What an English major knows about "adverbs"

« previous post | next post »

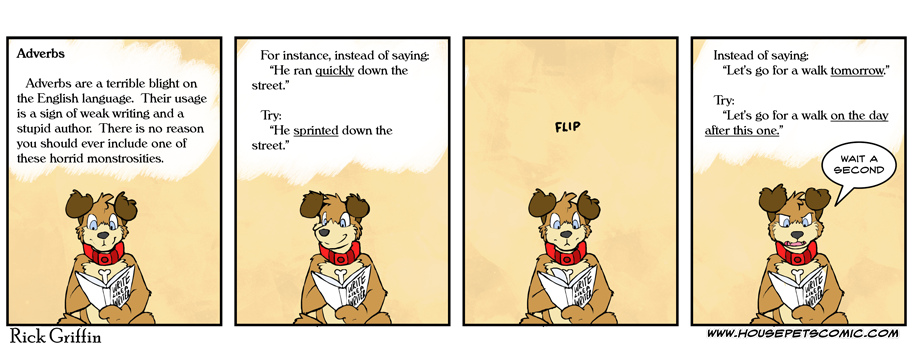

Housepets for 9/23/2011:

(Click on the image for a larger version.)

The author's chosen title for this strip is "An English major wrote this", and the mouseover title is a joke about a modern English major's stereotypical level of grammatical knowledge: "But what is an adverb? An adverb is any verb that describes an advertisement".

Many English majors know better — including, no doubt, Rick Griffin — but this is generally not because they've learned anything about the topic in their courses. The rest of them, along with those who majored in other subjects or avoided college altogether, are left mired in a state of "nervous cluelessness" about grammar and style. One source of this anxiety is acceptance of the dimly-remembered doctrine that adjectives and adverbs are Wrong and Bad, coupled with a disquieting uncertainty about what adjectives and adverbs really are.

A few discussions of modifier-phobia from our archives:

"Those who take the adjectives from the table", 2/18/2004.

"Modification as social anxiety", 5/16/2004

"The evolution of disornamentation", 2/21/2005

"Automated adverb hunting and why you don't need it", 3/5/2007

"Worthless grammar edicts from Harvard", 4/29/2010

[Tip of the hat to David Starner]

Oskar said,

September 26, 2011 @ 6:59 am

I might be opening up myself to ridicule here, but isn't "tomorrow" an adverb in that sentence? I suppose "on the day after this one" is an adverbial clause, but if the rule was "never ever use an adverb", the writer did accomplish that, didn't he? I know the rule is completely idiotic, but if the intent was to blindly follow it, it seems that he did in this case.

[(myl) You're entirely correct — the fictional silly-usage-advice book that the dog is reading correctly identifies quickly and tomorrow as (what dictionaries would identify as) adverbs. The point of the joke in the strip is that eliminating an adverb by substituting a more specifically flavored verb sometimes counts as "omitting needless words", but eliminating an adverb by substituting an unidiomatic and long-winded prepositional phrase functioning as an adverbial adjunct doesn't. Needless to say, a real-life silly-usage-advice book wouldn't give the second example.

So the joke depends less on the advice-book writer's failure to understand what adverbs are, at least as the lexical category of individual words, than on their failure to understand (or at least to think about) what adverbs do.]

jfruh said,

September 26, 2011 @ 8:47 am

What do you suppose the most effective way is to break the long-standing and pervasive myth that English majors study the grammar and linguistics of the English language? Should university English departments universally change their names to "literature departments," since that's what they study, as a rule?

Geoff Nathan said,

September 26, 2011 @ 9:08 am

Should university English departments universally change their names to "literature departments," since that's what they study, as a rule?

Speaking as a linguist in an English Department, married to the Chair of the 'Other Languages' Department, I'd advise against this, because university-level foreign language departments also study literature, and they'll be glad to point this out to you, loudly.

But your point about public perception is indeed well-taken.

B.T.Carolus said,

September 26, 2011 @ 9:24 am

@jfruh: my English dept. required at least two courses on grammar and linguistics, and it was possible for students to take even more (which I did). I think it would be better for more English departments to start requiring that instead of reducing themselves to purely literature based departments.

