Linguistic Diversity and Traffic Accidents

« previous post | next post »

An important new paper (Sean Roberts & James Winters, "Linguistic Diversity and Traffic Accidents: Lessons from Statistical Studies of Cultural Traits", PLOS ONE 2013, is explained clearly in a blog post by one of the authors, "Uncovering spurious correlations between language and culture", a replicated typo 8/15/2013:

James and I have a new paper out in PLOS ONE where we demonstrate a whole host of unexpected correlations between cultural features. These include acacia trees and linguistic tone, morphology and siestas, and traffic accidents and linguistic diversity.

We hope it will be a touchstone for discussing the problems with analysing cross-cultural statistics, and a warning not to take all correlations at face value. It’s becoming increasingly important to understand these issues, both for researchers as more data becomes available, and for the general public as they read more about these kinds of study in the media (e.g. recent coverage in National Geographic, the BBC and TED).

One of my favorite bits is the following (and not only, or even mainly, because they link to one of my posts!):

Everyone knows that correlation does not imply causation, but there are other problems inherent in studies of cultural features. One problem that is often discounted in these kinds of study is the historical relationship between cultures. Cultural features tend to diffuse in bundles, inflating the apparent links between causally unrelated features. This means that it’s not a good idea to count cultures or languages as independent from each other. […]

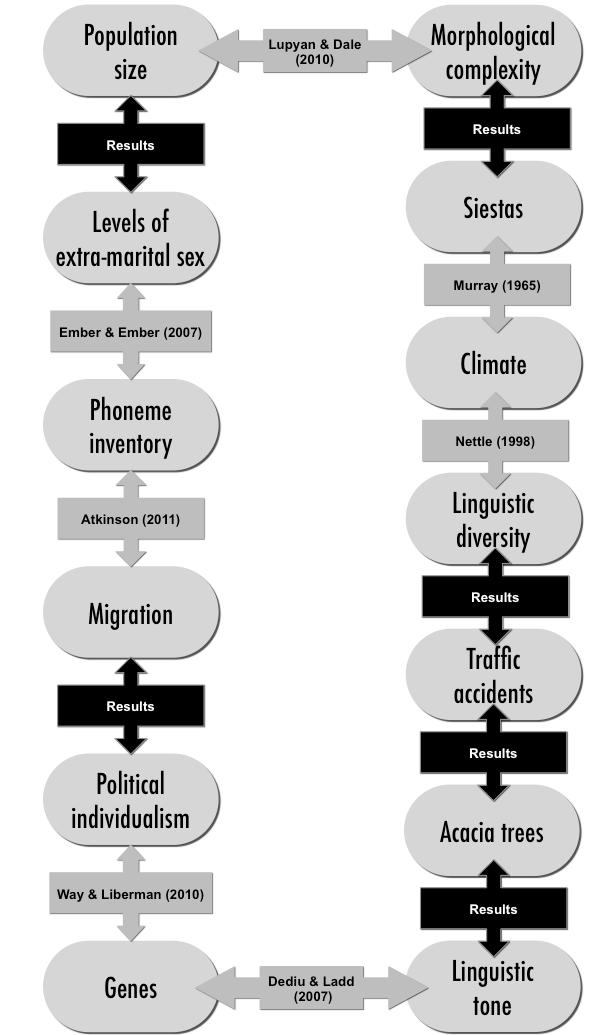

Our paper tries to demonstrate the importance of controlling for this problem by pointing out a chain of statistically significant links, some of which are unlikely to be causal. The diagram below shows the links, those marked with ‘Results’ are links that we’ve discovered and demonstrate in the paper.

For instance, linguistic diversity is correlated with the number of traffic accidents in a country, even controlling for population size, population density, GDP and latitude. While there may be hidden causes, such as state cohesion, it would be a mistake to take this as evidence that linguistic diversity caused traffic accidents.

Read the whole blog post (and also the paper), if you're interested in things of this sort.

Charles in Vancouver said,

August 15, 2013 @ 3:18 pm

The idea that cultural features diffuse in bundles is a really nicely stated concept.

I wonder about that traffic accident correlation. Perhaps driving is more predictable and hence less accident prone in locales where most people share the same attitudes towards driving. And those attitudes could be grouped culturally such that more linguistic diversity would mean less predictable driving.

Rubrick said,

August 15, 2013 @ 3:40 pm

it would be a mistake to take this as evidence that linguistic diversity caused traffic accidents.

Clearly the causality is the other way around. People produce all kinds of novel utterances when they wreck their cars.

tk said,

August 15, 2013 @ 4:29 pm

I am a cultural anthropologist/ethnohistorian, so I have to ask:

What's a bundle?

Ever since Leslie Spier and Clark Wissler tried to map the diffusion of the Sun Dance, we've been trying to define them, and I 'm glad someone has finally done it. ;-)

[(myl) We start from the observation that since features diffuse (to a significant degree) via geographical proximity — or in any case via some communications network that is far from fully connected — it follows that the result of even random diffusion is to create highly (statistically) significant correlations of feature values. This is a (loosely stated) theorem, not an empirical observation.

In addition there are cases where it seems plausible that things tend to diffuse together — if you borrow rice, you're likely to borrow cultivation and harvesting tools, cookware, recipes, etc. But this is an empirical claim, and whether the plausibility can be proved statistically is another matter.]

Bloix said,

August 15, 2013 @ 7:47 pm

All right, I'm feeling my annoying pedant coming on:

"Everyone knows that correlation does not imply causation"

Actually, correlation does imply causation. It does not prove causation, but it implies it rather strongly.

The odds that A causes B are much higher if A and B are correlated than if they're not. Which is what is meant by "implies."

