ytš ḥṭ ḏ lqml śʿ[r w]zqt

« previous post | next post »

Which being translated is "May this tusk root out the lice of the hai[r and the] beard".

You can read all about this object here: Daniel Vainstub et al., "A Canaanite’s Wish to Eradicate Lice on an Inscribed Ivory Comb from Lachish", Jewish Journal of Archaeology 2022. The abstract:

An inscription in early Canaanite script from Lachish, incised on an ivory comb, is presented. The 17 letters, in early pictographic style, form seven words expressing a plea against lice.

Or you can consult Oliver Whang's article in the NYT, "An Ancient People’s Oldest Message: Get Rid of Beard Lice", 11/9/2022.

The subhead: "Archaeologists in Israel unearthed a tiny ivory comb inscribed with the oldest known sentence written in an alphabet that evolved into one we use today."

A small quibble here is that the script in question is technically an abjad, not an alphabet — but "…written in an abjad that evolved into the alphabet we use today" would be inappropriately obscure for NYT readers. And it's common to use terms like "the Hebrew alphabet" or "the Arabic alphabet". Another small quibble is that there are graffiti in (a version of) the proto-Sinaitic script from Egypt, dated (by some) a few hundred years earlier than this marvelous comb. (Apparently the Egyptian inscriptions, apart from the dating uncertainties, are not totally deciphered and may not express full sentences.)

Unsurprisingly, much of the comb's coverage in the mass media is more misleading. Thus the headline for Mark Lungariello's article in the New York Post is "Oldest sentence in history discovered – warning of beard lice almost 4,000 years ago":

The oldest sentence written in the earliest known alphabet has been discovered – carved into an ivory comb which warned about head lice.

It's obvious that "the oldest sentence in history" must have been spoken many tens of thousands of years before any writing systems were invented …

Anyhow, the Vainstub et al. article will give you all of the inscription's details character by character:

The inscription contains 17 tiny letters that vary in width from 1 to 3 mm, engraved on the not-completely-smooth surface of the comb. The letters form seven words that for the first time provide us with a complete reliable sentence in a Canaanite dialect, written in the Canaanite script.

Most of the letters survive to some degree, except for letter 13, which was totally damaged, and letter 14, of which only a few parts remain. The engraver did not maintain alignment of the letters or uniformity of their size. In the first row that he wrote, the letters become progressively smaller and lower. In this row the script runs from right to left, and when the engraver reached the edge of the comb, he turned the comb through 180° and wrote the second row from left to right, in such a way that the rows are arranged “heads on heads”, with the heads of the letters in the middle of the comb and the bases of the letters facing both lines of teeth. When the engraver reached the edge of the comb at the end of the second row, not enough space remained for another letter, and so he engraved it below the last letter of the row. Because of the change of orientation, both rows start on the same side of the comb, unlike in the boustrophedon method.

