More "I don't know"

« previous post | next post »

We're following up on "Dinosaur Intonation" (8/28/2021) and "Hummed 'I don't know'" (8/29/2021). And today's installment starts with a distinction. There are two largely separate issues:

- Intonational choices (for performances of "I don't know" or any other phrase).

- Various types of articulatory reduction or replacement,

from crisp hyper-articulated performances,

through progressively slurred versions,

to hums, grunts, or even whistled or instrumental imitations.

Homer Simpson's version, from this YouTube clip, lenites the consonants pretty much to extinction, and reduces the second ("don't") vowel as well, going beyond Michael Watt's comment about a friend who spelled it "iono":

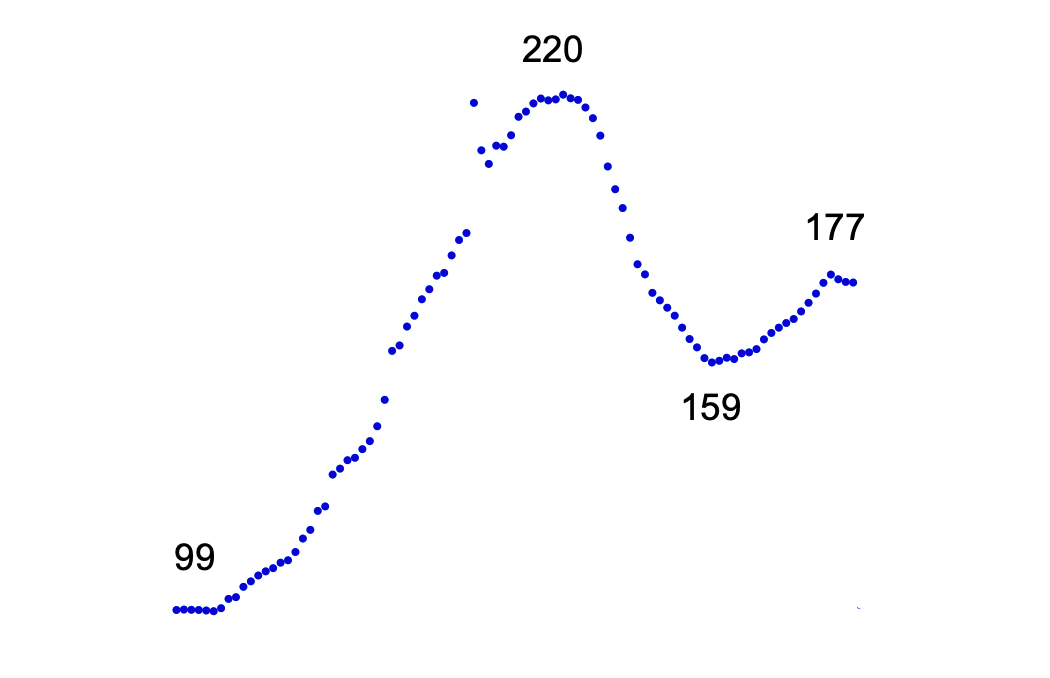

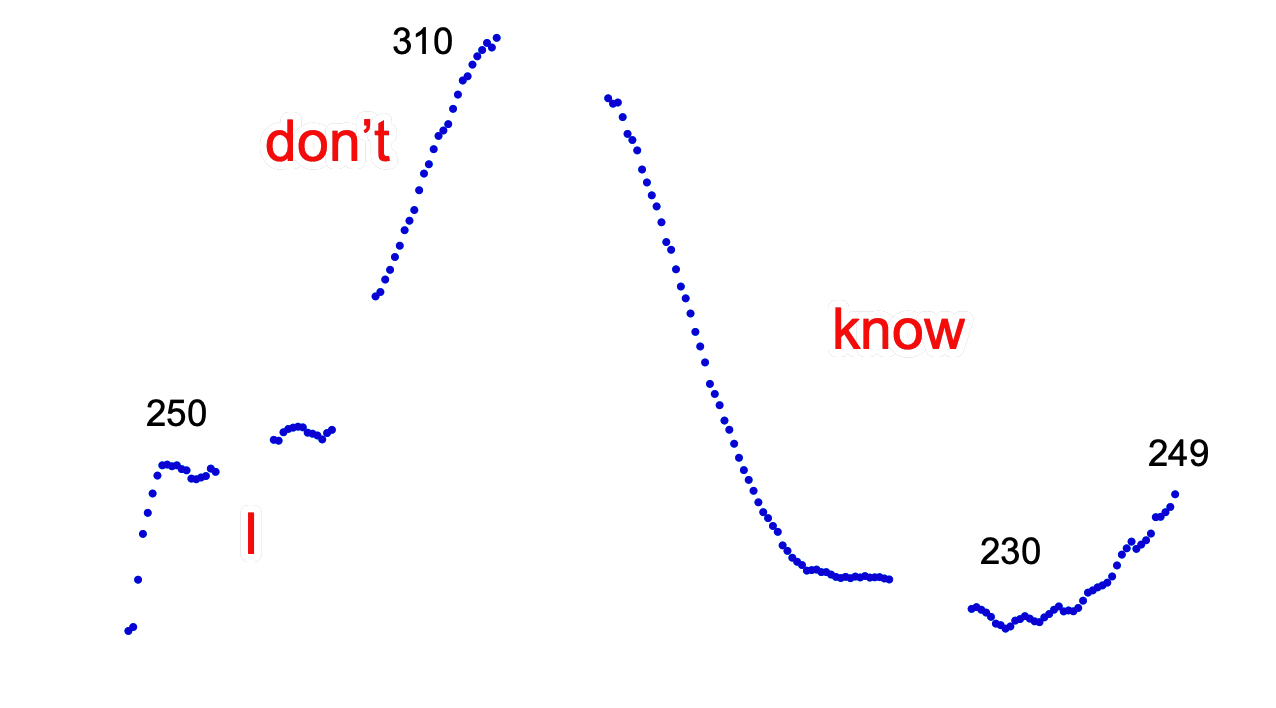

