Prestigious nonsense, tendentious frames

« previous post | next post »

Kimmo Ericksson, "The nonsense math effect", Judgment and Decision Making 7(6) 2012:

Kimmo Ericksson, "The nonsense math effect", Judgment and Decision Making 7(6) 2012:

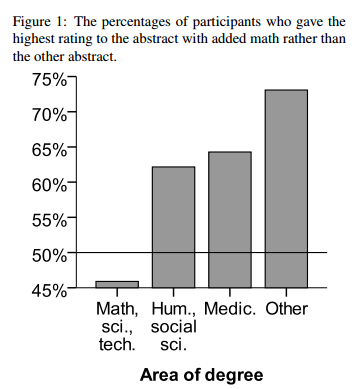

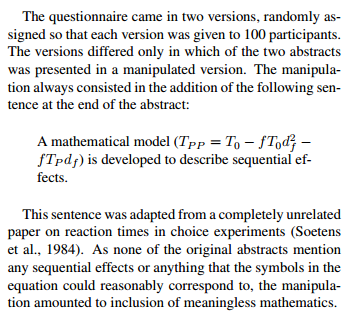

In those disciplines where most researchers do not master mathematics, the use of mathematics may be held in too much awe. To demonstrate this I conducted an online experiment with 200 participants, all of which had experience of reading research reports and a postgraduate degree (in any subject). Participants were presented with the abstracts from two published papers (one in evolutionary anthropology and one in sociology). Based on these abstracts, participants were asked to judge the quality of the research. Either one or the other of the two abstracts was manipulated through the inclusion of an extra sentence taken from a completely unrelated paper and presenting an equation that made no sense in the context. The abstract that included the meaningless mathematics tended to be judged of higher quality.

Here's a bit more detail about the irrelevant equation:

This reminds me of what Yeats wrote in 1930 to his son's (imaginary) schoolmaster:

Teach him mathematics as thoroughly as his capacity permits. I know that Bertrand Russell must, seeing that he is such a featherhead, be wrong about everything, but as I have no mathematics I cannot prove it.

Yeats was over-optimistic about the power of mathematics to prove Russell wrong, I think, but he was right to see that unilateral conceptual disarmament is a bad move.

A similar effect exists in other cases where prestigious nonsense impresses those who don't understand it very well — Eriksson's bibliography includes Deena Weisberg et al., "The seductive allure of neuroscience explanations", Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience (20) 2008, discussed in "Blinded by neuroscience", 6/28/2005, and "Distracted by the brain", 6/5/2007.

By the time such dimly-understood techno-stuff makes it into the popular press, the effect is often systematic misinterpretation rather than mere awe — especially when publicists (or researchers themselves) encourage it. Daniel McKaughan and Kevin Elliott put an oddly positive spin on such effects in "Voles, Vasopressin, and the Ethics of Framing", Science 7 December 2012:

Recent discussions about the biological determinants of behavior in voles provide an opportunity to reflect on how scientists can frame information in ways that are both illuminating and responsible.

By modulating the density and distribution of vasopressin receptors in specific regions of the brain, scientists can get ordinarily “promiscuous” montane voles to behave more like “monogamous” prairie voles. By the time this research was reported in the popular media, it had become a story about the discovery of a “gene for” “monogamy,” “fidelity,” “promiscuity,” or “divorce” in humans.

Consider the major frames we identified in the media coverage of this research: (i) “genetic determinism,” the idea that a single gene controls even complex social behaviors such as sexual monogamy; (ii) “triumph for reductionism,” the suggestion that soon we will understand love in terms that refer exclusively to physics and chemistry; (iii) “humans are like voles,” a parallel allowing wide-ranging extrapolation; (iv) “happiness drug,” the idea that applying lessons learned from this research to biotechnology efforts could save a relationship or marriage; and (v) “dangers of social manipulation,” which has led to stories about trust sprays of potential use to the military, department stores, politicians, and stalkers.

These frames, albeit crude and oversimplified, can help members of the public understand how research relates to broader social trends, issues, and debates. By paying close attention to the dominant frames used in highly publicized cases like this one, scientists can take advantage of these strengths while preemptively highlighting their potential weaknesses. For example, to correct a common source of misunderstanding in the “humans are like voles” frame, experts could emphasize that ordinary usage of terms such as “monogamy” can differ substantially from their technical applications in biology. (Spending 56% of the time with one's spouse, 19% of the time alone, and 25% of the time copulating with strangers would not qualify as monogamous by ordinary human standards.)

