To be anticipated

« previous post | next post »

Noam Chomsky in the Guardian uses 'anticipate' to mean 'expect'. I thought language was his thing.

— Daniel Hannan (@DanHannanMEP) May 1, 2012

Daniel Hannan is both a writer for The Telegraph and also Conservative MEP for South East England; and what he's complaining about is this passage (from "What next for Occupy?", The Guardian 4/30/2012):

But a lot of [the response], again, is just, "Why don't they go away and leave us alone?" That's to be anticipated.

Tom Chivers explains the matter further ("Expecting the misuse of the word 'anticipate': the real rules of the English language", The Telegraph 5/2/2012):

My colleague Daniel Hannan caught the great linguist and philosopher Noam Chomsky out in an error yesterday. Not an error of fact or judgment, although Chomsky is certainly capable of those (Steven Pinker, in The Blank Slate, points out several, largely related to Chomsky's innocence of evolutionary biology). No: Dan points out that Chomsky used "anticipate" when he meant "expect" in an article for The Guardian. "I thought language was his thing", Dan said on Twitter, pointedly.

It's pleasing to see that Dan has internalised the Telegraph Style Guide so well. The hallowed tome declares:

anticipate is not a synonym for expect; it conveys the meaning of acting in expectation of an event. A reporter who expects to be sent to Africa may anticipate the assignment by buying tropical clothes. A couple who anticipate marriage may, for instance, open a joint bank account.

The Telegraph is, of course, entitled to constrain its employees as it sees fit. But in the English language at large, anticipate has been used at least since the middle of the 18th century in a sense that the OED glosses as "To look forward to, look for (an uncertain event) as certain", which seems to fit Chomsky's usage exactly.

Some examples from notable writers of the 19th century:

Benjamin Disraeli, Vivian (1826):

Vivian made his escape; and Beckendorff, pitying his degeneracy, proposed to the Prince, in a tone which seemed to anticipate that the offer would meet with instantaneous acceptation —double dumbmy;—this, however, was too much.

("Double dumbmy" is an archaic spelling for "double dummy", which in turn is a form of whist "in which two ‘hands’ are exposed, so that each of the two players manages two ‘hands'".)

Thomas Carlyle, Sartor Resartus (1834):

For us, aware of his deep Sansculottism, there is more meant in this passage than meets the ear. At the same time, who can avoid smiling at the earnestness and Boeotian simplicity (if indeed there be not an underhand satire in it), with which that 'Incident' is here brought forward; and, in the Professor's ambiguous way, as clearly perhaps as he durst in Weissnichtwo, recommended to imitation! Does Teufelsdröckh anticipate that, in this age of refinement, any considerable class of the community, by way of testifying against the 'Mammon-god,' and escaping from what he calls 'Vanity's Workhouse and Ragfair,' where doubtless some of them are toiled and whipped and hoodwinked sufficiently,— will sheathe themselves in close-fitting cases of Leather? The idea is ridiculous in the extreme.

John Stuart Mill, "Tennyson's Poems" (1835):

Our first specimen, selected from the earlier of the two volumes, will illustrate chiefly this quality of Mr. Tennyson's productions. We do not anticipate that this little poem will be equally relished at first by all lovers of poetry: and indeed if it were, its merit could be but of the humblest kind; for sentiments and imagery which can be received at once, and with equal ease, into every mind, must necessarily be trite. Nevertheless, we do not hesitate to quote it at full length.

Charlotte Brontë, Shirley (1849)

Thirdly, he had found Robert himself a sharp man of business. He saw reason to anticipate that he would in the end, by one means or another, make money; and he respected both his resolution and acuteness; perhaps, also, his hardness.

Charles Dickens, The Personal History of David Copperfield (1850):

"Well! They must be paid," said my aunt.

"Yes, but I don't know when they may be proceeded on, or where they are," rejoined Traddles, opening his eyes; "and I anticipate, that, between this time and his departure, Mr. Micawber will be constantly arrested, or taken in execution."

Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species (1859):

From looking at species as only strongly-marked and well-defined varieties, I was led to anticipate that the species of the larger genera in each country would oftener present varieties, than the species of the smaller genera; for wherever many closely related species ( i. e . species of the same genus) have been formed, many varieties or incipient species ought, as a general rule, to be now forming. Where many large trees grow, we expect to find saplings.

H. Rider Haggard, She (1887):

We are for reasons that, after perusing this manuscript, you may be able to guess, going away again, this time to Central Asia where, if anywhere upon this earth, wisdom is to be found, and we anticipate that our sojourn there will be a long one. Possibly we shall not return.

And also John Henry Newman, John Ruskin, Sir Walter Scott, Anthony Trollope, and many others.

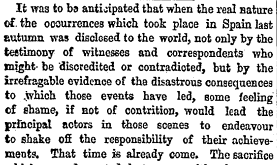

Chomsky's specific phrase "That's to be anticipated" has been anticipated many times in reputable publications. Thus the (London) Times for June 3, 1847:

So this feature of the Telegraph's Style Guide is pure prescriptivist poppycock, a typically ignorant and philistine rejection of more than a century of elite usage. Where did it come from? Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of English Usage explains the (all too typical) history:

The original objection seems to have been made by Ayres 1881. Ayres decided that certain examples he had collected meant "expect" and were wrong. To prove his contention, he points to the etymology of the word and a number of different definitions presumably taken from an unnamed dictionary, none of which is "expect." This is merely a game being played with the words that have been used to define anticipate; nothing whatsoever has been proved. But no matter.

The cited source is Alfred Ayres, The Verbalist: A Manual Devoted To Brief Discussions Of The Right And The Wrong Use of Words; And To Some Other Matters Of Interest To Those Who Would Speak And Write With Propriety. This little book is full of wonderful nuggets of nonsense, such as the recommendation to use "anybody's else" in place of "anybody else's":

It is better grammar and more euphonious to consider else as being an adjective, and to form the possessive by adding the apostrophe and s to the word that else qualifies; thus, anybody's else, nobody's else, somebody's else.

Considering his evident impact on journalistic style guides and Conservative Members of Parliament, it's a sad fact that Alfred Ayres apparently has no Wikipedia page. (Update — "Alford Ayres" was the pen name of Thomas Embly Osmun, who also lacks a Wikipedia entry.)

[I should note that Tom Chivers' article, once you get past its tongue-in-cheek beginning, is generally sensible, if perhaps a bit cautious about his publication's style guide; the poppycock in question belongs to Mr. Hannan's tweet.]

Wells Hansen said,

May 3, 2012 @ 12:24 am

I have heard this claim about "anticipate". Similarly, I've heard educated folks proclaim (loudly) that "transpire" should have only the meaning "come to to be known." But good writers use "transpire" to mean "happen". Perhaps such restrictive, often etymological, claims are made by persons who have simply glanced at a dictionary entry? It's easy for me to get the wrong idea about a word, especially a foreign word, if I don't slow down and read carefully.

Ray Girvan said,

May 3, 2012 @ 1:03 am

Here's an Internet Archive copy of The Verbalist: Mark's link presumably only works for US readers.

Rubrick said,

May 3, 2012 @ 2:28 am

Sure, Dickens, Carlyle, et. al used it that way, but I don't think language was really their thing.

LDavidH said,

May 3, 2012 @ 3:04 am

It's funny; I agree with the general idea that "anticipate" and "expect" are synonyms, but in this particular case ("It's to be expected"), "anticipated" still sounds wrong.

Ben said,

May 3, 2012 @ 3:29 am

And anyway, as far as I can tell, the etymology of anticipate would be ante-incipere – "to begin beforehand" – which COULD mean to act in advance of something happening, but certainly doesn't preclude the idea of simply considering the event before it "begins" in earnest.

So you know.

Language.