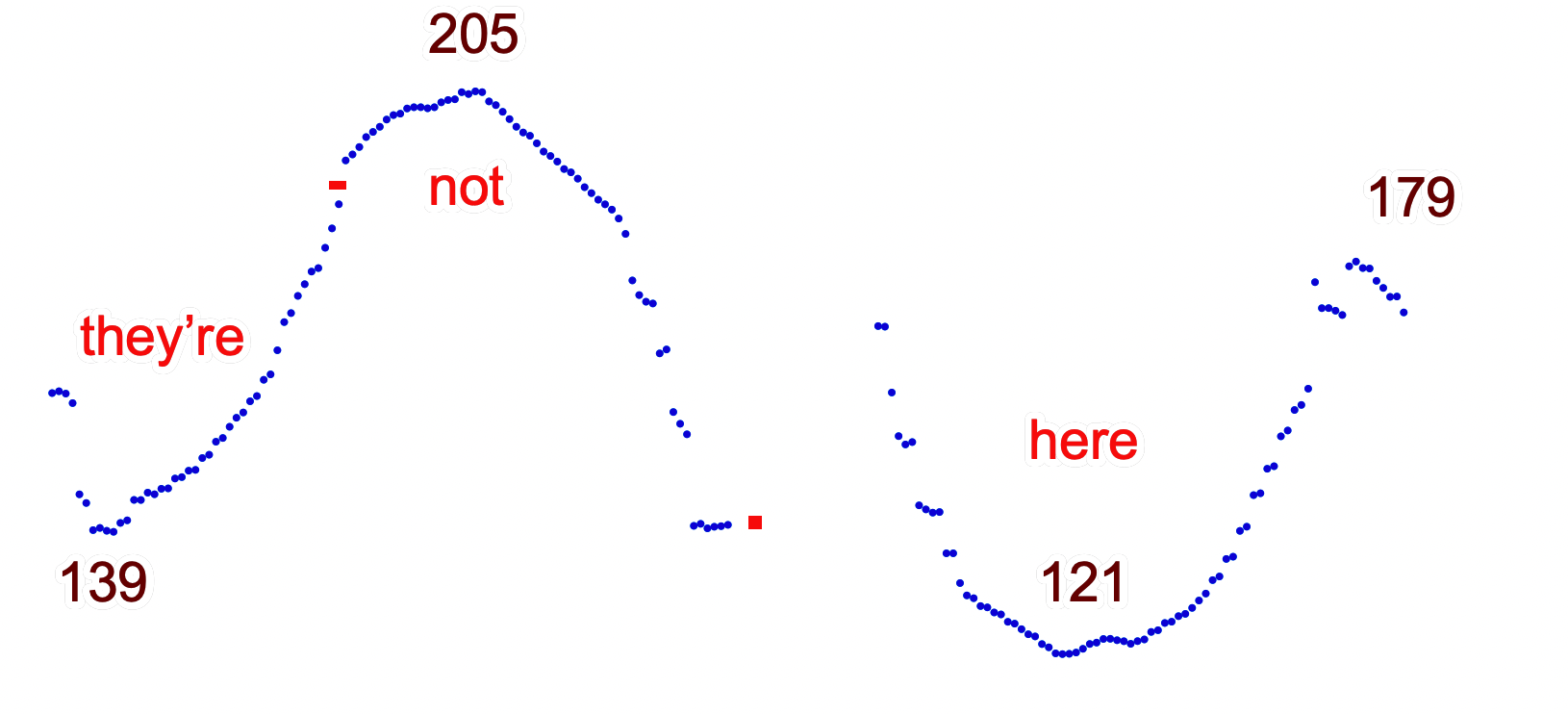

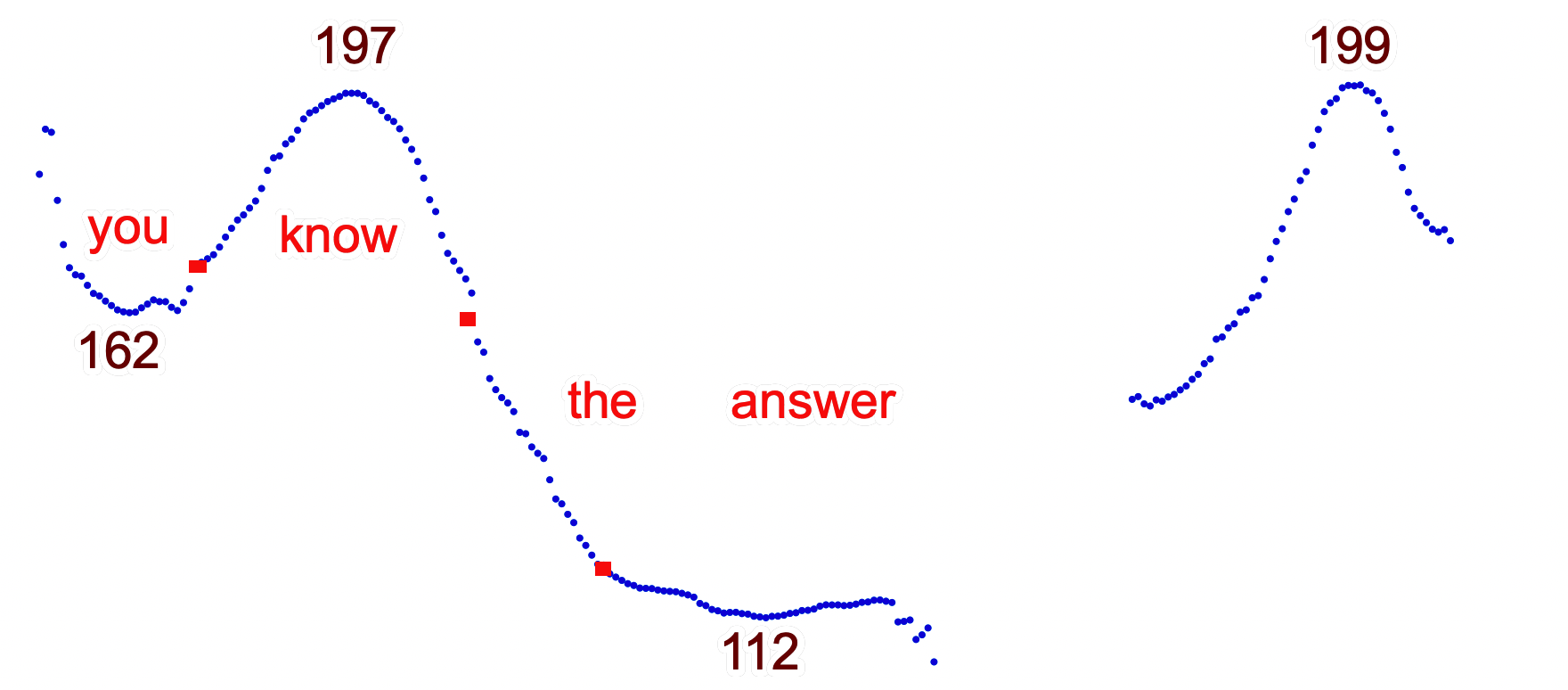

[The numbers in black are f0 estimates in Hertz (cycles per second)]

But today we're going to focus on the intonational choices, rather than the words-to-hum continuum. And the method will be socratic — we'll give examples, and ask questions. The answers will emerge in later installments, or perhaps in the comments.

