Legal lexicography

« previous post | next post »

Eugene Volokh ("What does 'exposes' in '[a]ny person who abuses, exposes, tortures, torments, or cruelly punishes a minor' mean to you?", Washington Post 1/2/2015) considers the case of Douglas James Myers, who was clocked driving at 112 mph, "weaving all over the road and going into the ditch or median with all four tires", with a blood alcohol level of 0.131 and four small children in the car:

Myers pleaded guilty to driving under the influence (his third offense); but he was also charged for violating S.D. Codified Laws 26-10-1, which provides that “[a]ny person who abuses, exposes, tortures, torments, or cruelly punishes a minor” is guilty of a felony. He argued that the term “expose” in the law was unconstitutionally vague, but the trial court rejected the argument and found him guilty, sentencing him to five years in prison on the “expose” charge.

Myers appealed to the South Dakota Supreme Court, which rejected his argument […]

Prof. Volokh doesn't think that expose as a transitive verb, standing alone without a to-phrase, can mean “to lay open to danger, attack, harm, etc.” unless "unless some context strongly suggests it". I agree with him about this, but I'm not so sure about the interpretation that he proposes instead:

Rather, I think that “expos[ing]” a child, absent some more specific contextual cues, generally means intentionally leaving a child exposed to the elements. In the words of one dictionary published around 1903, when the South Dakota statute was enacted,

To place or leave in an unprotected place or state; specifically, to abandon to chance in an open or unprotected state; as, among the ancient Greeks it was not uncommon for parents to expose their children.

The South Dakota statute under discussion is 26-10-1:

26-10-1. Abuse of or cruelty to minor as felony–Reasonable force as defense–Limitation of action. Any person who abuses, exposes, tortures, torments, or cruelly punishes a minor in a manner which does not constitute aggravated assault, is guilty of a Class 4 felony. If the victim is less than seven years of age, the person is guilty of a Class 3 felony. The use of reasonable force, as provided in § 22-18-5, is a defense to an offense under this section. Notwithstanding § 23A-42-2, a charge brought pursuant to this section may be commenced at any time before the victim becomes age twenty-five.

If any person convicted of this offense is the minor's parent, guardian, or custodian, the court shall include as part of the sentence, or conditions required as part of suspended execution or imposition of such sentence, that the person receive instruction on parenting approved or provided by the Department of Social Services.

The source is given on the cited web site as

Source: SDC 1939, §§ 13.3301, 13.3303; SDCL § 26-10-5; SL 1969, ch 32; SL 1975, ch 179, § 1; SL 1977, ch 189, § 96; SL 1983, ch 211, § 2; SL 1998, ch 162, § 3; SL 2001, ch 145, § 1; SL 2008, ch 140, § 1.

so I'm not sure that the wording in question really dates back to 1903 (though perhaps Prof. Volokh got this date from an authority with a longer memory). In any event, exposure in the ancient-Greek sense doesn't strike me the sort of thing that people would plausibly have been legislating against, either in 1903 or in 1939, by simply forbidding adults to expose a child — at least not without some further specification of what that crime involves. And the rest of the South Dakota statute in question is about abuse or cruelty, not about abandonment or terminal neglect.

Are there other laws from that period using the word expose in the sense of "abandon[ing a child] to chance in an open or unprotected state", with or without giving any further definition?

Instances of the word expose in current federal regulations are mostly or entirely in the form of the -ed participle, used either in the sense of proximity to infections, parasites, or radiation, or else in the sense "uncovered":

9 CFR 73.8 – Cattle infected or exposed during transit.

9 CFR 72.1 – Interstate movement of infested or exposed animals prohibited.

40 CFR 197.21 – Who is the reasonably maximally exposed individual?

9 CFR 50.8- Payment of expenses for transporting and disposing of infected, exposed, and suspect animals.

16 CFR 1611.34- Only uncovered or exposed parts of wearing apparel to be tested.

And in the works of the South Dakota legislature, most of the other uses of expose are in the context of poker regulations, e.g. Rule 20:18:16:15.04, dealing with "Phil 'em up poker":

