Hold the fort

« previous post | next post »

"State Department: 'Hold down the fort,' other common phrases could be offensive", Fox News 8/31/2012:

Watch your mouth — everyday phrases like "hold down the fort" and "rule of thumb" are potentially offensive bombshells.

At least according to the State Department.

Chief Diversity Officer John Robinson penned a column in the department's latest edition of "State Magazine" advising readers on some rather obscure Ps and Qs.

Here's Mr. Robinson's column, "Wait, What Did You Just Say?", from the July/August 2012 edition of State Magazine.

Robinson gives five examples of expressions that can give offense: "Black and Tan", "hold down the fort", "going Dutch", "rule of thumb", and "handicap". The first one is straightforward, as explained by Maura Judkis, "'Black and Tan' shoes force Nike apology", Washington Post 3/15/2012:

Nike thought the unofficial name for the shoe [released in honor of St. Patrick's Day] … referred to the drink, which mixes a pale ale beer and a dark beer — but it also is a name for a violent paramilitary group that suppressed the Irish during their war of independence in the early 1920s. In the Belfast Telegraph, Ciaran Staunton, president of the U.S.-based Irish Lobby for Immigration Reform, asked, “Is there no one at Nike able to google Black and Tan?”

The other four examples, however, seem to be somewhere between dubious and silly.

Here's what Robinson says about "Hold down the fort":

How many times have you or a colleague asked if someone could “hold down the fort?” For example, “Could you hold down the fort while I go to…” You were likely asking someone to watch the office while you go and do something else, but the phrase’s historical connotation to some is negative and racially offensive. To “hold down the fort” originally meant to watch and protect against the vicious Native American intruders. In the territories of the West, Army soldiers or settlers saw the “fort” as their refuge from their perceived “enemy,” the stereotypical “savage” Native American tribes.

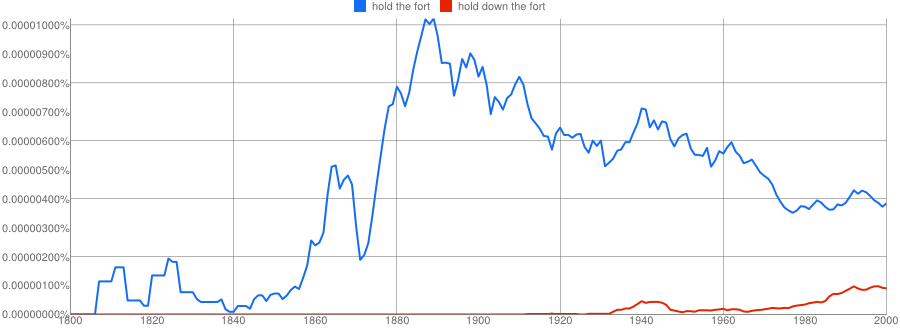

As far as I can tell, "Hold down the fort" is a relatively recent variant of "Hold the fort":

According to this page at cyberhymnal.org, the hymn "Hold the fort, for I am coming" was written in 1870 by Philip P. Bliss,

…after hearing Daniel Whittle relate the following incident from the American civil war:

Just before [William Tecumseh] Sherman began his famous march to the sea in 1864, and while his army lay camped in the neighborhood of Atlanta [Georgia] on the 5th of October, the army of Hood, in a carefully prepared movement, passed the right flank of Sherman’s army, gained his rear, and commenced the destruction of the railroad leading north, burning blockhouses and capturing the small garrisons along the line. Sherman’s army was put in rapid motion pursuing Hood, to save the supplies and larger posts, the principal one of which was located at Altoona Pass. General Corse, of Illinois, was stationed there with about fifteen hundred men, Colonel Tourtelotte being second in command. A million and a half rations were stored here and it was highly important that the earthworks commanding the pass and protecting the supplies be held. Six thousand men under command of General French were detailed by Hood to take the position. The works were completely surrounded and summoned to surrender. Corse refused and a sharp fight commenced. The defenders were slowly driven into a small fort on the crest of the hill. Many had fallen, and the result seemed to render a prolongation of the fight hopeless. At this moment an officer caught sight of a white signal flag far away across the valley, twenty miles distant, upon the top of Kenesaw Mountain. The signal was answered, and soon the message was waved across from mountain to mountain:

“Hold the fort; I am coming. W. T. Sherman.”

Cheers went up; every man was nerved to a full appreciation of the position; and under a murderous fire, which killed or wounded more than half the men in the fort—Corse himself being shot three times through the head, and Tourtelotte taking command, though himself badly wounded—they held the fort for three hours until the advance guard of Sherman’s army came up. French was obliged to retreat.

According to They Never Said It, this message was invented by reporters, no more trustworthy then than now, who combined two dispatches ("Hold out!" and "I am coming") into one ("Hold the fort! I am coming"). But in any case, it referred to holding the fort against Confederate soldiers, not against Native Americans.

There are some prior — entirely compositional — uses of the phrase, e.g. in An History of the Life of James Duke of Ormonde, 1736:

That the Lord Esmond Governor of the fort of Duncannon, having agreed with the Irish for a Cessation of a few days on some other pretence, sent a person of trust to the Treaty in the beginning of September, with letters of credence; on the back of which that person certified under his hand, that the store there was so exhausted, and the Officers and soldiers in garrison had already suffered so much extremity through want, that it was not possible for him to hold the fort above ten or fourteen days longer, and therefore earnestly desired, either immediate supplies, or that some speedy course might be taken for the preservation of that important place.

Or, found in a search of COHA, two examples from an 1827 novel The Buccaneers by Samuel Judah:

It was a summons from the new governor, that those who held the fort should straitways come forth and deliver it up peaceably to his possession; otherwise they should be held as traitors to the king …

I do not hesitate to say that his holding the fort against his Excellency Colonel Sloughter, the governor, is an open and intended act of rebellion for which alone the severest punishment that can be inflicted he deserves to suffer …

There are 20 other examples before 1900, a plurality of them being references to the hymn, and none of them referring to Native Americans.

As for the "hold down the fort" variant, I was not able to find any evidence of an origin related to Indian wars, or even of any significant amount of use in that connection. The earliest example that Google Books knows about seems to be in a 1948 edition of Billboard magazine, in the Coinmen You Know section:

The earliest example in the ProQuest Historical Newspapers seems to be an article from the LA Times on April 24, 1927, which begins

Two of the best bantamweights in the country will hold down the fort at the Hollywood American Legion Stadium Friday night. Midget Mike O'Dowd of Columbus, O., will fight it out with Bad News Eber of Montreal, Can.