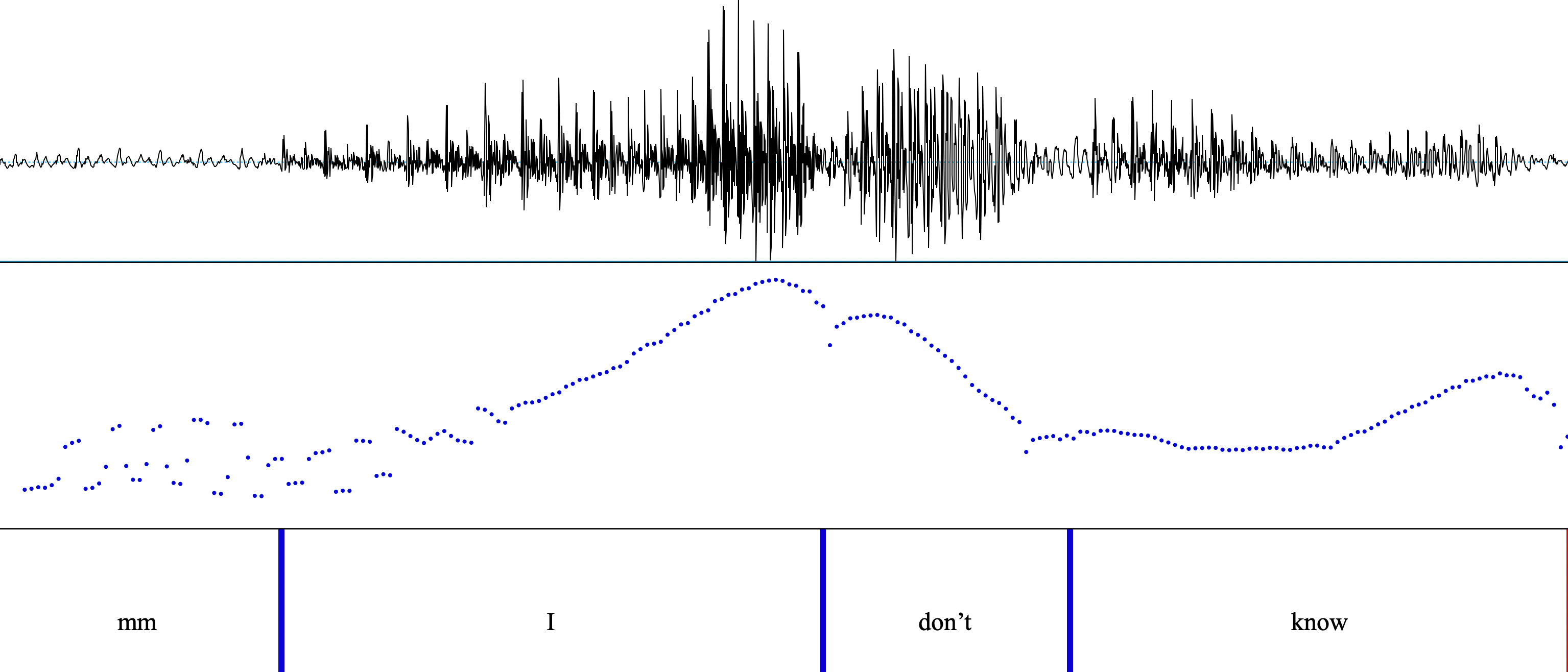

Here's a similar "I don't know" example, from "Bette Midler Takes On Girl Groups, From The Andrews Sisters To TLC", All Things Considered, 11/8/2014. The context is the talking part of Midler's cover of the Shangri-Las' Give Him A Great Big Kiss:

Here's the "I don't know" part by itself:

Is that the same contour as Ryan's hums and Homer's mumble?

