Munroe's Law

« previous post | next post »

Jesse Sheidlower, who as editor-at-large of the Oxford dictionary has a special right to an opinion about such things, emails:

Please, please, someone write about this. I especially love the mouseover text.

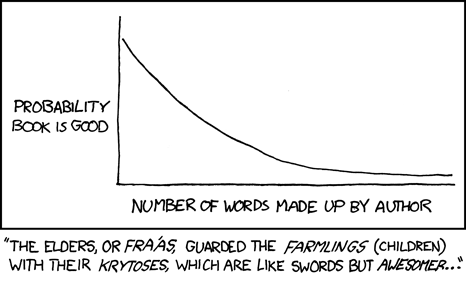

"This" is a recent xkcd strip:

The mouseover text is "Except for anything by Lewis Carroll or Tolkien, you get five made-up words per story. I'm looking at you, Anathem."

Well, I though about posting this when it first appeared on xkcd, but decided that I had nothing to add. But now I can add that Jesse likes it too. And that if you missed Jesse at the Yale University Library event on Oct. 1, there's plenty of time to plan for the event on Nov. 18 at the Philadelphia Free Library, celebrating the 80th Anniversary of the OED.

Oh, I can also add that a search of Google Books suggests that "krytoses" is still available for someone to use as one of their five.

And also, Randall didn't put the "free five" into the graph. Unless he means that after five, the (exponential?) decay in probability of goodness passes below some threshold, not that you get five made-up words before the probability of goodness is affected.

Justin Hilyard said,

October 9, 2008 @ 4:52 pm

I think you misread; he's saying Tolkien and Carroll are the only ones that get a free five. Everyone else doesn't get any free made-up words.

Mark Liberman said,

October 9, 2008 @ 4:57 pm

@Justin: No. Tolkien's books contains hundreds if not thousands of made-up words; Carroll's contain at least dozens; and Randall is clearly giving both of them a pass, for whatever number.

xkcd - A Webcomic - Fiction Rule of Thumb « Charlottesville Words said,

October 9, 2008 @ 5:12 pm

[…] Via Language Log […]

Karen said,

October 9, 2008 @ 5:23 pm

No, it's pretty clear: EXCEPT FOR Tolkien or Carroll, you get five words.

And clearly it's because they're the ones keeping the "probability book is good" line from hitting zero.

Ollock said,

October 9, 2008 @ 5:46 pm

Considering that Tolkien created languages* for his books, yes, I think the intention is that he and Carroll get more than five.

Anyway, it is pretty funny. The graph should descend faster if the reader is given no reliable clues as to pronunciation of the words (so words with completely extraneous apostrophes, strange spelling rules, or just no thinking about pronunciation at all get extra weight). It's a common complaint among hard-core conlangers that many fictional words and languages use odd apostrophes and diacritics that don't seem to do anything, or spellings that are really ambiguous and never explained (though some have other, less reader-friendly priorities in spelling).

*though we'll never know how developed those languages really are, because of his fiddly revisions.

Jason Green said,

October 9, 2008 @ 5:49 pm

I wondered if either or you or Jesse have read Anathem (the latest novel by Neal Stephenson) and whether, particularly as related to it, given the mouseover text, you find the hypothesis to be true.

Micah said,

October 9, 2008 @ 5:49 pm

I think the five free words are noted in the graph; notice the gap between x=0 and the beginning of the curve.

I'd like to see a graph that takes into account whether the author is neologising along standard lines morphologically and phonologically.

Benjamin Zimmer said,

October 9, 2008 @ 6:13 pm

More info on events celebrating the OED's 80th here.

Benjamin Zimmer said,

October 9, 2008 @ 6:30 pm

The rule (with exceptions) vaguely reminds me of Roger Ebert's First Law of Funny Names, as given in the glossary of his Video Companion:

I would add Preston Sturges as a third exception (Ignatz Ratzkiwatzki, Trudy Kockenlocker, John D. Hackensacker…).

