Color vocabulary and pre-attentive color perception

« previous post | next post »

Do the well-demonstrated Whorfian effects in color discrimination really reach down to the level of perception? Some recent research suggests that Whorfian effects may exist at a level that is literally perceptual.

The term "Categorical Perception" (CP) names people's propensity to make finer discriminations at the boundaries between categories than at their interiors. It is well established that differences between languages in the boundaries of color terms induce corresponding differences in categorical perception in their speakers. For example, if a language A , like Greek or Russian, makes a simple lexical distinction between light blue and dark blue and language B, like English or Japanese, does not, speakers of A will reliably make finer discriminations at the boundary between light and dark blue than at the interiors of these categories and speakers of language B will not do this. There has been quite a bit of research on this question, some of it discussed in this forum: here, here, and here; all this research points to the conclusion that color naming differences across languages induce predictable differences in categorical perception of color.

A debated issue, however, concerns whether the word "perception" in the expression "categorical perception" is being used with sufficient precision. Are the observed effects truly perceptual or do they reflect a level of psychological — i.e., neural — processing that is either response-related or otherwise post-perceptual? Specialists in visual psychophysics and physiology (areas I am not expert in) are careful not to use the word "perception" loosely. However, consensus on a bright line criterion separating perception senso strictu from everything that take place in our brains downstream from perception does not, so far as I can tell, yet exist.

Some interesting new research both proposes a reasonable criterion for marking off perception per se from post-perceptual processing and demonstrates that language-induced (i.e., Whorfian) color CP is, by this strict criterion, perceptual. According to Thierry, Athanasopulous, Wiggett, Dering, & Kuipers, "Unconscious effects of language-specific terminology on preattentive color perception", PNAS (in press, 2009), neural activity is perceptual if it's both unconscious and pre-attentive. (I think some earlier color CP research can be argued to also meet this criterion, but that's a judgment call and this is a side issue, which doesn't detract in any way from the interest of the new stuff.)

[Note by Mark Liberman:The link is not yet live, although the paper was released from embargo on 2/16/2009, according to a note from editorial staff at PNAS; so until PNAS gets around to putting the paper on their site, a copy is here. A delay of up to ten days between the end of the embargo and "Early Edition" access is a typical pattern for PNAS, though the reason is unclear.]

Thierry et al. use an event-related potential (ERP) procedure, in which the subject is hooked up to an EEG recording device and the reaction of the brain's electrical activity is monitored while he or she is exposed to a series of stimuli. The series consists of repetitions of a "standard" stimulus, occasionally interrupted by a different, "deviant" stimulus. The brain has a characteristic way of reacting to a novel stimulus (of any kind), and according to Thierry et al. this reaction pattern is both unconscious and pre-attentive: unconscious because subjects are unaware of it and pre-attentive because in such experiments the subjects are instructed to react to some aspect of the stimulus unrelated to the property being monitored and the brain activity of the trials which elicit a response are not included in the analysis. For example, in this experiment the subjects were shown mostly colored circles with an occasional colored square and instructed to react when the stimulus was square. However, the brain wave patterns were analyzed only for constancy or deviance in the color of the circles, not the shape of the stimulus, which was the focus of attention. That part is crucial.

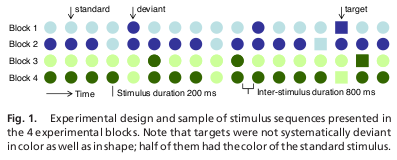

Subjects were speakers of either English, which makes no basic color term distinction between light and dark blue, or of Greek, which does: ghalazio and ble, respectively. Subjects of both groups were tested in four blocks of trials. The researchers "instructed the participants to press a button when and only when they saw a square shape (target, probability 20%) within a regularly paced stream of circles [of the same hue] (probability 80%). Within one block the most frequent stimulus was a light or dark circle (standard, probability 70%) and the remaining stimuli were circles [of the same hue] with a contrasting luminance (deviant, probability 10%), i.e., dark if the standard was light or vice versa." That is, there were trials of the types <standard: light blue, deviant: dark blue>, <standard: dark blue, deviant: light blue>, <standard: light green, deviant: dark green>, and <standard: dark green, deviant: light green>, as shown in Figure 1 from their paper:

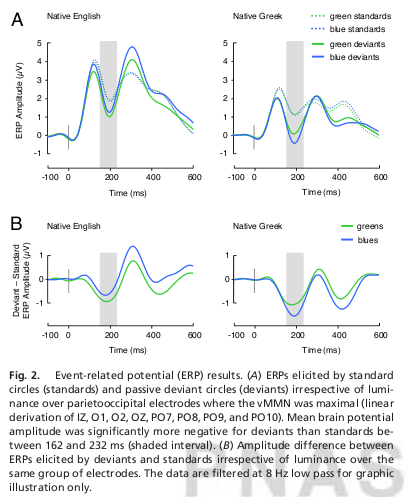

Trial type was cross-categorized with speaker type into four groups of trials, Greek-blue, English-blue, Greek-green, English-green. The standard novelty reaction ("visual mis-match negativity" or vMMN) occurs in the neighborhood of 200 milliseconds. This decrease in electrical potential was found to be significantly greater in the Greek-blue set of trials than in any of the other three sets, which were among themselves statistically indistinguishable, as shown in their Figure 2:

Unfortunately, the interpretation of the figure doesn't immediately leap out at the viewer, so here's part of the authors' statistical explanation:

Cricitally, we found no overall main effect of color (P > 0.1) or participant group (P > 0.1) and no significant color by group interaction on the mean amplitude of the vMMN but, as predicted, a significant, triple interaction between participant group, color, and deviancy (F[1, 38= = 4.8, P < 0.05; Fig. 2B). Post hoc tests confirmed that this interaction was generated by a differential vMMN response pattern in Greek and English participants, such that the vMMN effect was numerically (but not significantly greater for green than blue deviants in the English participants (F[1,38]=0.9, P > 0.1) but significantly greater for blue than green deviants in Greek participants (F[1, 38] = 7.1, P < 0.02), whereas the vMMN effect for green deviants was of similar magnitude in both the participant groups (F[1, 38] = 0.27, P > 0.1).

In less technical terms: Language differences in color categories were associated with differences between their speakers in perception in the strict sense of the word (well, at least in a strict sense of the word). The differences (in reactions to differences between within-category and across-category colors) were not large ones, but they were statisticially significant. And they were apparently too early to be the result of assigning and comparing color names on a given trial: they must have been the result of biases introduced into the color perception system itself.

So, what does this finding mean in the grand scheme of things? I think, if replicated, it suggests strongly that language difference can in fact influence perception. But now the question turns to the relative importance of that influence. The broadest Whorfian view espoused by serious contemporary experimentalists, such as Jules Davidoff, Debi Roberson, and (sometimes) Ian Davies, holds (or held until recently) that color terminologies can vary arbitrarily across languages, constrained only by the rule that a named category cannot occupy discontinuous regions of color space. (See, for example, Roberson, Davies & Davidoff 2000. Actually, their language is a bit vague on this, but here is not the place to sort out fine points of scientific rhetoric.)

However, several independent analyses of the World Color Survey data have shown beyond any reasonable doubt that this is not the case: there are universal tendencies in color naming across all languages (See, for example, Kay & Regier 2003, Regier, Kay & Cook 2005; Lindsey & Brown 2006; Griffin 2006; Kuehni 2007; Webster & Kay 2007; Dowman 2007). So languages may differ a lot in how they name colors, but these differences are constrained by a seeming master plan, which may have to do with our common internal representation of color space (Jameson & D'Andrade 1997, Regier, Kay & Khertepal 2007). A second constraint on wild Whorfianism is this: the color CP effect in speaking adults has been shown to be restricted (probably entirely, but certainly in major degree) to the right visual field, which projects to the left (language dominant) brain hemisphere (Gilbert et al. 2006, Drivonikou et al. 2007, Roberson, Pak, & Hanley 2008). This suggests that at every moment of perception, half of our visual input is filtered by language, but not the other half. Concurrent verbal interference (e.g., mentally rehearsing a long number name) has been shown in both lateralized and non-lateralized color CP studies to suppress the CP effect, indicating that neural representations of the named color categories are activated online during these experiments.

So it looks as if language may indeed influence color perception in a strict sense, but if that is true — and these results show surprisingly that it seems to be true — it does this in a way that is constrained by the facts that (1) there are cross-language commonalites in the internal representation of color and (2) that only half of our visual inputs are language-filtered.

References:

Cook, R. S., P. Kay, and T. Regier (2005). "The World Color Survey database: History and use". In Henri Cohen and Claire Lefebvre (Eds.), Handbook of Categorization in Cognitive Science. Elsevier.

Davidoff, J., Davies, I. & Roberson, D. (1999). "Colour categories of a stone-age tribe". Nature 398, 203-204.

Drivonikou G.V., P. Kay, T. Regier, R. B. Ivry, A. L. Gilbert, A. Franklin, & I. R. L. Davies (2007). "Further evidence that Whorfian effects are stronger in the right visual field than the left". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 1097-1102.

Franklin, A., Drivonikou, G.V., Bevis, L., Davies I. R. L., Kay, P. & Regier, T. (2008a). "Categorical perception of color is lateralized to the right hemisphere in infants, but to the left hemisphere in adults". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105, 3221-3225.

Gilbert, A. L., Regier, T., Kay. P. & Ivry R. B. (2006). "Whorf hypothesis is supported in the right visual field but not the left". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, 489-494.

Gilbert, A. L., Regier, T., Kay. P & Ivry, R. B. (2008). "Support for lateralization of the Whorf effect beyond the realm of color discrimination". Brain and Language 105, 91-98.

Kay, P. & Regier, T. (2003). "Resolving the question of color naming universals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100, 9085-9089.

Kuehni, Rolf G. (2007). "Nature and culture: An analysis of individual focal color choices in World Color Survey languages". Journal of Cognition and Culture 7, 151-172.

Lindsey, Delwin T. & Angela G. Brown (2006). "Universality of color names". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103, 16609-16613.

Regier, T., P. Kay, and R. S. Cook (2005). "Focal colors are universal after all". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102:8386-8391.

