The business of newspapers is news

« previous post | next post »

At the Atlantic, David Shenk mediates an exchange of letters between Mark Blumberg and Nicholas Wade about the appropriateness of calling FOXP2 a "speech gene", about "gene for X" thinking in general, and about the nature of science journalism:

Blumberg: Trumping up FOXP2 as yet another star gene in a series of star genes (the "god" gene, the "depression" gene, the "schizophrenia" gene, etc.) not only sets FOXP2 up for a fall; it also misses an opportunity to educate the public about how complex behavior – including the capacity for language – develops and evolves.

Wade: I'm a little puzzled by your complaint, which seems to me to ignore the special dietary needs of a newspaper's readers and to assume they can be served indigestible fare similar to that in academic journals. […]

As for missing an opportunity to educate the public, that, with respect, is your job, not mine. Education is the business of schools and universities. The business of newspapers is news.

I'm glad we got that straightened out!

Read the whole exchange between Blumberg and Wade here.

For some background, see the discussion and links in "The hunt for the Hat Gene", 11/15/2009.

And as part of my job of educating the public, let me draw your attention to some scientific news announced in a recent paper by M R Munafò et al., and as far as I know not covered by any newspapers ("Bias in genetic association studies and impact factor", Molecular Psychiatry 14: 119–120, 2009):

Studies reporting correlations between genetic variants and human phenotypes, including disease risk as well as individual differences in quantitative phenotypes such as height, weight or personality, are notorious for the difficulties they face in providing robust evidence. Notably, in many cases an initial finding is followed by a large number of attempts at replication, some positive, some negative. Although there has been debate over the statistical arguments concerning the strength of evidence in association studies, there has been less interest in understanding why it is that some genetic associations generate such large literatures of inconclusive results. We wondered whether one source of the difficulties in the interpretation of genetic association studies might lie with the journal that published the initial finding. Studies published in journals with a high impact factor typically attract considerable attention. However, it is not clear that these studies are necessarily more robust than those published in journals with lower impact factors. […]

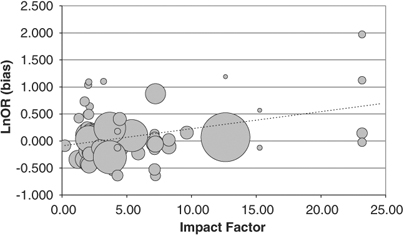

Data were analysed using meta-regression of individual study bias score against journal impact factor. This indicated a significant correlation between impact factor and bias score (R2=+0.13, z=4.27, P=0.00002). Our results are presented graphically in Figure 1. We also note that journals with high impact factors tend to publish studies with high bias scores and small sample sizes (as indicated by the smaller circles in the figure).

Here's Figure 1 and its caption:

Meta-regression of individual study bias score and journal impact factor. Bias score is plotted against the 2006 impact factor of the journal in which the study was published. Meta-regression indicates a positive correlation between journal impact factor and bias score (R2=+0.13, P=0.00002), suggesting that genetic association studies published in journals with a high impact factor are more likely to provide an overestimate of the true effect. Circles, representing individual studies, are proportional to the sample size (that is, accuracy) of the study.

In other words, the more prestigious the journal (as measured by its "impact factor"), the less likely the genetic association studies it publishes are to be replicated.

If I were merely in the business of news or entertainment, I'd observe at this point that the particular FOXP2 study behind the Blumberg/Wade discussion was published in one of the highest-impact-factor journals in the world, Nature, and thus is statistically somewhat more prone to fail to replicate than if it had been published (say) in Prof. Blumberg's journal, Behavioral Neuroscience.

But this would be unfair. Details aside, the paper's conclusion (that the two different amino acids in the human-specific version of FOXP2 cause "differential transcriptional regulation in vitro" of a very large number of other genes) is surely true; and the detailed claims about the genetic networks involved may well turn out to be helpful in understanding how the capacity for language develops and evolves.

