Dynamic Philology

« previous post | next post »

After this work, George Kingsley Zipf seems to have turned his attention towards issues generally covered in fields such as sociology and psychology: National unity and disunity: The nation as a bio-social organism (1941), "The P1 P2/D Hypothesis: On the Intercity Movement of Persons" (1946), and Human behavior and the principle of least effort: An introduction to human ecology (1949).

A .pdf of the whole 1935 book is here, all 336 pages of it — but you might want to start with the (22 pages of the) Preface and Introduction. The Introduction begins like this:

DYNAMIC PHILOLOGY has the ultimate goal of bringing the study of language more· into line with the exact sciences. To this end it views speech-production as a natural psychological and biological phenomenon to be investigated in the objective spirit of the exact sciences from which its methods have been taken. Our chief method of procedure is the application of statistical principles to the observable phenomena of the stream of speech.

In this introductory study our primary aim is the observation, measurement, and, as far as it is possible, the formulation into tentative laws of the underlying forces which impel and direct linguistic expression. Our first interest will be in the relationship which exists between the form of the various speech-elements and their behavior, in so far as this relationship is revealed statistically. The findings which result from this initial interest may be viewed as dynamic laws of speech with general applicability, though they are offered, of course, subject to future corrective experimentation. These dynamic laws can presumably be similarly demonstrated from the material of any known language.

Our second interest will be to relate the above dynamic laws with the familiar phenomena of meaning and emotional intensity which have generally proved elusive to direct quantitative analysis. The findings resulting from this second phase of our investigation may be taken only as inferential conclusions; their validity can be apprehended against the general statistical background of the dynamic laws, yet the conclusions themselves can probably never be established numerically because of the nature of the phenomena involved.

The uptake for this book among linguists was far from entirely positive, as illustrated by this passage from Martin Joos's 1936 review in Language.

In the present volume Zipf embraces the whole range of linguistic study and phenomena, from phonemes to 'the stream of speech and its relation to the totality of behavior'. Apparently nothing remains untouched within that range, and the treatment almost uniformly evidences a belief that the author has attained valid formulations. Further, the book is subtitled 'An Introduction to Dynamic Philology', and to judge from the text this means a comprehensive survey of an established science written by an adept. We may therefore take the book for a complete though perhaps not the definitive presentation of Zipf's doctrine, and consequently believe that this is a proper time and occasion to attempt a critique of that doctrine, of its substantiation, and of its application.

The thesis, very briefly stated, is that the key to the explanation of all synchronic and diachronic language-phenomena has been found in a statistically established tendency to maintain equilibrium between size and frequency. Previous critics found the conclusions rash and largely improbable; they placed the blame partly on the introduction of a new technique into linguistic study. If they conceived an unjustly harsh opinion of statistical method in linguistics, the mistake was a natural one, for there was no one to warn them where statistics left off and explanation began except Zipf himself. As the matter now stands, neither the usefulness of statistical method in linguistics nor the value of Zipf's daring and ingenious explanations can be properly appraised, for they have not yet been separated. The separation and the separate appraisals will be the subject of this paper.

For a more recent (and more generally positive) appraisal, see Charles Yang, "Who's afraid of George Kingsley Zipf? Or: Do children and chimps have language?", Significance 2013.