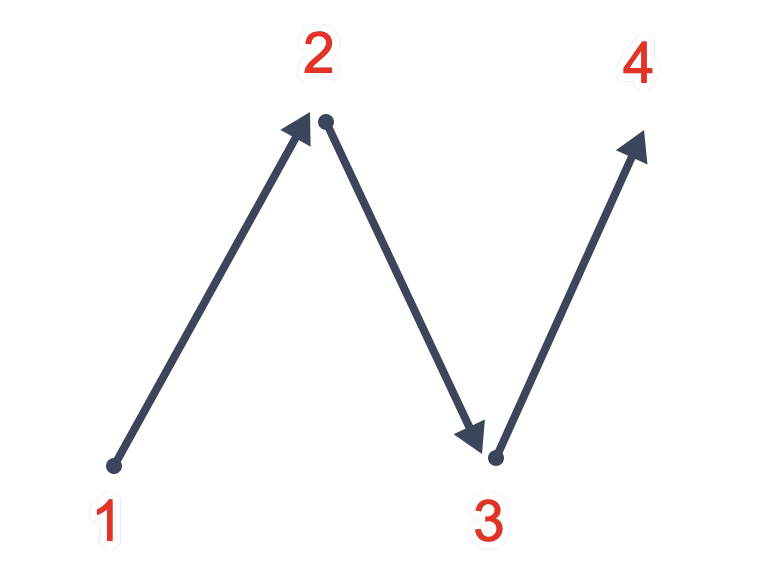

Well, they all have a rise, a fall, and a rise again — which we can schematize as a zigzag contour with four pitch targets:

But the various waggles are quantitatively different. For Ryan and Homer, target #3 is substantially higher than target #1, whereas for Bette, target #4 is the lower point in the sequence. Is that just like the gradient variation in Ryan's hums? Or is it a qualitative difference, like the distinction between "know" and "mow"?

Here's another example, from "Negroponte, Woolsey Advise Incoming DNI", Talk of the Nation, 6/15/2010, where James Woolsey tries to reconcile two apparently contradictory statements from James Clapper. The alignment of Woolsey's words with the tune is rather different from Midler's:

In Midler's performance, "I" is low, "don't" is rising", and "know" is falling-rising. In Clapper's version, "I" is rising, "don't" is falling, and "know" is level-to-rising. Again, is this part of a gradient pattern of alignment variation, or does it represent a categorical difference?

In any case, let's be clear — the intonational pattern under discussion has nothing special to do with knowing or not knowing. Rather (among other things) it's a way of signaling that your interlocutor is making a false assumption. That false assumption might be the idea that you know the answer to their question. But the assumption might be something else entirely, as in these examples (performed by me):

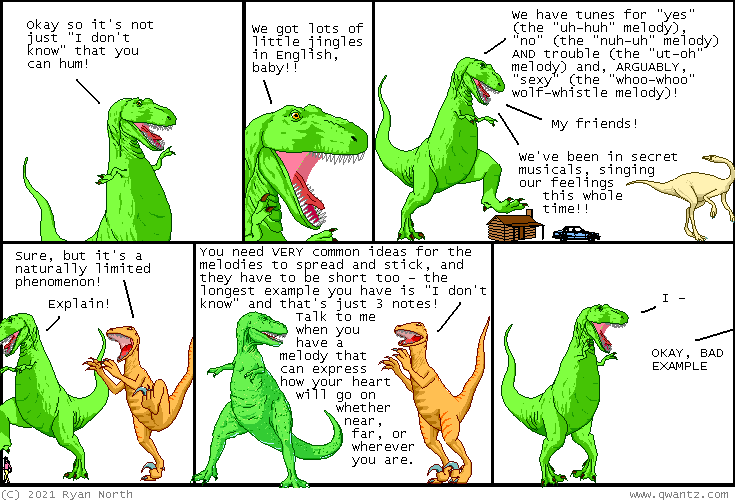

And the phrase "I don't know" can of course be performed with many other prosodic patterns. We'll give some examples, and survey the reader submissions, in the next installment. Meanwhile, the most recent Dinosaur Comics revisits the topic:

Mouseover title: "if you ever want to wordlessly express the idea of turtles that are both teenage, mutant, AND ninjas, then buddy, have i got an 8-note musical phrase for you"

Finally, let me note that in 1974, Ivan Sag and I presented "Prosodic Form and Discourse Function" at the 10th Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, with Ivan performing the intonation contours on the kazoo.

Michael Watts said,

August 31, 2021 @ 5:15 pm

The latest comic bothers me. The "I don't know" is defined by tune / tone / frequency pattern. And so is the wolf whistle.