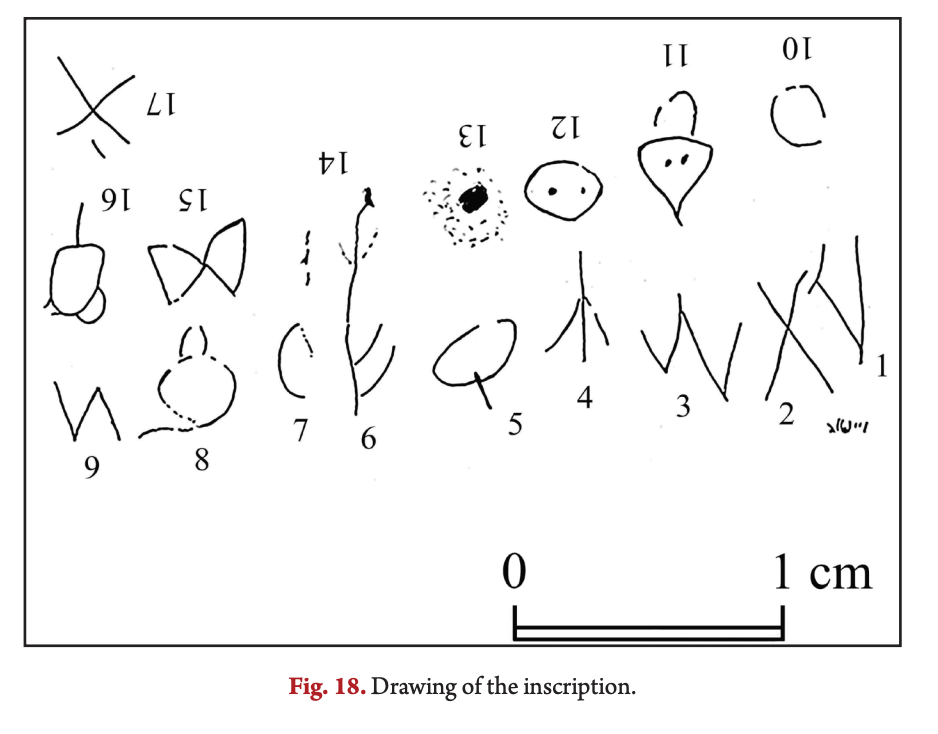

Here's their diagram of the inscription:

They go through the 17 letters in detail, one at a time. What they say about the first one:

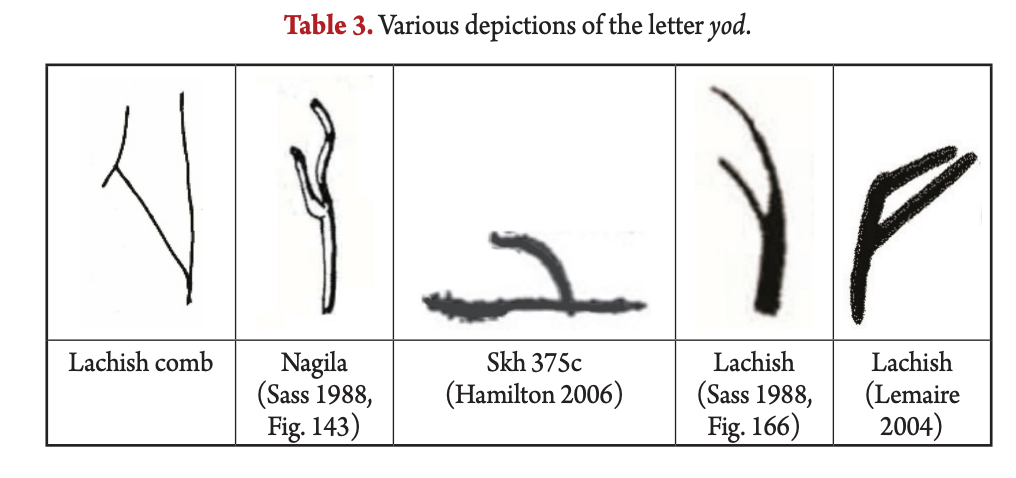

Letter 1. The letter is a standing “curved palm” yod (Hamilton 2006: 108–112) with considerable disproportion between its parts: the thumb, which was most probably engraved first, is longer than would be expected (Table 3). Yods executed in a similar fashion are known from Serabiṭ el-Khadem inscription 375c (Hamilton 2006: 377) and the Tel Nagila sherd (Sass 1988, Figs. 143–144). The stratigraphic dating of the Tel Nagila sherd is not entirely clear; initially it was dated tentatively to the end of the Middle Bronze Age or the beginning of the Late Bronze Age, but this is now controversial (Sass 2005: 159; Finkelstein and Sass 2013: 156).

Read the whole thing!

Yuval said,

November 10, 2022 @ 7:20 am

The co-author from Lipscomb University is truly icing on the cake.

Mark Liberman said,

November 10, 2022 @ 8:03 am

@Yuval: The Lipscomb University Lanier Center of Archaeology is real, though. And so is the cited co-author.

Yuval said,

November 10, 2022 @ 8:30 am

Oh, absolutely, I didn't mean to suggest otherwise, but it's a heck of a coincidence, no?

Peter Grubtal said,

November 10, 2022 @ 9:17 am

Yuval –

it's nominal determinism

Bloix said,

November 10, 2022 @ 9:43 am

English-speaking scholars have been describing the Hebrew script as an alphabet for many centuries (do a google books search for examples from the 1500s) and in Latin texts as the alphabetum hebraicum before that.

Abjad is a word introduced, or perhaps redefined, in 1991 by an American scholar named Peter T. Daniels. It is so rare that it is not in any Merriam Webster online dictionary. Daniels' contention that people should stop describing a script without vowel characters as an alphabet seems to be a distinction of his own invention, and appears to be a matter of contention in his field on both historical and technical grounds.