The next oldest citation is from the Washington Post, July 31, 1927:

One month more an the theater comes into its own. After the dog days of August comes the sharpening of September blades. The thrust is about to be made.

Along the heated asphalt of Broadway, acresses and actors hie to managers' offices in search of work. In the meantime, stock companies hold down the fort.

All of the other 10 pre-1950 examples are metaphorical, and none of them mentions Native Americans.

A search of Proquest American Periodicals (a collection that starts in 1740) found one example in a western tale: Wm Macleod Raine, "Crooked Tails and Straight", which appeared in 1924:

But this story is entirely about horse-thieves, train robbers, cattlemen and sheepherders — plenty of stereotypes, but no Indians are mentioned at all.

The same story shows up in a search of COHA, dated 1936 — COHA's other examples of {[hold] down the fort} are all later, and all metaphorical.

So if this phrase "originally meant to watch and protect against the vicious Native American intruders", this original meaning seems to have left no traces that I can find in any newspapers, magazines, or books. I strongly suspect that Robinson's "historical connotation" story is a recent invention.

This has gone on long enough, so I'll just refer you to Wikipedia for "going Dutch", and to Cecil Adams' debunking of the "rule of thumb" nonsense. As for handicap, John Robinson says:

There is no absolute verification as to the historical roots of the word “handicap.” However, many disability advocates believe this term is rooted in a correlation between a disabled individual

and a beggar, who had to beg with a cap in his or her hand because of the inability to maintain employment.

The OED says:

Etymology: A word of obscure history. Two examples of the n., and one of the verb, are known in 17th cent.; its connection with horse-racing appears in the 18th; its transferred general use, especially in the verb, since 1850. It appears to have originated in the phrase ‘hand i' cap’, or ‘hand in the cap’, with reference to the drawing mentioned in sense 1.

The role of the cap is explained this way:

The name of a kind of sport having an element of chance in it, in which one person challenged some article belonging to another, for which he offered something of his own in exchange.

On the challenge being entertained, an umpire was chosen to decree the difference of value between the two articles, and all three parties deposited forfeit-money in a cap or hat. The umpire then pronounced his award as to the ‘boot’ or odds to be given with the inferior article, on hearing which the two other parties drew out full or empty hands to denote their acceptance or non-acceptance of the match in terms of the award. If the two were found to agree in holding the match either ‘on’ or ‘off’, the whole of the money deposited was taken by the umpire; but if not, by the party who was willing that the match should stand.

No begging is involved.

I can echo Ciaran Staunton's question about Nike, and ask "Does no one at the State Department know how to do a web search?"

Update – And I'll promote from the comments my observations that "this kind of nonsense plays into the hands of people who would like to ridicule everything associated with the word 'diversity' as absurd over-sensitivity to invented offenses and imaginary barriers", by "pasting a big 'KICK ME' sign on your back for the benefit of those who want to believe that diversity concerns are just exaggerated (and ignorant) political correctness."

Uly said,

September 2, 2012 @ 5:03 pm

Of course, there is a good point here. If enough people believe the silly stories and find the terms offensive in the here-and-now, it's probably wise to avoid them anyway just because it's not worth fighting it out every time you want to say something.

[(myl) That's a reasonable position, though it's a form of the "crazies win" doctrine, which some people object to across the board, and others try to limit to cases where the crazies really have won. But Mr. Robinson's column doesn't say "some people falsely believe that hold the fort originates in racist stereotyping of Native Americans as savage attackers, and so you should be careful in using that expression". Instead, he says "To 'hold down the fort' originally meant to watch and protect against the vicious Native American intruders." This is joining the crazies, not just promoting "crazies win".

And more to the point, it's pasting a big "KICK ME" sign on your back for the benefit of those who want to believe that diversity concerns are just exaggerated (and ignorant) political correctness.]

Q. Pheevr said,

September 2, 2012 @ 5:39 pm

Speaking of "reporters, no more trustworthy then than now," it's interesting to see how a magazine column written by one State Department official turns into "according to the State Department" in the hands of Fox News. The column itself is clearly misguided and etymologically uninformed, but unenlightened blathering about language is (alas) not so rare in magazine columns as to be particularly newsworthy.

I sort of suspect that Fox News would like people to get the impression that the column somehow represents official State Department policy, or that some kind of censorship is being imposed. That doesn't seem to be the case, and I'd propose amending the question at the end of this post from "Does no one at the State Department know how to do a web search?" to "Does no one at State Magazine know how to do a web search?"

rootlesscosmo said,

September 2, 2012 @ 5:41 pm

The song (I hadn't known it as a hymn) "Hold the Fort" made it into the People's Song Book in the 1940's, partly, I think, because its second line, "Union men, be strong!" carried both a pro-Union and a pro-union meaning.

Henning Makholm said,

September 2, 2012 @ 5:53 pm

Haven't people everywhere been holding forts and other defensive structures for thousands of years before Columbus? The corresponding Danish idiom has people holding a redoubt rather than a full fort, and while it definitely has connotations of war, there seems to be no particular group of enemies the fort/redoubt is being thought of as held against. Definitely not Indians here — but possibly Prussians, and whatever you'd like to call those, "savage" isn't a word that comes to mind.

GeorgeW said,

September 2, 2012 @ 5:59 pm

Even assuming that Robinson were correct (which MYL has refuted), this assumes that one is responsible for obscure etymologies of idioms that even those who could be offended would also not be aware of. This is just silly.

Soris said,

September 2, 2012 @ 6:24 pm

"Handicap" seems to me to be different from most of those examples, in that it actually does offend many of the people Robinson claims it is derogatory towards. It fell out of use here in Britain many years ago, and I was actually slightly shocked when I first visited the US and found it was still the standard term.

But I don't recall Robinson's supposed etymology being used much as an argument against it; what I remember being argued is that "handicapped" was too closely associated with oldfashioned attitudes towards disability, quite out of place in a modern Britain that was requiring public buildings to install access ramps and so forth. The argument, as I recall it, was basically about connotations, not etymology.

I suppose that kind of thing is just too vague and illogical for some people, so they look for just-so stories instead?