(8) The dealer starts from the dealers left side and continues around to the last player. The cards are to be dealt in the following manner:

(a) The dealer places one card in front of each player who has placed a bet in the betting spot. This card is placed face down;

(b) The dealer deals the dealer two cards face up which are community cards;

(c) The dealer then places another card in the discard rack. This is the second burn card;

(d) Then the dealer gives each player a second card. After each player receives a second card, the dealer deals the dealer a third community card face down. After all cards have been dealt, the dealer places the remaining cards into the discard rack without exposing the cards;

(e) The dealer starts from the dealer's left and continues to the right and asks each player if the player would like to double down;

(f) If a player does double down, the dealer shall ask the player to place the player's cards face down tucked under or to the right of each player's bet;

(g) The dealer then exposes the dealer's third community card;

(h) The dealer starts from the dealer's far right and exposes each player's two cards. The dealer then reads each player's hand to determine if the hand is a winning hand of 10's or better; and

(i) After reading each player's hand to see if the hand is a winning hand, the dealer either takes the losing bet or pays the winning hand according to the payout schedule listed above. Then the dealer shall place the player's cards in the discard rack. The dealer continues to do so until each hand is read.

Can anyone offer any other evidence about what expose might reasonably be taken to mean, in the context of the phrase "Any person who abuses, exposes, tortures, torments, or cruelly punishes a minor in a manner which does not constitute aggravated assault"?

Update — Simon Spero (in the comments) cites the (a?) 1903 source for the current language of the South Dakota law, which gives substantial credence to Eugene Volokh's interpretation:

§ 1. Children—Cruelty To, Prohibited.] It shall be unlawful for any person having the care, custody or control of any child under the age of fourteen years, and for all other persons, to exhibit, use or employ such child either as a mendicant, or peddler, or actor, performer or singer on the streets, or in any concert hall or room where intoxicating liquors are sold or given away, or in any variety theater, or for any illegal obscene, indecent or immoral purpose, exhibition or practice whatsoever, or for any business, exhibition or vocation injurious to the health or morals or dangerous to the life or limb of such child, or cause, procure or encourage such child to engage therein; or wilfully, negligently or unnecessarily to expose, torture, torment, cruelly punish, or wilfully neglect such child or deprive such child of necessary food, clothing, shelter or medical attendance.

And Tom O. cites a relevant Michigan statue:

Here's a statute from Michigan that uses the word "expose" without a to-phrase to mean abandon: "Except as provided in subsection (3), a father or mother of a child under the age of 6 years, or another individual, who exposes the child in any street, field, house, or other place, with intent to injure or wholly to abandon the child, is guilty of a felony, punishable by imprisonment for not more than 10 years." MCL 750.135(1). The language tracks back to "section 31 of Ch. 153 of R.S. 1846, being CL 1857, § 5741."

The 1846 statute was interpreted in Shannon v People, 5 Mich 71 (1858) [Google Books link]. The interpretation starts at the bottom of page 89. The Michigan Supreme Court notes that the Michigan statute was copied from the New York Revised Statutes, and that the term "expose" was not a legal term of art. After reviewing various definitions, the court seems to adopt the "leaving or abandoning" definition. (Page 92.)

Update #2: Eugene Volokh writes:

Two thoughts:

1. The original version of the South Dakota statute does indeed seem to come from 1903, as your reader Simon Spero noted. The Westlaw statutory history is often incomplete, but HeinOnline is more thorough.

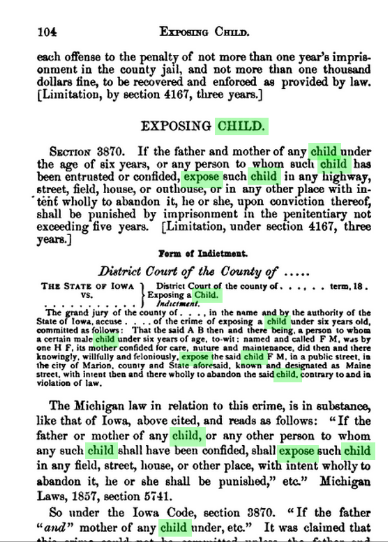

2. I appreciate that concern about exposing children would likely have largely retreated even by 1903. Still, there are quite a few statutes from that general era that indeed ban “exposing” a child in a public place “with intent wholly to abandon it,” and “expose” without any qualifier is sometimes seen as being shorthand for that. See, e.g., from the neighboring state of Iowa [J.C. Davis, Iowa Criminal Code and Digest and Criminal Pleading and Practice 96 (187)]:

The 1907 Iowa case I cited in the post likewise at one point refers to the statute as barring “exposing a child under the age of six years.” I imagine such actions were rather rare by then, but they still happened enough to draw the attention of courts and legislators.

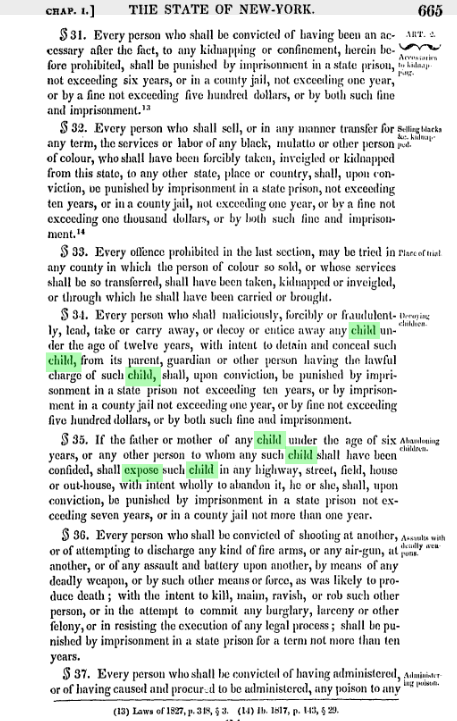

3. Finally, a quick HeinOnline search reports that similar laws banning exposing children in public places date back at least as early as the 1820s; see, for instance, this New York statutory compilation [The Revised Statutes of the State of New York: Passed during the Years One Thousand Eight Hundred and Twenty-Seven, and One Thousand Eight Hundred and Twenty-Eight: to Which Are Added Certain Former Acts Which Have Not Been Revised 655 (1829)]:

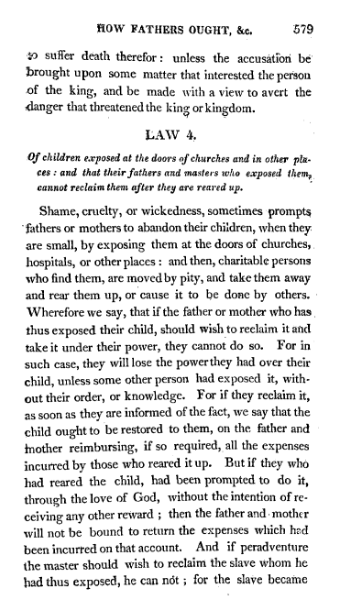

The Iowa statute might thus have just been an adaptation of those old laws, which doubtless date back earlier still – legislatures are of course famous for adapting old statutes from other states, with all the terminology those statutes contain. There is an interesting twist in the 1820 translation of the Louisiana Code, though, which might help explain the inclusion of exposure in a “house” together with exposure outdoors in the other statutes; “expose” seems to have by then also included, by analogy, leaving children in places where they are sure to be found, and thus abandoning them to the charity of others, and not just abandoning them to die:

I'm convinced by Prof. Volokh's arguments that he is right about the meaning of "expose" in the 1903 version of the statue:

It shall be unlawful for any person having the care, custody or control of any child under the age of fourteen years, and for all other persons, […] wilfully, negligently or unnecessarily to expose, torture, torment, cruelly punish, or wilfully neglect such child or deprive such child of necessary food, clothing, shelter or medical attendance.

In subsequent re-writing, the list of verbs was made finite rather than infinitival, and "wilfully neglect or deprive such child of necessary food, clothing, shelter or medical attendance" at the end was removed in favor of "abuses" at the beginning:

expose, torture, torment, cruelly punish, or wilfully neglect or deprive such child of necessary food, clothing, shelter or medical attendance

→ abuses, exposes, tortures, torments, or cruelly punishes [a minor in a manner which does not constitute aggravated assault]

In the context of the new version alone, "exposes" is pretty much uninterpretable, it seems to me — forced to make something up, I would have guessed that it meant something like "display without clothing".