It's fine for scholars to have a technical language that allows them to communicate specialist concepts among themselves, but the assertion that the Hebrew script is not a an alphabet, even if it were generally accepted among specialists, would be somewhat less accurate as a matter of lay usage than the contention that a tomato is not a vegetable.

Jonathan Smith said,

November 10, 2022 @ 11:53 am

Re: lay usage of alphabet yes to Bloix, though I would be surprised if Daniels (or anyone?) wished the masses to "stop describing a script without vowel characters as an alphabet".

The terms abjad, abugida and relatives, while referencing points on a continuum, are nonetheless useful and widely-used in the study of writing systems. The impression, of which echoes remain in particular on Wikipedia, that there is controversy in the field surrounding these terms and antagonism towards Daniels in particular seems to stem from a vigorous, misguided campaign by a single author who wished to insist that the Semitic, Brahmic, etc., scripts were "not 'abjads' or 'abugidas'" (or "other monsters") but rather syllabaries.

Victor Mair said,

November 10, 2022 @ 1:32 pm

As the author of the chapter on "Modern Chinese writing" in The world's writing systems, eds. Peter T. Daniels and William Bright (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 200-208, I find the exchange between Bloix and Jonathan Smith above to be of considerable interest.

Victor Mair said,

November 10, 2022 @ 1:37 pm

In reading through Daniel Vainstub et al., "A Canaanite’s Wish to Eradicate Lice on an Inscribed Ivory Comb from Lachish", Jewish Journal of Archaeology 2022, the metonymical use of the word "tusk" to refer to the comb fairly leapt off the page.

p. 104, first sentence:

The word חט in Tannaitic sources, spelled חיט in some manuscripts (Bar-Asher 2015: 239–240), signifies a certain type of teeth in animals, and since ḥṭ here refers to the comb made on [recte of] elephant ivory the connection seems inescapable.

Victor Mair said,

November 10, 2022 @ 1:49 pm

ושדר לה סריקותא דמקטלא כלמי

“And he sent to her a comb that kills lice”

(Babylonian Talmud, Niddah 20b)

This function of the Lachish comb is particularly poignant for me since it evokes memories of many of the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age mummies of Eastern Central Asia whose pubic and scalp areas were infested with lice (e.g., the Beauty of Loulan), so much so that archeologists who examined them had a hard time believing these individuals could endure the intense itching that would have been caused by having so many of these tiny beasties inhabiting their body.

That shone a whole new light on why so many of the mummies were buried with fine tooth combs!

Bloix said,

November 10, 2022 @ 3:28 pm

Jonathan Smith – the desire to have a word for the subset of alphabets that have characters for consonants but not for vowels makes sense. The idea that such scripts are not alphabets at all seems incorrect and certainly confusing to lay people.

PS- someone (with credentials, not a nym like me) should contact Merriam Webster and tell them to put abjad in their scrabble dictionary. Four letters and one an eight-pointer! and the initial A and final D – for linking to words on the board! Sure to amaze the other players – maybe attract a challenge!

Peter Grubtal said,

November 10, 2022 @ 3:51 pm

This year's the bicentenary of Champollion presenting his decipherment of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic (there's a wonderful exhibition about it at the British Museum right now, for anyone in London).

The proto-sinaitic alphabet was apparently arrived at by taking Egyptian hieroglyphs which had good pictorial value, and assigning to them the first letter of the corresponding semitic root. Thus hieroglyphs have a symbol representing water (a long zigzag, or saw teeth) which is a word beginning with "m" in common semitic (miya in modern Arabic, I think). The zigzag was shortened, and is still recognisable in our "M", arrived at through proto-sinaitic-> canaanite -> phonecian -> greek -> Latin.

It tickles me to think our letters (or their forms at least) have five thousand years of history behind them.

Rodger C said,

November 10, 2022 @ 4:18 pm

a single author who wished to insist that the Semitic, Brahmic, etc., scripts were "not 'abjads' or 'abugidas'" (or "other monsters") but rather syllabaries

Do you mean I. J. Gelb? I found his book on writing systems fascinating, but I just had to read past the insistence that all writing evolves without exception from logograms to syllabaries to alphabets.