For some further details on neurotransmitters and pair-bonding in voles and men, see "'Cause after all, he's just a vasopressin receptor", 9/5/2008. And combining the rhetorical force of neurotransmitters and mathematical formulae, we present "The Agatha Christie Code: Stylometrics, serotonin, and the oscillation overthruster", 12/25/2005.

John Lawler said,

December 30, 2012 @ 10:10 am

Ericksson's experiment sounds like a scientific validation of Zwicky's Law for higher-level text constituents.

bks said,

December 30, 2012 @ 10:48 am

Bertrand Russell did not disagree with Yeats:

This suggests a word of advice to such of my hearers as may happen to be professors. I am allowed to use plain English because everybody knows that I could use mathematical logic if I chose. Take the statement: “Some people marry their deceased wives’ sisters”. I can express this in language which only becomes intelligible after years of study, and this gives me freedom. I suggest to young professors that their first work should be written in a jargon only to be understood by the erudite few. With that behind them, they can ever after say what they have to say in a language “understanded of the people”. In these days, when our very lives are at the mercy of the professors, I cannot but think that they would deserve our gratitude if they adopted my advice.

–bks

D.O. said,

December 30, 2012 @ 1:38 pm

I guess correct reaction to the request to evaluate paper (or abstract) in an unfamiliar branch of science is to refuse. Assuming that Mr. Ericksson didn't give this option to the participants, the rest is immaterial.

[(myl) But refusing to evaluate is not an option for science writers or for the media in general. Nor is it an option, in the end, for politicians and for the public.

And familiarity — at least at the level of a college course — is not enough to avoid the problem, as the Weisberg et al. paper illustrates.]

D.O. said,

December 30, 2012 @ 2:27 pm

But the solution to this problem is known and quite simple. You ask independent (from authors and controversy if it exists) experts. If properly instituted it might be a part of public service for academics. Wouldn't it be nice if you (Prof. Liberman) get an occasional call from The New York Times with the question like "We are writing up on some exciting new linguistic breakthrough, can you check that we are getting it right?"

[(myl) Most science writers do call around for comments — I get such calls and emails all the time. But this doesn't seem to be enough to fix the (various) problems. I don't think it's easy to provide a systematic solution, but my own suggestion is here.]

Keith M Ellis said,

December 30, 2012 @ 2:44 pm

You post on this theme relatively often. I'm glad that you do because I share your very palpable frustration — and it doesn't seem that there's as many other bloggers writing about this as there ought to be. Obviously, the non-science blogosphere is going to be at least as bad about this stuff as the popular media's reporting on science; and, in fact, it is. Blogging about some bit of research based upon already-misleading popular science reporting, and getting it even more wrong, is part of the blogger's toolkit, an indispensable means for filling out one's expected number of posts for the day.

This particular story is a good example — not so much that the blogging about it has been that bad, but that it's been widely blogged. It's attractive for many of the reasons that are implicit in Elliot's framing examples: they're all opportunities to use the reporting on the research as a means to advance some ideology. In this case, it's attractive to those who are partisans in the soft vs hard science wars, or those who are politically suspicious of the social sciences.

But one part of my daily reading is a moderate number of posts on blogs hosted over at ScienceBlogs. And there's much less blogging about the sorry state of science journalism than I expect. There is some — there's probably a few bloggers who write about this stuff about as often as you. But in my opinion it's a sufficiently dire problem that scientists blogging about science to an audience that is largely composed of non-scientists should be actively combating the problem, and most are not. Granted, ScienceBlogs has at some point in the last few years, been acquired by Scientific American, so, well…

Put aside the argument, which many of us assert, that the general public ought to be more scientifically literate for the sake of the value of scientific literacy. There's a narrower, but even more vital, issue in that various bits of research and various trends in various scientific disciplines all exist in some sort of synergistic relationship with the larger culture, and specifically act as markers and motivations for various political arguments in civil society. As such, it really does matter that the science is correctly represented and not misunderstood.

Andy Averill said,

December 30, 2012 @ 3:57 pm

@DO, the participants were told they'd be paid 50 cents for about five minutes' work (online). That's not even minimum wage. Should we be surprised if they didn't take the experiment too seriously? Or that only the people whose degree is in a mathematically rigorous field weren't fooled?

D.O. said,

December 30, 2012 @ 4:47 pm

@Andy Averill. My problem is that I am not taking this whole paper seriously. With only information given by Prof. Liberman it seems like another "let's prove a stereotype by sloppy research" paper, the type usually criticized on this blog.