Against the background of the earlier versions, Prof. Volokh's interpretation is clearly correct — though I wonder how many of the intervening legislators would have understood things that way. In either case, the court's decision seems to be wrong, as he argues.

===Dan said,

January 4, 2015 @ 2:38 pm

This isn't legal evidence, but it seems to me that it's strange to see "expose" without explicit reference to what: the elements or risks or bad influences or other bad things. One can equally expose someone to the arts and other good things.

But there's a stand-alone sense of expose that may be relevant: "exposing oneself" without a reference to what has an explicit meaning, that is revealing a part of the body that (by law) must not be revealed. This sense seems to fit in with the list.

Jongseong Park said,

January 4, 2015 @ 2:49 pm

I have to say that the first thing that comes to mind when I hear about "exposing a minor" is exposure to the elements—we talk of people dying of exposure without specifying to what (for some reason I have images in my mind of Inca children ritually abandoned to die in the mountains). But I would prefer legal language to be more explicit than that.

Joe said,

January 4, 2015 @ 3:05 pm

I don't think the "Greek" reading is all that implausible, if we can think of situations other than abandoning infants to their deaths. I can certainly imagine some sadistic parent, teacher, or guardian punishing a child by making them spent a certain amount of time outside during a harsh South Dakotian winter. Exposing to harm is certainly an idiom, but that kind of general catch-all I would expect as the final element in the coordination, not in the middle.

Simon Spero said,

January 4, 2015 @ 3:45 pm

From the session laws for 1903:

Alan Gunn said,

January 4, 2015 @ 3:48 pm

In a case like this it shouldn't matter what "exposes" by itself means. The legislature could easily have made what they had in mind clear. What they said isn't clear, and people shouldn't go to jail for violated a statute that could have had a clearer meaning, but doesn't. The issue is, or should be, whether the language clearly applies to the conduct in question. If it doesn't, why should we care about what meaning is best?

Tom O. said,

January 4, 2015 @ 4:15 pm

Here's a statute from Michigan that uses the word "expose" without a to-phrase to mean abandon: "Except as provided in subsection (3), a father or mother of a child under the age of 6 years, or another individual, who exposes the child in any street, field, house, or other place, with intent to injure or wholly to abandon the child, is guilty of a felony, punishable by imprisonment for not more than 10 years." MCL 750.135(1). The language tracks back to "section 31 of Ch. 153 of R.S. 1846, being CL 1857, § 5741."

The 1846 statute was interpreted in Shannon v People, 5 Mich 71 (1858) [Google Books link]. The interpretation starts at the bottom of page 89. The Michigan Supreme Court notes that the Michigan statute was copied from the New York Revised Statutes, and that the term "expose" was not a legal term of art. After reviewing various definitions, the court seems to adopt the "leaving or abandoning" definition. (Page 92.)

chips mackinolty said,

January 4, 2015 @ 4:29 pm

With respect to case law and its practitioners, the English language changes, so the term "expose" has moved on in recent years from ancient Greek history, let alone a 1903 statute. There is growing evidence that children exposed to domestic and communal violence, even if not direct victims of, say, assault, can be damaged and traumatised by those witnessed events. In a not inconsiderable number of research projects, being exposed to such violent behaviours may well "normalise" them from the perspective of the kids, and some researchers suggest this leads to intergenerational violent behaviour.

That courts allow the broadening, nuancing and/or redefining of words in statutes is not surprising (though courts are cautiously slow to do so); nor that new legislation reflects these changes in meaning.

Ray Girvan said,

January 4, 2015 @ 5:29 pm

Out of interest, the OED has one definition of "expose" that fits well the legal examples given. It looks to me like an archaic definition – meaning "to imperil" – that has managed to stay as a fossil in legal texts.

Lazar said,

January 4, 2015 @ 5:31 pm

I'm with Volokh: without a to– phrase, the "exposure to the elements" definition is the only one that presents itself in my mind.