D said,

May 3, 2012 @ 3:32 am

Since this Language Log post is the top Google result for "to be anticipated", it's probably not a very common usage. But you do get 11 000 000 results (allegedly, since google's estimates aren't very accurate). And there are 36 900 results for "it's to be anticipated".

Andrew said,

May 3, 2012 @ 3:35 am

I agree with LDavidH – "expected" is the natural word to use here, and using "anticipated" makes it looks as if you're trying to sound clever (cf Fowler's "love of the long word").

D said,

May 3, 2012 @ 3:38 am

Or… since I just noted "to be anticipated" is the exact title of this post, disregard the first sentence of my comment :)

Murray Smith said,

May 3, 2012 @ 5:04 am

Mark, Ayre's "anybody's else" is to be contrasted with "anybody else's" (not with "anybody else"). Probably just a typo, but it obscures the sense of the idea. Like everyone else, I have chuncked "anybody else" into a unit, so that the possessive fits nicely on the end, but I think "anybody's else" has a nice faux-elegant ring to it. I sometimes even say it, to make an effect.

[(myl) Sorry for the omitted apostrohe s — it's fixed now. But really, "He refused to consider anybody's else idea"? Or even "… anybody's idea else"? This certainly makes an effect, but is it the effect that you want?]

Steve F said,

May 3, 2012 @ 6:21 am

The Telegraph's style guide's intolerance for what is surely – contrary to what D says above – the most common meaning of the word 'anticipate' in current usage, is typical of a conviction that seems to be held by many prescriptivists that a word can only have one meaning, and that meaning must be its original one. I – like any native speaker – am quite capable of keeping the meaning 'expect' distinct in my mind from the meaning 'act in preparation for an expected event' that the Telegraph prefers. What's more I can simultaneously manage to remember that it also means 'to forestall', 'to look forward to with pleasure', 'to give advance thought or preparation to','to pay a debt before it is due', and probably a few more meanings I can't bring to mind just now, without consulting a dictionary anyway.

Similarly, I have no problem holding more than one meaning of, say, 'aggravate' or 'disinterested' in my mind, and find that it is always clear which meaning is intended from the context.

Are people like Daniel Hannan just very stupid, and really can't cope with one word having multiple meanings, or do they just think the rest of us are? And why do they assume that, because they have read some single 'authority' such as the Telegraph style guide, they know more about language than Noam Chomsky? I know that a lot of Chomsky's ideas are by no means universally accepted, but that's not because he hasn't studied the Telegraph style guide closely enough. I suspect that Daniel Hannan's evident delight in 'catching out' an eminent linguist has more to do with his opinions about Chomsky's political and social views, and, like so many people, he thinks that a cheap (and inaccurate) gibe about somebody's linguistic competence in some way invalidates all the other opinions they hold.

Mov said,

May 3, 2012 @ 9:05 am

Now that we know the Telegraph is prescriptivist in a way which does not represent natural human language performance (nor competence): does it still qualify for contributing to corpora?

BZ said,

May 3, 2012 @ 9:52 am

"A reporter who expects to be sent to Africa may anticipate the assignment by buying tropical clothes. A couple who anticipate marriage may, for instance, open a joint bank account." This maybe a UK versus US thing, but I wouldn't use anticipate in that way at all. To me, this sense of anticipate implies something unexpected, so anticipating marriage would imply that marriage does not seem to be likely, but they took some action just in case.

I would use anticipate in something like "I anticipated your move" in chess, meaning I was protected myself because I thought of this possibility. Or "he anticipated every eventuality", again, not because he expected every eventuality and acted to prepare, but because he thought of every eventuality. How can you even expect every eventuality? They all contradict each other.

Just to be clear, I find "that's to be anticipated" to mean expected unremarkable.

Ellen K. said,

May 3, 2012 @ 9:57 am

I like "That's to be anticipated" in the original example. It comes across to me as conveying a slightly different meaning than "That's to be expected" would, and I find it fitting that someone for whom "language [is] his thing" would use it.