Regier, T., Kay, P. & Khetarpal, N. (2007). "Color naming reflects optimal partitions of color space". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 1436-1441.

Roberson, D., Davies I. & Davidoff, J. (2000). "Colour categories are not universal: Replications and new evidence from a Stone-age culture". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 129, 369-398

Roberson, D., Pak, H. J. & Hanley, R. (2008). "Categorical perception of colour in the left and right visual field is verbally mediated: Evidence from Korean". Cognition 107, 752-762.

Thierry, D., Athanasopulous, P., Wiggett, A., Dering, B., & Kuipers, J-R (2009) "Unconscious effects of language-specific terminology on pre-attentive color perception". PNAS (as of 2/22/2009, in limbo between embargo and Early Edition).

Webster, Michael A. & Kay. P. (2007). "Individual and population differences in focal colors". In: MacLaury, Robert E., Galina V. Paramei and Don Dedrick (eds.), Anthropology of Color: Interdisciplinary multilevel modeling. pp. 29Ð53.

Mossy said,

February 24, 2009 @ 9:51 am

Thanks for posting this. I can't believe I'm the only reader who finds this fascinating.

Ellen K. said,

February 24, 2009 @ 10:55 am

Wow. This explains pink and red, I think. :) As in, why they seem so distinctly different, whereas blue and light blue, green and light green, etc, don't seem so distinctly different.

Matthew Stuckwisch said,

February 24, 2009 @ 12:16 pm

Re the note that it can't be discontinuous, I wonder if magenta, which is an artificial colour, would have been more likely to be described a form of red or purple initially.

Also, at a more practical level, in teaching English to Spanish elementary kids, I've run into the overlapping/split colors issue with, of all things, hair color. Even though they know that "blonde" = "rubio/a", they're always calling people with light brown hair (or even what I'd call standard brown hair) blonde simply because a large part of the Spanish blonde spectrum is in what would be the brown spectrum for English speakers.

Mary Kuhner said,

February 24, 2009 @ 2:42 pm

Oliver Sacks' account (in _An Anthropologist on Mars_) of the painter who suddenly lost color-vision processing is interesting in this context. For unclear reasons (stroke, perhaps) the painter lost both color vision itself and the ability to remember or imagine colors.

I find this very odd because my subjective experience of my color memory is that it's mostly verbal; I remember how I categorized the color, not what color it was. This is even more true of my color imagination. (Characters in my stories have a distressing tendency to change eye and hair color, because I am not really visualizing them, just trying to remember what I wrote….) But the person in Sacks' account was a painter, and doubtless much more visually oriented than I am.

Can anyone think of a way to repeat the described experiment, but with memory or imagination rather than perception as the function being tested?

Mark F. said,

February 24, 2009 @ 4:10 pm

I wonder if there is a similar effect in communities where the colors themselves are viewed as carrying distinctly different meanings, even if they don't have different lexical names in the language. For instance, are basketball fans in North Carolina more like Russians or other English speakers in their blueness discrimination patterns?

Bryn LaFollette said,

February 24, 2009 @ 4:44 pm

I wonder whether describing this perceptual distinction as based on "language" is really accurate, as opposed to personal lexicon. It seems to me that breadth of color vocabulary varies a great deal from person to person within a given language, depending to a great deal on how much training an individual has had in, say, visual arts or interior design or what have you. Although broad generalizations based on the most commonly shared terms within a language will make differences between individual perceptions map nicely to distinctions of Language, I'm still skeptical as to whether this is really a distinction of specialized terminology and hence, personal lexicon; not really Language per se.

This doesn't take away from the facts of the experiment which I think are definitely interesting. I haven't yet read the article itself, but I wonder whether any control was factored into the experiment that would distinquished between the native language of the individual while ruling out personal lexicon distinctions of colors.

I'm fully ready to believe that the distinctions we have been trained to make (either by acquiring a language that makes certain distinctions in its basic vocabulary or having an occupation that depends on you being able to make fine, technical distinctions between categories for which technical terminology has been developed to label those categories) become at some level perceptual in the way described here. But, I would like to know whether this same effect would be seen in an experiment which had in place of English speakers and Greek speakers, something like Truckers and Non-Truckers (all speakers of the same language), and instead of examining distinctions of color, examining distinctions of big rig models.

Personally, I have a pretty broad background in visual arts and Art History. Looking at the colors shown above I immediately thought of them in the following categories: cerulean, purple, lime, olive. I can see how they might be described as light blue, dark blue, light green and dark green, but (and perhaps it's simply the effect of the web graphic) the colors in the figure above don't really fit as well with my conception of those descriptions.

bianca steele said,

February 24, 2009 @ 4:53 pm

Ditto what Mossy said.

A similar question to the one raised by Mark F.: Are Philadelphia football fans gradually losing their ability to differentiate between shades of green?

Bryn LaFollette said,

February 24, 2009 @ 4:54 pm

Er… By "the effect of the web graphic", I really meant to say "an artifact of this being a web graphic".

Noetica said,

February 24, 2009 @ 5:06 pm

Mossy, why do you think you are the only reader who finds this fascinating? People may be slow with comments only because it is a long and technical post that strays beyond linguistics proper.