@chips mackinolty: What you say about exposure to violence is true, but for me at least, that's just not a comprehensible parsing of the word "expose" when it's unaccompanied by a prepositional phrase. As Dan observes, you could just as well say that it means exposing them to art or anything else.

Bloix said,

January 4, 2015 @ 5:39 pm

response to chiips mackinolty=

This is precisely the opposite of the constitutional requirements for criminal statutes. Judges do not get to decide the "broadening, nuancing and/or redefining" the words of statutes whose application quite frequently ruins the lives of the people they are applied to. Before a person can be sent to prison for years and fined into penury, a court must find that the "plain meaning" of the statute being used to do these things permits them. If the statute is ambiguous, it is supposed to be decided in favor of the defendant. There's no room for "nuancing" in the interpretation of criminal statutes.

If there's a reason to think that the world would be a better place if there were a crime of exposing children to domestic violence, that's what the legislature is for. A judge has no business deciding that a criminal statute making it illegal to abandon a child to the elements (intended to lead to the child's death) should be applied to a spouse who hits his or her spouse (an act not intended to lead to anyone's death and certainly not the child's), or to driving off the road with children in the car.

This man will spend five years in prison although he hurt no one and had no intent to hurt anyone. If the children in car were his, they will be deprived of a father, and they likely will grow up in poverty. This is not broadening or nuancing – it's plain misreading. It's the usual over the top tough-on-crime attitude of judges who face right-wing electorates and are interested in one thing only – not making rulings that could be used in TV attack ads against them.

Eugene Volokh said,

January 4, 2015 @ 6:44 pm

I'm delighted that my post drew Language Log's interest — Language Log is one of the few blogs I read each day. (Indeed, I've set up my Microsoft Outlook to automatically deliver each post to my Inbox shortly after it makes its way into the RSS feed.)

As you might gather, I tend to agree on this with Jongseong Park (and not just because of the common link between Koreans and Jews), Joe, and Lazar, and disagree with chips mackinolty. Chips, might I ask you a variant of the question with which I ended my post? Here it is:

Say that you see an e-mail from someone saying, "John should be prosecuted — he exposed his children."

Someone asks John, "Interesting — what exactly happened?"

"Just what I said, he exposed his children — he let them see him beating up his wife Mary."

Would you suspect that your correspondent is not an experienced English speaker?

Nathan said,

January 4, 2015 @ 7:35 pm

In our modern age, if I see child exposure in a list between child abuse and child torture, I'll immediately think they mean indecent exposure of the child, probably through online exploitation – exposure to the elements wouldn't occur to me in that context, although the discussion that follows (Michigan statute, etc.) really makes the case for it.

Nathan Myers said,

January 4, 2015 @ 8:12 pm

It makes me wonder if a charge of "reckless endangerment" (itself an unusually wonderful description of misbehavior) is toothless enough in that Dakota (as in most places?) that the prosecution was obliged to go out on a limb with this charge. Is recklessly endangering one's own offspring worse than of strangers, justifying adding it to the child-abuse statute? I am not sure. Strangers usually would not be so regularly exposed to such recklessness.

Dave K said,

January 4, 2015 @ 8:44 pm

I followed the link in Prof Volokh's article to the text of the decision. Here's the relevant part:

"The words the legislature used are presumed to convey their ordinary, popular meaning, unless the context or the legislature's apparent intention justifies departure from the ordinary meaning." State v. Big Head, 363 N.W.2d 556, 559 (S.D. 1985). "Expose" is, inter alia, defined in The American Heritage College Dictionary 483 (3d ed. 1993), as "[t]o subject to needless risk."

My copy of the AHD lists this definition as 4(b) and gives as an example "an officer who exposed his troops to enemy gunfire". Of course, this example could be used in a case where the exposure was unavoidable as well. I'm not a lawyer but it does seem that the court was really stretching for a way to uphold the statute.

Mark Mandel said,

January 4, 2015 @ 10:15 pm

Bloix said: “This man will spend five years in prison although he hurt no one and had no intent to hurt anyone.”