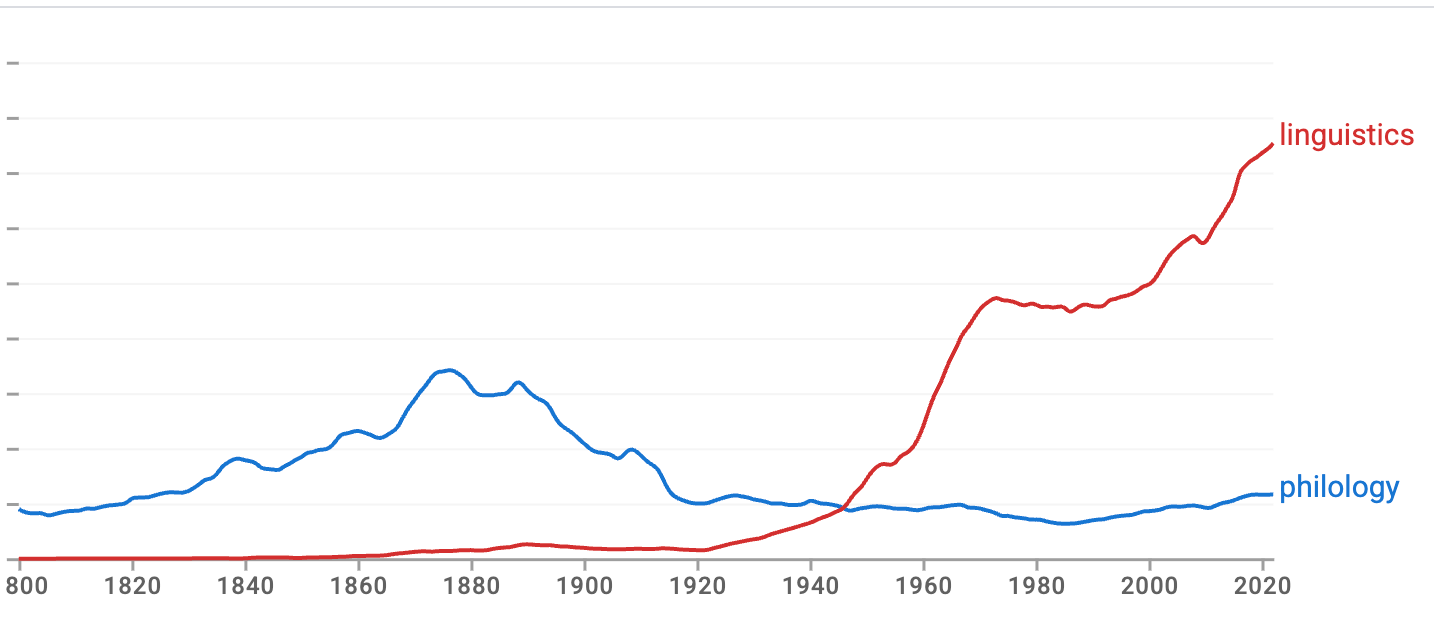

As background for the use of "philology" in Zipf's subtitle, a Google Books Ngrams plot shows that in 1935 "philology" had fallen from its peak in 1875, but "linguistics" was just starting its rise:

There's much more to say, about methodology as well as terminology and personalities, but that's enough for now.

Jean Taylor said,

May 25, 2025 @ 12:44 pm

Relate to Norwegian linguistics researcher Margaret Magnus,PhD. Computer statistical analysis of word sound with meaning: Gods of the Word.

Olaf Zimmermann said,

May 26, 2025 @ 3:58 am

1870s: That is the time when modern linguistics, sociology, and psychology began in earnest. Must have been unsettling for some, whence Nietzsche, a philologist, has been mischaracterized as a philosopher ever since.

JPL said,

May 27, 2025 @ 8:39 pm

@OP: "Our second interest will be to relate the above dynamic laws with the familiar phenomena of meaning and emotional intensity which have generally proved elusive to direct quantitative analysis. [….] the conclusions themselves [of this second phase of interest] can probably never be established numerically because of the nature of the phenomena involved." (Zipf)

Did Zipf seriously pursue this "second phase" of investigations, and, if so, how far did he get, what were the results? He seems to have chosen to pursue the kind of phenomena that were amenable to a statistical method of analysis and explanation, i.e., the observable physical phenomena, and seems to be pessimistic about the possibility of any significant results in this "second" area because the phenomena in question "can never be established numerically". But making a distinction between these two "phases" indicates that Zipf recognizes that, as a distinctive human phenomenon, use of language involves something more significant than just people making funny noises; why are they doing that, and what kind of a thing is this "further significance", and how is it possible? I think naively we all look at this phenomenon called "language" as an interactive activity involving human individuals pursuing happiness and engaging somehow with their understanding of their world. One question that has always puzzled me is, why hasn't the field of linguistics pursued a full empirical understanding of this "further significance"?

I know next to nothing about George Zipf, except that there is something called "Zipf's Law", of which I only have a vague idea about what it is. I'm sure you have good reasons for why we should be interested in Zipf's ideas in relation to the discipline of linguistics, but I'm not sure what they might be. However, given the above observations, Zipf's statement, "DYNAMIC PHILOLOGY has the ultimate goal of bringing the study of language more into line with the exact sciences." and Joos's statement that, "[Zipf's] thesis, very briefly stated, is that the key to the explanation of all synchronic and diachronic language-phenomena has been found in a statistically established tendency to maintain equilibrium between size and frequency." don't seem to bode well for success in any comprehensive study of language. Because, when you say "language", what exactly are you talking about? Are not the "familiar phenomena of meaning " which are the subject of your "second phase" included in what you are calling "human language"? Don't you want to talk of two "aspects" of the language phenomenon here?

JPL said,

May 27, 2025 @ 9:17 pm

Something still bothering me about what I just wrote above; I guess I must beg your indulgence.

Zipf seems to be taking himself as an empirical scientist, and, like the other creators of modern general linguistics, is doing this in a context dominated by Machean phenomenalism and related trends, such as behaviourism, and this atmosphere continued up through the period of Chomsky’s dominance. Even though he had decisively refuted Skinner’s behaviourism, Chomsky, whose approach to language seems to have been influenced by Carnap and Hilbertian formalism, still took an approach that considered the relevant objects of study and explanation to be the perceivable shapes, their objective patterns of occurrence and how the logical rules that apparently governed these were learned, or rather how they unfolded. So he joined the general consensus of linguists that seemed reluctant or afraid to tackle head-on the problem of “meaning”. When he disparaged attempts to understand this "further significance", however, he took these attempts to be mainly, and necessarily, carried out by the field of psychology, and his disappointment with psych attempts was perhaps understandable. The other main approach that has been taken to the study of the "further significance" has been model- theoretic semantics, but this approach belongs to the study of formal languages, whose methods are not really empirical. But it seems possible that there should be a way of understanding this phenomenon of "further significance" as an empirical problem in a scientific approach, starting from within the field of linguistics, instead of farming it out to psych or formal logic. But whoever tries this would need to give up the persistent habit of doing what Hilary Putnam said mathematicians typically do, namely "pointing to the inscription and thinking the meaning". So what is the current state of the art on this question?