Dick Margulis said,

September 26, 2011 @ 9:35 am

What B.T. said. We have a pervasive myth that a degree is subject X from university A is pretty much the same as a degree in subject X from university B. But requirements vary widely.

Engineers, for example, who are graduates of university A have to demonstrate the ability to write coherently in English. They don't have to produce literature; they have to produce competent technical writing. But at universities B through Z, there is no such requirement. People who hire engineers are not amused by the discrepancy.

John Lawler said,

September 26, 2011 @ 10:13 am

Alas, I fear it would be pointless to have a grammar requirement in an (American) English Department unless all of the English Department faculty actually knew something about English grammar.

I've taught in English Departments here and there, and it has never been the case, in my experience, that all, or even most of, the faculty are lucid, or even sane, on the subject of actual English grammar.

They all know the catechism of shibboleths, though. And why not? Their teachers felt the same way; it's Traditional.

Rodger C said,

September 26, 2011 @ 10:20 am

Linguistics isn't the only thing English majors would benefit from studying. Deconstructionism is the result of English majors' assuming they can learn philosophy adequately by osmosis in their English courses. I'm not just being an old grump–this is a long-standing problem. Unthinking relativism as a herd attitude in humanities departments was preceded by unthinking rationalism (in my undergrad days) and (well before my time) by unthinking Hegelianism.

Re "acceptance of the dimly-remembered doctrine that adjectives and adverbs are Wrong and Bad, coupled with a disquieting uncertainty about what adjectives and adverbs really are": I take it that the cause of this is the abolition of formal grammar training in K-12 over the past 40 years or so in obedience to ed-school dogma. College English teachers have spent a great deal of time talking to their students under the assumption that the latter knew what these words mean, when many of those students have in fact never met the words before. A still more egregious result of this is the "passive voice" business.

Spell Me Jeff said,

September 26, 2011 @ 12:14 pm

I can really only speak for my own generation (I'm 48) and earlier generations of English faculty.

The overwhelming majority know English grammar in a Strunkenwhite sort of way, which means that much of what they "know" is incorrect or ill-advised.

They believe that bleeding red ink all over essays of students who have little grasp of the written dialect should lead to improvements, and that when improvements do not materialize, it is the fault of the student rather then the pedagogical method. (I have actually observed a faculty member write a sentence fragment on the board, label it as such, and admonish her students not to write like that. End of lesson.)

Virtually none can do such a seemingly simple thing as offer a perplexed student useful advice for identifying the verb of an independent clause.

In short, they believe that their ability to compose coherent, even elegant prose, and a passing familiarity with formal terminology makes them experts in grammar and in the instruction thereof. It does not.

Simon Spero said,

September 26, 2011 @ 12:23 pm

Assume a walking, walking1, and that the date of walking1 is tomorrow, and that an actor in walking1 is you and that an actor in walking1 is me . I desire that walking1 exists.

Andy said,

September 26, 2011 @ 12:24 pm

I don't think "English departments" teach English grammar the way "Computer Science" departments teach Java/C++/Pascal/[any computer programming language] grammar. I learned more English grammar structure in my Spanish classes than I did from my English classes in High School. I've gotten some odd looks from my wife when I use the phrases "parse" or "syntax error" in reference to processing an English sentence and she's the English grad.

Thanks,

Andy

Spell Me Jeff said,

September 26, 2011 @ 12:29 pm

You would be mistaken. There exists a pervasive myth among those who write "grammatically correct" sentences (especially if they are above a certain age) that they learned the skill in school. Formal grammar instruction certainly was not wasted on such folk. It gave them a vocabulary for describing what they know, and enough new knowledge that they were able to put finishing touches on what they already did well.

But the majority of good writers came to grammar instruction already prepped to write well. The two major factors are these: the extent to which the English they spoke at home was consistent with the written dialect; and the extent to which they read on their own.