Drunken driving and reckless endangerment (e.g., swinging a loaded gun around when you're not alone) are dangerous activities. They are punishable offenses even if no one is hurt and there was no intent to hurt anyone. How can driving at 112 mph, "weaving all over the road and going into the ditch or median with all four tires", with a blood alcohol level of 0.131 and four small children in the car possibly be excused?

Bob Ladd said,

January 5, 2015 @ 2:10 am

For fans of recreational etymology, there's supporting evidence from Italian for Prof. Volokh's interpretation of expose in this context. The common Italian surname Esposito means, literally, 'exposed', and was traditionally given to foundlings – babies abandoned, usually at a church, often by unmarried mothers. Up until the mid-19th century the practice was widespread, and at some churches special provisions were made so that babies could be abandoned anonymously and then fostered or adopted. If you can read Italian, this Wikipedia link gives a lot more detail. (The alleged English version of the same article is not relevant, but there's a very brief English summary here instead.) So I find it convincing that this kind of abandonment is what the South Dakota lawmakers in 1903 were talking about.

Incidentally, in Italian the name is pronounced esPOsito, not espoSIto as in North America.

Nathan Myers said,

January 5, 2015 @ 3:02 am

No relation, BTW, AFAIK.

American Heritage says it, I believe it, that settles it.

chips mackinolty said,

January 5, 2015 @ 3:07 am

@ eugene volokh. I'm not sure I would think the correspondent was or was not an experienced English speaker. The email exchange you cite explains fully what the nature of the exposure was.

@ Dave K, that was precisely my point. Language, even as interpreted by the courts, changes. As you say: "The words the legislature used are presumed to convey their ordinary, popular meaning, unless the context or the legislature's apparent intention justifies departure from the ordinary meaning." This is commonplace in modern legislation and interpretation, including in the criminal law, in Australia at least–though @Bloix suggests it is different in the US.

Alon said,

January 5, 2015 @ 8:08 am

@Bob Ladd:

the same is true in Spanish, where the Latinate form expósito is used in preference to the semi-Latinate expuesto or the properly patrimonial espuesto.

GH said,

January 5, 2015 @ 8:39 am

@chips

Yes, language changes, but does that mean that our interpretation of laws made when a certain word meant a different thing should simply adopt the newer meaning?

If the primary meaning of "slay" becomes "make someone laugh" (as in "You slay me!"), prosecutors should be free to apply any old law on the books that forbid slayings against comedians?

Besides, the argument here is that "exposing" somebody, without an indirect object (or one clearly implied from context) which that person is exposed to, has no "ordinary, popular meaning" (unless it's the "indecent exposure" one). All the dictionary definitions use examples with indirect objects, and no argument so far has made a plausible case that a sentence without it is idiomatic English.

GH said,

January 5, 2015 @ 9:01 am

Let me amend that slightly: "To expose someone" without an indirect object does have at least one ordinary, popular meaning: to expose that person as a fraud or for being guilty of something. Obviously that doesn't make sense in this context.

If we rely on dictionaries, Collins lists senses that require a "to" and ones that don't. The one that best matches the proposed interpretation does:

Simon Spero said,

January 5, 2015 @ 10:18 am

A good case for the use of contemporary dictionaries can be found in Barnett (1999). He articulates well the argument for the use of the original public understanding as the base for determining the meaning of a statute or written constitution. Subjective intent is not accessible; allowing changes in language over time to rewrite laws by implicature, not a legislature has dire, chronic consequences for the rule of law.

Barnett, Randy E., "An Originalism for Nonoriginalists" (1999). Georgetown Law Faculty Publications and Other Works. Paper 1234.

http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1234

Jerry Friedman said,

January 5, 2015 @ 11:08 am

I wonder whether South Dakota has a law against reckless endangerment. This consent order for the suspension of a South Dakota nurse's license says she drove under the influence with her child in the car and was charged with reckless endangerment of the child. Unfortunately it doesn't say whether she was in S.D. at the time. But if S.D. does have a reckless endangerment law, it seems to me that's what Myers should have been charged with (along with DUI and why not reckless driving?), not the vague "expose" charge.

