Just all this math, filling up the page

« previous post | next post »

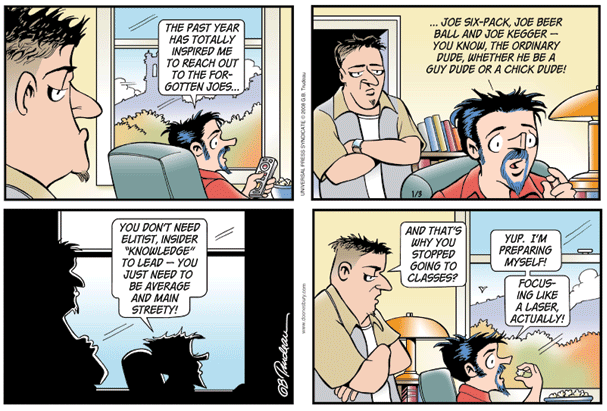

Zipper has found his vocation:

And after he graduates, he can get a job in journalism.

Here Jon Stewart explores a real-world case — the efforts of Gretchen Carlson, with her Stanford honors degree, to pretend to learn the meaning of words like "ignoramus" and "czar" (the relevant part starts around 2:35):

But it's not just Fox News whose reporters use ordinary-Joe ignorance as a rhetorical strategy. Listen to NPR's "Planet Money" team, Adam Davidson and Alex Blumberg, dealing on New Year's Day with the question "Can Economic Forecasting Predict The Future?". The context is a serious one, as Steve Inskeep explains:

The consensus among leading economists, for what it's worth, is 2.7 percent growth this year – not so great, not horrible. That's the forecast. NPR's Planet Money team has been studying just how the business of economic forecasting works and how much it can actually tell you about the future.

And the intrepid Planet Money team's "studying" has achieved a laser-like focus comparable to Zipper's and Gretchen's. Here's the start of their visit with Joel Prakken, the creator of the economic forecasting program at Macroeconomic Advisors.

ADAM DAVIDSON: The closest thing to a modern day financial oracle is probably a computer program that lives in St. Louis, Missouri. That's where the offices of Macroeconomic Advisors are located, one of the leading economic forecasters in America. Joel Prakken, the man who created the computer program, showed us on a computer screen how it works. […]

The basic idea here is pretty simple. Take economic data from the past and use it to predict what will happen in the future. That's where Prakken comes in. For the past 28 years, he's been figuring out the exact relationships between different kinds of economic activity.

ALEX BLUMBERG: If average salaries go up by, say, four percent, how many more cars will people buy with their new, bigger salaries? What will all that spending do to the inflation rate, and what will the inflation rate do to home sales? And how will home sales, in turn, affect salaries? It's all connected, and Joel has written down exactly how it's all connected in a series of equations.

Mr. PRAKKEN: If we scroll down a little bit further to look at some of the equations of ours…

BLUMBERG: Oh gosh. [laughs nervously]

Mr. PRAKKEN: Yeah, okay. So- here is an equation – yeah…

BLUMBERG: Oh, my God. Whoa, it gets worse every page.

Mr. PRAKKEN: It does get worse.

BLUMBERG: We're looking at a screen that is full of really long numbers and Greek symbols and just all this math filling up the page.

Now, now, I just want to point out, also, so this one page here, there are – what? I'm looking at the four hundred…

Mr. PRAKKEN: You're on page forty nine of four hundred and forty seven.

DAVIDSON: Four hundred and forty seven pages of really dense math equations. That's how you forecast the economy.

Well, that certainly clears everything up! You can listen to the whole piece here, but I've pulled out the crucial bit in case you want to download some choice phrases into your talking Ken doll:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

As Barbie famously didn't say, "Math is hard, let's go reporting!"

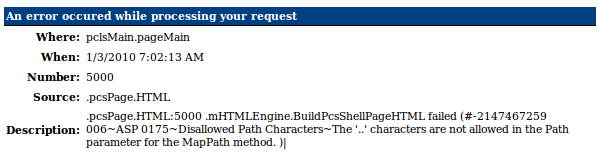

By the way, for the past few days, the front page of the website of Dr. Prakken's company, http://macroadvisers.com, has looked like this:

I'm not certain that this is connected to the visit of the Planet Money team, but surely it's not a good sign.