But uh-huh / uh-uh / nuh-uh aren't. Tonal patterns associated with those are far more transparently about some other message being layered on top of the lexical item, and vary freely.

Michael Watts said,

August 31, 2021 @ 5:28 pm

I think https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n8mK-A_0viA&t=130s is an example of "I don't know" being given another prosodic pattern. That's how I process it, anyway, though it might be the same pattern compressed into a low range.

Stephen Hart said,

August 31, 2021 @ 5:46 pm

Two young neighbors, when my children were young, pronounced the phrase something like ahnuhno, all one word, similar to Bette Midler’s performance above.

(mid 1980s, pacific northwest )

JPL said,

September 1, 2021 @ 1:19 am

I'll send recordings of my imitations of the three year old and any other examples I hear in real life or on the telly as soon as I can figure out how to create and send an audio file on this computer. (I promise they'll be accurate.) Sorry about that.

WRT your first question ("Is that the same contour as Ryan's hums and Homer's mumble?"), I take it you mean something like, "Are these [contours in the examples under consideration] instances of one category, sort of like phonologically conditioned allomorphs?" I'm inclined to say, "Yes" (I'm not sure about the Woolsey example.), but that raises the question, "Is there an acoustic level principle that unifies these cases as differing manifestations of a single acoustically defined category?" I don't know the answer to that question, but that's why I'm looking out for examples of what I called in my comment to the first post the "emphatic version" of the milder hummable "I don't know" that the three year old used, because I think the two phenomena, with slightly differing acoustic properties, could be integrated to a single category. The "emphatic" version is not conventionally hummable, but I think the hummability is due to reasons that are irrelevant for the category. In addition, it is the stronger pattern that occurs more generally, as in your examples "they're not here" and "you know the answer", especially the latter, where the third tone (target) is lower than the first. I've always found these cases weird, because, unlike the milder hummable cases, these seem to involve stress, but here the focus of the stress gets the lowest pitch, as opposed to the usual case, where the focused element gets the highest pitch. Compared to the normal case, these contours seem to be "upside down" or inverted: maybe not perfectly, but you have the sequence "up-down-up", as opposed to the usual "down-up-down", with the lowest pitch getting the stress, rather than the usual case of stress with the highest pitch. (I don't know what a comparison of the acoustic patterns would show.) So this "inverted" contour does seem to function as a unit: one could probably, as a response in any relevant context, indicate that at least something is wrong by humming that contour alone. Finally, you touch on the possible general significance of this pattern ("a way of signaling that your interlocutor is making a false assumption"). I think this is right. One might go on to note that in the normal case of correction of an assertion, focus of both the negation and the substitution gets the highest tone, usually referred to as "contrastive stress" (e.g., "She didn't BOIL the beans, she SAUTEED them") (and BTW, this contrasting, and any verification process, involves reference; reference is not just about definite subject NPs); but in these cases with the "inverted" contour the correction is not of what is asserted, but of something the assertion depends on for its validity, a premise or an assumption, as you say. What is negated is the logically prior assumption, not the assertion. Anyway, this seems to be a possible working hypothesis; I haven't pursued it further than this. (And remember that any significance that this contour might have, if indeed it is a unified phenomenon, will itself have the structure of a category, with the usual internal differentiations, and that would be a semantic problem.)

jaap said,

September 1, 2021 @ 3:14 am

When this discussion started I immediately thought of Scooby Doo. A good example of his intonation can be found here:

https://youtu.be/NcfrD_mhXGI?t=193

Julian said,

September 1, 2021 @ 5:23 am

60yo Australian here. For what it's worth, this hummed no is not

part of my language. I was pretty much mystified by the whole thread before listening to the clips and I don't believe I've ever heard it in real life.

Maybe it's an American thing? What do the Brits who are reading think?

Julian said,

September 1, 2021 @ 5:36 am

In Greek 'no' is an upwards nod with raised eyebrows and half closed eyes and, if you wish, a click of the tongue against the palate. 'yes' is a downwards nod similar to ours but a bit more waggly than straight up and down. For example https://youtu.be/LAuegQ0i7e8

The lady in the middle is doing a Greek no, the one on the right a 'western' no.

Words for 'nod upwards' (no) and 'nod downwards' (yes) are in your ancient Greek dictionary (ananeuo and kataneuo), so presumably that means that these subtle and fleeting gestures have been passed down the generations for a looong time. Which is a pretty amazing thought.