As I explained to my 9th-grade English teacher, I was bored by grammar instruction because all I had to do was go with "what sounds right" and it would be right.

Kids who do not read absorb next to nothing from formal grammar instruction in school, the major exception being a negative attitude toward language arts generally.

You want kids to write better? Get 'em reading, in school and in the home, as early as possible. Supplement that with sentence combining exercises, and you'll get better writers.

Dan M. said,

September 26, 2011 @ 12:34 pm

I wonder if it was intentional, but I like how the first example substituting "sprinted" for "ran quickly" demonstrates the other endemic problem with usage advice.

Only small fraction of the situations involving running quickly actually involve sprinting. If the context of this sentence is to introduce a character who's out of their morning exercise, and to indicate that they are fleet, then this is an incorrection. If the context is to show that the character is fast-thinking and is solving a problem by running up the street, this is an incorrection.

I do wonder if this is a particularly common error because most usage advice is given in the context of free composition, where there isn't much constraint to keep accurately to some underlying reality that's being described. But if that's the problem, does this mean that this advice also distorts fiction writing away from the meaning intended by victims of this advice?

Philip said,

September 26, 2011 @ 12:40 pm

When I started teaching at the community college level 'way back in 1973, I was just finishing up an MA in English, so I'd learned quite a bit about the history of British and American literature. The courses I taught weren't lit courses though. They were composition courses, most of them remedial.

I'm sure this experience is not unique. What I did, repeat the "chatechism of shibboleths," is probably what most newly-minted English teachers do, too. I got lucky (timewise, anyway), went back to grad school, and studied linguistics. It's what kept me sane over all these years.

With that said, I think a focus on grammar, whether it's a traditional, Latin-based English grammar lacking both descriptive and explanatory adequacy or a modern generative-transformational grammar is an utter waste of time. We know that students who are native speakers of English have internalized English grammar. That's what "native speaker" means. The trick is to get them to use this internalized grammar when they write–and to understand that academic writing (what I learned to call Standard Written Academic English in grad school) is simply a different register, no "better," no "worse," than theirs.

There's a whole raft of literature out there, dating from at at least the late 60s, demonstrating that there is little correlation between one's formal knowledge of grammar and one's ability to write well. Passing a grammar test is different from writing a paper.

Making students better writers is (to me, at least) also simple: Get students to become better readers. Extensive reading is where I learned most my formal, passive vocabulary. It's where I learned where the commas go. More important, it's where I encountered things to write about and got the information to support whatever it was I had to say.

If I had a magic wand to turn students into omnivorous readers, I'd be rich and retired. Obviously, I'm not. Most of my students are a-literate (not il-literate), and too many of them actively resist anything and everything having to do with reading.

That's the real problem, but while I'm on a soapbox, I also want to say that it's nothing new and has very little to do with changes in our culture like TV, video games, or the internet. Students have always had trouble with academic writing, and teachers have always complained about it. Read what we had to say 30 or 50 or 150 years ago and see for yourself.

Dan Hemmens said,

September 26, 2011 @ 12:56 pm

I wonder if it was intentional, but I like how the first example substituting "sprinted" for "ran quickly" demonstrates the other endemic problem with usage advice.

I noticed that as well – a more specific word might be more flavourful, but it frequently isn't *right*.

Although in the example given, I would probably just say "ran down the street" since running is sort of quick by definition.

Ben Hemmens said,

September 26, 2011 @ 1:01 pm

>the long-standing and pervasive myth that English majors study the >grammar and linguistics of the English language?

Well, they may not study these things but some of the faculty try to teach them about them. My long-suffering spouse being a lowly member of such faculty, in a country that has no system of selection of students for subjects (indeed: anyone can study anything they want, the result is they have to fail about half the students by the end of the 2nd semester).

GeorgeW said,

September 26, 2011 @ 1:12 pm

Maggie Tallerman ("Understanding Syntax," 1998) says that 'tomorrow' is not an adverb as it does not take modifiers like 'very,' 'quite' and the like. It would be a noun functioning as an adverbial.

If the prosciption is against adverbials, the suggested PP would not work as well.

