Linguistic Laws

« previous post | next post »

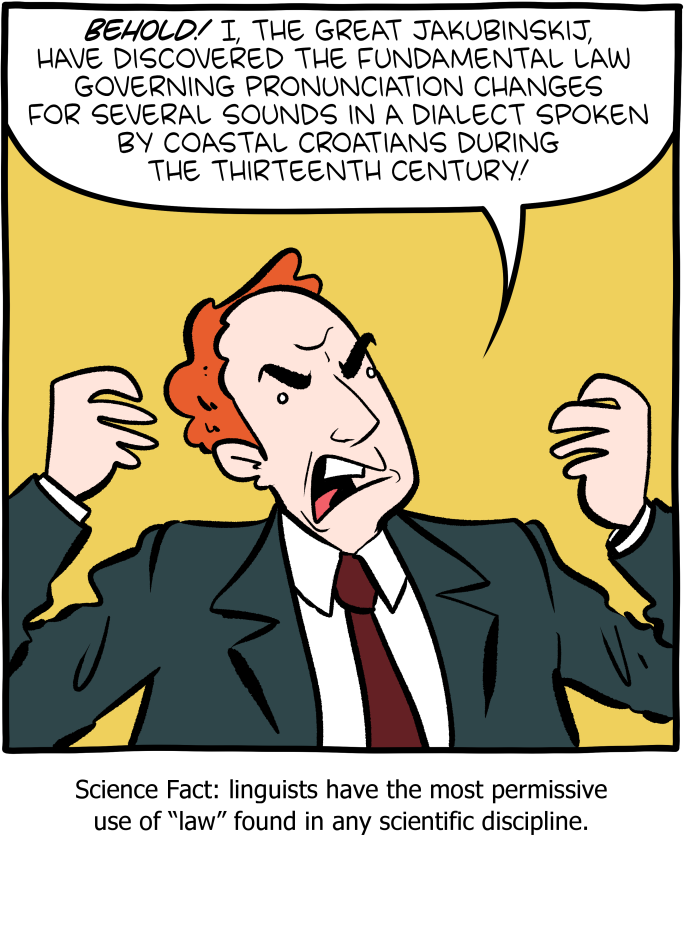

Today's SMBC:

Mouseover title: "This is the greatest Jakubinskij joke in the history of this medium. I believe the Eisners are taking nominations right now."

The aftercomic:

Jakubinskij's Law does actually exist — as Wikipedia explains, "Jakubinskij's law governs the distribution of the mixed Ikavian–Ekavian reflexes of Common Slavic yat phoneme, occurring in the Middle Chakavian area."

Wikipedia does not yet have a page for the law's author, so to get minimal facts about Lav Jakubinski(j) we need to turn to the Hrvatska enciklopedija.

There have been a fair number of scholarly references to Jakubinskij's Law over the years, for example Elena Budovskaja and Peter Houtzagers. "Phonological characteristics of the Čakavian dialect of Kali on the island of Ugljan", Studies in Slavic and General Linguistics 1994:

As can be expected in this part of the Čakavian area, the dialect of Kali is 'i/e-kavian", i.e. it reflects Proto-Slavic jat as either a high or a mid front vowel. More often than not, the reflexes of jat are distributed according to "Jakubinskij's law": mid front before a "hard dental" (d, t, z, s, n, r, l not followed by j or a front vowel) and high front everywhere else.

I believe that we owe to the neogrammarians the idea that regular historical patterns of phonological change should be called "laws": Grimm's Law, Verner's Law, Grassmann's Law, and so on… From Wikipedia's article on Sound Change:

The Neogrammarian linguists of the 19th century introduced the term sound law to refer to rules of regular change, perhaps in imitation of the laws of physics, and the term "law" is still used in referring to specific sound rules that are named after their authors like Grimm's Law, Grassmann's Law etc. Real-world sound changes often admit exceptions, but the expectation of their regularity or absence of exceptions is of great heuristic value by allowing historical linguists to define the notion of regular correspondence by the comparative method.

Contrary to the cartoon's implication, names of the form X's Law have generally not been claimed by the discoverer X, but rather by subsequent investigators who need a term for the pattern in question.

And in recent (and/or less Germanic?) times, linguists have mostly used words like rule, rather than law, to describe regular patterns of sound change in synchronic progress, and have named particular examples with impersonal descriptive phrases, like the Great Vowel Shift (not "Jespersen's Law") or Canadian Raising (not "Joos's Law") or the Northern Cities Shift (not "Labov's Law").

Whatever other socio-cultural issues this terminological difference reflects, it implicitly recognizes the fact that the discovery of these named patterns is almost never the accomplishment of one single person.

Chris Button said,

February 5, 2023 @ 7:46 am

There was a fairly recent attempt to apply the model of “[insert name]’s law” to Sino-Tibeto-Burman linguistics.

On the Sinitic and Burmese sides (I’m not an expert on Tibetan), it didn’t work because the laws were being retroactively applied to concepts that had been uncovered through an amalgam of different scholars’ studies of a related concept, and it also often didn’t go back far enough in the literature to uncover who had actually been exploring some of the concepts first.

In the end, not one of the cleanly named rules for Burmese or Sinitic accurately reflected all the facts. But it was a noble attempt nonetheless, and did provide a useful collection of approaches to the subject in one place.

Oskar Sigvardsson said,

February 5, 2023 @ 8:59 am

Surely an aspect of this is "physics envy" as well, right? Or "physics imitation", maybe. There's Newton's law of gravity, Hooke's law of elasticity, Kepler's law of planetary motion, etc.

I don't think it's unwarranted to have a Grimm's law or whatever. These "laws" tend to be systemic, falsifiable and have predictive power. That seems plenty to be allowed to be called a "law" in the scientific sense to me.

Rodger C said,

February 5, 2023 @ 11:15 am

In this case I suspect physics disdain, or rather physicist's.

[(myl) But see "The life cycle of physicists", 3/21/2012.]

Andrew Taylor said,

February 5, 2023 @ 1:38 pm

> Contrary to the cartoon's implication, names of the form X's Law have generally not been claimed by the discoverer X, but rather by subsequent investigators who need a term for the pattern in question.

Stigler's law of eponymy in action.

J.W. Brewer said,

February 5, 2023 @ 4:13 pm

Isn't the glass-half-full perspective here that at least one internet cartoonist is willing to characterize linguistics as a "scientific discipline"?

David Marjanović said,

February 5, 2023 @ 7:22 pm

It's just historical linguistics being a science like any other. "Law" means "regularity that holds across all observations it could apply to" in scientific usage; laws in this sense are some of the things hypotheses and theories are meant to explain.

Andreas Johansson said,

February 7, 2023 @ 4:23 am

I dunno if I accept that linguistics use "law" in a particularly loose way. Sound change may not be absolutely exceptionless, but it comes closer than various biological "laws" that are really more like recommendations (e.g. Williston's law).

Chris Button said,

February 7, 2023 @ 9:30 am

@ Andreas Johansson

The work on Sino-Tibeto-Burman historical linguistics I mentioned above actually uses the term “conjecture” instead of “law” in some places.

Ultimately, it’s mere semantics since it doesn’t make them any less misapplied or inappropriate, but it does at least somewhat acknowledge the difficulty. In any case, as I said before, it was a noble effort that remains a very useful contribution to the field, albeit largely failed.