However, we can also be fairly confident that calling FOXP2 a "speech gene" — and the whole "gene for X" style of thinking that this exemplifies — will become more and more clearly a source of confusion. In my earlier post, I quoted Simon Fisher (the scientist who first discovered the connection between a FOXP2 mutation and a syndrome that includes some speech-related disabilities):

[T]he deceptive simplicity of finding correlations between genetic and phenotypic variation has led to a common misconception that there exist straightforward linear relationships between specific genes and particular behavioural and/or cognitive outputs. The problem is exacerbated by the adoption of an abstract view of the nature of the gene, without consideration of molecular, developmental or ontogenetic frameworks. […] Genes do not specify behaviours or cognitive processes; they make regulatory factors, signalling molecules, receptors, enzymes, and so on, that interact in highly complex networks, modulated by environmental influences, in order to build and maintain the brain.

At some point, I guess, this will become not merely truth, but also news.

Mark P said,

December 10, 2009 @ 11:34 pm

"The business of newspapers is news."

What a quaint fiction. I'm sure it's believed by many J-school graduates for months, if not a couple of years, depending on where they work. In my own experience, which I believe is not too unusual, we were free to find and report on anything as long as it didn't step on any toes that the owner or publisher valued. Thus I was left to conclude that the business of newspapers is business.

Ray Girvan said,

December 10, 2009 @ 11:53 pm

Mark P: Thus I was left to conclude that the business of newspapers is business

Covering Science: Why the Media So Seldom Get It Right has a good analysis of that: how papers are financially shackled into printing what matches the prejudices and desires of their readers. Folk want formulaic certainties from science stories – definite cure found for X, definite cause found for Y.

John Cowan said,

December 11, 2009 @ 12:12 am

My favorite example of a bogus "gene-for" is RP1, the gene for reading. If your RP1 is defective, you can't read, so that shows that reading is an inherited ability, which means there's not much point in improving how it's taught, right?

(What it actually does when defective, of course, is to give you retinitis pigmentosa, which leads to blindness — so obviously you can't read. Braille? Doesn't count. The obvious fact that many genetic disorders can be mitigated by environmental changes? Contrary to dogma.)

Chris said,

December 11, 2009 @ 1:29 am

For better of worse, we silly humans are addicted to an "X causes Y" logic (regardless of how complicated actual causation might be). By default, we prefer an explanation of events that involves as few actors as possible and as direct influence as possible in time and space. Unfortunately, reality rarely follows this formula. Therefore, we prefer non-reality. Any journalist willing to feed us a neat, cause-and-effect explanation will likely be rewarded with popularity (Malcolm Gladwell, I'm staring at YOU). It's tough to tell people that the world is not the way they think it is. I wish more journalists would do this, but they're not paid to challenge their readers; they are paid to placate them.

Dierk said,

December 11, 2009 @ 6:26 am

The news is newspapers' business – regardless of the truth value of what is reported? That is, print and broadcast anything you haven't heard before, never ask if it is true, never try to explain what the actual contents of a "news" is. I like that.

May I ask why so many newspapers, magazines and TV news shows have nothing to do but rehash olds – like Tiger Woods' driving skills or Barack Obama's birth certificate?

Ah well, at least Wade cleared one thing up: F… the readers/audience, we say something half-digested, making it unintelligible and leave it to the customer to get the proper education from difficult to understand technical papers in scientific publications. Gotta love "journalists".

Liz said,

December 11, 2009 @ 7:40 am

Not at all sure about this, but aren't the origins of newspapers somewhere between polemic, propaganda and entertainment of a fairly sensationalist nature, and the idea that they dealt with news a late and short lived phenomenon? Thinking of 19th and early 20th century wars, mainly. Maybe it is shifting and imprecise meanings of the word "news" itself that are the problem?