SteveDT said,

October 9, 2008 @ 6:42 pm

What you just said. The mouseover text shows that his tolerance for made up words is limited, but even one decreases the probability that the book is good. The threshold of tolerance is approximately where the graph begins to flatten out.

Sundrop said,

October 9, 2008 @ 6:49 pm

What about Shakespeare?

Ray Girvan said,

October 9, 2008 @ 6:50 pm

Regardless of the specific interpretation of the graph, I don't think the rule washes. Counterexamples: the beautiful eggcorn-like neologisms in Hoban's Riddley Walker, or the Russian-derived ones of "nadsat" in A Clockwork Orange.

The badness lies more in how cumbersome and/or etmologically stupid such neologisms can be, particularly when they're used for false exoticism of the Call a Rabit a Smeerp variety. I still remember from years back sitting through a writing group session where someone was reading a ghastly novel involving aliens who drank stuff called "tarril" (made by putting dried leaves into boiling water) and eating with a "sprong" (a little hand-held metal tool with three points on the end).

Karen said,

October 9, 2008 @ 7:09 pm

C'mon: it's the probability decreasing. It's only improbable that a book will be bad, not a given.

Simon Cauchi said,

October 9, 2008 @ 7:10 pm

Let Max Beerbohm be joined with Carroll and Tolkein, on the strength of such coinages as "cupster", "gastrocracy", "immarcescibility", "inenubilable", "nomady" (as noun), "octoradiant", "omnisubjugant", "ovinity", "taurinity", "ventrirotund", "virguncules" — none of which I could find in my 1971 micrographic edition of the OED. He also revived some obsolete or rare words, such as "opetide" and "aseity".

dr pepper said,

October 9, 2008 @ 7:40 pm

I think we should distinguish between new words adapted from the existing vocabulary and those created from scratch.

Blake Stacey said,

October 9, 2008 @ 8:08 pm

I've noticed a fair number of people (in, e.g., this Pharyngula thread) saying that the rule doesn't work and offering their favourite one or two books-with-many-made-up-words as "counterexamples". I think there's a tendency to misread the vertical axis of the graph: instead of "probability book is good", it is parsed as "goodness of book".

Supposing that the goodness of a book is a binary variable — it's either good or bad, nothing in between — then we could estimate the probability of being good as a function of the number of made-up words. Just draw a random sample of books with N words coined by the author, count the number of good ones, and divide. (This is, of course, a manifestly silly thing to do, but a clever statistician can perform six impossible studies before breakfast — and the graph is a joke in a comic strip anyway.) Basically, we'd be treating the production of books as a series of Bernoulli trials, where each book has some probability p(N) of being good. However, once the book is published, it's either good or bad, not "fractionally worth reading".

The instinct appears to be to conflate the worth of a particular book, a binary variable, with the average over a set of books, a value which belongs to no book (well, maybe it's owned by the family with 2.7 children!).

Phutatorius said,

October 9, 2008 @ 8:20 pm

What about A Clockwork Orange? Exception that proves the rule?

bulbul said,

October 9, 2008 @ 8:45 pm

When I first saw this, I immediately thought of "Matter", Iain M. Banks' latest Culture novel, especially the flora and fauna therein. But then again, I am not a native speaker of English, so maybe just like Max Beerbohm, Banks merely resurrected some obsolete words. Anybody else who read "Matter" wanna chip in?

Also, I think people who invented languages or -lects for their fictional worlds should get a pass. Tolkien is an obvious example, so is Burgess and Sapkowski.

mollymooly said,

October 9, 2008 @ 9:07 pm

Second what dr pepper said. Science fiction/fantasy goes for the totally-made-up klthondur with italics; humorous prose goes for the flossomy newfanglisms without italics.

Elliott Mason said,

October 9, 2008 @ 9:26 pm

My favorite take on the 'language is different in this book, but for a good reason' meme is Harry Turtledove's short stories about the australopithecenes-survive universe of his, collected in A Different Flesh; because of the nature of his What-If, there are no 'Native Americans' of a homo-sapiens species; there are instead nonverbal hominids.