But if you search past the damaged front page, you can find useful things like this tutorial, "Structure of the Macroeconomic Advisers’ Macro Model of the U.S. Or How to Make an Honest Living Pushing Around Big Matrices of Helpless Numbers". You'd need to have taken an economics course or two to explain it to a general audience, though. Gretchen? Zipper? Anybody?

[Seriously, Davidson and Blumberg did a great job on their This American Episode segment "The Giant Pool of Money". But there, they got away with ignoring all the math above the level of percentages, because all the math above the level of percentages (the equations behind those credit default swaps and such) was pretty much smoke and mirrors, and the real story was the greedheads who hired the quants to model a world that didn't exist, and the fools who believed their pitches, and on down the line. So when D&B reduced the housing bubble to a simple morality tale about greed and gullibility, it worked.

But here, when you toss out the mathematical modeling to get down to the story underneath it, there's nothing much left. Either these guys were completely out of their depth on this story, or they were just phoning it in. Or they were trying to make a point, reinforced by the folderol about economic estimate updates in the next segment of their piece — "None of those economic modelers actually know anything, it's all just a bunch of greek letters and fuzzy numbers — you might as well ask your taxi driver".]

[Update — the New Year's Day Planet Money segment on Morning Edition, which this post is based on, appears to be a shortened form of a longer This American Life segment, which is being broadcast for the first time today (at least on my local station). In this longer version, D & B boggle at greater length over the math (some Greek letters and negative numbers are read out loud, and one of them expresses amazement that the other one remembers that a capital Sigma means that you add stuff up) — but in the end, they do manage, against the odds, to reduce econometrics to psychodynamics. The trick is to spend several minutes on an in-depth discussion of how forecasters hate to admit that they're wrong, even though they can't avoid being wrong to some extent… As far as I can tell — I missed some parts of the live segment — there's no real discussion of what the models are really doing, which (as far as I understand it) is complicated mainly by virtue of having lots of moving parts, each of which is in fact pretty simple. More analysis once the audio and transcript are available.]

tablogloid said,

January 3, 2010 @ 11:38 am

How may I contact Joe Luddite?

Dan Lufkin said,

January 3, 2010 @ 12:57 pm

The Planet Money situation is precisely like that of the climate-change "controversy." Understanding the physics behind the greenhouse gas phenomenon involves understanding S. Chandrasekhar's Radiative Transfer, almost 400 pages essentially of equations. It took about 10 years to get radiative transfer running on some giant computers. The programs have been freely available for years, but the recent e-mail flap made a lot of skeptics demand to inspect the code for fraud. Imagine their dismay when they got a couple hundred pages of Fortran that no individual fully understands.

The underlying problem in both economics and climatology is that we're dealing with phenomena that are far too complex for humans to understand intuitively, but too important to our civilization to be left to computers alone. I haven't the faintest idea what the solution is. I sure hope Zonker stumbles onto it.

Ran Ari-Gur said,

January 3, 2010 @ 12:59 pm

It's nice at least that Gretchen Carlson purports to get her information from dictionaries and Googling, rather than from (say) interviewing an expert: she's being disingenuous, and that's a very disturbing thing for a news analyst to be, but at least she's promoting the notion that meaningful political and economic information is readily accessible to laymen on our own terms. That's a lesson that many people seem to have not yet fully absorbed.

Mark P said,

January 3, 2010 @ 1:29 pm

As I have said before, journalists are, as a group, the worst educated of all professionals. And I say that as a former journalist.

@Dan Lufkin- I disagree that it's necessary to take a graduate course in atmospheric radiative transfer to get a basic understanding of the greenhouse effect. I think it's possible to explain it in layman's terms with reference to only a few physical principles. But very few people, especially among the masses who follow the intentional misrepresentations of the deniers, are interested in listening to even simple explanations. But even if the basic principles are fairly easy to understand, it's much harder to understand how those principles and all the equations behind them can be transferred to a climate model; understanding climate modeling really does require a good background in all the principles, and not just radiative transfer.