Jerry Friedman said,

September 2, 2012 @ 8:07 pm

The OED connects "go Dutch" to "Dutch lunch, party, supper, treat", all of which are in a section of uses where "Dutch" means "Characteristic of or attributed to the Dutch; often with an opprobrious or derisive application, largely due to the rivalry and enmity between the English and Dutch in the 17th c." As "Dutch treat" is the earliest and as it means a "treat" where no one is treated, I'd say it is opprobrious. I'll let the Dutch people here decide how opprobrious. (I might rather unfairly add, though, that the Wikipedia article lists many equivalents in other languages that mean things like "American sharing", and I'm not very offended.)

Andy Averill said,

September 2, 2012 @ 8:23 pm

"Going Dutch" means pretty much the same as "Dutch treat", doesn't it? Even if nobody knows for sure the original derivation, it seems highly likely to be some kind of slur against the Dutch. But does anybody even use either of these expressions anymore? I can't remember the last time I heard them.

Kate G said,

September 2, 2012 @ 8:49 pm

It's been my experience that in the US Dutch means "not really" or "false" – Dutch treat, doors, courage, and uncle come immediately to mind – whereas in the UK it is French that holds this position – for doors, toast, and (ahem) letters. That's what makes it derogatory, if in fact anything does.

Morten Jonsson said,

September 2, 2012 @ 9:00 pm

@ Kate G

I don't think there's ever been anything derogatory about either Dutch or French doors. They're simply alternative kinds of door. Or about French toast, for that matter, which I'm sure even the English agree is delicious.

J.W. Brewer said,

September 2, 2012 @ 10:01 pm

Mr. Robinson does have a general disclaimer that the authenticity of many of the supposed stories of origin he gives is disputed. And e.g. the "rule of thumb" discussion is prefixed with "[m]any women's rights activists claim," which cynical readers might perceive as casting some doubt on the veracity of what follows. So he may be just taking a "crazies win" approach. Or confirming not so much negative stereotypes about political correctness as negative stereotypes about the State Department as being in the business of appeasing the unreasonable and thus incentivizing them to be even more unreasonable in the future. But even on a "crazies win" approach there's a missing piece. Let's stipulate that certain expressions of the form "Dutch X" are rooted in pejorative anti-Dutch attitudes of the 17th century. It does not follow from that that there is any meaningful number of Dutch activists out there today who will actually take offense. There might or might not be, but that is a separate empirical question from the etymological question.

Mark F. said,

September 2, 2012 @ 11:05 pm

Do any Dutch readers have opinions on "Dutch treat", etc?

Jeroen Mostert said,

September 3, 2012 @ 1:17 am

What rankles me is that even *if* etymologies of the "hold the fort" kind were true, why on Earth should this be considered offensive? If "hold the fort" indeed comes from the Civil War era, would that make it offensive to Southerners since their ancestors were the ones against which the fort was being held? Are we really making the argument that holding a fort against someone is offensive because it portrays one party as the enemy of another? You can't imply that a conflict that actually occurred was, in fact, a conflict? The connotations of "savage" Native Americans are being explicitly dragged in by the would-be etymologist — it offends exactly those people who wish to be offended.

@Mark: I'm Dutch and I find the expressions involving the Dutch mildly amusing because generally, the modern reputation of the Dutch is that we're a very inoffensive people — the kind who don't deserve the vitriol of cultural slurs. The bitter history between the Dutch and the English is from another era altogether, and the role of the Dutch in shaping American culture isn't well-known over here beyond perhaps knowing that "even old New York was once New Amsterdam". To even be immortalized in English is a sort of dubious honor. When I first heard these expressions, finding out why we were even mentioned in the first place was more interesting than taking offense.

"Going Dutch" is completely inoffensive because, well, that's what we Dutch really do, and we think nothing negative about it. "Dutch treat" is obviously mean-spirited, but still not something I'd take offense at because the meanness is historical, not current. I've never seen anyone use any of the "Dutch" expressions to explicitly insult the Dutch, and "anti-Dutch sentiment" is something uncommon enough to be used as a joke. No doubt someone can use it to give offense, and no doubt some people would stand at the ready to take it, but overall we're probably flattered to be commemorated at all.

Jeroen Mostert said,

September 3, 2012 @ 1:52 am

At the same time, however, I should note that precisely *because* the Dutch are an unlikely target for offense, the "Dutch X" examples are misleading. You can't point at "well the Dutch don't think 'going Dutch' is offensive, do they?" and use this to draw any sort of conclusion about how other expressions actually give offense, or ought to give offense.

As J.W. Brewer says, you're down to empirical questions that have nothing to do with linguistics. "Dutch treat" is an expression that is designed to offend, even if it doesn't. "Hold the fort" is an expression not designed to offend, even though it might (but does not, other than in some people's imaginations).

[(myl) In my opinion, you're taking an excessively narrow view of what "linguistics" should mean. There certainly are some empirical questions, but I object to the notion that empirical questions of etymology have nothing to do with linguistics, or that empirical questions of connotation in production and perception have nothing to do with linguistics. The policy questions — whether to avoid giving possible offense to a few people with a wrong idea about what "hold the fort" or "rule of thumb" means — are also partly linguistic questions, in the same sense that public health measures and vaccination campaigns are partly biomedical questions.]

Aaron Toivo said,

September 3, 2012 @ 2:03 am

On the "crazies win" argument, I don't know. Early in the process that may be a reasonable attitude to take. But later on… however arrived at, and however distasteful, semantic shift is semantic shift. So when it becomes widespread for people to feel that a phrase means X, then it becomes the etymological fallacy to insist that the real etymology Y should bear on the offensiveness of the phrase.

[(myl) But in none of the four cited examples is it yet "widespread for people to feel that a phrase means X". So one question at hand is whether the spread of false or irrelevant etymologies, and associated socio-political attitudes, should be encouraged.

A more important issue, in my opinion, is that this kind of nonsense plays into the hands of people who would like to ridicule everything associated with the word "diversity" as absurd over-sensitivity to invented offenses and imaginary barriers.]

Frans said,

September 3, 2012 @ 5:21 am

What, exactly, would the alternative be anyway? You go to a restaurant, some people get something cheap and others get something expensive, and you all share the bill equally? A sexist notion like a man always paying for a date instead of either sharing the bill or alternating? Perhaps it's because I am Dutch, but if anything it sounds like a compliment for not being a push-over who lets themselves be pressured into subsidizing wasteful faux-socialists.

PS We do allow e.g. our parents and our in-laws to pay for dinner, lest anyone wonders about that. I really don't think there's any significant difference with other countries here, or at least with Belgium, Germany, Scotland, and the US.