So he had to try to not use any word in modern American English that's descended in any way from a Native-American root. He did pretty well, too, though he does gladly tell a tale on himself about at least one he missed … an avid reader came up to him in a high dudgeon at the first convention he attended after the book's publication, indignant that he'd missed that 'woodchuck' is native-derived. Because of this, some authors refer to worldbuilding screwups that result from authorial assumptions as 'woodchucks'.

Forrest said,

October 9, 2008 @ 9:31 pm

A plaxtonical theory. Does it apply in the egratulating sense? A blog comment with two made up words is more likely to be bad than a novel with the same two…

I'm curious just how made-up a word has to be? When Orwell wrote 1984, would thoughtcrime or doublespeak count? Those are concatenations, not entirely new inventions. Unlike some of the complaints above, about bizarre spellings, useless apostrophes, and such, 1984 had a strict taxonomy for its made-up words … and the bizarre ( but compelling ) idea of reducing the number of entries in the dictionary every year. But then I didn't like 1984 on balance; the story itself was good, but, the political diatribe that overwhelmed the second half of the book brought it down a few pegs.

Skullturf Q. Beavispants said,

October 9, 2008 @ 9:50 pm

Making up new words can be a perfectly cromulent thing to do.

Alan Gunn said,

October 9, 2008 @ 10:22 pm

Those pointing out that a few counterexamples don't disprove the thesis are right in principle, but I can't offhand think of bad books with a lot of made-up words. The bad books I have, for one reason or another, finished (Tom Clancy, many nonfiction work-related books) have few made-up words, perhaps none.

antrastan said,

October 9, 2008 @ 10:29 pm

Has xkcd read Celan?

Celan is a genius of the surprising compound.

antrastan said,

October 9, 2008 @ 10:30 pm

No, Beavispants, you mean 'frevolent'.

Paul Donnelly said,

October 9, 2008 @ 11:35 pm

So, this is a cartoon about the probability of books with lots of made-up words being good, and the only books mentioned are both full of made-up words and likely to be rated good by a fair number of people? It's almost as if he just read "Anathem" and was mindlessly following some kind of "nerdy reference + graph = comedy gold" formula. But who am I to argue with success?

John Cowan said,

October 10, 2008 @ 1:59 am

Oddly enough, Tolkien didn't actually coin that many words in and for The Lord of the Rings. It's true there are almost 300 coined names, some from English components, some from Elvish languages. But Tolkien's lower-case words are pretty much English, though he does have a broad vocabulary: carcanet, mathom, northmost, riverward, vanishment, westering, etc.

I made a wordlist of the L.R., which has just over 8000 distinct words (including inflectional forms, HTML artifacts, etc.) I then subtracted words found in a large English wordlist of 81,536 words, leaving 997 candidate words. Removing capitalized words (the source of the name count above after I removed plurals and such), British spellings, inflectional forms, dialect words like axin' 'asking', rare words that are nevertheless found in the OED, and so on, I wound up with only 65 words.

Of these 65, 51 are Elvish or Orkish: all but four of these are used only in quotation marks when a character is speaking in one of those languages. The four are crebain, ithildin, miruvor, and mithril.

The remaining 14 words are: backarappers, dolven, eleventy-one, elven (which has now become part of standard English), errandless, gentlehobbit, haywards ('hedge-guards'), hobbit, rightabouts, smials, starmoon (translation of ithildin above), truesilver (translation of mithril above), tweens, and warg. Not much for half a million words of text!

Ray Girvan said,

October 10, 2008 @ 4:17 am

> I think there's a tendency to misread the vertical axis of the graph: instead of "probability book is good", it is parsed as "goodness of book".

Point taken.