Yet you see people saying "Correlation does not imply causation!" as if it means that correlation disproves causation.

If a study shows statistically significant correlation between A and B, there is likely to be some sort of causation somewhere. Either A is a cause of B, or B is a cause of A, or an as yet unidentified C is a cause of both A and B. Or perhaps C is a cause of A, and D is a cause of B and C. Etc. Or perhaps there's something wrong with the study.

Ray Dillinger said,

August 15, 2013 @ 8:10 pm

'Implication' in the jargon of mathematicians and scientists means something very different from the fuzzy concept which 'implication' in English does not fulfil.

'Implication' in that particular dialect means that the implied item simply cannot exist in the absence of the implying item. Thus an utterance such as

"Correlation does not imply causation" is correct in that jargon where 'implication' has its mathematical meaning, while

* "Correlation does not imply causation" is incorrect in more standard English where the word 'implication' has its usual loading.

Ray Dillinger said,

August 15, 2013 @ 8:13 pm

Hmm, I misstated that.

Apologies.

'Implication' in mathematical jargon would mean that correlation cannot exist without causation, not the other way round as I stated above.

I think that this is an example of misnegation on my part.

Douglas Bagnall said,

August 15, 2013 @ 8:56 pm

Rubrick said

Clearly the causality is the other way around. People produce all kinds of novel utterances when they wreck their cars.

Unfortununately, if you read the paper, they actually compare “road fatalities”, not “traffic accidents” as claimed in the title. That might have a productive linguistic effect.

Ted McClure said,

August 15, 2013 @ 9:06 pm

I confess that as I read down the relation loop above, I was hoping that it would prove inconsistent somewhere, some sort of Condorcet problem – going clockwise gives one result, counterclockwise the opposite. Oh, well.

Ben Artin said,

August 16, 2013 @ 3:09 am

Also see Why Most Published Research Findings Are False

Bill Benzon said,

August 16, 2013 @ 3:55 am

Sounds like a version of Galton's Problem:

Sidney Wood said,

August 16, 2013 @ 4:56 am

So where does this leave us with altitude and ejectives?

tk said,

August 16, 2013 @ 6:06 am

"[(myl) We start from the observation that since features diffuse (to a significant degree) via geographical proximity — "

Ah, the Age-Area Hypothesis, or the Kulturekries, or both, or something else completely new and different.

Bloix said,

August 16, 2013 @ 9:41 am

Ray Dillinger:

Okay, so you're saying that A => B, read as "A implies B", means "if A then B."

And if A does not imply B, then if A then not-B.

[(myl) No, "X does not imply Y" in this context means

NOT(X ⊃ Y)

not

(X ⊃ NOT Y)

]

But that's not how the quoted article uses it. They say:

"Everyone knows that correlation does not imply causation."

How would you represent that? Make correlation A and Causation B, and you have: A =/=> B. Or, if A then not-B. That's not what they mean.

What they mean to say is something like, correlation does not necessarily imply causation.

[(myl) No, what they mean to say is "It is not the case that if two things are correlated then a casual relationship exists between them".]

Eric P Smith said,

August 16, 2013 @ 9:51 am

@Bloix: or, in the jargon I was taught at University, correlation does not validly infer causation.

Which is a horrible use of 'infer'.

chh said,

August 16, 2013 @ 10:19 am

Bloix,

Look at Ray Dillinger's correction if you haven't already. The technical sense of 'imply' means what you're trying to make it mean.

(A -> B) doesn't mean (-A -> -B). It does mean (-B -> -A), like Ray noted in his correction.

-(A -> B) (like in the statement 'correlation does not imply causation) means that it's not the case that knowing that A is true allows you to conclude that B is true. That's the intuition you've been expressing, and it's consistent with the technical sense of 'imply' for logical entailment.

Correlation and causality | swphonetics said,

August 16, 2013 @ 6:24 pm

[…] This is how Seán Roberts and James Winters introduce their recent article: Linguistic diversity and traffic accidents: lessons from statistical studies of cultural traits (PLOS ONE, 2013, accessed August 2013), reviewed and discussed in Language Log. […]

Ray Dillinger said,

August 17, 2013 @ 4:13 am

Causation, correlation, implication.

"Correlation does not imply causation" is a phrase from mathematics/logic that actually has broader parlance than the sense of 'imply' that it uses. People are expected to know the saying; but depending on what they think 'imply' means they may not be able to parse it correctly.

Suppose we did a study and found that knowing the saying was strongly correlated with being able to correctly parse it. This is plausible since the saying comes from math & logic and the sense of 'imply' used is common in the same intellectual subgroup.

According to the saying itself, that would not imply that knowing the saying *caused* the ability to parse it.

The issue is that the ability to parse it correctly (knowledge of the word's jargon meaning) is not in fact caused by merely knowing the saying, because it cannot be picked up from context without a prior understanding of what the saying means.

IOW, knowledge of the saying can exist without knowledge of the word's precise meaning, even though knowledge of the two things are strongly correlated.

I managed to Murdoch this when I tried to explain it first; I posted a correction within 3 minutes according to the above, but the original article is still there.

Correlation and causality: ejectives | swphonetics said,

August 29, 2013 @ 5:09 am

[…] This is how Seán Roberts and James Winters introduce their recent article: Linguistic diversity and traffic accidents: lessons from statistical studies of cultural traits (PLOS ONE, 2013, accessed August 2013), reviewed and discussed in Language Log. […]

"Create", "Creative", "Creativity" | Poetry & Contingency said,

September 4, 2013 @ 9:17 am

[…] as well as a rise in the use of the word "create" to describe this. It may well be, unlike almost every use of Ngrams you hear about in the popular media, tracking a cultural as well as a linguistic […]