GeorgeW said,

September 3, 2012 @ 5:55 am

@Jeroen Mostert: ""Dutch treat" is obviously mean-spirited, but still not something I'd take offense at"

As a native speaker of English, I have never thought of the expression as mean spirited. I have used it at times to alleviate the other person from thinking they should pay in situations in which they might feel they should be paying, particularly when they did the inviting.

[(myl) These days, "Dutch treat" seems to be in the category of expressions like "It's all Greek to me", which (though a bit silly as an expression) doesn't imply that Greeks are incoherent or outrageously foreign. Though a country-name is obviously involved, I don't think that people who use the phrase today generally make any consequential connection (negative or positive) to the country and its people.]

Stephen Goranson said,

September 3, 2012 @ 6:58 am

Here's another early use of "handicap":

"After this we drank very smartly, but, I forgot not all this while my design on him. After that I had pitied him, and lamented his sad misfortune, I thought it high time to put my Plot in execution, in order thereunto I demanded what difference he would take between my Hat and his, his Cloak and mine, there being small matter of advantage in the exchange, we agreed to go to [H] handicap. In fine, There was not any thing about us of waring cloaths but we interchanged, scarce had I un-cased my self, and put on my Friends cloaths, but in came one that had dogged me, attended by the Consta|ble, with a Warrant to seize me, who they knew by no other token but my Boarding-Mistresses Sons garments, I had stolen for my escape."

Head, Richard, 1637?-1686?

The English rogue described, in the life of Meriton Latroon, a witty extravagant Being a compleat discovery of the most eminent cheats of both sexes. Licensed, January 5. 1666. 1668

Bib Name / Number: Wing (2nd ed.) / H1248 [EEBO]

Alan Gunn said,

September 3, 2012 @ 7:22 am

There are so many negative phrases using the word "Dutch" that when I learned to fly I assumed that the phrase "Dutch roll" began as a slur, too. (A Dutch roll involves rocking the wings back and forth with the nose held on a straight course and the tail swinging back and forth.) It turns out , though, that it derives from a rolling motion characteristic of Dutch sailing ships back in the day. I've also wondered about "Chinese pass" (flying straight in a crosswind with the wing on the side from which the wind is blowing held low).

Even if these terms and others like them did come from negative stereotypes about people of particular nationalities, does it continue to matter if prejudice against the group in question has all but disappeared? Saying someone has "welshed" on a bet may once have been a reference to the supposed dishonesty of the Welsh (no one seems to know for sure). I doubt that there are Americans who think poorly of the Welsh today (don't know about the English). If so, one shouldn't think somebody using the term meant to say bad things about the Welsh. Same (in the U.S., anyway, though not in England) for "Irish dividend" and the like, referring to a people once widely despised but now claimed as ancestors by most of us on March 17.

Jeroen Mostert said,

September 3, 2012 @ 7:40 am

@myl: IANAL — where the "L" doesn't stand for "lawyer" in this case. I defer to your opinion on what linguistics is. If my view is too narrow, it's only because answering questions on whether or not particular expressions are offensive and who they're offensive to is not the kind of linguistics I'm much interested in. But certainly, if it's not linguistics it's hard to say what else it could be.

@GeorgeW: when the expression was coined, it was obviously mean-spirited. It's a treat that's not a treat at all, implying there's something wrong with the originator's generosity. I have no idea whether or not it originally was more teasing than insulting (my money, if I had any to bet at all as a stingy Dutchman, would be on the former). Of course, in contemporary English, nobody bats an eyelash at it anyway.

mollymooly said,

September 3, 2012 @ 7:58 am

Snopes Urban Legends Reference Pages has a category for this.

[(myl) Or, more specifically, here. I like their quotation from Abram Smythe Palmer, Folk-Etymology: A Dictionary of Verbal Corruptions Perverted in Form or Meaning, By False Derivation or Mistaken Analogy:

"The fact is, man is an etymologizing animal. He abhors the vacuum of an unmeaning word. If it seems lifeless, he reads a new soul into it, and often, like an unskillful necromancer, spirits the wrong soul into the wrong body."

]

Elizabeth said,

September 3, 2012 @ 8:18 am

I recently got walloped on Facebook for pointing out the French origin of 'picnic,' after several people vowed never to utter it again having learned of its racist origins. I was told that this is how racists work nowadays: they point out the 'correct' etymology. I understand how words get skunked (like niggardly) but why wouldn't someone be relieved to learn that a word came from perfectly innocuous origins? Why buy the nonsense so eagerly?

[(myl) My unsupported guess would be that "knowledge" of false offensive etymologies is a form of social capital.]

Theophylact said,

September 3, 2012 @ 8:32 am

There's a Tom Sharpe novel (perhaps Ancestral Vices?) in which an illiterate, malignant little man is referred to as a "dwarf". The social-worker protagonist "corrects" the term to "Person of Restricted Growth". Halfway through the book this has become "P.O.R.G.", and by the end it's become the highly offensive four-letter word "porg". Euphemisms always become polluted by the reality of the thing they're meant to sanitize.

Dave K said,

September 3, 2012 @ 8:46 am

Theophylact, it's more that euphemisms become polluted by the popular perception of the thing they're meant to sanitize.

J.W. Brewer said,

September 3, 2012 @ 9:27 am

I do not vouch for the following anecdote's accuracy (by the controversial music-world figure Steve Albini), but I do recall reading it in print decades ago and someone has transcribed it on the internet for easy cutting and pasting:

I met a writer for the Dutch music magazine Oor (Ear), who always wore a glove on his right hand, which was always balled-up in a fist. I found out why when the conversation turned to fireworks, and he demonstrated (by sticking a thumbtack in it) that his hand was wooden. He had blown it off with fireworks as a boy. He asked me why Americans have such a low opinion of the Dutch. I told him that Americans seldom even thought of the Dutch, except for their elm disease, which we thought highly of. He gave as evidence the expressions “being in Dutch,” “Dutch courage,” and worst of all, “Dutch treat— why that’s no treat of all!” I told him that they were all puns.

[(myl) Let's not forget "Double Dutch! And Dutch ovens are a Good Thing, too!]

Brett said,

September 3, 2012 @ 9:43 am

@J.W. Brewer: That quote is interesting in that the Dutch writer focused on American attitudes toward the Dutch, based on those three expressions, none of which is something I, as an American would use. That's not because any of them might be perceived as offensive, but for various reasons they are not part of idiolect. The first, "being in Dutch," I was totally unfamiliar with until just now. The second, "Dutch courage," I have only encountered in British writing (and never in speech). The third, "Dutch treat," I have encountered, but it sounds quite dated. (Honestly, I think the first encounter I had with this variety of "Dutch" expressions was reading the e-bay rules for Dutch auctions.)