Re examples, a peculiar one is Jack Vance's The Dying Earth, which uses uncommon pre-existing words, but with invented meanings. For instance, a "deodand" is a carnivorous humanoid, and an "oast" a riding beast.

Nick Lamb said,

October 10, 2008 @ 5:33 am

Stanisław Lem is an excellent writer who used lots of nonsense words (which his translators had to translate appropriately, which can't be an easy task) when he felt they were appropriate, e.g. in The Cyberiad when Trurl's machine for making everything that begins with n is asked to make "nothing" it destroys among many other things brashtions, plusters, and laries. It later refuses to recreate them, arguing that since they don't begin with N it doesn't know how. This is a particularly inspired use of made up words, since of course the story also acts as a "Just so" for why these words don't mean anything.

I wondered for moment (since we've already had examples from Banks) whether Science Fiction as a whole gets a pass. But I think it's actually simpler than that – the problem isn't words that are made up, since actually no-one knows all the words in the dictionary, and it hardly matters whether a book of fiction uses a freshly minted word or a terribly old one, you aren't going to bring up the OED to check. The problem is words that don't fit. Clumsy language in other words, a downfall of any writer regardless of genre.

Chris Clark said,

October 10, 2008 @ 5:53 am

I think, specifically, the problem exists when writers don't integrate their coined words and existing words together sucessfully – they just dump a fake word in an otherwise normal (and often bland) sentence purely so that the reader gets that they are not in Kansas anymore (ie 'Starkiller ordered a jambalaburger with fries and a cola'). So bad science fiction can, with simple judicious word substitution, be turned from scifi to western to fantasy. This Penny Arcade comic covers the phenomenon. And, of course, since the probability of a book being good is pretty low to begin with, having made-up words in it just gives the majority of bad writers one more thing to suck at. It's not how I'd draw the graph, though. For one thing, I think there should be a Herbert's Peak, where the number of made-up words becomes so great that a glossary is required.

greg said,

October 10, 2008 @ 9:07 am

I'm reading Anathem at this very moment, and while it does take a bit of getting used to the odd vocabulary, a lot of them seem to have a pseudo-etymological basis, or are just words that he has changed the meaning of.

The male members of the 'mathic' orders who live cloistered away from the surrounding world are 'fraas' which could easily be an alteration of 'friars' or 'fathers'. Female members are 'suurs' which would have come from 'sisters'. The title for especially venerated members of the mathic orders is 'Saunt'. The book's narrator gives the possible etymology as being from 'savant', though there is an obvious possible connection to 'saint'. Stephenson does include a glossary though. The title of the book itself is a combination of the words anthem and anathema. When a person is banned from the mathic orders, a ceremony is carried out in which a song is sung which declares the person to be no longer welcome. An anthem declaring them anathema.

In a lot of ways, it reminds me of A Canticle for Liebowitz.

With regard to the graph, I'd say that Randall did include that 'free five' in his graph. The curve doesn't intersect with the y-axis, indicating an off-set of some "number of words made up by the author". Since we have no scale, it is safe to assume (if the gap was intentional) that the gap there is the 5 free words that all authors get before their book is affected by the probability function.

Trent said,

October 10, 2008 @ 10:16 am

Possibly many are taking a funny cartoon (and mouseover) a bit too seriously? How can arguments on this issue be anything but circular? — Neologisms harm fiction except when they don't.

Mihai Pomarlan said,

October 10, 2008 @ 10:52 am

Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn! Ia! Ia! Ia!

Mihai Pomarlan said,

October 10, 2008 @ 11:22 am

On a more serious note, a quote from Simon Singh's "The Code Book", about deciphering ancient texts:

"An informal test for the accuracy of a decipherment is the number

of gods in the text."

Conrad Roth said,

October 10, 2008 @ 12:47 pm

Wow, I guess Finnegans Wake must be the worst book ever. Or at least the book most likely to be bad.

Claire Bowern said,

October 10, 2008 @ 1:01 pm

"An informal test for the accuracy of a decipherment is the number

of gods in the text."

