"Fading Language"?

« previous post | next post »

People get confused about languages, dialects, registers, and scripts — and when journalists try to help, they often make things worse. For a good recent example, see Mujib Mashal, "Where Romantic Poetry in a Fading Language Draws Stadium Crowds", NYT 12/18/2022:

That more than 300,000 people came to celebrate Urdu poetry during the three-day festival this month in New Delhi was testament to the peculiar reality of the language in India.

For centuries, Urdu was a prominent language of culture and poetry in India, at times promoted by Mughal rulers. Its literature and journalism — often advanced by writers who rebelled against religious dogma — played important roles in the country’s independence struggle against British colonial rule and in the spread of socialist fervor across the subcontinent later in the 20th century.

In more recent decades, the language has faced dual threats from communal politics and the quest for economic prosperity. Urdu is now stigmatized as foreign, the language of India’s archrival, Pakistan. Families increasingly prefer to enroll children in schools that teach English and other Indian languages better suited for the job market.

In "Scripts, Scriptures and Scribes" (1/3/2008) I quoted from Bob King's 2001 paper "The poisonous potency of script: Hindi and Urdu":

Hindi and Urdu are variants of the same language characterized by extreme digraphia: Hindi is written in the Devanagari script from left to right, Urdu in a script derived from a Persian modification of Arabic script written from right to left. High variants of Hindi look to Sanskrit for inspiration and linguistic enrichment, high variants of Urdu to Persian and Arabic. Hindi and Urdu diverge from each other cumulatively, mostly in vocabulary, as one moves from the bazaar to the higher realms, and in their highest — and therefore most artificial — forms the two languages are mutually incomprehensible. The battle between Hindi and Urdu, the graphemic conflict in particular, was a major flash point of Hindu/Muslim animosity before the partition of British India into India and Pakistan in 1947.

[…]

There is a prodigal visual difference between the Devanagari script (also called Nagari) used to write Hindi and the Perso-Arabic script ordinarily used to write Urdu. The Devanagari script of Hindi is"squarish," "chunky," "has edges" — conventional characterizations all — written left to right, with words set off from each other by an overhead horizontal line connected to the graphemes and running from the beginning of the word to its end. The Perso-Arabic script of Urdu is "graceful," "flowing," "has curves," written right to left, with word boundaries marked as much by final forms of consonants as by spaces. The immediate visually iconic associations are: Hindi script = India, South Asia, Hinduism; Urdu script = Middle East, Islam. The graphemic difference between Hindi and Urdu is far more dramatic, for example, than the difference between the Cyrillic script of Serbian and the Roman script of Croatian.

[…]

One can easily imagine a condition of pacific digraphia: people who speak more or less the same language choose for perfectly benevolent reasons to write their language differently; but these people otherwise like each other, get on with one another, live together as amiable neighbors. It is a homey picture, and one wishes it were the norm. It is not. Digraphia is regularly an outer and visible sign of ethnic or religious hatred. Script tolerance, alas, is no more common than tolerance itself. In this too Hindi-Urdu is lamentably all too typical. People have died in India for the Devanagari script of Hindi or the Perso-Arabic script of Urdu. It is rare, except for scholars, for Hindi speakers to learn to read Urdu script or for Urdu speakers to learn to read Devanagari.

But the various common spoken forms of "Hindi" and "Urdu" overlap to such a great extent that the dialogue and song lyrics in Bollywood movies live mostly in the shared space. This has led to some controversy — see e.g. "Language in Bollywood: Hindi or Urdu?".

See also Shoaib Daniyal, "The death of Urdu in India is greatly exaggerated – the language is actually thriving" (scroll.in 6/1/2016), and "From love songs to kurta ads, Urdu is popular with Indians. Why do Hindutva backers hate it so much?" (10/24/2021).