Bob Moore said,

May 3, 2012 @ 10:24 am

I agree "That's to be anticipated" is not an error, but it is also not very idiomatic English. If you look at the Google ngram viewer, you will see that "to be expected" has always been at least two orders of magnitude more frequent than "to be anticipated", despite the fact that "expected" is less than one order of magnitude more frequent than "anticipated". To me, "anticipate" usually carries an implication that the event in question is viewed positively by the anticipator, which seems to be supported by the fact that, again according to the Google ngram viewer, "eagerly anticipated" is about an order of magnitude more frequent than "eagerly expected".

The Google ngram viewer also reveals some interesting recent trends in the use of some of these phrases. Usage of "to be expected" seems to have fallen by about a factor of three since the early 1950s, while usage of "eagerly anticipated" has roughly doubled over the same period.

dw said,

May 3, 2012 @ 10:26 am

From Chivers's pontification:

The reason it is "disp" is that people, including our style guides, tell us not to use it like that.

So style guides are people?

What Chomsky, and Pinker, have worked on for much of their careers is how much of the construction of the rules of grammar are innate in humans.

Shouldn't that be "is innate in humans"?

Two can play at the pedantry game.

Tom Chivers said,

May 3, 2012 @ 11:02 am

DW: it should indeed be "is" – some commenters have pointed it out. I felt it was only fair to leave it in, as a testament to Muphry's Law.

(Besides: I rather thought I was being antipedantic, if that's a word.)

Coby Lubliner said,

May 3, 2012 @ 11:49 am

I wish that the category "Prescriptivist poppycock" could also be applied to linguists (including those of LL) who pontificate against nontechnical use of such terms as "grammar," "passive voice" and "linguist." Where is Norma Loquendi when you need her?

[(myl) But wait a minute — "passive voice" really is a technical term. The complaint is not about uses of "passive voice" that are nontechnical, it's about uses that pretend to be technical but are wrong, in an incoherent and vague sort of way. It's like calling a compact fluorescent bulb a "light-emitting diode". ]

Jerry Friedman said,

May 3, 2012 @ 12:44 pm

The MWDEU also "credits" Ayres with inventing the healthy-healthful distinction (page 500).

Jerry Friedman said,

May 3, 2012 @ 2:44 pm

By the way, if anyone wants to write his biography, his real name was apparently Thomas Embley Osmund or Osmun. (Yes, it's the same Alfred Ayres.)

Neil Dolinger said,

May 3, 2012 @ 2:52 pm

"I've heard educated folks proclaim (loudly) that 'transpire' should have only the meaning 'come to to be known.'"

They are WRONG! It should only mean to "blow across".

jk

Nathan Myers said,

May 3, 2012 @ 2:58 pm

Where I come from, "anticipate" differs from "expect" and "fear" in the attitude toward the upcoming event. We anticipate marriage, expect rain, fear an assault. That's local usage, but I wonder how common it is.

Morten Jonsson said,

May 3, 2012 @ 4:28 pm

As I see it, "anticipate" in the sense of "expect" can also suggest the other sense of the word—it implies not only that one expects some event to happen, but that one is preparing to deal with it. And note that that's exactly how Chomsky uses it—he says that a particular action is to be anticipated, and in the very next sentence discusses how to respond. "Expected" would have done perfectly well too, but that prophylactic sense isn't quite as strong. To my mind, anyway, and I think to Chomsky's.

diogenes said,

May 3, 2012 @ 4:44 pm

at moments like this I just try to remember what exspecto meant in latin – to wait for. Not very many cases of the waiting for something special that "expect" tends to connote.

austin pratt said,

May 3, 2012 @ 5:18 pm

Expect is in the Oxford dictionary definition of anticipate.