The archaeological corollary of this is the number of "ritual objects" found at a site.

Blake Stacey said,

October 10, 2008 @ 1:23 pm

Jorge Luis Borges, "Joyce's Latest Novel" (1939). Originally published in El Hogar magazine; translated by Eliot Weinberger and reprinted on p. 195 of Selected Non-Fictions (1999).

Ollock said,

October 10, 2008 @ 1:42 pm

Of course we're taking it too seriously, but then again, it's an interesting discussion.

Also, people are bringing up some different forms of neologisms that appear in fiction: there are words that can be formed in English through normal derivation (ex goodspeak), words from an arbitrary "alien" language (ex mellon — the Elvish [Quenya, I believe] word for "friend") and various routes in between. (Actually, I'm not sure if Tolkien's languages really go all the way out to an extreme, since they're drawn from real languages he was familiar with and serve as mythological ancestors to modern languages).

So are some types of coinages more tolerable than others? For me, archaisms and derived coinages with somewhat-decipherable meanings work better. If you use a completely novel or arbitrary term, it needs to be clarified in context what that word means — so overuse of such terms can clutter the text with too many explanations of terminology and not enough action.

Faldone said,

October 10, 2008 @ 1:44 pm

The number of "ritual objects" found at a site is inversely proportional to our level of understanding of the culture.

Simon Cauchi said,

October 10, 2008 @ 4:17 pm

Apropos of Finnegan's Wake. I've always enjoyed Evelyn Waugh's comment on James Joyce: "Experiment? God forbid! Look at the results of experiment in the case of a writer like Joyce. He started off writing very well, then you can watch him going mad with vanity. He ends up a lunatic." (See The Paris Review, 30, Summer Fall 1963, p. 80.)

Jamie Hopkings said,

October 10, 2008 @ 7:20 pm

On the made-up-name-are-not-funny thread, I'm surprised no one has mentioned Douglas Adams as a worthy exception.

What kind of person could encounter the names Slartibartfast and Vroomfondel with a straight face?

Nathan Myers said,

October 10, 2008 @ 7:36 pm

Let us here complain about Gene Wolfe and his "Urth of the New Sun", with its alien babblers called "cacogens". I presume Wolfe is riffing off the latinate "cacophony", but as I read it proto-indo-european-wise, it means "shit-makers".

Ralph Hickok said,

October 10, 2008 @ 8:16 pm

greg said,

"The male members of the 'mathic' orders who live cloistered away from the surrounding world are 'fraas' which could easily be an alteration of 'friars' or 'fathers'."

"Fra" is a shortening of the Italian frate, for brother, and it was once widely used as a form of address for a monk or friar. There was a rather famous artist-monk, Fra Filippo Lippi, who become Lippo Lippi in Browning's dramatic monologue. More recently, Fra Lippo Lippi is the name of a Norwegian pop band.

Jeff Prucher said,

October 10, 2008 @ 8:50 pm

@Nathan Myers: the thing about Wolfe's New Sun books is that he actually went out of his way to avoid making up words. Cacogen is a real English word, meaning "an antisocial person", although he seems to have gotten it mixed up with cacogenesis, "morbid or depraved formation", because he glosses it as "those filty born".

Kevin Iga said,

October 10, 2008 @ 10:26 pm

greg said,

"The male members of the 'mathic' orders who live cloistered away from the surrounding world are 'fraas' which could easily be an alteration of 'friars' or 'fathers'. Female members are 'suurs' which would have come from 'sisters'. The title for especially venerated members of the mathic orders is 'Saunt'. The book's narrator gives the possible etymology as being from 'savant', though there is an obvious possible connection to 'saint'."

In contrast to Ralph Hickok's suggestion, might French be a better fit for the source of these terms than Italian? Then "fraas" comes from "frères" (brothers), "suurs" comes from "soeurs" [sörs] (sisters), and "saunt" comes from "saint".