CuConnacht said,

November 10, 2022 @ 6:48 pm

I am reasonably sure that the NY Times reporter was wrong to say that the inscription "warned about head lice." I imagine that the inscription was meant to function as a charm, adding to the power, and probably the price, of the comb. There may also be a bit of contagious magic in the use of the words for "tusk" and "root out": "Just as the elephant rooted things out of the earth with his tusk when alive, so may this root out lice."

wanda said,

November 10, 2022 @ 8:27 pm

@Victor Mair: those combs couldn't have been all that effective if the mummies are still densely infected with lice.

Victor Mair said,

November 10, 2022 @ 9:20 pm

@wanda

Better to comb out some of the buggers than to let them take over completely.

See Daniel Vainstub et al., "A Canaanite’s Wish to Eradicate Lice on an Inscribed Ivory Comb from Lachish", Jewish Journal of Archaeology (2022), p. 83, Fig. 4 for a striking photograph of the Remains of a head louse nymph between the teeth of the Lachish comb.

Cows, horses, and humans are tormented by flies, mosquitoes, and chiggers, but we fight back against them to the best of our ability, don't we?

Victor Mair said,

November 10, 2022 @ 9:23 pm

Combs were also used as important tools in early weaving.

"The Wool Road of Northern Eurasia" (4/12/21)

KeithB said,

November 11, 2022 @ 8:36 am

Wanda:

A dead person can't comb. It could very well be that a lot of the infestation was post-mortem.

Sally Thomason said,

November 11, 2022 @ 10:29 am

@Jonathan Smith: Who was the single author? Gelb's heyday was decades before Daniels published, so it'd be a bit surprising if Gelb himself was actively hostile to Daniels. (…unless he had fanatic followers?) — Not my area, though, so obviously I could be quite wrong about this. I've always thought it was kind of silly to credit the Greeks with inventing the alphabet just because the relevant Semitic writing omitted vowels; the principle of the alphabet is usually given as "one symbol per phoneme", and it seems to me that those Semitic writing systems meet that criterion even if they don't usually have a symbol for EVERY phoneme.

GH said,

November 11, 2022 @ 12:35 pm

I was a little puzzled to see the authors take it for granted that the use of "tooth" or "tusk" for the comb must be in reference to the material, ivory, rather than to (what we call) the teeth of the comb.

Is that assumption grounded in the word clearly being in the singular, or that this analogous extension of meaning for "tooth" does not occur in Semitic, or some other reason? In a paper otherwise so clear and readable to a layperson, it stood out as a logical leap without apparent justification.

Chris Button said,

November 11, 2022 @ 2:26 pm

That complete "axe head" for Zayin is interesting.

languagehat said,

November 11, 2022 @ 4:45 pm

Note that the journal is not the "Jewish Journal of Archaeology" but the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology; the full citation is Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology 2 [2022]: 76-119.

Victor Mair said,

November 11, 2022 @ 5:25 pm

From Zhang He:

Very interesting discovery ineed!

Talking about lice in Central Asian mummies, lice was still a practical problem in the mid-20th century in south Xinjiang. Growing up in Khotan, I witnessed a common scene of a woman killing/squeezing a louse with two thumbnails in the hair of a child, or two women doing it for each other. There was, and still is, a fine comb called bizi 篦子 specially made for combing out lice. It works well to drive out the grown lice, but not well to the eggs. So bizi is not a tool to extinguish lice completely.

I also had personal experience of being infected with lice. Once my mother was on a job assignment away from home for a month (cannot remember exactly how long), my careless father did not pay enough attention to me and my brother. When mother came home, she noticed me scratching body constantly to find out that both me and my brother had lice, she immediately ordered everyone, including my father, to take off all clothes and boiled our clothes in a wash bowl for 30 minutes for each full bowl. That was the only time I got infected. My mother regularly boiled our clothes in the 1960s and 70s. I remember only once that my father had to be shaven bald to kill his lice in the hair after he had weeks of journalistic assignments in the countryside.

The lice problem is not a matter of life and death, but it is such a nuisance that one wants to get rid of it thoroughly.

Victor Mair said,

November 11, 2022 @ 5:27 pm

Women would do the exact same thing in Nepal. Sometimes they would bite the lice between their teeth.