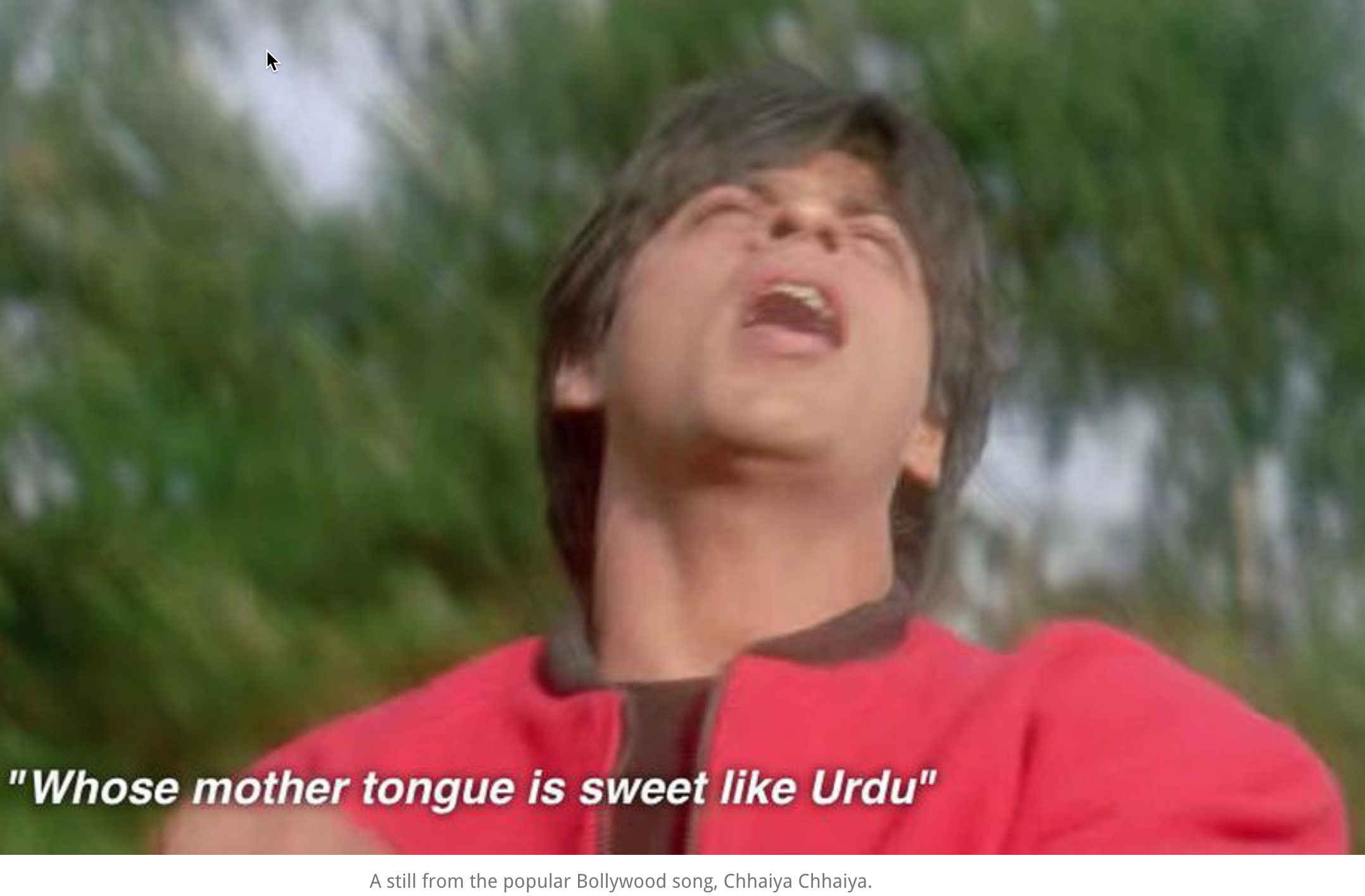

That last reference features this illustration of a line from the movie performance of a popular Bollywood song, "Chaiyya Chaiyya":

The full song, from the 1998 movie Dil Se, can be found in several versions on YouTube, including this one (posted 9 months ago and viewed 23 million times):

The lyrics page on genius.com for this song is presented in Latin script, where the cited couplet (at about 1:27 in the video above, or here with English subtitles) is rendered as

[Pre/Post Chorus: Sukhwinder Singh & Sapna Awasthi]

Wo yaar hai jo khushboo ki tarah

Wo jiski zubaan urdu ki tarah

Genius also offers a "Hindi version", in which the relevant lines are rendered as

[Pre/Post Chorus: Sukhwinder Singh & Sapna Awasthi]

वो यार है जो ख़ुशबू की तरह

जिसकी जुबां उर्दू की तरह

for which Google Translate produces the (semi-mangled) English version

He is the friend who is like the fragrance

whose tongue like urdu

(Readers familiar with Bollywood Urdu/Hindi are invited to offer better translations and explications…)

There does not seem to be a version in Urdu script (whether Nastiliq or Naskh) — which I guess illustrates the meta-sociolinguistic problem we started with.

And for a bit more on Urdu script(s), see "Is the Urdu script on the verge of dying?", 6/29/2014, which references Ali Eteraz's 10/7/2013 "The Death of the Urdu Script", focused on digital Urdu text around the world.

J.W. Brewer said,

December 23, 2022 @ 8:45 am

The overlap of the commonly-spoken variants of "Hindi" and "Urdu" is a common-place observation, but the flip-side of that observation is that the "official" literary-standard versions of Hindi and Urdu are rather more divergent from each other and indeed the respective standards may have to some extent (for cultural/political reasons) evolved in order to maximize that divergence/contrast. So all of the Bollywood stuff is not inconsistent with a narrative that high-falutin' literary-standard Urdu (which presumably would be prescriptively inflicted on students in Indian schools with Urdu as the official language of instruction) is in decline compared to various earlier time periods.

Whether the stadium-filling poetry was primarily composed in the literary-standard register or the Bollywood-demotic register is unknown to me, and I don't have the energy this morning to evade the NYT paywall to see if the full article clarifies that, especially given myl's suggestion that the writer doesn't really understand the situation.