[(myl) His aphoristic defensiveness aside, Mr. Wade has a point: journalists have the nearly impossible task of being brief, true, clear, and interesting. It makes their lives easier to portray research (or politics) in terms of simple ideas that their readers already understand, such as a one-to-one relationship between genomic variants and phenotypic traits. Individual journalists tend to have favorite narratives, and it seems that the "gene for X" idea is Wade's standard frame for many of the discoveries of modern molecular biology, which he carries over into his interest in evolutionary psychology. The problem for the rest of us is that some of these simple ideas are false, or irrelevant to the story at hand, or even socially pernicious.

This is not a new problem, and the process doesn't (it seems to me) work very differently in periodicals that are focused on entertainment or on propaganda. For that matter, a similar process of creating, maintaining and using shared stories is at work in scientific communication as well. But among scientists, it's common to break in and say "wait a minute, you're assuming something here that's not true, and it's leading you off in the wrong direction". Such interventions are often denied or ignored, rightly or wrongly. And often the answer is "you're right in principle, but our little fiction allows us to get on with our work, and doesn't materially affect our conclusions". Russell Gray is fond of expressing this idea by adapting to science Picasso's assertion about art: a model is a lie that leads us to the truth.

Nicholas Wade might have used a defense of this type: newspaper readers need simple and clear story lines, and "gene for X" is an over-simplification that helps them to understand results that would otherwise be too complex to attend to. Prof. Blumberg disagrees — he thinks that "gene for X" is a lie that leads away from the truth, not towards it. That sort of disagreement is normal, but rather than engaging the objection, Wade suggests that the choice of framing narratives for the "news" about science is his business, and mere scientists should butt out and leave the news to experts.]

Michael Farris said,

December 11, 2009 @ 9:07 am

The business of newspapers has traditionally been selling ad space as that's where their profits (when they existed) came from. Maintaining readership is just a means toward that end.

Picky said,

December 11, 2009 @ 9:23 am

Selling ad space – well, yes, but if we're talking about The Truth we should admit that that's an over-simplification worthy of a journalist (admission: I receive a pension from a news organisation). Newspapers have also been owned and run for political influence, or to boost an owner's social standing (in the UK sometimes as a route to a peerage), or even for the supposed good of a community or similar lofty ideals. If profit were always the only criterion, we wouldn't have, for instance, the Scott Trust.

Mark P said,

December 11, 2009 @ 9:39 am

I was about to make a fairly long comment, and then realized I was just restating myl's comment above. I think it pretty much nails it.

Carl said,

December 11, 2009 @ 9:49 am

Leaving the business of newspapers aside, I was fascinated by the quoted observation that "the more prestigious the journal (as measured by its 'impact factor'), the less likely the genetic association studies it publishes are to be replicated"! Not having access to the original article in "Molecular Psychiatry", I wonder whether the authors suggest any explanations for the phenomenon. Perhaps researchers are nervous about attempting to test results already published in prestigious journals? Who knows!? Interesting, though. I suppose that such a phenomenon would be necessarily limited fields in which research is based on experimentation, but I wonder whether the same phenomenon would be found in other fields as well. (It wouldn't surprise me, perhaps …).

[(myl) By "not replicated", I meant that replication was tried and failed. A clearer way of stating the point would be "the more prestigious the journal, the more likely the (genetic association) studies it publishes are to turn out to be false".

The explanation, as I understand it, is that high-impact journals want high-impact papers; the rest is a natural consequence of the phenomenon known as "regression to the mean".

As the authors explain,

]

Sili said,

December 11, 2009 @ 10:00 am

And for papers business means advertising. The only reason that there's anything but ads in the papers is to give people the illusion that they're worth paying for.

Sven said,

December 11, 2009 @ 10:08 am

So someone ran a linear regression against those blobs which represent somewhat subjective measurements (i.e. not readings of a meter) *and* finds a dependency? From that plot? Without reporting errors (or did I miss those)? I haven't read the linked paper but I don't suppose it's meant to be a joke.