Ellen K., how any of this fits with pink and red is problematic. Don't more languages assign "light red" its own name than assign "light green" or "light blue" their own names? Shouldn't we then suspect that something non-linguistic determines the linguistic facts, rather than the other way around?

Matthew Stuckwisch, I for one would like to understand this point of yours better:

Paul Kay, I am interested in this sentence for a few reasons:

(You might like to amend senso strictu to sensu stricto.)

One lurking assumption may be that a principled and serviceable distinction between "perception" and "everything that take place in our brains downstream" from it is even possible. I wonder also whether such a distinction could ever be better than arbitrary and conventional. It is not clear that distinctions are findable (or as obvious as we had thought, or as objectively based) first between sensation and perception, and second between perception and cognition (that is, cognition that is not also perception). It seems to me that there is a great deal of pure conceptual analysis to be done before much can be made of these empirical studies.

You yourself mark this sort of question as important:

I just suggest that the debate ought to be broader than that. I hope it is broader, somewhere!

Thanks for the post. I hope there will be more commentary.

KYL said,

February 24, 2009 @ 5:35 pm

I believe we've also shown that the ability for people to distinguish between different phonemes is also altered by the language they speak (e.g., if your language doesn't treat "r" and "l" as two distinct phonemes, you literally have a diminished perception of the difference between the sounds). I hope I got the terminology right.

The color perception issue is very similar, no? Some weak form of the Whorfian hypothesis would seem to be supported by evidence.

Mark F. said,

February 24, 2009 @ 5:59 pm

Bryn — I have to suspect that personal color lexicon is the determining factor, since after all that's the language that you speak. But 'cerulean' is learned later in life than 'blue.' I think it's an interesting question how much of a difference it makes how long the person has had words for the different colors. I could imagine color words learned after childhood having no effect, or (less likely perhaps) being just as effective. Or maybe it takes half a decade from whenever you start regularly using the word for it to alter your perception.

Jongseong Park said,

February 24, 2009 @ 6:02 pm

KYL: Isn't diminished perception of the difference between sounds that fall within the same phonemic category limited to what the brain perceives as speech sounds? That's a very narrow subset of sounds that we perceive, whereas everything we perceive visually has an associated colour. Nevertheless, I see your point that something similar might be at work here.

I don't know how relevant this is to the discussion if at all, but I've wondered before whether our familiarity with certain musical scales affect our perception of musical intervals or pitch differences in general. Then again, only those with musical training would really have that 'vocabulary' of different intervals whereas colour vocabulary is universal.

Paul Kay said,

February 24, 2009 @ 8:47 pm

Noetica, thanks for the interesting and provocative comment (and for exposing me as a Latin poseur).

You write: 'One lurking assumption may be that a principled and serviceable distinction between "perception" and "everything that take place in our brains downstream" from it is even possible. I wonder also whether such a distinction could ever be better than arbitrary and conventional. It is not clear that distinctions are findable (or as obvious as we had thought, or as objectively based) first between sensation and perception, and second between perception and cognition (that is, cognition that is not also perception).'

I'd like to hear more about this. Do you come to this view on the basis of new evidence, a gut feeling that if by now a fine line has not be found it probably doesn't exist, or what? I'm not a student of perception. But my impression from talking to students of perception is that they mostly have the kind of attitude toward defining perception that Justice Stewart had toward defining obscenity: "I know it when I see it." I'm not yet as ready as you seem to be to give up on the search for objective criteria, but I grant that your attitude is a reasonable one. Doubt is seldom misplaced.

You continue: 'It seems to me that there is a great deal of pure conceptual analysis to be done before much can be made of these empirical studies.'

Here I bridle a little. It sounds as if you're saying the best way for knowledge to proceed is for philosophers to map the terrain from the air before the scientists are let loose on the ground. I hope that's unfair to your intention because I don't think that's the way it works when it works well. For example, I think Thierry et al.'s criterion of "both unconscious and pre-attentive" as a necessary (if not sufficient) condition for perception is worthy of our attention.

Paul

njunior said,

February 24, 2009 @ 10:15 pm

Does this mean that Sapir and Whorf were right?

Paul Kay said,

February 24, 2009 @ 10:53 pm

njunior, I think it means that Sapir and Whorf were not totally wrong. I also think that if you had read more carefully, I wouldn't have needed to point that out.

Paul

Mossy said,

February 25, 2009 @ 3:37 am

@ Noetica

I was surprised because anything on LL that touches on Whorfian theories usually sets off a lively discussion immediately.

For what it's worth — and I would like to state very loudly that this isn't worth much — a few years ago I did a highly unscientific study of color descriptions in Russian and English. I wanted to find out: If a Russian said X color, what should the English translation of that color be? It was simple until we got to the purple (in English terminology) range. There was more disagreement among Russian speakers (they used different words to describe colors in what I, an English speaker, would call the light purple range). And there was a huge difference between Russians and English-speakers in the dark-blue-purple range. What Russians called dark blue, English-speakers called purple or dark purple. (In the south of Russia eggplants are called "little blue things.") There were also differences between Russian and English-speakers in what the Russians called the "light blue" range.

