspeech08 on analyzing multimodal cues of different types of overlapping talks (disruptive/cooperative). This work tries to extend that by doing prediction, and yeah many difficulties has come because of vast speaker variation, and many context dependent situation.

Chi-Chun (Jeremy) Lee said,

March 26, 2010 @ 5:19 pm

P.S. If people are interested in this motion capture database. The SAIL IEMOCAP database is an actor-based (10) dyadic interaction database design to study multimodal expressive human communication. It utilizes motion capture technology to capture detail facial expression

along with the HD video/audio. The database is transcribed and annotated with emotion labels. In fact, there is more information about the database on sail.usc.edu/iemocap. In fact, we are releasing part of the database. Please feel free to contact me (chiclee@usc.edu) or Angeliki (metallin@usc.edu) if you are interested it.

Herb Isenberg said,

March 28, 2010 @ 2:29 am

Interruptions are a context sensitive phenomenon; what may be an interruption in one social setting or culture, may not in another. What is the definition of interruption? What can we learn from them. Note: I have a patent pending: Natural Conversational Technology and Methods, in part based on Harvey Sacks works. It works independent of culture, gender or age, and can "layer" interruptions appropriately, and even predict the likelihood of their occurrence based on turn taking patterns. If your interested, I am happy to share this new analytical paradigm with you.