Coby Lubliner said,

May 3, 2012 @ 5:46 pm

myl: Of course "passive voice" is a technical term. So are "gridlock," "quantum leap," "begging the question" and many others. They are used by people outside the relevant disciplines (traffic engineering, physics and logic, respectively) with meanings quite different from the technical ones, even when they are talking about a phenomenon treated by the discipline in question (traffic reporters sometimes refer to "gridlock on the bridge"). But then again, specialists have appropriated terms from the general lexicon and given them narrow technical meanings ("grammar," "linguist" and "creole" fall into this category). Isn't that just how language works?

Eric P Smith said,

May 3, 2012 @ 5:51 pm

I think there are two sorts of people: those who are purist and traditionalist, and those who swim with the tide. I have no difficulty with the purists, who consider that the strict meaning of "anticipate" is "act in advance of" and who consider other usages to be loose. Nor have I any difficulty with those who swim with the tide, and use "anticipate" to mean "expect". It is a pity when the two sorts are at each others' throats.

I tend to be purist in my own usage, but not to complain at other usages.

Coby Lubliner said,

May 3, 2012 @ 5:52 pm

Addendum: What I mean is that "passive voice" has — like it or not — acquired, outside of grammar (in the narrow sense), a meaning something like "impersonal style."

[(myl) Indeed:

]

I don't see how calling it "wrong" is different from any other sort of prescriptivism.

[(myl) Well, there's a difference between simple extended meanings and misunderstood technical terms, like talking about 110 watts when you mean 110 volts, or using "marsupial" to mean "rodent".

And the difference is magnified if we compare that sort of prescribing with wholly invented "rules" elevating personal quirks to the status of usage norms.]

Murray Smith said,

May 3, 2012 @ 9:32 pm

Mark, re "anybody's else". It certainly doesn't work before a noun, as you point out. I accept that idea of yours, but I don't accept anybody's else. If one were to analyze "anybody else" (which we don't, now, but presumably we once did), the possessor (if there is one) is "anybody", and the "else" modifies it. Google ngram viewer shows that around 1900 "anybody's else" was about one-fourth as frequent as "anybody else's", but it has faded since then. Plus which (as George V. Higgins used to write, God rest his soul) your own spellchecker is underlining else's for me, but not anybody's.

Chaon said,

May 3, 2012 @ 10:07 pm

Mark Lieberman in the Language Log uses 'poppycock' to mean 'balderdash'. I thought language was his thing.

(Because what 'poppycock' really means is 'soft stool')

Michael Briggs said,

May 3, 2012 @ 10:41 pm

Where I come from, if you anticipate marriage you sleep together while you're engaged.

Michael Briggs said,

May 3, 2012 @ 10:45 pm

And wooden buildings, I guess, are never dilapidated.

J. Goard said,

May 4, 2012 @ 1:16 am

Expect is one of the words that frustrates me the most in the English used by the Korean speakers around me, because of the sense of entitlement it attributes to its subject whenever its complement involves some kind of voluntary action on the part of another person. So, whether the complement is an infinitive clause with unexpressed subject coreferential with the matrix subject (1) or is a distinct subject (2), or is a nominal (3), I'm challenged to distinguish the perfectly fine (a) sentences with the (b) sentences where using expect will make you come across as a jerk:

(1) a. I expect to have a lot of fun this summer.

b. # I expect to have a lot of fun at your party.

(2) a. I expect the economy to recover quickly.

b. # I expect you to recover from your cancer.

(3) a. I expect a lot more rain in Ohio this year.

b. # I expect a lot more sexual assaults in Ohio this year.

Anticipate (though it doesn't take an infinitival complement) at least avoids this subtle but potentially critical pragmatic problem. These days, I reflexively prefer it (or a whole host of other constructions) to expect.

Dan H said,

May 4, 2012 @ 3:57 am

I agree with those who, formal definitions aside, find "that's to be anticipated" to sound odd. I'm struggling to put my finger on *why*, however.

Tom Saylor said,

May 4, 2012 @ 4:57 am

TSG:

I wonder what the Telegraph Style Guide has to say about 'unanticipated', which apparently has been in use since the 18th century. Does it insist that the word is properly applied only to an expected event that has not been acted upon in advance, e.g., a trip to Africa or a marriage for which no preparations have been made? I don't think I've ever seen the adjective used in that sense.