Stephen Jones said,

February 25, 2009 @ 5:20 am

No. The ability to distinguish between the phonemes of the mother language is one that is learned in the first year of life. About 20 years ago Scientific American carried an article which showed that at three months babies were able to distinguish different sounds, but if they were not separate phonemes in the mother tongue they were no longer able to distinguish them at I think one year. It appears to be the first stage in language acquistion.

We can of course relearn how to distinguish, either unconsciously if the second language is learned as another mother tongue before puberty, or consciously thereafter.

However, whilst an Arab speaker can be taught to distinguish between 'b' and 'p' if he's not taught he will hear them as the same. If you're language only has one primary color word for 'brown', like English, then you will find it slightly more difficult to distinguish between beige and other shades of light brown than will a Spaniard for whom 'beige' is a primary color word.

(By 'primary color word' I am referring to the fact that in the languages I speak there is a range of words that combined with 'light' and 'dark' can perfectly adequately describe any color in the spectrum. These words do not map equally across languages; an English speaker could describe a beige pair of trousers as being 'light brown', but the Spaniard would think he needed to go to the optician, as 'beige' is a primary color word in Spanish. The Barcelona Football team are sometimes call the 'blaugrans' because the second color on their shirt, 'granate', is a primary color word in Catalan).

I'm another one by the way who found this article fascinating.

Stephen Jones said,

February 25, 2009 @ 5:23 am

I thought Whorf only added Sapir's name to the hypothesis in order to give it some kind of spurious authority.

Stephen Jones said,

February 25, 2009 @ 5:24 am

It would be interesting to carry out this experiment with bilinguals; both those with two mother tongues, and those who learned and not acquired their second language.

Mossy said,

February 25, 2009 @ 5:48 am

@Stephen Jones

Or to differentiate for gender.

Noetica said,

February 25, 2009 @ 6:05 am

Mossy, thanks for clarifying. It still seems to me that the slight delay is accounted for by the difficulty of the article discussed – at least for readers of a blog centrally concerned with linguistics rather than neuroscience. Good to see a steady flow of interest now.

Paul, let me take up this point first:

I'm sorry if sounded that way. I merely reported how things "seemed to me" about what is desirable "before much can be made of these empirical studies." I certainly did not mean that such empirical studies were nugatory, or to be kept on hold until philosophers had scouted the terrain first! In fact, I think it is imperative for progress in all of the relevant disciplines that their practitioners talk to each other progressively, about their parallel findings and conjectures.

As for my remarks that you have asked to hear more about, I'll address your specific questions and observations:

I come to question the assumption that there are clear conceptual boundaries between sensation, perception, and indeed non-perceptual cognition not through any new evidence, nor through any original empirical research, nor from any gut feeling. I come to do it from a dissatisfaction with prevailing accounts of the supposed differences: from the sketchiness of some accounts, from what I see as a general lack of consistency, and from the testimony of those some who have wrestled with these terms.

Let me cite Hardin (from the 1988 edition of Color for Philosophers, which is the edition I have to hand):

Perhaps this illustrates both the fugitive nature of the terms, concepts, and domains of interest (taking the term sensory as a reasonable stand-in for sensation) and the fact that one esteemed author at least uses the terms differently from (for example) Thierry et al., who make no mention of sensation or the sensory, though surely they and Hardin are talking about the same sorts of interactions between supposed "naturally distinct" levels.

Some have questioned how natural or unassailable those distinctions are. This is from "Sensation and Perception Research Methods", Lauren Fruh VanSickle Scharff, in Handbook of Research Methods in Experimental Psychology, 2003:

Or consider this from Handbook of Psychology, History of Psychology (Volume 1), Freedheim and Weiner (eds.), 2003:

Such opinions are easy to track down; and it is problematic how they fit with projects such as that of Thierry et al. After all, aren't Thierry et al. at the forefront of tackling just those very distinctions? Perhaps. But I would like to see a more explicit pursuit of this conceptual inquiry: if not by these authors, then following closely upon their excellent empirical work.

I certainly respect that important and procedurally meticulous work, though I could quibble with some details. I think there could have been more background concerning the words for shades of blue in Greek. The words might have been given in their original Greek form; it might have been explained that what they present as ble (μπλέ) is close in sound to English blue, and has an alternative form (μπλού) that sounds practically the same as blue. It is interesting also that a less equivocal word for a dark blue, μαβής (from Turkish), is not mentioned. Oddly, one of my dictionaries shows both the colour words that they use as translatable by azure. Such details might conceivably be relevant in teasing out what's going on linguistically and "cognitively" for those speakers of Greek with English as a second language, currently living in an English-speaking environment. We are not told, but presumably the experimenters interacted with the subjects only in English, so that the general "set" was English. Overall, it might have been better to use only two cohorts of comparable monolingual subjects in comparable locations in the UK and Greece. No doubt the experimenters would have preferred this, but of course it would be expensive and logistically difficult to achieve.

Finally, you write:

So I think we agree on a lot, but our general orientations are different. I will say this: while the Stewart approach may work in most cases, it is insufficient when the work is exactly and intentionally at the boundaries. There could be no adequate account of blindsight using a Stewart approach to the traditional categories, and I doubt that anyone restricted to such an approach can do justice to the exploration of Whorfian hypotheses either.