The "Why do Hindutva backers hate it" piece that is also linked to lends up giving a lot of interesting and useful history, although the basic question "why would a nationalist movement dislike a language variety that was developed and promoted by those who collaborated with the foreign occupiers of the country, whether Mughal or British" should not be a particularly puzzling one.

Victor Mair said,

December 23, 2022 @ 9:21 am

"Diglossia and digraphia in Guoyu-Putonghua and in Hindi-Urdu" (1/1/12)

https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=3676

Taylor, Philip said,

December 23, 2022 @ 9:26 am

I managed to capture quite a lot, JWB, before the "you've read your quota" pop-up kicked in — perhaps the following may provide you with further insights :

Philip Anderson said,

December 23, 2022 @ 10:54 am

@J.W. Brewer

A question that refers to “those who collaborated with the foreign occupiers of the country” is far from neutral, and it’s pretty obvious what the questioner’s viewpoint is!

Sally Thomason said,

December 23, 2022 @ 12:15 pm

Muslim families in India who send their children to Hindi-medium schools, where the kids learn to write in Devanagari, often do worry about having traditional Urdu cultural writings being inaccessible to the younger generation. One (indirect?) result of this cultural concern, according to Rizwan Ahmad in his 2007 University of Michigan dissertation Shifting Dunes: Changing Meanings of Urdu in India, is that a few orthographic changes have been made to Devanagari as used in this community to reflect Urdu usage: that is, there's a new Muslim variant of the writing system as used by Indian Muslims.

David Marjanović said,

December 23, 2022 @ 1:09 pm

They're effectively different fonts for the same alphabet, but keep in mind that both are in active use in Serbia, pretty much at random. If you stand in a street in Belgrade or Niš and you can read only one, you're illiterate.

Colin Danby said,

December 23, 2022 @ 3:46 pm

@Brewer: We are communicating right now in a language that's the product of multiple imperial conquests. Your description is unpardonably tendentious. Urdu is spoken by at least 50 million Indians.

Julian said,

December 23, 2022 @ 4:26 pm

'I keep reading it, day and night.

the letter that she never wrote.'

Nice to see that some things transcend ethnic or cultural tensions, anyway.

J.W. Brewer said,

December 23, 2022 @ 8:28 pm

To be clear, I am not necessarily endorsing the Hindutva-enthusiast framing of the historical situation – I'm just saying that a negative view of Urdu flows pretty obviously from that framing of the situation, such that no one should profess to be puzzled by the conclusion that follows from the premises. Maybe the Brits should have stuck with Persian proper as the language of administration for those who couldn't be arsed to learn English, in order to stay more aloof from local tribal rivalries. Or maybe they should have resisted the pressure from various local factions to split up Hindustani (maybe it was still Hindoostanee back then?) into separate soi-disant "languages" with factional affiliations.

J.W. Brewer said,

December 23, 2022 @ 8:34 pm

@David M.: But I take it that there's an asymmetry these days, such that you can be reasonably functional in Croatia w/o being able to read a Cyrillic transliteration of your L1 yet you can't function so well in Serbia (or Montenegro) w/o being able to read a Latinized transliteration of your L1? I am FWIW told that within Montenegro (not a very large place) there is significant regional variation in the ratio of the two scripts to each other in public signage and that that variation correlates fairly well with voting patterns.

Chester Draws said,

December 25, 2022 @ 7:16 pm

Surely if you know a language to fluency you can learn to read it in another alphabet pretty quickly? My wife was able to start reading signs in Cyrillic within days of starting to travel in Eastern Europe, and that was in languages we didn't know.

It takes mere seconds to adjust to a difficult font, as Germans who have to read the ghastly "Fraktur" know.

And the direction of writing is the least of one's worries, as learning to read upside down shows (although the habits of a lifetime about which way to turn the pages of a book are harder to break).

Even minor orthographic differences are simply learned, just as alternative spellings in US and UK cause only minor grief.

So the idea that a person who learns to read in a Hindi writing variant won't be able to operate in an Urdu written environment if they chose to make the change strikes me as unlikely.

Vanya said,

December 25, 2022 @ 8:04 pm

you can't function so well in Serbia (or Montenegro) w/o being able to read a Latinized transliteration of your L1?

My impression working in Vojvodina and Belgrade is that Cyrillic is increasingly peripheral in every day Serbian life. The language of advertising and business is almost always written in Latin script. Cyrillic may be slowly facing the same fate as Fraktur in German – perceived by a younger generation as an old fashioned font with some unpleasant nationalistic overtones.

Barbara Phillips Long said,

December 26, 2022 @ 3:03 am

For more on the politics of language in India, see this article about how languages used by large numbers of Indians are disadvantaged in relation to Hindi, particularly by the current ruling party:

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/dec/25/threat-unity-anger-over-push-make-hindi-national-language-of-india