The TSG's implicit prescription (it doesn't explicitly prescribe or proscribe any verbal behavior here–doesn't explicitly say one should not use 'anticipate' in this way) is not worth following, but I don't think it's prescriptivist poppycock–if by 'poppycock' we mean a claim that is wildly false. Prescriptions (deontic statements) are neither true nor false. No, the TSG's observation about 'anticipate' is descriptivist poppycock, pure and simple.

Joanne Salton said,

May 4, 2012 @ 5:29 am

I sometimes wonder why people are so keen to play strong prescriptivists at their own game by citing Dickens etc.

Surely it matters little what was said/written in previous centuries, if we adopt a descriptive viewpoint.

[(myl) Surely the reason is obvious. It's trivial to find current examples of anticipate used in the sense forbidden by the Telegraph's style guide — just search Google Books or any newspaper index for e.g. "anticipate that", and you'll find as many as you like. The expected rebuttal, especially from self-described "conservative" sources, is that this is just a symptom of modern linguistic and cultural degeneracy, we need to keep up standards, etc. So it's useful to point out that the usage in question is not some modern error, but has been common in elite writing for a couple of centuries.]

This Week’s Language Blog Roundup | Wordnik said,

May 4, 2012 @ 9:15 am

[…] Victor Mair examined a new non-stigmatizing Chinese word for epilepsy; and Mark Liberman considered Noam Chomsky and anticipation. Geoff Pullum discussed ongoing lexical fascism, a couple of rare words, and at Lingua Franca, the […]

Andrew (not the same one) said,

May 4, 2012 @ 10:27 am

Coby Lubliner: I totally agree with you about 'grammar' and 'linguist', but I would say that 'passive voice' is a different matter. Most people who use that expression, so far as I can see, think they are referring to a grammatical form, while being quite unclear as to what that form is. Some, for instance, think that any sentence including the word 'is' is in the passive voice. If the term really has simply acquired a new, non-technical sense, then I agree no one has a right to complain. But it seems to me this hasn't happened yet. There is, I guess, sometimes a fuzzy line between the misuse of a technical term and development of a new sense, but I don't think it has been crossed yet.

Coby Lubliner said,

May 4, 2012 @ 11:48 am

Andrew (not the same one) [not the same one as who?]: I hope you're right — I personally don't like to see technical terms misused — but if the examples cited by the LL folk are any indication, the line seems to have been crossed. The case is similar to "gridlock": from a technical meaning (traffic blocking intersections in a street grid) to a metaphorical one ("legislative gridlock") back to an inaccurate literal one. So it seems to have happened with "passive": the metaphorical meaning ("weak") reverted to a literal one misapplied by ignorant teachers and editors.

I might have suggested that grammarians abandon the term "passive" to the laity and replace it with, say, the Greek equivalent, but that would be… pathetic (παθητική)!

Andrew (not the same one) said,

May 4, 2012 @ 2:09 pm

I honestly don't know who I'm not the same one as. I adopted the name in one thread where another Andrew had posted before me, and then kept it so as to have a consistent identity, since there are lots of Andrews about.

joanne salton said,

May 5, 2012 @ 3:49 pm

My point is though that it rather seems to give the impression when you cite Dickens that if Dickens wrote something then it must necessarily be good current English. Indeed, one previous poster with a descriptive viewpoint took exactly that view and laughed at the prescriptivists for suggesting that something found in the great Dickens might possibly not be acceptable. Thus while it is a reasonable way to convince people that they are wrong about such-and-such a usage being a new and ignorant mistake, this (rather common) response always reinforces the mistaken view that authority is key, not usage.

[(myl) In this kind of discussion, there's a big difference between an appeal to authority of the form "Strunk (or Fowler or Ayres or …) said you must always (or never) do X", and an appeal to authority of the form "Dickens (or Carlyle or Austen or Eliot or Yeats…) routinely employed construction or usage X". The first is the prescription of a self-appointed authority; the second is a description of the practice of well-regarded writers.