KeithB said,

January 5, 2015 @ 11:17 am

Totally a guess here, but could this have been aimed at Native Americans? Could they have had a practice of abandoning unwanted infants – or could the white majority perceive that there was such a practice?

DW said,

January 5, 2015 @ 11:28 am

Searching on-line databases from the period in question, I think one can find a number of instances of the "expose" in question.

For example, searching Google Books for the phrase "exposed the child" turns up (in addition to things like "exposed the child to danger" etc.) a number of references to legal proceedings against those who had "exposed" children [without "to"] — i.e., abandoned children outdoors, refused to provide shelter for children, etc. I see a "Law Journal" item from 1871 explicitly addressing the question of the scope of the expression "abandoned and exposed the child".

I see a few pertinent examples in newspaper archives ca. 1900 also.

D.O. said,

January 5, 2015 @ 11:45 am

I have a comment/question on a completely tangential matter. Volokh Conspiracy (for which Prof. Volokh is the eponym) indeed is published (is this the word?) by the Washington Post. But Washington Post is also a printed newspaper, which has a parallel website. Is it correct then to refer to a post by Prof. Volokh through a reference to Washington Post?

J. W. Brewer said,

January 5, 2015 @ 2:01 pm

It is a view commonly held by cynics of the legislative process that any legislation with a first name in it (e.g. "Sally's Law," "Jimmy's Law") etc is probably bad public policy, because it is highly likely to be an emotion-driven overreaction to a single well-publicized incident that tugged on the heartstrings of the media and general public (usually involving the death of or other injury to the namesake). Without taking a position on whether http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leandra%27s_Law is fairly subject to that criticism or is a counterexample, its enacement highlights the fact that here in New York until quite recently the existing criminal statutes did not, fairly read, impose nearly as severe a penalty as a certain segment of public/media opinion thought appropriate on people who drove, while intoxicated, a vehicle with children as passengers. If we (imho plausibly) assume the situation was the same in South Dakota, New York's solution of passing a new law with more severe penalties for that specific scenario is less problematic than the alternative of creative reinterpretation by the prosecutors of an old law that doesn't fit the situation very well.

MrFnortner said,

January 6, 2015 @ 6:04 pm

I agree with Bliox that the driver "hurt no one and had no intent to hurt anyone" and that, accordingly, no crime was committed. Statutes at every level of government have mushroomed to cover far too much behavior that does not cause harm to person or property. A law against endangerment is typical of laws that criminalize society's anxieties, apprehensions, fears and suspicions. This is not a matter for Language Log, but I felt it needed to be said.

Nathan Myers said,

January 7, 2015 @ 4:33 am

Thank you for revealing your true colors. I will be sure not to forget.

It is true that Americans have long considered contempt for the lives of strangers a founding principle when profits, comfort, or minor convenience might otherwise be at risk, so chafing at the rare exception is understandable. I don't doubt that the inconsistency will be corrected in due course.

J. W. Brewer said,

January 7, 2015 @ 1:08 pm

http://www.nhtsa.gov/people/injury/enforce/ChildrenAndCars/pages/CriminalLiability.htm (about 10 years old and very much lacking a neutral POV, so discount as appropriate) states that contrary to Mr. Myers' general claims about "Americans," over 2/3 of the states in the country have special provisions in their DWI laws providing for greater penalties when there were child passengers in the vehicle, and also notes that attempts in states w/o such provisions to use more general statutes about child abuse or neglect to fill the gap have met with mixed results. (And indeed I don't think there are any states out there anymore with a "no harm no foul" default approach to drunk driving even w/o such passengers — it has probably become the paradigm instance of behavior that is viewed as sufficiently per se dangerous that it gets punished whether or not harm actually ensues in the particular case — the question is then simply one of how severe the punishment should be under a given set of circumstances.)

I assume S.D. is one of the minority of states w/o a more specific provision, and so the interesting question is that posed by Jerry Friedman of whether the S.D. criminal laws provide any alternative and less clumsy gap-filler, such as a reckless endangerment statute. But even if this guy avoided getting off lightly it would probably be desirable for the S.D. legislature to consider a more specifically-focused provision (looking at the various models available from other states) so that they can make a more focused and conscious decision as to how much incremental punishment they think the particular circumstance of child passengers in the vehicle (in a situation where they were not in fact injured despite being put at serious risk of such injury) merits.