While I was aware the "Dutch courage" was obviously pejorative, I did not perceive anything negative about "Dutch treat" until the discussion today (not ever having thought about it much). The pejorative meaning is more clear if you know that the "treat" version (as opposed to, say, "going Dutch") is the oldest form of this expression, but I doubt most users are aware of that. As I mentioned above, I first encountered this constellation of expressions in "Dutch auction," although I could recognize that the meanings related to who pays for dinner were older.

J.W. Brewer said,

September 3, 2012 @ 10:14 am

Dave K.: I think that's largely true (the "popular perception" point) but there are two sides to it. A particular word/phrase may have come to be used in a derogatory fashion even if it started out as the polite/euphemistic word for the (socially-marginal) group in question (e.g. "retarded" may have started out as a polite/quasi-scientific word to describe developmental delays in children but by the time of my own childhood had morphed into a playground insult). Or (not that these are always mutually exclusive) some politically-salient fraction of members of the group in question may a) come to feel that the word/phrase has taken on the negative baggage of their problematic social situation even if outsiders continue to use it primarily in situations where they are being, by their own lights, polite and respectful (which of course could still be interpreted on the other side as patronizing/condescending); AND b) believe that getting everyone else in society to start using a new and different word/phrase would itself change things and improve the group's social situation. The second half seems to have a lot of magical thinking and perhaps pop-Whorfian assumptions built into it, and has always reminded me of an anecdote I heard in an undergraduate sociolinguistics class about an ethnolinguistic group (maybe somewhere in or near Indonesia?) where if a child got really sick you changed the child's name and everyone in the community made sure never to use the old name, which so confused the evil spirits which were causing the disease that they would leave the child alone. But this gets us back to the crazies-win problem, and the fact that many many people of political salience in our society have strongly held views on matters about language that are at odds with the scientific view of the same issue that the tiny minority with formal training in liguistics would be likely to hold. But then it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy so that e.g. it really is the case that "gay" and "homosexual" are not pure synonyms because they have different connotative overtones. Thus, "handicap[ed]" in a non-golf context may have as an empirical matter fallen into the same semi-taboo zone as e.g. "Negro," even if through no fault of its own.

People who work for the State Department should actually be aware of genuine taboos and how they vary in order both to avoid gaffes ("Eskimo" can be taboo in Canada in a way it isn't in the U.S., and we should expect the staff of our Embassy in Ottawa to have been taught that) and perhaps to roll with the punches if they hear someone use a word/phrase that has become taboo in AmEng but is still current in the variety of English spoken in some other country where they are stationed. But you can do that w/o unnecessarily multiplying the number of actual taboo words/phrases, and w/o promoting bogus etymological explanations/justifications for a social phenomenon which is not necessarily or consistently based on accurate historical understandings of the things that become taboo.

Paul O said,

September 3, 2012 @ 10:22 am

…tempest in a teapot. (I hope that doesn't offend the British)

The firestorm in the 90s over the word "niggardly."

I was told, ironically, by a co-worker, "I refuse to allow blacks to be denigrated by the use of 'niggardly'."

Jimbino said,

September 3, 2012 @ 11:26 am

I always understood "Dutch" to be and American mispronunciation of "Deutsch" as in "Pennsylvania Dutch," who are of German extraction.

As far as "going Dutch," I found it one of the distinct pleasures of Germany that the women were accustomed to paying for themselves on a date, casual or otherwise.

Alan Gunn said,

September 3, 2012 @ 11:44 am

Jimbino: Many Americans once used "Dutch" to refer to Germans. My paternal grandmother, whose maiden name was German and whose family came from Pennsylvania, thought she was of Dutch descent, though I'm pretty sure it was German, Austrian or Swiss (partly because her surname does not appear at all in the Amsterdam phone book, though it is common in Germany etc.). A few years back my wife and I and some of her relatives from Germany were having lunch in a restaurant and our teenage Mennonite waitress asked us what language we were speaking. We said, "German," and she expressed surprise that she could understand us. A few years ago, Indiana was reported to have the highest percentage of native speakers of Dutch of any state. Turned out this was Amish and Mennonite people reporting that the language they spoke at home was Dutch.

I think, though, that we got many of the pejorative phrases involving "Dutch" from the British, who I believe were usually better at distinguishing Dutch people from Germans than we were.

ALEX MCCRAE said,

September 3, 2012 @ 11:54 am

J. W. Brewer,

Following up on your noting the subtle connotative variance in the meaning of the related, yet not necessarily totally synonymous, 'labeling' words "gay" and "homosexual", one could add the word "queer" to the discussion.

(Curiously, back-in-the-day, it appears that the pioneering LGBT community had adopted the term "gay" to denote their particular same-sex, or homosexual relationship dynamic, as a kind of amplification of the formerly innocuous word "gay", as in the phrases "gay apparel" from the popular Xmas carol, or "gay nineties", as a specific frolicking decade in American history. (Neither usage, particularly having any relationship to the 'co-opted', same-sex connotation of the word "gay'.)

Interestingly, in its earliest, most common incarnation, the word "queer" meant "odd", or "unusual", or perhaps, "eccentric". But in our so-called modern era, homophobes and gay-bashers alike would often use the term "queer", as in "you f****g queer", as a derogatory, demeaning, intending-to-hurt epithet against a perceived homosexual, often in the public domain, and directly spewed into the individual's face. In other words, "queer", coming as a sexual slur from the so-called straight community was always perceived by the greater community (not just gays) as a negative, offensive, demeaning term directed at gay folk.

Over time, as same-sex relationships became more open (and less closeted), and socially acceptable by at least the more liberal, (or shall we say enlightened and tolerant), elements of the wider 'straight' community, gay folk kind of flipped the meaning of the word "queer" around to have a more positive, prideful connotation.

Yet somewhat in the same vein as to how the N-word has become acceptable when used in say light conversational banter amongst black folk, it appears that the word "queer", (the Q-word?) as a word connoting positivity, gender pride, and sexual identity is still most positively acceptable, (and frequently used), amongst members within the gay community—- now more a badge of personal pride and positive identification, and no longer a taboo, or offending word.