Theo Vosse said,

September 26, 2011 @ 1:30 pm

Here is a useful tool: a deterministic finite automaton that recognizes all English adverbs. Format is as follows: every record has a character, a flag, and a next state. If the flag is 1, and the word is finished, you've found an adverb. Otherwise, proceed to the state as indicated by the letter. If the letter is -1, go to the state mentioned when there is no matching letter. May this greatly improve your writing.

Janice Byer said,

September 26, 2011 @ 1:43 pm

Not an English major but ever the aspiring autodidact, I was delighted to pick up for 25 cents, some decades ago at a garage sale, a big old 1911 hardback titled "History of English Literature". The preface makes clear the text, published in NYC, was written by a professor at an American college. Only after I finished was it intriguingly clear that the domain of English literature for the author was works written by English writers not works written in English.

Theo Vosse said,

September 26, 2011 @ 1:51 pm

My post got lost, I guess due to the length. I had entered a (representation of a) deterministic finite automaton that recognizes whether a word is an English adverb or not. I built it a long time ago as a joke for a friend who was writing his thesis. It was embedded in a small C program that would mark up his LaTeX file. It greatly improved the thesis!

[(myl) Hi Theo! For some reason the length of your FSA code annoyed WordPress, which expressed its petulance by displaying your comment as literally empty of content, while retaining the content internally. I fixed (?) this by shifting the FSA listing to a separate file with a link.

If you'll send me the C code it was embedded in, I'll replace the FSA file with the source, and add a cgi script that will apply the code to supplied text.]

Jessica said,

September 26, 2011 @ 2:05 pm

I am, I think, living evidence to the comments by Spell Me Jeff and Philip. Both my parents are linguists, with a love for language that extends beyond the analysis of grammar to the joy of using it to communicate, and following their example, my early love for reading grew naturally into a love of writing. I learned English as any native speaker would – and despite several years of homeschooling, I don't remember any classes on grammar. My linguist parents didn't seem to feel that I would become a better speaker of English by being drilled in all the rules of the way my language works.

Surrounded by Spanish as a child as well, I learned Spanish through a mix of the "that just sounds right" method and, later, formal classroom teaching that explained more clearly why "it just sounded right." Since my Spanish was no where near as fluent as my English, the rules we were taught in high school were useful for the times when I couldn't just know instinctively what "sounded right."

In addition to being taught some basic grammar in Spanish classes, I was apparently in one of the few remaining public middle and high schools that considered "grammar" a core component of an English class. We took apart sentences, reviewed definitions of adverbs (an item on almost every grammar test I remember taking), and learned rules that more often than not sent me home frustrated to my parents with statements like, "Does it really have to be that way?" (Often answered with a comment like, "Your teacher doesn't realize language changes.") My English teachers, who did much to advance my abilities in reading and writing overall, taught just enough grammar to make me feel boxed in and confused. Thankfully, the books I read ("If a famous author can do that, why can't I?") and my parents' reassurance that there really were many appropriate times to break the "rules" of grammar I was being taught, enabled me to put those rules in context and not be afraid to play with language a little.

It wasn't until I started learning Chinese, however, that I discovered the actual power of teaching (and learning) grammar. Here was a language where I had no clue what "sounded right." At first, the grammatical basics (such as ordering nouns and verbs) were not very interesting. At that stage I was convinced Chinese grammar was really simple (after all, there were no pages of verb conjugation tables to memorize!). However, as the Chinese language became a living tool rather than an abstract concept, each new grammatical concept gave me a new sense of freedom as a whole new realm of communication possibilities opened up, and for the first time in my life I found myself actually excited to learn grammar.

As long as someone is trying to teach grammar to students who have already "internalized English grammar," as Philip said, it shouldn't be a surprise that students get bored. Literature majors don't need a list of grammar rules, unless they also plan on teaching English as a second language. In fact, if they are native English speakers, they could probably get by without a single grammar class at all. Most English majors I have known, however, do find grammar fascinating (often to their own surprise) – if, instead of being taught as a set of restrictive rules, it is taught as an exploration of not only the way language works, but also of how it is changing (and has changed) through time. But then, that is a perspective of grammar that most English teachers themselves never learned.