[(myl) I took the paper's message to be a limited one: Sometimes irrelevant mathematics can impress readers who don't understand it. It certainly didn't show that irrelevant mathematics ALWAYS has this effect; or even that this specific sort of effect plays a consequential role in the public uptake of science.]

the other Mark P said,

December 30, 2012 @ 5:21 pm

D.O. said,

But the solution to this problem is known and quite simple. You ask independent (from authors and controversy if it exists) experts.

If the problem is real, and I accept that this study is hardly "proof", then this is not the solution.

The problem is not that people are impressed with ridiculous mathematics. That was used in this case to show that merely adding mathematics – any mathematics – impresses people.

The problem is that mathematics impresses people, and so they add in places that really don't need it. There are disciplines today that are riddled with pointless abstraction to mathematics, mostly in a desperate attempt to become a "hard" science rather than a soft humanities subject.

Expert reviewers don't help. They came through the same system and are unlikely to see that removing the mathematics will improve it. Yes, they might find egregious errors, but they won't attack the actual problem – the desire to stick equations into papers where there is no need.

In fact the problem goes a bit deeper. The impressiveness of the mathematics "improves" as it become harder (doh!). So people in some disciplines are forever pushing the boundaries in order to show how very clever they are. In the process they have a tendency to make serious errors – since they aren't actually mathematicians.

I can't imagine giving that sort of paper to a mathematician would help. They would look at it and say "this isn't a reasonable application for the use of this mathematics, regardless of whether the maths is internally correct". And what journal of psychiatry or sociology is going to want to hear that?

thomas said,

December 30, 2012 @ 5:28 pm

@DO. Some places do have an organized service (eg the Science Media Centres in UK, Australia, New Zealand) that solicits expert commentary on press releases or embargoed papers likely to be of media interest. The limitation here is that there's an almost unlimited supply of research-like material out there, so that commenting in advance needs to be very selective.

Many academics are also happy to get requests from journalists, and my department has made a contact list of statisticians by area of application. This also does some good, but again there is time pressure, since a lot of this stuff is 'filler' rather than high priority news, and part of the point is to be able to rework articles from, say, Medical Daily, without taking too much time.

Richard said,

December 30, 2012 @ 5:32 pm

This reminds me a bit of the infamous Sokol/Social Text affair, but done as a real experiment rather than as polemical stunt. I wouldn't be surprised to see the results replicated with the inclusion of an irrelevant graph instead of a formula or, in the case of my field (musicology), a transcription that fails to conform to the theory advanced by the paper.

bks said,

December 30, 2012 @ 8:25 pm

The specific example above hypnotized the subjects with the most protean and magical word in all of Science: model.

–bks

Al Rodbell said,

December 30, 2012 @ 8:33 pm

If the subject is, "How use of mathematics beyond the ability of the audience to understand can be a license for absurdity", this segment of an essay I wrote a few a few years ago should be apt:

I was drawn to this area by watching the four part Nova series Cosmos, The Fabric of the Universe. As someone who never even took a college physics course, I'm in no position to evaluate most of the propositions presented on the program, but there were two that I do feel able to challenge. The first is that time, that intuitive sense that Emanual Kant described as needing no explanation because it was "a priori", meaning part of what makes us human. This is so true that in the very discussion of time even those who refute its reality must use this intuitive understanding. We can't speak of beginnings, ending, of of expansion of the universe with out implicit reference to time.

The reality of time becomes more poignant, more real, as one approaches the end of their life, or in my case when the specter of dementia looms larger, nearer, meaning less time to achieve or to experience before the end of time….for me. There is a neurology researcher whom I have been corresponding with, James Brewer M.D. Ph.D, who has developed a technology to predict within very narrow limits using advanced MRIs how long someone has before dementia will deprive them of their cognitive abilities. It is all about time, devastating when it turns out to be short, exhilarating when his tests show it to be more than the patient anticipated.

Brewer is an empathetic man, but like the theoretical physicists who claim time is merely an illusion, he can not fully understand the consequences of the information that he is providing that will, in spite of his denial, become part of the culture of medicine, of how we deal with aging.

I may have just ignored the excesses of the Nova program except my next door neighbor in our suburban San Diego community just happens to be a professor who is member of the international academic community that studies and writes about time, arguing that it is an illusion of our particular species. Since we chat about this while we are walking our dogs and picking up their shit, it sort of makes the issue more accessible, especially since he happens to be a very accessible guy. Out of my contention that "illusion" is not what time is anymore than our perception of color, one we have but our dogs don't, has come some insights. He mentioned that he enjoys the reaction to his use of the term illusion, as it gets people riled.