Melissa said,

January 3, 2010 @ 3:34 pm

In my experience, the Planet Money guys do a good job looking out for the listener when a guest uses any terms that listeners might not know or remember. As an engineer with a mortgage I get most of the basic financial stuff they talk about, but since I listen while cooking I still appreciate the explanations/reminders they throw in to make it easy to follow.

I suspect maybe Adam Davidson & Alex Blumberg would have gotten more into the math, but it was decided (by them or their boss) that the psychodynamic angle was the best story for the blog. As supporting evidence I submit the fact that Chana Jaffe-Wolt was hired onto the Planet Money staff; she excels at the psychology/sociology angle. It seems like we've been hearing fewer stories from Adam, who is a longtime business reporter and apparently the most technical on financial matters.

Then again, I've heard them point out financial stuff that doesn't make intuitive sense to their colleague David Kestenbaum, who has a PhD in physics, so maybe they do think the math is too difficult to bother with.

Even when Planet Money has extraneous explanations, I don't feel patronized. It doesn't bother me like Gretchen Carlson's purported ignorance of basic vocabulary. Also, it seems like part of her googling schtick is linguifying, doesn't it? She needs some angle to discuss the issue, why not use a definition from an external source?

Dan Lufkin said,

January 3, 2010 @ 4:34 pm

@Mark P — You're exactly right, the climate model is the most difficult part. [Disclosure; I worked in the Arrhenius Lab in Stockholm back in the 60s; Bolin was my thesis advisor and I shared an office with Dave Keeling.] The radiatiative transfer phenomena, though, determine the magnitude and distribution with pressure of the radiative heating and tie the whole mess to CO2. It's this last step that is the most critical in dealing with skeptics, the more thoughtful of them, anyway. (That amounts to about 2% of them.)

We prolly ought not to get LL involved with the No. 1 tar-baby of science policy.

Bloix said,

January 3, 2010 @ 6:01 pm

Virtually nothing that science has produced since Newton and Galileo can be "understood intuitively." Things that can be understood intuitively are wrong. The earth stands still while the sun goes up and down. Moving objects slow down and stop on their own. Heavy objects fall faster than light ones. In order to understand anything that's not wrong, you need some mathematics. Not so long ago, everyone with an education understood that.

What's going here is that cool kid anxiety has permeated the culture to such an extent that if you admit that you actually understand anything, you're branding yourself as a fag. The phony math anxiety of the Planet Money guys is actually a sexual anxiety.

Douglas McClean said,

January 4, 2010 @ 9:14 am

@tablogloid,

I believe he can be reached at joe.the.luddite@geocities.com.

Maria said,

January 4, 2010 @ 12:59 pm

I'm an economist, and I don't know how I'd explain the macroeconomic forecasting process with any sort of accuracy in a limited time frame. Not just to a lay audience – to an economist who does not do macro. These models usually have assumptions about how the world works that make little sense to the uninitiated, and what set of assumptions you choose is undetermined. I thought they did a good job… the part where they say

is a good explanation of how these models work. The "pages of math" come from having many products and variables whose paths have to be determined, and the interplay between them. I don't see what would be gained by discussing if you need to include a quadratic term, or whatnot.

[(myl) If that's true, then it might have been better just to leave out all the nervous laughter over equations and greek letters.

But in fact, I bet that you could do a good job at explaining one selected piece of the network, focusing on the choices to be made about the functional form of the connections, the time delays involved, the effects of feedback from selected other factors, and so on. Then the rest of it is just a lot more of the same.

That would allow you to make the point that "the set of assumptions you choose is underdetermined", in a concrete and specific way. Or you could leave the description vague, as in the passage you quote. But what's gained by making the discussion more concrete would be giving a concrete sense of what the choices are (what factors and interactions? what functional forms? what coefficients?), and how different modelers decide what choices to make, and how much difference their choices make.

In either case, all the "OMG! Whoa! Math!" stuff delivers a disjunctive message: This is Really Complicated Math Stuff and so the experts must be right; or This is Really Complicated Math Stuff that has nothing to do with real life. Both messages are wrong, it seems to me.]