Jonathan Smith said,

November 11, 2022 @ 6:56 pm

@Bloix @Sally Thomason this author/book but was trying to avoid calling anyone out — many have fallen victim to the temptation to rewrite Wikipedia etc. in their own image…

While the utility of Daniels' suggested terminology seems clear, I appreciate that the problem could be dealt with in other ways — if one wants to stay with established terms, not much is wrong with "consonantal alphabet", or if reserving plain "alphabet" for the Greek system feels Eurocentric, then by all means "alphabet" for the Semitic systems and more specific terms elsewhere. Not "West Semitic syllabaries" though please :D

And of course, whatever happens in academic contexts, "alphabet" will continue in its non-technical applications … even Chinese speakers get puzzling questions about the "Chinese alphabet" from time to time, and eventually suss out that they are being asked about the writing system / characters.

Philip Taylor said,

November 12, 2022 @ 3:51 am

Zhang He writes "lice was still a practical problem in the mid-20th century in south Xinjiang" — I believe that the same was true in the United Kingdom, albeit perhaps slightly earlier. My mother (b.≈1913, London/Kent border) told me that in her childhood the school nurse was referred to as "Nitty Nora", one of her primary tasks being to remove lice and nits (head lice eggs) from the hair of children.

Victor Mair said,

November 12, 2022 @ 12:11 pm

@Philip Taylor

"Nitty Nora" — cool!

Meandering medieval and modern merchants and medicine men

When my brothers and sisters and I were students at Osnaburg Elementary / Grade School in the early 50s in Stark County (northeast Ohio), my own Mom had to delouse us from time to time.

She also had to deal with things like impetigo, ringworm, scabies, and pink eye. They were mostly intensely itchy skin conditions caused by tiny insects (chiggers, harvest mites, bush-mites, srub-itch mites, red bugs, berry bugs — these are just some of the names for one type of such insects that cause skin irritation and inflammation — Trombiculidae) and were quite common among the entire student body, though parents and the school nurse did their best to cope with them. The arsenal of treatments included all sorts of salves and ointments, many of which were sold to rural families by the "Watkins Man" (Mr. Hostetler in our area) from his small truck, which also carried foodstuffs, toys, and all sorts of other goodies. I think he came about once a month, maybe less because his territory was large, and his visit was genuine cause for celebration. We children would gather around his truck, its side panels raised open, dancing and jumping and shouting with glee, oohing and aahing.

I believe that the J. R. Watkins company was founded around 1868 and was still very popular when I was in grade school and high school, then it seems to have largely disappeared (temporarily? partially?) (went out of business?) for decades, though I was amazed when I came to Penn in the early 80s to find a staff member using a Watkins salve. When I asked her where she got it, she gave me a phone number in an obscure part of town. I made an appointment to drive to a mysterious house and picked up three tins of Petro-Carbo Salve (with Phenol-Carbolic acid), one of Menthol Camphor Ointment, and a bottle of Panol Linament (with oil of wintergreen, oil of cloves, gum camphor, oils of peppermint and eucalyptus, and safrol). I still have these Watkins products in my medicine chest, and they are still efficacious. Still more recently, I was astounded to see that Watkins soaps have become fashionable in a wide variety of stores and shops, although they are marketed in old-fashioned packaging.

When we had the croup, Mom would rub one of these salves on our chest and cover it with a thick, soft flannel cloth and make us lie still for awhile, whereupon the croup usually cleared up within a day or two. Some of the Watkins products had drawing properties, and people loosely referred to them as "horse salve".

A thousand years ago in China, the equivalent of the Watkins Man would have been these Song Dynaty peddlars (please do click on the link to take a gander at these fantastic paintings of itinerant vendors in medieval China).

If these peripatetics specialized in medicine and curing, they might have been called jiānghú yīshēng 江湖醫生 ("doctors of rivers and lakes" [i.e., "wandering physicians"]). Some people pejoratively refer to them as "quacks", but I think that is to unfairly stigmatize them. In many cases, they provided the only medical care that was available outside of cities and towns, and often illness and disease were cured under their care. As in rural / western America, Japan (e.g., etoki 絵解(き) ["picture explanation"]), and elsewhere, such practitioners would usually combine or specialize in one or more of the following: medicines, treatments, snacks, toys, entertainment, and so forth.