Stephen Jones said,

February 25, 2009 @ 7:14 am

I think the main reason people didn't comment was simply that the OP was uncontroversial. I read the post almost as soon as it appeared, and the only comment I could think of was 'this is the kind of post I'd like to see more of'.

And it would have been a waste of space to have posted that.

Now once some people have posted there are comments to post on. Nobody here is actually commenting on the original post; they are all commenting on the comments.

Matthew Stuckwisch said,

February 25, 2009 @ 7:57 am

Noetica, what I meant by the comment with magenta is that it was a colour which does not singularly exist in the light spectra. If you take a color wheel and map it to the visible spectra, you don't have a gap between red and purple with no corelation (red is large wavelength and purple is small). Magenta of course is the color we are now taught goes in between red and purple. But although on level it's considered a pure color, it's really made of both red and purple (or rather, white minus green). Other colors can be made with a single wavelength (plus "the rest of the spectrum" to make "light" colors). But whereas we perceive on computers, for instance, the presence of green and red as a single wavelength corresponding to yellow (which can exist as a single wavelength), magenta is also perceived a single wavelength which of course it is not and cannot be.

The color magenta was predicted before its actual discovery in the 19th century, and it's so called because of the city in which it was found. Note the distinctive lack of magenta in painting until more modern times. So, previously this word did not exist. Had someone encountered the color prior to having a name for it, given that in theory it exists between red and purple on imaginary spectrum, would different languages identify it as being a variety of red, or of purple (or blue-green or whatever best describes their color system), or would they all prefer the description of red, or might there be patterns to it? Of course it's a very hypothetical question and probably impossible to test.

Ellen K. said,

February 25, 2009 @ 9:02 am

Matthew, same for purple. Okay, violet can be considered a kind of purple, but for the most part, purple is a combination of red and blue. Magenta also can be considered a kind of purple.

bianca steele said,

February 25, 2009 @ 10:17 am

This may sound ignorant, but the kind of discussion Paul Kay and Noetica are having takes place all the time among scientists, right? It would be nice to have a description of all the interactions that take place during the exploration of some topic, along the lines of what Bruno Latour does in Laboratory Life. A historical study might work instead, but in my research I've too often found that there are gaps in the record.

Boris said,

February 25, 2009 @ 10:31 am

Well, I am bilingual (Russian and English, having learned English starting at age 11) and while I'm much more comfortable with English these days, I am puzzled by some statements above regarding how color is perceived in English.

I would never confuse any shade of blue with any shade of purple, at least in my mind. Also, I make a clear distinction between purple (which has no commonly used analog in Russian) and Violet (which is not as commonly used in English, but has the same root as the commonly used Russian word).

In fact, I'm quite defensive about this point, since my favorite color (going back to when such things mattered to me) is violet (darker than purple in my mind), and I just think of purple as too close to pink, which is definitely not my favorite color. Of course, if I were talking about purple in Russian, I would use the Russian equivalent of violet. Not vice versa, though.

As far as shades of blue, I will identify both Russian shades of blue as blue in English. As for the colors above, I would call both of them Blue in English and make the distinction in Russian. Though the dark blue pictured above has a component of violet in it, it is not enough to call it that in either language, and it is definitely not a shade of purple.

Mossy said,

February 25, 2009 @ 1:28 pm

Boris, what color would you call eggplants in Russian?

Mossy said,

February 25, 2009 @ 1:32 pm

Another question for all: the paper doesn't describe gender of the participants. Does that bother anyone?

Noetica said,

February 25, 2009 @ 8:01 pm

the paper doesn't describe gender of the participants. Does that bother anyone?

An Australian asked an American guest if he wanted his coffee without milk, and the guest replied that he would prefer it without cream, thank you.

I'd rather be bothered that the sex of the subjects was not reported, thank you. This may not always be useful information, and there may sometimes be "political" reasons to act against the orthodoxy that sex is inevitably a crucial variable. But in the present case some readers may reasonably deem it relevant, and it would have cost nothing to assure them that results were not skewed by an imbalance between the groups.

Stephen Jones said,

February 26, 2009 @ 12:22 am

Yea, and what about sexual orientation. I mean we can surely expect gays to be better at discerning the pastel shades.

And hair color

Mossy said,

February 26, 2009 @ 1:38 am

Jeez, why are you so snide? For folks who rant against prescriptivism, you're awfully quick to pull out that ruler and smack my hand.

I could be wrong, but my guess is that women are socialized to distinguish colors (although I have no idea how universal/common this is). So if all the Greek participants were women, or if all the English participants were, then the findings might be skewed.

You might respond to that. Or you might just continue to sneer.

Noetica said,

February 26, 2009 @ 2:30 am

Um, I hope that was addressed to Stephen Jones and not at all to me, Mossy! Myself, I agree with you entirely. The only adjustment I sought to make was to have the male–female variable labelled sex, not gender.

Note that the word Thierry et al. present as ghalazio is closely related to the standard word for milk (cognate with our word galaxy, as in "Milky Way"; and less directly all the Latin lact- words that we inherit). Apparently that is why it refers to a light "milky" shade of blue. Is there a special female response to that? And while we're free-associating, the term seems to occur in a familiar patriotic epithet for the blue-and-white Greek flag: "γαλάζιο και λευκό".