Josh said,

January 4, 2010 @ 2:38 pm

I've noticed this same phenomenon with the various science programs on networks like The History Channel and The Discovery Channel. They will shy away from the why and the how and just focus on how huge the machine is or how smart the scientists and engineers must be to figure out all that math, implying it's beyond the capabilities of mere mortals. Contrast that with programs like Nova and Nova Science Now on PBS. These programs still simplify concepts so that a layperson can make sense of them, but they don't shy away from difficult concepts. They've had some fantastic programs on Relativity, nuclear physics, astronomy, biology, and more that do a great job of explaining the concepts involved and illustrate the the difficulties involved and the things we still don't completely understand.

Forrest said,

January 4, 2010 @ 5:41 pm

I heard the segment on Seattle's KUOW. As this posting alluded to, the following radio segment was about the uncertainties of economic forecasting. I don't remember the quotes word-for-word, but what stood out in my mind was something along the lines of "If we can't predict what happened in 2007 until the end of 2010…" So maybe some of the "gee, whiz" stuff was rhetorical, to make this point stronger.

It would have been interesting to hear why we make this series of ever more accurate predictions about the past until "finally giving up." Is it that we don't have the numbers for Joe the Fruit Mogul's lemonade stand? Or is it that we don't fully understand what conclusions to draw from the numbers?

[(myl) I felt that the failure to clarify the reasons for repeated updates of past economic estimates was one of the biggest weaknesses of the segment.

There are some relevant links here, including especially Dean Croushore and Tom Stark, "A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Data Bank: A Real-Time Data Set for Macroeconomists," Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Business Review, September/October 2000. They give various reasons for revisions, including incomplete data (thus 2009 is over, but income tax returns for 2009 won't even be due until April 15, 2010), There are also revisions in the definitions of the variables involved, such as the sources of information used to estimate them, and the methods used to create the estimates. Croushore and Stark describe how the estimate of the "growth rate of real output" for the first quarter of 1977 started at 5.2% in May of 1977, and then changed because of additional data to estimates of 7.5% in August of 1977, 7.3% in August of 1978, and 8.9% in August of 1979. Then a "benchmark revision" (i.e. a methodological change) in late 1980 resulted in an estimate of 9.6%, and another change in August 1982 brought the estimate down to 8.9% again, where it stayed until another benchmark revision in 1985 changed the estimate to 5.6%, and another one in 1991 nudged it up to 6.0%. In February 1996, it came down to 5.6%, and then in 1997 to 4.9%, and in 2000 to 5.0%. It would nice to learn something more about how and why these changes happen.]

Alex said,

January 4, 2010 @ 7:09 pm

"In either case, all the "OMG! Whoa! Math!" stuff delivers a disjunctive message: This is Really Complicated Math Stuff and so the experts must be right; or This is Really Complicated Math Stuff that has nothing to do with real life."

The messages it delivers to me are:

This is Really Complicated Math Stuff and so aren't to be worried about by the proles; or This is Really Complicated Math Stuff and Real Americans should find it bizarre.

A.C. said,

January 5, 2010 @ 5:02 pm

@ Bloix: "What's going here is that cool kid anxiety has permeated the culture to such an extent that if you admit that you actually understand anything, you're branding yourself as a fag."

Well, not necessarily. Many (say) climate change denialists or Einstein "debunkers" try to cast themselves as "hardy skeptics and true scientists fighting The Establishment" and do that by parroting what public sees scientists do in popular media. That is shouting "Eureka!" and then explaining their (faux) findings in analogies, fables, and just-so stories.

Yet another part of it is that even when real math and hard evidence are clearly on the one side, and even if they're explained, you (the layman) need to experience for yourself that properly applied math works much better than a "no formulas" analogy. Or else it would be just another way to tell a different set of just-so stories. Most scientists, of course, have such an experience, but most of the general public never did. And thus they don't see wgy scientific account should be more trustworthy than anything else.

Sorry for any weird English, I'm not a native speaker.

uberVU - social comments said,

January 9, 2010 @ 11:12 pm

Social comments and analytics for this post…

This post was mentioned on Twitter by PhilosophyFeeds: Language Log: Just all this math, filling up the page http://goo.gl/fb/NWso…