Chris Maloof said,

September 26, 2011 @ 2:25 pm

That's still the scholastic meaning of the term a century later, at least in America; English departments study any literature written in English, but English literature is only written by natives of England.

Jon Weinberg said,

September 26, 2011 @ 3:53 pm

On the relationship between grammar instruction and writing outcomes, I recommend Freddie deBoer's recent post "grammar and what can't be taught", at http://www.balloon-juice.com/2011/09/19/grammar-and-what-cant-be-taught/

Rodger C said,

September 26, 2011 @ 3:58 pm

@Spell Me Jeff: By "the cause of this" I meant the cause of grammar superstitions. I seem to have a habit of expressing myself too elliptically.

"[W]hat sounds right" is of very limited use if you're teaching Standard English as second dialect in Southeast Kentucky. As a general rule of instruction, it privileges the already privileged.

I thoroughly agree that the main cause of good writing in students is a lot of reading of something besides one another's text messages (Why does my spell check not recognize "another's"? A subject for another time …). But it's good to be able to have a vocabulary to talk about it.

Like Andy, I learned much more about grammar in Latin and Spanish classes than I did in English class. Needing the concepts to learn a language, instead of applying a strange vocabulary to the one I already knew, made sense finally.

Mel said,

September 26, 2011 @ 5:31 pm

What happened to Mad-libs? You have to know your parts of speech to play that properly and every book gave a brief explanation of them. My brother and a friend of ours used to put on plays using Mad-Libs that we'd filled in and memorized. Perhaps this would be a fun exercise for some age-groups?

John Lawler said,

September 26, 2011 @ 7:06 pm

After 4 decades of teaching English grammar (among other things) in a linguistics department at a large American university, I can say that the only American students entering my classes that understood anything about English grammar either: had taken Latin in high school

(and passed, which means that they had had to learn Latin grammar),

had lived abroad in a non-Anglophone area

(and learned the local language),

or

were not native speakers of English (and had perforce actually studied and learned real English grammar in order to learn the language).

These were all very smart and very motivated students, far above the national norms. But they mostly didn't know squat about grammar.

And why should they? Their teachers didn't, and neither did their teachers, unto the seventh generation. English grammar was never taught in English grammar or high school classes; one learned grammar by learning Latin. Then people stopped studying Latin, and all that was left was the catechism of shibboleths.

Take a look at http://www.umich.edu/~jlawler/1899MatriculationExam.pdf to see what one needed to know in order to get into college in a previous century.

Jonathan D said,

September 26, 2011 @ 7:50 pm

I attended a Strunkenwhitish writing course arranged by my employer, where we were actually told quite repeatedly that an aversion to adverbs was the cause of much bad writing in our context.

[(myl) Wait, you were told that your writing was bad because it didn't have enough adverbs? Sound like someone got the catechism backwards. Did they also tell you to remedy your deficiency in needless words?]

This post and discussion is made even more intriguing by the fact that I grew up with a high school English teacher with both English and linguistics majors for a mother.

Joshua said,

September 26, 2011 @ 9:03 pm

I'm surprised nobody has pointed out that the usage guide in the comic strip violates its own (ill-advised) rule: "There is no reason you should ever include one of these horrid monstrosities." In that sentence, ever is an adverb.

Janice Byer said,

September 26, 2011 @ 9:14 pm

"English departments study any literature written in English, but English literature is only written by natives of England."

Chris, thank you for the above clarification. It's my understanding that the English predominate cross-nationally lists compiled of the world's greatest men and women of letters; certainly they do American lists (as well as my little list of favorites), so it makes sense to me that they're as distinguished in curricula as in reality.

Philip said,

September 26, 2011 @ 11:36 pm

Roger C. and Andy report that what they learned in grammar classes didn't make sense until they studied Spanish or French or Latin. That's a common experience, too.