Thomas Shaw said,

September 1, 2021 @ 7:30 am

I enjoyed this analysis a lot. I also enjoyed Ryan's (somewhat relevant) follow-up comic:

https://qwantz.com/index.php?comic=3791

Philip Taylor said,

September 1, 2021 @ 12:06 pm

Julian — "I was pretty much mystified by the whole thread[…] What do the Brits who are reading think?".

This Briton was as mystified as you.

Terry Hunt said,

September 1, 2021 @ 12:31 pm

Julian — This other (elderly) Briton, however, is perfectly familiar with the phenomenon and has pretty much comprehended the whole of the thread, absent some unfamiliarities with some of the foreign regionalisms. Don't mistake idiolectisms for dialectisms (if those are words — if not, I plead guilty to aggravated neologism).

JPL said,

September 2, 2021 @ 5:42 pm

The contour of the "milder hummable" version of the "I don't know" that we've been looking at also occurs more generally; it's not just the "stronger" version. How could I have missed that?! The two differ only in that the "distance" between the 2nd and 3rd pitch targets is shorter in the mild version; the difference in expressive effect is analogous to this acoustic difference, but both would be subsumable under one general principle. I don't know where "no" entered the conversation here, but in the past few days I also heard an instance of "no" uttered (as a one word answer) with what was clearly the "tail end" of the contour we've been talking about ("contour" here referring to the hypothesized category, not an individual), i.e., the one exemplified by Mark's "you know the answer": an acoustic description would show it as having a falling- rising pattern centred on the third pitch target (of the category's whole contour), that getting the lowest pitch in that person's normal intonation range, so I think clearly assimilable, and also with an expressive effect relatable to the other cases, in terms of negating prior assumptions. (BTW, the "interlocutor" element is probably a special case; the contour should apply to any case of logically prior assumptions from previous discourse (e.g., someone might say, "Wait a minute! It's not Sunday!" (I thought it was Sunday) with that contour.)

JPL said,

September 2, 2021 @ 6:40 pm

A minor clarification: when I said, "… the category's whole contour", I probably should have said something like, "the whole contour as determined by the category".

Viseguy said,

September 2, 2021 @ 7:17 pm

This topic takes me back 50 years to my beginning Linguistics class with Prof. Labov, who was fond of pointing out how some French speakers reduced je ne sais pas to something like shpo.

Andrew Usher said,

September 2, 2021 @ 10:54 pm

I think the most interesting question is whether the 'words-to-hum continuum' really is a continuum. Previously, it seemed we were assuming that this 'sung' I-don't-know was a separate phenomenon, but it seems clear it must have evolved from partly reduced versions. But isn't there a point that it becomes lexicalised, and if so have we passed it here? Can such a variant even arise in any other circumstance?

k_over_hbarc at yahoo.com

JPL said,

September 3, 2021 @ 10:11 pm

Another minor clarification, this time wrt the hypothesized meaning: I said above, "negating prior assumptions". A better way to state it is that it's not the negation that is expressed by the contour (the negation is expressed by the "not", etc.); rather the (available) contrast between the "inverted" contour and the one for "contrastive stress" expresses the difference between negation of a logically prior assumption and negation of what is asserted. (Sorry, this was bothering me.) But I (at least) am interested in what you've come up with on this problem, so I hope you post again on it.

milu said,

September 4, 2021 @ 11:41 am

so, the rise at the end that MYL had deduced a frequency analysis would evince is because of the diphthong in "know", right?

i wonder if dialects where the vowel in "know" is a monophthong /o:/ (e.g. Indian English i think? and Scottish maybe?) lack this final rise. assuming they hum their "i don't know"s.

tom davidson said,

September 4, 2021 @ 4:56 pm

Note that a popular Chinese social media rendition of I don't know is "idk."

Victor Mair said,

September 4, 2021 @ 9:23 pm

@tom davidson

I consider that "idk" to be quite significant, because it shows that, at least some of the time, Chinese netizens are thinking in English. There are many other examples, e.g., OMG ("Oh, my god!").

Mark F. said,

September 5, 2021 @ 10:39 pm

This Science Friday segment has a beautiful example of almost-hummed "I don't know" in the wild. Search the transcript for "[MUMBLED] I don't know". It was performative enough that another panelist referred back to it later in the show.

Mark F. said,

September 5, 2021 @ 10:47 pm

Correction: "[MUMBLING] I don't know".