Not that the author is necessarily taking a single language as an inspiration for these words.

GAC said,

October 11, 2008 @ 12:49 am

@Jamie

Of course! Plus, he gets away with ridiculous technobabble and pseudoscience, as well as copious deus ex machina. (Of course, it's all in the name of making fun of those devices.)

@Kevin and Greg

Spanish also has similar monk/nun titles. A common title for friars (and monks?) is fray, and for a nun it is sor (note, this are different from the common terms for siblings: hermano/hermana).

David Marjanović said,

October 11, 2008 @ 3:08 pm

Those who cannot spell iä shall be eaten next to last.

Randy said,

October 12, 2008 @ 12:49 am

Is there anyone else besides me who thought the phrase "Probability book is good" meant that the xkcd author was commenting on the quality of probability books, taking "probability book" to be the subject of the sentence?

I'm not aware that it is more probable for a probabilist to make up a words than it is for any other brand of academic. However, the word krytoses is strongly reminiscent of a measure on a probability distribution known as kurtosis [1]. Kurtosis measures the sharpness of the peak of a probability distribution, and swords are sharp (well, the good ones are). Without stopping to analyze the quality of my hasty interpretation, I further assumed that some applied statistician, working with an anthropologist perhaps, made up the words fra'as and farmlings to describe the respective subpopulations.

[1] I seem to recall, though I cannot find evidence at the moment, that some authors of this blog would like it if a larger proportion of the population understood that second most basic of useful statistical measures known as the standard deviation. If you have taken up this challenge, the next most basic, though perhaps not as useful, is the skewness, followed by the kurtosis.

James Wimberley said,

October 12, 2008 @ 5:25 pm

Was Lewis Carroll in the habit of inventing words? The Jabberwocky poem is stuffed with them of course, but I can't offhand think of another example. In fact neologisms would work against his logical and linguistic jokes.

Mihai Pomarlan said,

October 12, 2008 @ 6:35 pm

@James Wimberley:

The word "portmanteau" from 'Alice through the looking glass', although that's the book that also includes Jabberwocky.

Then there's 'The Hunting of the Snark', but I'll have to read it again to see if there are any new words in there (as opposed to Jabberwocky re-uses).

Jabberwocky is much more famous than Snark though, and several words associated with it have been happily included in the English language since (vorpal, chortle, galumphing and of course portmanteau). I can't think of such an example of a word from Snark that made it to the mainstream.

Freddy said,

October 12, 2008 @ 9:57 pm

I think he should have included Dr. Seuss too. :)

DRK said,

October 13, 2008 @ 6:43 pm

Well, the snark was a Boojum, you know.

Trent said,

October 14, 2008 @ 8:17 am

Mihai said,

"Then there's 'The Hunting of the Snark', but I'll have to read it again to see if there are any new words in there (as opposed to Jabberwocky re-uses).

Jabberwocky is much more famous than Snark though, and several words associated with it have been happily included in the English language since (vorpal, chortle, galumphing and of course portmanteau). I can't think of such an example of a word from Snark that made it to the mainstream."

Though I suspect humor on Mihai's part, I'll go ahead and point out that "Snark" made it into the mainstream.

Mihai Pomarlan said,

October 14, 2008 @ 2:04 pm

@Trent:

You are too kind, I was actually being earnest and under the assumption (oh, those mental landmines) that snark(y) & co. have nothing to do with the Snark.

So I went online to try to find the history of this family of words, and finally arrived upon this

http://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2007/01/hunting-origin-of-snarky.html

where it is mentioned that the earliest use of the verb snark recorded in the OED is from 1866, ten years before the Hunting of the Snark was published. In 1866, it meant "to snore". By 1882, according to what that blog says that the OED says, another meaning, "to nag"/"to find fault", was added.

Obvious next step- I went to http://www.oed.com to check for myself but *gasp* it requires a subscription! Alas, my investigation ends here, but if anyone can access that treasure trove of history that is the OED, and is interested in checking, can do so.