Back to the Watkins Man. If his unguents and herbal preparations in bottles did not solve our various inflictions / infections, Mom and Dad might have to go some distance to a drugstore and get something more modern, scientific, and powerful (though they rarely did that). Some of these things smelled strongly sulferous.

Only if our health were truly in danger would Mom call in the neighbors to pray for us. As a last resort, she would bring in Dr. Davis, the town M.D., or — in extreme circumstances — Mom and Dad would take us to a hospital in the city. Both of the latter options seldom (almost never) happened. Most of the healing in the Mair family was done right in our house.

Bob Ladd said,

November 12, 2022 @ 12:53 pm

Assuming my experience as a parent of early school-age children in the UK at the end of the 20th century was fairly typical (and I have every reason to believe that it was), lice are in no way a curiosity from the olden days, as implied by some of the comments above.

HE ZHANG said,

November 12, 2022 @ 2:26 pm

Testing …

Philip Taylor said,

November 12, 2022 @ 2:29 pm

Victor's discussion of Watkins' medications reminded me of my own former G.P, a wise old Irish doctor called Dr Groom. When (some 50 years ago) my "dhobi itch" (Tinea cruris) refused to yield to the currently available antifungals, he prescribed Whitfield ointment (Benzoic Acid Ointment, Compound, BP), saying that it had worked for him when he was serving in India. And it worked for me, and I still keep a jar to this day, even though modern anti-fungals are now equally effective.

HE ZHANG said,

November 12, 2022 @ 2:43 pm

Hi, Language Loggers:

I finally logged into this log. Thanks to Dr. Victor Mair's transportation of posts in the past, I have been in this log for some time. Now I can post directly here.

About lice, it is nice to know that it has been a common phenomenon all over the globe, in London/Kent, in Ohio.

I'd like to add one more interesting incident in history. In Edgar Snow's interview with Mao Zedong in 1936/7, he noticed Mao scratching the louse bites while they were talking. I could not find exact description online, but remember reading that part long time ago. It was a common thing among the Red Army soldiers.

M said,

November 12, 2022 @ 6:33 pm

See here on the company:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watkins_Incorporated (and the very next

entry in Wikipedia is on the founder himself).

January First-of-May said,

November 13, 2022 @ 6:28 am

Abjad is a word introduced, or perhaps redefined, in 1991 by an American scholar named Peter T. Daniels. It is so rare that it is not in any Merriam Webster online dictionary.

I've been wondering how abjad earned its place in my (ongoing) list of five-letter English words not accepted in Wordle. (Most of the other words on the list are far more obscure, and/or far more blatantly slangy.) Being created in 1991 would do it, I guess.

As far as I'm concerned, an abjad is a kind of alphabet, but an abugida is a kind of syllabary; the status of some Brahmic scripts (and Hangul, for that matter) can be less certain, but you need to be about as much of a pedant to claim that the Ge'ez script is not a syllabary [in its non-abjad version, anyway] as to claim that the Hebrew script is not an alphabet.

Philip Anderson said,

November 13, 2022 @ 12:55 pm

Abjad was added to the OED in March 2009:

https://public.oed.com/updates/new-words-list-march-2009/

But I wouldn’t expect even a highbrow newspaper to use the term, unless discussing the difference between, say, the Hebrew and Greek alphabets.

Bloix said,

November 13, 2022 @ 3:08 pm

Bob Ladd – and parents still use fine-toothed combs to pull the nits out of their children's hair. https://www.cvs.com/shop/cvs-health-lice-removal-combs-and-magnifying-glass-2ct-prodid-1013430

Bloix said,

November 13, 2022 @ 3:11 pm

Philip Anderson –

But it hasn't made it into the Merriam Webster Official Scrabble(TM) Players' Dictionary, which is a loss to the game!

Philip Anderson said,

November 13, 2022 @ 3:57 pm

@Bloix

Nor the Collins Official Scrabble Words used in most other countries. It used to be Chambers Dictionary that was the arbiter when I was young.

Michael Watts said,

November 13, 2022 @ 5:13 pm

Slanginess is not supposed to be disqualifying; Wordle infamously allows "GRRRL".

I'm confused by the putative distinction between abugidas and syllabaries — Ge'ez script is clearly a syllabary in that the form of a character is not predictable by knowing its consonant and vowel. There are obvious visual patterns, but at best that lets you get the sound from the shape of the glyph, not the other way around. And sometimes not event that.