This is mostly singing to the choir, but books about English grammar didn't even exist until the 17th century. Educated people communicated across national boundaries in Latin. When the same educated elites began to write about English grammar, they assumed that because Latin had a certain structure, English must too. Of course, they were wrong: English is a Germanic language, not a Latinate language

Spanish and French, however, come from Latin. So it's no wonder that when English-speaking students begin to study Spanish or French, everything that didn't make sense in their English grammar classes suddenly does in Spanish class.

Here's an example: Latin has a present tense. Early grammarians assumed that English must also have a present tense. In the 21st century–"unto the seventh generation," as John Lawler says–grammar books teach students that "John leaves" is a sentence that contains a present tense verb, even though perfectly ordinary and everyday English sentences like "John leaves for Los Angeles tomorrow" or "John leaves for work every day at eight o'clock" are clearly something else.

So why do we continue with what Spell Me Jeff calls, wonderfully, a "catechism of shibboleths"? Mostly because English teachers know all about literature but very little about linguistics. And it's never easy, or even wise, to tell someone s/he's been misleading students for an entire career, even if (or especially if) you're right.

Justice4Rinka said,

September 27, 2011 @ 4:47 am

@ Spell Me Jeff

I suspect you are right. I learnt Latin at school from the age of 9 to 16. From this I found out things like what gerunds, subjunctives and so on were, in the sense that I found out the name of these constructions and tenses that I was already using. But lots of other kids sat through the same classes, and it did not follow that at 16 everybody had similar writing skills.

The likelier explanation is yours – that if you read a lot of the right sort of stuff, you absorb the right habits imitatively.

My parents and teachers were frequently exasperated at the stuff I put in compositions when I was 9 or 10. Typically I would write in whatever was the last style I'd read. If I'd just read some C S Forester or Jack London or the biography of Douglas Bader, that would be fine. If I'd been reading Jennings Follows a Clue or Billy Bunter, however, then whatever I wrote that week would be larded with obsolete schoolboy slang. I happened to find it funny, they thought it was irritating crud. Eventually I settled on something a bit better. I wonder what would have happened if I'd read Orwell at that age.

My 8-year-old has just finished reading the Harry Potters, but she's now quite happily listening along to her 5-year-old sister's Magic Faraway Tree bedtime stories. These ought to be a bit too young for her, but they are undemanding bedtime fare and grammatically sound, so it seems fine.

Justice4Rinka said,

September 27, 2011 @ 5:02 am

@ John Lawler

FWIW, some years ago I became frustrated at the illiteracy of university graduates my company was recruiting. We were a large consulting firm, and graduates would be assigned – more or less arbitrarily – to work on managers' projects.

Almost none of them could be relied upon to write a grammatical paragraph. These were people from prestigious universities in Europe, including the best ones.

I managed to get a literacy test introduced, in which the candidates were given a page of Orwell from which all the punctuation had been removed. They then had to put it back in so that it made sense. Any correct answer was acceptable, because clearly more than one is possible.

Initially, there was resistance to this idea from HR. They felt non-native English speakers would be unfairly disadvantaged.

How we laughed when the French, German, Spanish, and Italian candidates could all do the exercise without difficulty, while the native speakers uniformly could not. The non-Anglophones didn't even need to be able to understand the passage. They could figure out what was what in order to know how to punctuate it without needing to know what 'parody' or 'octopus' actually meant in their own language.

I'm in two minds about all this, because while I think clarity is important, I also 'get' that language changes. My concern, really, is when language changes because of ignorance, which in my view represents a progressive impoverishment.

Nick Lamb said,

September 27, 2011 @ 5:23 am

Andy, it's usually not helpful to compare human languages (even the constructed ones) to computer programming languages in this way. Computer languages were designed, in general their grammar actually exists as a formal specification. As a result it is usually fairly short. The back of Kernighan and Ritchie's masterpiece "The C Programming Language" contains the entire grammar of the language [as it existed in 1989] as just six pages of an appendix, almost an afterthought.