All Greeced for the mill.

Boris said,

February 26, 2009 @ 10:41 am

Was my eggplant post deleted? I don't see how it's off topic.

Arnold Zwicky said,

February 26, 2009 @ 11:09 am

These comments about sex and sexual orientation are carrying things off the original point and into "N words for X" territory. The original posting was not about discriminating colors in general, or about knowing lots of words (or few words) for shades. It was specifically about the basic color categories within some group of people and about the associated vocabulary ("basic color terms").

Boris said,

February 26, 2009 @ 12:15 pm

Oops, sorry. Posted in wrong topic

well, eggplants come in different colors, so depending on that, I would call it either violet or бардовый (which Wikipedia translates as maroon. Another color word in much more widespread use in Russian than in English).

Felix said,

February 26, 2009 @ 12:39 pm

On the topic of gender and sexual orientation, and maybe I'm stretching these concepts a bit but, these topics are directly related to my own experience with language impacting how I think.

In the early 90s I was a member of an activist organization dedicated to advancing rights for gay, lesbian, and bisexual communities. The group was called Queer Nation. At the time, this name was quite controversial: I regularly read letters to the local gay newspapers decrying the use of what had historically been an epithet. Our perspective was that by loudly using the word ourselves, we were reducing its ability to hurt us. Queer Nation was more or less known for using a lot of day glow stickers with phrases on them like, "faggot", "dyke", etc. Almost 20 years later, I think it is inarguable that mainstream attitudes towards gay, lesbian, and bisexual folks have changed significantly. I know in my own experience, that my choice to use these words changed how I think of myself. Calling myself a queer was an antidote to shame and embarrassment about my queerness. What's up in the air for me is whether our own use of language influenced public attitude about us.

(The contemporary use of the word 'nigger' in black communities deserves a separate and larger discussion, and certainly has a different context and history than the use of the world 'queer', but probably has some parallels in the sense that some feel they can take the power out of a painful word by using it among friends – even if it would be inappropriate coming from those from historically oppressive outside groups.)

One thing that interests me about the world queer is how it's now used as an umbrella term for a pretty diverse community. The only other option is some variant of GLBT, a clunky acronym that doesn't work for every application (I would never call myself a "GLBT person", for example). Before Queer Nation, the word 'gay' was used as the umbrella, yet this word also essentially meant and still means homosexual man. So the term used to describe an entire community simultaneously excluded the majority of that community. The most obvious parallel I can think of for this is the use of the world, "man" to mean "humans".

That parallel word brings up a whole 'nother set of intentional linguistic choices that 2nd wave feminists advocated: re-spellings of woman (wimmin, etc) for example. The social impact of alternative spellings of woman is questionable but I can't help but think that my daughter benefits from growing up in a time where "he" and "man" are less likely to be used as the default and that her imagination of what is possible for girls and women is expanded not just by the examples of powerful women in her life, but also by hearing the phrase, "he or she" instead of always only "he".

Maybe I'm misunderstanding or extending the basis of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis too far by applying it to these specific words within our language. Still, I can't help but think that how we talk makes a difference to how we think.

vaardvark said,

February 26, 2009 @ 3:13 pm

I don't understand why this is something new. Rosch had papers on influence of language on color perception back in mid-70s, around the time she published Natural Categories. I discussed this issue with Rosch, Dreyfus and Searle back in 1991–admittedly, none of these people were experimentalists and the exchanges were never published, but it's been a known cognitive issue for some time, which is precisely why no one thought it important to bother with publication. Is there no communication between linguists and the rest of the cog-sci community? All the references, save two, are post-2005. And the earliest two are from 1999 and 2003. What? No reads further back than 10 years any more? And this has certainly been an issue in cognitive philosophy long before anyone ever considered the effects to be "Whorfian " or even had a term for "cognitive".

Or am I completely missing an elephant in the room?

Mossy said,

February 26, 2009 @ 4:05 pm

@ Arnold Zwicky

Sorry. Didn't quite get this. I see that the experiment had to do with basic colors (and apologize for getting off topic). Do you think that the sex of the participants could not be a factor? Perhaps I'm mixing apples and oranges.

Stephen Jones said,

February 26, 2009 @ 10:21 pm

I presume that on the basis of prior research in the field they decided that sex would not be a factor in this particular experiment at these parts of the spectrum.

Here's a link to a paper by Kimberly Jameson, who appears one of the leading experts in the field.

http://aris.ss.uci.edu/~kjameson/JHW2001.pdf

Here's a link to her webpage where you can download other articles if you think necessary.

http://aris.ss.uci.edu/~kjameson/kjameson.html

Stephen Jones said,

February 26, 2009 @ 10:26 pm

Isn't the important thing about the research that it is showing where, neurologically, the discrimination occurs.