So if Ge'ez script is an example of an abugida, it can only be the case that abugidas are a subset of syllabaries.

I would not hesitate to use "alphabet" to refer to any writing system of any kind, as long as it had conventional glyphs. Purely ad-hoc illustrations would not count.

I've never understood why the term "abjad" was supposed to be useful at all; an abjad is an alphabet that carries incomplete information about the sound of the words written in it. But that describes all alphabets. Why complain that Arabic doesn't indicate vowels, but not complain that French doesn't indicate pitch?

Victor Mair said,

November 13, 2022 @ 7:47 pm

From Elizabeth Wayland Barber:

At the very first working excavation I ever visited, in 1953 in England, they had just found a weaving comb! How prophetic.

You don't need a weaving comb for making ordinary cloth on a big loom–because you use a long beater-bar instead and push everything home at once. But it's VERY useful for band looms, tapestry weaving, pile rug looms, and anywhere else you need to push the weft (or knots) up tight across just a FEW warps at once. So the comb might be an inch wide or 3 or 4 inches wide, as needed.

Philip Anderson said,

November 14, 2022 @ 6:24 am

@Michael Watts

As I understand it, each symbol in a syllabary defines an arbitrary consonant+vowel syllable (where the consonant may be null, to allow words to start with vowels).

But an abugida has symbols for individual consonants and vowels, like a true alphabet, except the vowel symbols are usually written on or in a neighbouring consonant, so they look like one glyph (and are presumably printed as one) – initial vowels may also have standalone symbols, and an absent vowel symbol may indicate an implicit, default vowel.

I agree that abjads and abugidas are merely subtypes of alphabet, perhaps useful jargon for specialists (and quiz addicts), but not essential distinctions in everyday use. The significant step in alphabetic development was taken by Semitic speakers, and both Greek and Indic developments subsequently were just variations to suit their languages. As were adding accents or diacritics to letters or numbers to indicate tones.

As for a syllabary where the vowel is indicated by rotating the consonant, that seems to me to actually be an abugida, because the elements can be analysed separately, even though the vowel is shown by an action not a diacritic.

January First-of-May said,

November 15, 2022 @ 6:52 am

Slanginess is not supposed to be disqualifying; Wordle infamously allows "GRRRL".

The blatantly slangy words on my current list are JANKY, OODLE, SQUEE, UNFUN, and YOINK; I can see an argument against the second, because it's normally used in the (six-letter) plural, but the rest of them are probably just too recent.

Arguably some of the regional words on the list, such as GUMBY ("stupid, esp. of a mountain climber") and DRUNG ("in Newfoundland, a kind of street"), also qualify as slang.

But most of it are technical terms, often directly borrowed from foreign languages, which invites a question on whether they qualify as English words at all. My usual go-to example of this is QIRAN ("an 19th century Persian coin denomination"), but in this audience HANZI would be a better example. (Yes, neither is on Wordle.)

Adrian Morgan said,

November 15, 2022 @ 8:26 pm

There's an interesting interplay here between the broad and narrow senses of the word "history". The claim is technically defensible from the narrow sense of the word, in which "history" is differentiated from "prehistory" and equated it with the presence of written records, but it gains its motive force from the broad sense, as "oldest sentence in writing" would not sound as impressive!

January First-of-May said,

November 17, 2022 @ 2:21 pm

I apologize for possibly misleading the Language Log audience; it turns out that ABJAD (as well as SQUEE and JANKY, but not YOINK or HANZI) were added to the Wordle word list in the August 2022 update. I somehow missed this… probably because there's approximately nothing about it online outside the wordlist GitHub.

(There are reports of a November 2022 update, but I have yet to see an updated word list, so cannot confirm whether any more of my words are in it.)

Miscellany № 97: interrobang archaeology, part 2 – Shady Characters said,

November 21, 2022 @ 5:50 pm

[…] include Hebrew and Arabic.) At least it’s not a syllabary, amirite? Head over to the Guardian and Language Log to learn […]

Miscellany № 97: interrobang archaeology, part 2 – Shady Characters said,

November 21, 2022 @ 5:57 pm

[…] consonants, modern examples of which include Hebrew and Arabic. Head over to the Guardian and Language Log to learn […]