[(myl) No, there's nothing subjective here. The studies in question deal with allegedly significant genotype/phenotype relationships, and later studies may succeed or fail in confirming the relationship. As the authors explain:

Those "odds ratios" are parameters that emerge from the statistical analysis that all genetic association studies use to determine whether a particular genomic variant has a significant association with some phenotypic characteristic. So the question is, how does the first study's number compare to the pool of numbers from the series of studies that attempt to replicate the original finding? A value of 0 means that the subsequent studies are equally likely to find the association to be stronger or weaker than the first one did. A negative value means that subsequent studies find that the first study underestimated the strength of the association. A positive value means that subsequent studies find that the first study overestimated the strength of the association.

The finding is that studies published in more prestigious journals tend to overestimate the strength of genotype-phenotype associations, at least in the collection of cases considered.]

The reason I jump at this is having seen a few medical reports recently about vaccine testing (you can all guess what they were for…) that claimed to see effects from "measuring" fatigue, pain, and other subjective data in a sample size of 50. All of which they reported without the most basic error estimate.

[(myl) As I explained, this paper is entirely based on the statistical measures of strength of genotype/phenotype association in the designated segment of the literature. The only subjective part of it is the medical diagnosis involved in the phenotype-classification aspect of the original papers.]

Bloix said,

December 11, 2009 @ 10:33 am

The Washington Post is in "the business of putting out opinion," even if it's full of lies. http://mediamatters.org/blog/200912100046

Ginger Yellow said,

December 11, 2009 @ 10:42 am

Not at all sure about this, but aren't the origins of newspapers somewhere between polemic, propaganda and entertainment of a fairly sensationalist nature

Origins? That's how they still are in the UK.

Besides, even if you accept that the business of newspapers is news (and as a journo I do, if only in an idealistic sense), how are you supposed to convey the news about a complex subject if you don't educate your readers in the process? I've noticed that many American print journalists seem to have an deep-seated aversion to ensuring that their readers have enough context to understand a given news event, and I don't really understand it. Maybe they think it blurs the line between supposedly objective hard news and more subjective analysis, but even so, surely if your readers don't understand what exactly has happened at the end of a news story, you've failed.

Richard Hershberger said,

December 11, 2009 @ 10:49 am

My take on the exchange is that good popular science writing is difficult. From my youth, Isaac Asimov was terrific at it. In my maturity, Stephen Jay Gould stood out. Both were scientists who branched out to popular writing. (At the risk of causing eyes to roll, Steven Pinker is also quite good at this, and has terrific hair!) I have seen some good popular science writing by people approaching it from the popular side, but it is perhaps significant that none really stand out.

The task of taking complex ideas and making them understandable to the general reader without too much distortion and within a reasonable word count is obviously non-trivial. I am willing to cut some slack on a honest failure. But Wade seems to have given up on the idea, if he ever had it, and embraced simply making shit up for a good story. feh

sls said,

December 11, 2009 @ 11:12 am

Chris:

"For better of worse, we silly humans are addicted to an "X causes Y" logic (regardless of how complicated actual causation might be). By default, we prefer an explanation of events that involves as few actors as possible and as direct influence as possible in time and space."

I'm sure there's a gene that determines that. =)

Ginger Yellow said,

December 11, 2009 @ 11:55 am

The task of taking complex ideas and making them understandable to the general reader without too much distortion and within a reasonable word count is obviously non-trivial. I am willing to cut some slack on a honest failure. But Wade seems to have given up on the idea, if he ever had it

Yeah, this is the key. I'm not claiming its easy to convey complex science in a news story. But it's essential to try.

Acilius said,

December 11, 2009 @ 12:01 pm

@Richard Hershberger: I usually hate THE NEW YORK TIMES, and I certainly agree that Wade has done a thorough job of making an ass of himself in this case. Also, it's true that he not only has a lazy habit of writing "gene for x" stories, but also he tends to sneak nativist hypotheses in to explain ethnic differences that may be environmental in their origin (doubtless these are the "socially pernicious" remarks Mark had in mind in his response to Liz above.)

For all that, I think he's one of the better science reporters around. I just wish he had a tougher editor, and of course that he had kept his cool rather than say something as stupid as what is quoted in the post.