If today, say a straight person, in anger, in a menacing tone, called a gay individual, "queer", the target of that epithet would clearly not take it as a compliment. In other words the source of the word, the tone in which it was delivered, and the context of the situation can carry a lot of emotional weight, positive, or negative, in these social transactions.

With the current rise in gay pride, and the dispelling of a lot of the hysteria, myth, and false-truths regarding homosexuality in the last few decades, as well as the broadcast media's airing more gay-themed shows, (or at least offering shows w/ say not merely a token gay character), IMHO a lot of the negative stigma, and ugliness surrounding the word "queer" has fallen away.

Case in point, the airing of the fairly successful cable TV reality show "Queer Eye for the Straight Guy", which ran for several seasons, where three openly-gay fashion make-over 'experts' attempt to take a straight male w/ zero fashion sense, and basically transform him into a GQ-level fashion plate.

Twenty-five years ago, TV wouldn't have touched a show like this w/ a ten foot pole. (Admittedly, more permissively-inclined cable TV wasn't even around a quarter-century ago.)

As Bob Dylan once sang, "The times…. they are a changin'."

Jeremy Wheeler said,

September 3, 2012 @ 11:58 am

Speaking as someone who was for many years involved in teaching about discrimination and 'diversity', I thoroughly agree with Professor Liberman's points that 1. "…it's pasting a big "KICK ME" sign on your back for the benefit of those who want to believe that diversity concerns are just exaggerated (and ignorant) political correctness." and 2. "…that "knowledge" of false offensive etymologies is a form of social capital."

Both are demonstrated in this report from the traditionally conservative newspaper, The Daily Telegraph, about the expression 'nitty gritty', which has been given a false etymology, namely that it refers to conditions on the lower decks of slave ships: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1394248/Nitty-gritty-is-not-PC-minister.html

The first of Professor Liberman's points is demonstrated by the overall tone of the article; the second by the attitude of the police officer, when he says: "As a serving police officer, if I used the term nitty gritty, which you used a moment ago, in our modern politically correct society I would be facing a discipline charge. Nitty gritty is a prohibited term in the modern police service as being a racist term."

He might just as well have added, "So there!"

michael farris said,

September 3, 2012 @ 1:12 pm

It looks like no one else has, so I'll just provide the link for the following anti-Dutch hate literature from the group Americans United to Beat the Dutch:

http://web.archive.org/web/20031211010156/www.nationallampoon.com/dutch/dindex.html

CuConnacht said,

September 3, 2012 @ 1:46 pm

The union song "Hold the Fort" put new lyrics to the hymn tune.

J.W. Brewer said,

September 3, 2012 @ 2:48 pm

People like myl and Jeremy Wheeler who are concerned about the kick-me-sign factor may need to consider the processes by which people end up in positions like "Chief Diversity Officer" and/or heads of the sort of outside advocacy groups that governmental agencies and corporations seek to avoid getting embroiled in controversies with. Are those processes (in terms of who ends up being interested in pursuing that sort of career and in terms of how senior management chooses among candidates to fill openings) selecting for or against a healthy degree of skepticism regarding etymological claims of this sort (the sort that gives rise to the instinct to check out anything that sounds "too good to be true")? Are they selecting for or against possession of the "social capital" that arises in some circles from possession of bogus information of this sort?

Mark F. said,

September 3, 2012 @ 3:34 pm

@Jeroen Mostert – That's pretty much what I thought.

@Jimbino, Alan – The OED entry on "Dutch" is interesting. Use of "Dutch" for "German" (or for "German including modern-day Dutch as a subset") goes way back. Apparently, "Dutch treat" first appears in the late 1800s in America, which makes me start to think it might not share the same origin as the other Netherlands-disparaging terms. Maybe it's actually disparaging of German immigrants to the US.

Theophylact said,

September 3, 2012 @ 4:45 pm

Dave K, some things can't be papered over. Death, torture and tits will always have new euphemisms to replace the old ones.

Robert Coren said,

September 3, 2012 @ 8:11 pm

@Paul O: I'm not sure, when you say "I was told, ironically, by a co-worker…", whether you mean that the co-worker intended the remark ironically, or that you find it ironic that (s)he made the remark. I'm leaning toward the former.

Robert Coren said,

September 3, 2012 @ 8:20 pm

@Alan Gunn: As to "welsh", etc.: This can get a bit tricky. What about "Indian summer" or "gyp"? The person using these words may well not realize their origins or have any prejudice against Native Americans/Indians or Roma/gypsies, but these are both groups that do still suffer from discrimination. While it seems unlikely that many Dutch people would be deeply offended by "Dutch treat", I wouldn't be so sure that a Native American wouldn't be offended by "Indian summer", or especially "Indian giver".

It probably doesn't help that the words "Indian" and "gypsy" are themselves derived from false ideas about the origins of the people being referenced.

Rod Johnson said,

September 3, 2012 @ 8:53 pm

Alex–This is kind of a tangent, but cable has actually been around for a long time in the US. HBO started in the mid-sixties and was national by the time of the Thrilla in Manila in 1975. And I spent god knows how many hours watching MTV in the early 80s (as well as trying to peek at scrambled Playboy Channel programming). "Queer as Folk" premiered in the UK in 1999. (Not disagreeing with your post, I just wanted to point out that "adult" programming on cable is older than people sometimes think.)

J.W. Brewer said,

September 3, 2012 @ 9:53 pm

Wikipedia gives at least five different conjectural etymologies for "Indian summer," from which I infer that no one, including Robert Coren, actually knows the origin of the expression. This creates the sort of vacuum in which speculative or unsubstantiated claims of offensiveness can thrive given appropriate social conditions. As a practical matter, Indian summer is stereotypically viewed as an affirmatively pleasant thing to experience whereas an "Indian giver" is stereotypically viewed as unpleasant, which you might think would have some impact on their relative chances of survival as phrases usable in polite company.

On the other hand, my daughters went to nursery school after the historical tipping point when "Indian style" describing a mode of sitting on the floor had been replaced in local nursery-school-teacher dialect by the neologism/euphemism "criss-cross apple sauce," which wiktionary actually has an entry for. Perhaps not a huge loss, but since "criss-cross apple sauce" seems difficult to say with a straight face when you are no longer a young child or speaking to an audience of young children, I'm not sure what my daughters' generation will do if they need to describe this mode of sitting when they are older. I recall hearing a few people in college in the 1980's using the intermediate form "Native American style" in a way that was sorta-jocular but not entirely, and perhaps evidenced what myl has called in other contexts "nervous cluelessness" about what is safe to say without getting in some sort of trouble.