The perhaps-strained language parallel is that American criminal law comes in 50 different single-state "dialects" (w/o getting into federal crimes, territories, etc.), so divergences can and do arise, some dialects innovate to deal with new topics or changes in culture or mores, and sometimes those innovations get copied and sometimes they don't.

J. W. Brewer said,

January 7, 2015 @ 1:21 pm

FWIW as a matter of linguistic history, per the google books corpus "reckless endangerment" seems only to have become a common fixed phrase in various regional dialects of AmEng criminal-law jargon starting in the 1960's, because as a specific label for a specific offense it appears to have been an innovation of the Model Penal Code (finalized by a panel of the Great and Good in 1962 with the hope that state legislatures would either adopt it wholesale or take it as a reputable source of raw material for more piecemeal reform of their local dialects). The MPC reflects a certain rationalistic/technocratic/ameliorist approach to criminal law policy that already seemed antiquated when I was a first year law student in 1989 and the country had post-1962 gone through several decades of Hobbesian post-Enlightenment chaos. What I don't know is to what extent reckless endangerment was simply a new standardized label for conduct that was generally already treated as criminal but categorized more variously (and with inconsistencies as to the exact scope of the offense, not merely its label) or whether it sought to impose criminal liability for conduct that had for the most part not previously been criminal.

Ted said,

January 7, 2015 @ 10:38 pm

I feel compelled to point out that Alan Gunn and Bloix misstate the constitutional standard (and MrFnortner and JWB may implicitly be making the same error, although that is not necessarily the case from their posts).

The constitutional provisions relevant in a vagueness challenge to a criminal statute are the Ex Post Facto Clause in Article I, Section 10, and the due process clause of the 14th Amendment (i.e., the much-maligned "substantive due process"). In either case, the relevant inquiry is whether a reasonable person would have understood that the conduct that is the basis for the conviction is prohibited by the statute in question.

The fact that a statute "could have had a clearer meaning but doesn't" is irrelevant, as long as it's reasonably clear that the conduct is prohibited. And, pace Bloix, courts look to a variety of sources of law and interpretation to decide whether our hypothetical reasonable person was on notice, not merely the plain language of the statute. (Viz. the many decisions upholding laws prohibiting "the crime against nature," and other suchlike euphemisms.)

All that said, I agree with the unindicted Conspirator that "expose," without more, should generally be read as "expose to the elements," as GH and Jongseong Park suggest, and that the decision is therefore poorly reasoned, though perhaps (by definition) not incorrect as a statement of South Dakota law. The court would have done far better to have grounded its ruling on the proposition that reckless driving under the influence, in such circumstances and to such an extent, constitutes a form of abuse.

Steve T said,

January 8, 2015 @ 1:10 pm

Here's a contemporary use of "expose" in the archaic sense, a conversation between Sam and Craster in Martin, A Storm of Swords (p. 452):

"My son. My blood. You think I'd give him to you crows?"

"I only thought . . ." You have no sons, you expose them, Gilly said as much, you leave them in the woods, that's why you have only wives here, and daughters who grow up to be wives.

Bloix said,

January 13, 2015 @ 2:03 pm

Not that anyone is still here, but:

MrFnortner said that he agreed with my view that "no crime was committed." I didn't say that. I said that the crime of exposing a child had not been committed. Driving drunk is a crime. But it's not the crime of exposing a child.

Bloix said,

January 13, 2015 @ 2:19 pm

And to follow on to Steve T:

From The Winter's Tale, in which King Leontes, believing his wife's newborn daughter is illegitimate, instructs a retainer to take the infant and abandon it somewhere far away. He sails to the Bohemian coast (!) and leaves it there, but he is killed (by a bear!) and his ship sinks, while the baby is saved by a shepherd. The events are later recounted, and summed up as follows:

"all the instruments which aided to expose the child were

even then lost when it was found."