In any case, generally students aren't explicitly taught these grammars. It's not necessary, just as it isn't necessary in English. You don't need to be taught that "quickly" is an adverb to read Shakespeare or Capote and you don't need to be taught that "typedef" is a storage class specifier to read Torvalds or Chen. If there is some idea in the student's head that roughly corresponds to the category "storage class specifier" in the specification, very well, but there is no need to name it or study it for a general understanding.

greg said,

September 27, 2011 @ 7:25 am

"English departments study any literature written in English, but English literature is only written by natives of England."

I can't help but wonder how many "English literature" classes are actually British literature classes.

Rodger C said,

September 27, 2011 @ 7:31 am

@greg: Well, that's why we often refer to it as Brit Lit.

Rod Johnson said,

September 27, 2011 @ 7:57 am

I don't understand Theo's FSA at all, either as a joke or as a real thing. Can somebody help me out?

Spell Me Jeff said,

September 27, 2011 @ 9:00 am

Of course the "privileged" stay privileged by the system. No news there. My point here was not that "[W]hat sounds right" is of any particular pedagogical use. Far from it. Just that it's the way things work for the majority of students who end up being good writers. As others have mentioned, there is also overwhelming evidence that formal grammar instruction doesn't work for students who don't read. (John C. Mellon's 1969 NCTE monograph on sentence combining is a good place to start researching this issue.) Adding more formal grammar instruction doesn't help either. Indeed, it tends to worsen the problem. So the "privileged" continue to be privileged. And no, I'm not happy about that.

Janelle B. said,

September 27, 2011 @ 9:07 am

I have recently learned that, in AP style grammar, a "word, phrase, or clause" can be "restrictive or nonrestrictive", rather than simply applying to relative clauses as in the traditional usage of the terms, so that a name like "Madonna" can be considered nonrestrictive in a sentence like "That singer, Madonna, has written numerous hit songs." That usage made me doubt myself a bit when it came to the first quiz questions about that distinction, since I had been trained to look for a clause, not a name.

Rodger C said,

September 27, 2011 @ 9:34 am

@Janelle B: I'd think "Madonna" is in fact restrictive in that construction, and that the commas are therefore unnecessary, but one would have to see the context of the sentence.

@Spell Me Jeff: I don't remember ever asserting that formal grammar instruction did anything for students' writing. I don't in fact engage in it myself. You're still responding to your own misconstrual of my sentence.

I must say, though, that once on a slow day I diagrammed the two sentences "Time flies like an arrow" and "Fruit flies like a banana," and then the sentence "I saw her duck" two ways, for a Comp. 2 class, and got two distinct responses: groans from the students who'd been dragged through diagramming once on a time, and interest and questions from a couple of students, apparently engineering types, who were fascinated to be told, for the first time in their lives, that language had a structure.

At any rate, I teach at a federal work college whose avowed purpose is to provide opportunity rather than reproducing privilege, and "To him that hath shall be given" isn't good enough for me.

Faldone said,

September 27, 2011 @ 10:33 am

@Janelle B: I'd think "Madonna" is in fact restrictive in that construction, and that the commas are therefore unnecessary, but one would have to see the context of the sentence.

I would say that the phrase "That singer" implied a context that has already identified the singer although this might suggest that not only are the commas unnecessary but that "Madonna" is also.

Mary Bull said,

September 27, 2011 @ 10:42 am

I'm all for the suggestion that reading widely lays a foundation for good writing and would like to put in a plug here for the support of good teaching of reading in the early elementary grades. I wish this were better implemented in U.S. public schools.

Awareness that language has a structure could also be accomplished to some extent at this level, since reading and writing go hand-in-hand in most kindergartens and first grades.

(I'm one of the "English majors" commenting here, B.A. 1947, with an M.A. in elementary education that included a course in linguistics, ten years later. I taught high school freshman English for one year, and I soon concluded that the deficiencies I was seeing in my East Tennessee students needed to have been addressed much earlier, in first grade. So I then went back to school and subsequently taught 25 more years in several elementary schools in Kentucky, three of those in first grade and three as a "special reading teacher.")

I have discovered CGEL and later LL in my old age, and I really appreciate discussions like the one going on in the comments here.