In relation to such descriptions of practice, it's certainly in order to consider the time period. But when we have a usage that's been common among well-regarded writers for several hundred years, prescriptive advice against it is especially unlikely to be valid.

I could have cited Alice Munro's 1977 The Moons of Jupiter:

Iris's lipstick, her bright teased hair, her iridescent dress and oversized brooch, her voice and conversation, were all part of a policy which was not a bad one: she was in favor of movement, noise, change, flashiness, hilarity, and courage.

…or countless other recent works by living authors. But a common response is to take such citations as evidence of failure to maintain standards.]

Dan Hemmens said,

May 5, 2012 @ 6:26 pm

I think the problem is somewhat muddied here by the fact the non-technical (or perhaps we should call it quasi-technical) use of "passive" is very, very inconsistent. As Andrew (not the same one) points out, some people think that a passive clause is any clause with a form of the verb "to be" in it. Others think that "the passive voice" is any form of expression that is vague about agency (or indeed that fails to place blame where the complainant feels it should be placed). Still others think that "the passive voice" means anything that is in any way weak.

To put it another way, the problem with the "non-technical" definition of "passive voice" is that it only makes any sense at *all* if you mistakenly believe it to be the real, technical definition. The popular uses all claim to identify a particular way of using English, when they don't. When people say that a particular passage "avoids agency by using the passive voice" they clearly think that there is some particular type of language being used and that they are able to identify it.

Context is also important here. "Passive voice" is very different to "gridlock" in the sense that it isn't a word people use casually, rather it's a technical term that people attempt to use in technical analysis.

Perhaps a better analogy than "gridlock" would be "quantum" or possibly "genetic". "Genetic" has a very specific meaning in biology (it means, well, literally encoded in DNA) but tends to get used in everyday speech as a synonym for "hereditary" or "predetermined". This is all well and good, but once people start trying to make actual testable claims about the physical world that rely on pretending that the pop-culture definition is the same as the scientific definition (like, say, in pretty much every newspaper article about genetics you'll ever read), you really do have to sit down and say "no, you are using that word wrong". Which is really a shorthand for saying "you appear to be assuming that your understanding of a metaphorical idea which, confusingly, has the same name as a real scientific concept, is the same as understanding the scientific concept itself and you are now making false claims about an area of science you do not understand."

It is perfectly fine for people to use "passive" to mean "vague about agency" or "weak" or "contains a form of the word to be" but if those are the definitions you're using, you can't pass your comments of as an actual analysis of the language, any more than you can pass off your observation that you and your dad both like the same kinds of books as an actual analysis of the biochemistry.

W. Kiernan said,

May 5, 2012 @ 8:41 pm

Maybe Chomsky actually meant "anticipated" rather than "expected"; that is, not only expected, but prepared-for with counterarguments ("I'll tell you why they shouldn't go away and leave us alone!").

Chris said,

May 6, 2012 @ 7:40 am

With respect to the use of "passive", the problem is that would‐be dispensers of writing proscriptions use it the way that people like Deepak Chopra use the word "quantum". They rely on its status as a technical term to convey a sense of authority and expertise that they do not in fact possess. Peddlers of woo writing advice rely on the prestige of real linguistic description and its associated terminology, just as peddlers of woo medicine rely on the prestige of physics or biology. That, to me, is the major reason that the widespread misuse of "passive" as a technical term is a problem.

Jo said,

May 8, 2012 @ 1:06 pm

It strikes me that quoting Darwin in support of anything isn't going to have much weight with Neanderthals.

Jonathan Gress-Wright said,

May 8, 2012 @ 1:32 pm

The conversation about "passive voice" and prescriptivism on the part of professional linguists reminds me of Conquest's Law (named after the reactionary historian Robert Conquest): Everyone is a reactionary in the subject he knows about.