Q. Pheevr said,

September 3, 2012 @ 10:38 pm

Perhaps they'll either discover or reinvent the expression "cross-legged." (Or "tailor-fashion," but that's less transparent.)

Frank Y. Gladney said,

September 4, 2012 @ 12:12 am

Indian summer is something nice, right. I thought so until I noticed that the Russian counterpart is _bab'e leto_ 'woman's summer', a slur on women. So Indian summer is a slur on Native Americans, like Indian giver! (you gave it and now you're taking it back).

Xmun said,

September 4, 2012 @ 1:13 am

The "Indian" of "Indian summer" refers to the summer as it's experienced in India. Nothing to do with Native Americans!

Xmun said,

September 4, 2012 @ 1:38 am

Beg pardon. I take that back. I was remembering what I had been told in my (British) schooldays, but my reference books — belatedly consulted — contradict that idea.

John Walden said,

September 4, 2012 @ 2:13 am

There seems to be a process whereby a word starts off with an offensive or stereotyping intent, then this is "bleached", perhaps for a long time. Sometimes this is followed by most people waking up to its potential to offend and its falling into disuse.

The tricky moment is when not everybody has seen the potential.

Back in the 60s we used "to jew" as a verb meaning "to cheat" and I don't think it was just because we were unthinking children: it certainly wasn't one of the many words that we'd be told not to use by adults. I don't think they in turn gave a second thought to its "meaning". But I doubt if anybody uses the word, even in private, these days without it being deliberate and without its slurring connotations being to the forefront.

Where does that leave "gypped"? I certainly use the word without thinking "Oh, yes. Gypsies".

Alan Gunn said,

September 4, 2012 @ 7:20 am

@ Robert Coren: Yes. I think "welsh" is an easy case because I can't imagine anyone (in this country) harboring anti-Welsh prejudice. Even so, very negative phrases, like "Dutch treat," might be thought undesirable even if the group in question seems clearly not to be the object of bigotry. I'm inclined to think that expressions involving the Irish are exempt even from that restriction, as just about everyone (Britain excepted, to be sure) is genuinely fond of the Irish, and also, perhaps, because insulting comments are often taken as good-natured among the Irish themselves. (Many years ago, when visiting the sister of an Irish friend, I realized she liked me when I was greeted after sleeping late with "So there you are you lazy pig!") Here, as elsewhere, context matters a lot, and the question should be what a reasonable listener would infer about the speaker's attitude toward the people in question. For "welsh," the answer would be "nothing." "Indian giver," "Jew down," and the like are very different. "Gyp" is a close call, because who remembers the origin of the word unless reminded? It's not a word I use myself, but it seems uncharitable to assume that anyone who does hates Gypsies. It's a good idea to give people's words a charitable interpretation whenever possible. Even with phrases I wouldn't use myself, I like to think I'd take the person speaking as doing so out of ignorance rather than malice in the absence of other evidence.

RP said,

September 4, 2012 @ 8:27 am

Commenters here seem to be assuming that "gyp" comes from the word "gypsy". This seems unclear, since oxforddictionaries.com specifically says "origin uncertain" ( http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/gyp?q=gyp ), while the OED mentions two possibilities, only one of which "gypsy". Why should people jump to assume that the offensive origin is the genuine one?

"Welsh"/"welch" also has uncertain origin.

J.W. Brewer said,

September 4, 2012 @ 9:09 am

Just to be sure that no anti-Welsh bigotry arises in the U.S., one of my daughters was taught a bowdlerized version of "Taffy was a Welshman, Taffy was a thief, etc." in elementary school, in which Taffy is simply a "bad man."

Joe Green said,

September 4, 2012 @ 9:40 am

@Paul O:

No, it couldn't possibly, not least because we say "storm in a teacup".

Thomas Thurman said,

September 4, 2012 @ 9:55 am

It was always "cross-legged" when I was at school in England in the eighties.

I once had to dig out a dictionary to demonstrate that the "gyprooms" in Cambridge colleges were no sort of slur against the Romany.

Allen said,

September 4, 2012 @ 10:14 am

The actual article does say: "Much has been written about whether the etymologies are true or merely folklore, but this isn't about their historical validity; instead, it is an opportunity to remember that the choice of wording affects our professional environment."

(viewable online at: http://digitaledition.state.gov/publication/?i=119665 ). That the etymologies or explanations are spurious doesn't invalidate his point.

M.R.Forrester said,

September 4, 2012 @ 10:23 am

@Frans: In East Asia, people do pay for meals differently. In any formal and most informal situations, there's a host who pays the bill. This is the person who invited the other, the person with the highest social status, or the person asking for a favour. If you want to share the bill, then you must specify (and argue for!) going Dutch.

One of my students had some questions on this, so I looked it up in the BNC and COCA corpora. Actually, it seems that English speakers in the West never use "going Dutch" to describe the practice. As you say, there's no need to describe the default position. It's actually used as an metaphor and to make puns.

Dan Lufkin said,

September 4, 2012 @ 11:13 am

We should note somewhere that the French for "French leave" is filer à l'anglais.

Do not underestimate the sensitivity of government organizations to national slurs. I was once (late 80s) kept on the griddle for a couple of months on a charge of being anti-Uruguayan.

And there's also "Canadian doubles" in tennis (two females vs. one male).

And the "Chinese crosswind" is from "one wing low." The military would be sad to lose the expression "Chinese fire-drill."

Jonathan Mayhew said,

September 4, 2012 @ 11:26 am

It is deeply dishonest to say "Much has been written about whether these etymologies are spurious or not" when, in fact, much of what has been written has proven that they are spurious. It has the effect of perpetuating spurious assertions.

Of course, "the choice of wording affects our professional environment" is so vague that it would be impossible to object.

Barbara Phillips Long said,

September 4, 2012 @ 12:00 pm

The confusion between Dutch and "deutsch" is ongoing. When I was in junior high, the music teacher was lecturing us about Brahms, and wrote "Dutch symphony" on the blackboard as one of the composer's notable works. I didn't correct him, although I knew he was wrong. His remarks made it clear he thought the symphony honored those who lived in the Netherlands — it wasn't just a spelling error.

The terms like "Dutch treat" don't seem to carry much prejudicial freight when I've heard them, whereas when I was growing up, I did hear "jew down" and it was used in a vicious way. I've never heard "gyp" used with the same intonation that "jew down" had when I heard it, and that may be why I didn't associate it with gypsies.