Interesting Stuff: February 2009 (II) « The Outer Hoard said,

February 27, 2009 @ 4:23 am

[…] An experiment showing one way in which colour perception in the brain is influenced by language. […]

Arnold Zwicky said,

February 27, 2009 @ 9:20 am

To vaardvark, about the recency of the references: I assume that Paul Kay was just following the customary practice of citing research that was both directly relevant to the issue and up-to-date. He could, of course, have cited the classic book:

Berlin, Brent & Paul Kay. 1969. Basic color terms: Their universality and evolution. Berkeley: Univ. of Calif. Press.

(and later articles on categorical perception of basic colors).

As Stephen Jones pointed out, what's new in the research Paul reported on is the attempt to tease out just where, neurologically, the effect occurs.

Paul Kay said,

February 27, 2009 @ 1:26 pm

vaardvark writes:

I don't understand why this is something new. Rosch had papers on influence of language on color perception back in mid-70s, around the time she published Natural Categories. I discussed this issue with Rosch, Dreyfus and Searle back in 1991–admittedly, none of these people were experimentalists and the exchanges were never published, but it's been a known cognitive issue for some time, which is precisely why no one thought it important to bother with publication. Is there no communication between linguists and the rest of the cog-sci community? All the references, save two, are post-2005. And the earliest two are from 1999 and 2003. What? No reads further back than 10 years any more? And this has certainly been an issue in cognitive philosophy long before anyone ever considered the effects to be "Whorfian " or even had a term for "cognitive".

*****************

Let me correct a few things:

1. In answer to the rhetorical question, "What? No [sic] reads further back than 10 years any more [sic]?' the original Thierry et al. paper cited: Whorf (1940), Vygotsky (1934), Brown & Lenneberg (1954), Heider [= Eleanor Rosch] & Olivier (1972). [See the original paper for the full references: http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0811155106. If the link is still not live, the link that Mark put in my original post will be.].

2. Eleanor Rosch [then Eleanor Heider] most certainly was an experimentalist.

3. She did not write "papers on influence of language on color perception back in mid-70s," or at any other time. On the contrary her papers on color and language sought to show that universals of color representation (read "perception" if you like) in the form of the universal focal colors proposed by Berlin and Kay in 1969 showed up in memory and grouping tasks by speakers of a language, the Dugum Dani of New Guinea, whose color language did not directly reflect the universal focal colors. The central thrust of her work on color was, if anything, against the idea of the influence of language on color perception.

4. On, "it’s been a known cognitive issue for some time, which is precisely why no one thought it important to bother with publication," important recent experimental work by Roberson, Davidoff, Davies, Boroditsky, Özgen and others have seriously challenged Rosch's classic findings on the immunity of color perception/cognition to color naming. Most of this work cites the earlier experiments of Kay and Kempton (American Anthropologist 1984, 85: 65-79) comparing color similarity judgments between Americans and speakers of Tarahumara, a language that does not lexically distinguish between green and blue. [Apologies for blowing my own horn, but the reason for the citation is to illustrate the continuity of experimental interest in the subject from Brown & Lenneberg in 1954, through Rosch [Heider] in the 70s, through Kay & Kempton in the 80s to the recent work of the 90s and (hmm.. What do we write… 00s? If so, how do we pronounce it?).]

5. Vaardvark complains: "I don’t understand why this is something new." The answer to the embedded question would seem to lie in one of two places. Vaardvark either simply misremembers what's old or supposes that when an extremely broad philosophical question is raised, like "Is there any relation between language and anything else in our heads?' that the subject has been exhausted. Or both.

Please forgive the uncompromising tone but facts are facts. I believe in the first amendment, but rights entail corresponding responsibilities.

Paul

David Marjanović said,

February 27, 2009 @ 6:03 pm

Ah, good to know that beige is considered a kind of brown in English. Nobody ever told me! In German, it's a somewhat rare but primary color term, and "light brown" is more like hazel.

Katherine said,

March 1, 2009 @ 9:29 pm

None of this takes into account any kind of colourblindness or physical differences that make people perceive colours differently to others.

My sister and I recently had an argument over the colour of a pair of her shorts; she called them orange when I referred to them as pink. Neither of us could what the other called the colour. She said she would sooner call them red than pink and I swore that there was no orange in them. We both agreed on scarlet however. I am slightly less sensitive to different colours than is normal. She has a tendency to be hypersensitive to small things, though I'm not sure how we could test whether that extends to colour as well.

The "dark blue" in the experiment is just that, dark blue. I'm not sure why some of you think it has passed the end of the blue range and headed into purple (indigo, violet, whatever you want to call it) territory.

Leonid Perlovsky said,

December 31, 2009 @ 8:24 pm

Dr. Kay's proof that or brain is Whorfian (=language affects cognition) is a great first step. I suggest that the human cognition, consciousness, and culture requires EMOTIONAL connections between LANGUAGE and COGNITION. (Without emotions we would not care.) Different languages have DIFFERENT EMOTIONALITIES. Therefore I propose

Leonid Perlovsky said,

December 31, 2009 @ 8:25 pm

Therefore I propose EMOTIONAL WHORF hypothesis

The Science Essayist » The Naming of Things (Part I) said,

June 29, 2010 @ 11:25 am

[…] the shapes of various stimuli, not their colors. (The paper, along with a few caveats, is detailed here by Language Log. The most interesting caveat has to do with the suggestion, drawn from previous […]