Dan M. said,

September 27, 2011 @ 11:47 am

@Nick Lamb,

I think it's worth noting that your example of 'typedef' is a lot like what little Latin-based grammar that is taught in schools: wildly misleading to anybody who thinks that grammatical labels should actually describe how something works. There are several words in C that specify something's storage class (they're called storage class specifiers) by attaching a name to a type. 'typedef' attaches a name to a type and can occur in exactly the same places as a word that specifies storage class, but it doesn't do that! It defines a new name for a type, and the only relationship it has to other storage class specifies is that it fits in the same spot.

@Rod Johnson, Theo described a kind of computer program that provides a way of listing all the words in the English dictionary that are considered to generally be adverbs. I can't tell you whether this is in fact a joke or if he thinks that an (obfuscated) enumeration actually captures the grammatical category. But I also can seem to use the program on the ordinary word 'badly', so maybe I'm missing something too.

Janelle B. said,

September 27, 2011 @ 2:31 pm

@Rodger C & Faldone – You two just helped me realize an error that my instructor made in grading his quiz. Thanks! According to the AP grammar book, which I read over again upon seeing your comments, the name "Madonna" would, indeed, be restrictive in this case, and should not have the commas around it. Since there are, in fact, many singers that this sentence could pertain to, the artist's name IS necessary, according to the book. I thought there was something odd about that quiz item (which I, after all, did get right). Wow!

a George said,

September 27, 2011 @ 5:41 pm

I was just wondering, was the English major a cavalry major? And if so, what was her regiment?

WillSteed said,

September 27, 2011 @ 7:58 pm

It's important to distinguish between teaching grammar (i.e. how your language works – in essence, linguistics), teaching "style" (i.e. how to write clearly and relatively unambiguously, following the conventions of punctuation, etc.) and teaching "writing literature" (i.e. how to write things that people will read for pleasure).

The first is useful for understanding your own language and then learning others. It will also assist with the other two.

The second is useful for the workplace, essays, and for sounding intelligent. It will also help with the third.

The third, teaching how to write literature, is useful for people who want to write professionally. If you're writing a novel for people to read, many readers will prefer "He ran away" to "He moved away quickly", because of the imagery it creates, and because the brevity keeps a fast pace in the writing. This is also where the anti-passive hysteria comes from.

Applying the "rules" of writing literature (even if you acknowledge that there are many, many times when it's appropriate to break the rules) is more likely to confuse than to enlighten.

John Lawler said,

September 27, 2011 @ 8:24 pm

@ Philip: Not that there's anything important at issue, but I remember making up that phrase catechism of shibboleths several decades ago — nothing else seemed to fit so well — and using it frequently ever since, e.g:

http://groups.google.com/group/alt.usage.english/msg/111584f741a99f79

http://linguistlist.org/ask-ling/message-details1.cfm?asklingid=200335466

http://www.umich.edu/~jlawler/aue/itsraining.html

http://www.umich.edu/~jlawler/June05Eye.pdf

Rodger C said,

September 28, 2011 @ 8:17 am

@a George: The Monstrous Regiment of Women, of course.

Colin said,

September 28, 2011 @ 10:24 am

I remember failing a test in English grammar in junior high, despite having by that point two years of Latin grammar, and no difficulty writing English due to the advantages Jeff lists. Kids who read less than I did found it much easier to dissect English sentences and label speech parts; I couldn't make the switch.

Jason Orendorff (@jorendorff) said,

October 1, 2011 @ 3:11 am

Now hang on a second, Mark. Doesn’t CGEL call yesterday and tomorrow pronouns?

As evidence, they’re substitutable for the days of the week (which are proper nouns); they can serve as subject of a sentence (Tomorrow would be ideal.) or the object of a preposition (I can wait until the meeting / April / tomorrow); and they have genitive forms (Tomorrow’s special will be chicken cacciatore.)

Jonathan said,

October 1, 2011 @ 5:28 pm

The English department should be abolished. Undergraduates should have to choose between two majors: Latin or physics.