I gave him a hypothetical, a thought experiment, of a community of meteors in deep space that were destined to spend eternity simply following their orbits described by Newtonian and Einsteinian rules. I told him to assume they had cognition and if they talked about time, it truly would not exist, as the past and the future would both be known absolutely by the very same rules. There would be no now, as this concept only has meaning to those entities embedded in ecosystems describing the moment of the actor's action that affects all other systems of which they are in contact-in other words it is a concept of life, something that theoretical physicists try their best to ignore.

-snip-

In the Nova series, Brian Greene who produced the program, leaned quite a bit to the Wow aspect of the implications of quantum mechanics, giving the impression that Time Travel as described by H.G. Wells and many others was possible.

——————–

The efforts that I made, including corresponding with others of Greene's level of theoretical physics attainment who concurred with my views was worthwhile. This is a hot area among theoretical physicist and academics in philosophy of science. It is a group where no one is anxious to make the observation that the "Emperor has no clothes."

Andy Averill said,

December 30, 2012 @ 9:51 pm

@the other Mark P et al, the math was neither ridiculous nor meaningless, it just didn't have anything to do with this particular paper. And the participants weren't shown the whole paper, just the abstract. So unless they happened to know that "sequential effects" is only meaningful in psychology, it's hard to see how they could have been expected to catch on to the ruse. Nevertheless, the paper does make a worthwhile point, which is that people with advanced degrees are more impressed when research appears to be mathematically grounded, even if they don't understand the math themselves.

As for science journalism, it's not just in the English-speaking world that the quality is abysmal. I saw an article from a German paper a few years ago that argued that climate change was actually a good thing, because for every country that's going to be too hot, there's going to be one that will now be just right. So they'll be able to grow cotton in Canada, or something like that.

Nathan Myers said,

December 31, 2012 @ 4:09 am

Yeats was over-optimistic about the power of mathematics to prove Russell wrong, I think,…

But mathematics did prove Russell wrong. The proof led to the basis of computation theory.

[(myl) That's not what Yeats wanted to prove Russell wrong about.]

SusanC said,

December 31, 2012 @ 7:14 am

I suspect that some readers are indeed more swayed by mathematics than they should be, but this experiment is possibly a little unfair.

In some fields, "teaser" abstracts are common. The abstract promises something interesting that's going to appear in the paper, but leaves no clue as to how the trick going to be done. Usually, this is a deliberate rhetorical strategy, not an oversight. (And some fields, or journals, are less willing to let authors deploy this strategy).

The typical assumption is that the referees have read the entire paper before it was accepted for publication, and that the promised surprise result will indeed be delivered in the body of the paper. (If it isn't, the referees ought to have rejected it, possibly with really snarky comments).

So in these examples, a just about reasonable response (given only the abstract) is "I have no idea how they're going to fit that kind of model to that extremely unpromising subjhect matter, but it'd be kind of cool if they've pulled it off". (Whereas the response of the referees on reading the entire paper, and not finding the promised result, should be on the lines of "the authors are frauds/idiots").

I say "just about reasonable" because in this case it's weird enough that you ought to smell a rat just from the abstract.

=====

A possibly related issue: giving really large sample sizes unreasonable weight, given the confidence level. e.g. two versions of the paper, both of which reject the null hypothesis at the 95% confidence level, but one of which used a sample size of 100 and the other used a sample size of a million. You think the result with a sample size of a million is better, right? [Here, I'm assuming that the version of the paper with N=1E6 found a much smaller effect, leading to the same p value as the alternative paper with N=100 and a larger effect]

Stuart said,

January 1, 2013 @ 2:54 pm

" I conducted an online experiment with 200 participants, all of which had experience of reading research reports and a postgraduate degree"

I consider "whom" to be moribund, but in the above phrase it seems to me that "whom" would have sounded better than "which".

David J. Littleboy said,

January 2, 2013 @ 6:35 am

"[(myl) That's not what Yeats wanted to prove Russell wrong about.]"

Uh, no. I think it is. Goedel proved that any sufficiently powerful system could say things that you can't prove in it. Which is quite exactly what Yeats wanted.

Math-induced blindness « Brandon Seah said,

January 2, 2013 @ 9:28 am

[…] Language Log) About these ads GA_googleAddAttr("AdOpt", "1"); GA_googleAddAttr("Origin", "other"); […]

Robert Furber said,

January 10, 2013 @ 4:11 pm

@David J. Littleboy

Gödel proved no such thing. I refer you to Torkel Franzén's book "Gödel's Theorem: An Incomplete Guide to its Use and Abuse". Gödel's actual theorem has nothing to do with what Yeats wanted.