Happy snarky hunting!

Stieg Hedlund said,

October 14, 2008 @ 6:38 pm

I forget which Sci-Fi writer came up with the idea of "Shmeerps", biut there's a good discussion of that idea and good neologisms here: http://www.reflectionsedge.com/archives/feb2005/mnwsl_es.html

Anonymous Cowherd said,

October 17, 2008 @ 2:05 pm

@Mihai: "The word "portmanteau" from 'Alice through the looking glass'… of course portmanteau"

"Portmanteau" was a perfectly cromulent word before Carroll got hold of it; it means a kind of suitcase in which one might carry (porte) a coat (manteau) in addition to other personal items. Hence Carroll's use of it to mean a word into which are packed several other words with their attendant meanings. IIRC, he explains it at one point (in "Alice", I think?) in terms that imply that his target audience was familiar with the suitcase kind of portmanteau already.

Sili said,

October 19, 2008 @ 8:01 am

The mention of statistics reminded me that scientists are constantly making words up (and don't get me started on commercial drugnames).

It's probably good that there are no numbers on the ordinate since it's a wellknown fact that "95% of everything is crap". So the probability cannot begin all that high on the axis.

Blake Stacey's observation on "goodness of book" is reminiscent of the problem with the public understand of statistical means as "Platonic ideals".

Jens Fiederer said,

October 22, 2008 @ 1:04 pm

While the excellent cartoonist is not the only one to lament the synthetic vocabulary of Anathem (the first review I read judged the book excellent, but hard to get into for that very reason), I actually enjoyed it.

Generally the words he coins are derivatives of ones you already know, except for names of people.

He does an excellent job leading you down the garden path with his explanations – for example, you start thinking "Diaxx's Rake" might be his version of "Occam's Razor" – but it is not, it is the principle (I am not aware of the standard name, if is has one) that something is now true just because you think it should be.

THEN, when you are off your guard, he pulls out his version of Occam's Razor, in this world known as "Saunt Gardan's Steelyard".

("Saunt", itself, is the atheist version of "Saint" derived from "Savant" (U and V of course being indistinguishable carved in stone)).

Definitely makes my list of the top 100 books ever.

GAC said,

October 22, 2008 @ 4:47 pm

("Saunt", itself, is the atheist version of "Saint" derived from "Savant" (U and V of course being indistinguishable carved in stone)).

Is that the actual explanation given? I would think it could be derived from maybe two hypothetical future sound change rules.

[səvɑnt] > [svɑnt] (schwa deletion) > [sɑnt] (cluster simplification) (with "saunt" being the clearest orthographic representation for English speakers)

At least, in the real world that would seem more plausible, since the letterforms of U and V have been distinct for a good long time (even in stone, unless you're writing Latin) and people don't acquire language from writing. But maybe in Anathem something has happened to the old fashioned way of communication through speech? (I guess I have to go read it now.)

Jens Fiederer said,

October 24, 2008 @ 12:30 am

Actual explanation given:

Saunt: (1) In New Orth, a term of veneration applied to great thinkers, almost always posthumously. Note: this word was accepted only in the Millennial Orth Convox of A.R. 3000. Prior to then it was considered a misspelling of Savant. In stone, where only upper-case letters are used, this is rendered SAVANT (or ST. if the stonecarver is running out of space). During the decline of standards in the decades that followed the Third Sack, a confusion between the letters U and V grew commonplace (the "lazy stonecarver problem"), and many began to mistake the word for SAUANT. This soon degenerated to saunt (now accepted) and even sant (still deprecated). In written form, St. may be used as an abbreviation for any of these. Within some traditional orders it is still pronounced "Savant" and obviously the same is probably true among Millenarians.

Xenobiologista said,

November 16, 2008 @ 1:31 am

The TVTropes wiki has an entire article about the phenomenon of authors/screenwriters needlessly relabelling things, by the way: Call A Rabbit A Smeerp