John said,

December 11, 2009 @ 1:01 pm

Bloix- the piece you linked to was on the Op-Ed page, which I have always understood to be opinion, not news.

On the other hand, Fox successfully defended a whistle-blower case claiming that the FCC "news distortion policy" is essentially only a guideline, and that the law does not actually require news to be truthful.

John said,

December 11, 2009 @ 1:01 pm

(That's Fox News, not FOXP2)

fev said,

December 11, 2009 @ 1:47 pm

Yeah, since the person who says "we are in the business of putting out opinion" is the op-ed editor, I'd say it's safe to infer that she's talking about the op-ed pages, rather than the whole of the paper.

The FCC deals with broadcasting, not with news in general. The First Amendment provides an unbreakable shield for the right of newspapers to screw things up.

Forrest said,

December 11, 2009 @ 2:20 pm

An earlier post here talked about the same thing – in that case, I think the explanation given was that journals like Science, Nature, and the like, have more papers submitted to them, and are more likely to print the more eye-catching ones.

Chad Nilep said,

December 11, 2009 @ 3:21 pm

As others have noted, Mr. Wade's argument may be roughly paraphrased as, "It is my job, as a science journalist, to inform my readers in broad strokes, not to educate them as to fine detail."

Curious, then, is his claim regarding "Paabo's paper" (maybe Enard et al. 2009?).

Wade writes, "I think most people would say the experiment was important and needed to be done, even if we don't really understand yet what all the changes mean. That's why I thought it was worth writing up."

The study may be important to geneticists and biologists, but is it important to Wade's audience of New York Times readers who cannot "be served indigestible fare similar to that in academic journals"?

Bloix said,

December 11, 2009 @ 3:45 pm

The Post has a habit of publishing lies on the op-ed page and then saying, hey, those lies in the George Will/Michael Gerson/Charles Krauthammer/Sarah Palin/Robert Kagan piece aren't really lies, they're opinion, because they're printed on the second-last page of the A section. A statement doesn't stop being an assertion of fact, subject to the test of truth or falsity, just because it's printed under a by-line at the back of the paper.

Coleslaw Praisebroccoli Kohlsen said,

December 11, 2009 @ 4:02 pm

Andrew Robinson writes outstandingly good popular

books on a range of scholarly topics. He has research

grants, so he might be an academic as well as a journalist.

But he definitely has the gift of taking the topics and

making them digestible.

http://www.andrew-robinson.org/books.html

CBK said,

December 11, 2009 @ 9:01 pm

Perhaps Munafò et al.'s study could be publicized by referring to the "file drawer effect" a.k.a. "publication bias." Wikipedia describes this as:

"the tendency for researchers, editors, and pharmaceutical companies to handle the reporting of experimental results that are positive (i.e. they show a significant finding) differently from results that are negative (i.e. supported the null hypothesis) or inconclusive."

One might consider a file drawer as a very low-impact form of publication. (It's not necessarily zero impact, some people do pass unpublished articles around.)

Jesse Hochstadt said,

December 12, 2009 @ 9:09 pm

@CMK: And of course publication bias in research journals would tend to exacerbate the bias toward "sensational" findings in the popular media.

On the topic of complex, um, chains of causation, I once walked into a neuropsychology class I was teaching and said: "I'm really annoyed. I was riding my bicycle yesterday when I found I was still pedaling but the bike wouldn't go. I looked down and the chain was broken. I mean, what are the odds that the link that makes the bike move would break?"

I then asked them what was wrong with this story. I was trying to make a point about lesion studies, but the same logic applies to many genetic studies as well as other types of studies.

I don't know how pedagogically effective it was, but I liked it. (I also told the class afterword that what was wrong with the story was that I didn't own a bicycle.)

Tarlach said,

December 13, 2009 @ 5:01 pm

If news media are not reporting news factually, that's simply called lying or being wrong. It has nothing to do with launguage itself.