Another term that carries derogatory freight is "Irish twins." The description "shanty Irish" is derogatory, too. I don't know whether "lace-curtain Irish" is also considered derogatory; it seems to be the opposite of shanty Irish, but I doubt either are flattering. The last two terms I've read in historical articles about the Irish, but I haven't heard the used in speech.

CuConnacht said,

September 4, 2012 @ 1:00 pm

@Barbara Phillips Long: Probably "Dutch Requiem", no? For "Ein Deutsches Requiem".

Nathan said,

September 4, 2012 @ 1:13 pm

@Allen: So if any clueless journalist or officious bureaucrat raises the issue, the idiom is automatically skunked?

Keith M Ellis said,

September 4, 2012 @ 1:15 pm

I'm astounded that Mark and LL commenters are arguing that etymology is determinative!

In my personal experience, about three times out of four when someone makes the arguments that are being made here — that an ostensibly offensive term isn't actually offensive and that arguing so brings disrepute onto all such arguments — the disputed term truly is offensive to a non-privileged group in ways that the privileged cannot see and consequently deny; and the worry about disrepute is a form of concern trolling.

Far more often than not, these rebuttal arguments are at best clueless, often tendentious (as this one is) and occasionally malicious.

Yes, folk etymologies are pernicious and often misused in prescriptivism; but the right response to this is to correct the false etymology and the false argument — that "proper" usage is determined by etymology as opposed to convention. It's not to argue for an alternative decision on acceptable usage as determined by the true etymology.

It's astonishing to me that Mark and others are holding the ramparts against the "crazies winning" given that this is the stereotypical prescriptivist peever response to similar arguments. The prescriptivist peevers say: "no matter what people commonly believe, there is an authoritative linguistic truth (etymological or constructive) that determines correct usage and were we to allow the mob to rule, madness would follow." Similarly, "handicap cannot be truly offensive because its etymology isn't offensive and those who argue that it is offensive, and appeal to a folk etymology to do so, are crazy people who are also ignorant and, by the way, are damaging the credibility and interests of the people they're concerned about. I have a dictionary and/or a background in linguistics and therefore I'm best able to determine what usage is and isn't offensive to 'handicapped' people!" If your first and strongest response is to ridicule other peoples' desire to avoid giving offense, then you should carefully consider why that is your first and strongest response.

What I would have expected from LL would be a response that is critical of the folk etymologies and the implicit prescriptivist rationale that such etymologies (true or folk) could be relevant while emphasizing that conventional usage is determinative (that is, if people are offended, a term is offensive, full-stop) and generally erring on the side of being sensitive to how language reinforces bigotry and inequality, and especially effectively so when it does in ways that are more subtle and not widely questioned. ("Who connects gyp with gypsies?" Well, the Roma do. That a given speaker doesn't, doesn't somehow make the term less offensive.)

What I certainly didn't expect is a time-warp to the early 90s and an Allan Bloom-esque rant against rampant PCism with an attendent sneer at the ignorance of the philistines.

Jerry Friedman said,

September 4, 2012 @ 1:47 pm

@Jeroen Mostert and Frans: Thanks for the information on Dutch customs. I wonder whether the customs were the same in the 19th century and "Dutch treat" had a basis in fact.

@M. R. Forrester: Wikipedia says (consistently with my slight experiences with émigrés) that in the Middle East, there's always a host at a restaurant dinner too, and any form of splitting the bill would be considered very rude.

There are 14 relevant hits on "go Dutch" at COCA (as well as 5 that are puns on the phrase, referring to such things as buying something Dutch, which shows that people expect the phrase to be known). Interestingly (to me), two of them are advice to women never to pay anything on the first date.

Maybe in some areas or social circles, the expectation is that each person pays their own, but I don't think that's true in general in the West, especially not on heterosexual dates.

Kate G said,

September 4, 2012 @ 1:50 pm

To clarify for those who say that a Dutch treat/oven/uncle is nice, my understanding is that Dutch or French in these context doesn't mean "unpleasant, nasty, messed up" etc (as Chinese firedrill does, or Chinese control in Hearts) but "not a". A Dutch uncle is not your uncle. A Dutch treat means neither of you is treating the other. Dutch courage isn't courage at all, it's being drunk. French toast isn't toast, it's fried. A French letter is not a letter and when you take French leave you were not given leave. Using these terms is still derogatory because it says that the French/Dutch/whoever do everything the opposite of "us".

I do try hard not to use any of these terms if I have a chance. There's no substitute name for French toast, but I get by without the others. I have been in a conversation where somebody used "Chinese control" and a friend of Chinese heritage objected. It's always hard to say "I am sure this phrase I like to use doesn't offend you."

GeorgeW said,

September 4, 2012 @ 1:55 pm

@Keith M Ellis: Without going back and carefully reading the OP and all the comments, I don't think that most, if any, here are arguing that "etymology is determinative." False etymology is just false and should not be accepted as a basis for proscribing expressions possibly involving nationalities or ethnicities.

If, IMO, a group thinks an expression is an insult or slur, I would not use it without regard to its etymology whether true or false.

L said,

September 4, 2012 @ 2:13 pm

I was once chided for using the expression "French drain." For those who don't know, this is a means for draining water from fields, lawns, and the like.

If Wikipedia is to be believed, they "were described and popularised by Henry Flagg French (1813–1885) a lawyer and Assistant U.S. Treasury Secretary from Concord, Massachusetts in his book Farm drainage."

I now call them Freedom drains, largely to free myself from having to make any sense at all.

Jeremy Wheeler said,

September 4, 2012 @ 2:48 pm

@ Keith M Ellis: Your comment highlights another issue that hasn't been discussed here: the extent to which extent causing offence is a valid reason to avoid saying something.

I take it as read that well-mannered people avoid deliberately offending but cannot subscribe to the view that avoiding offence is the primary reason behind amending our language. If it were then we would be at the mercy of whoever shouts "I'm offended!"

What is needed is a set of questions we might address to ourselves that are far more relevant to the situation of minority and disadvantaged groups. For example: to what extent is this language perpetuating negative stereotypes about the group in question and, thereby, perpetuating their oppression?

In the UK the argument against 'handicapped' (by those who take disability politics seriously) has nothing to do with causing offence. Rather, it is about where one situates the person in relation to his or her disability, i.e. are they intrinsically disabled or handicapped or is societal structures that disable. Simply avoiding words for fear of offending does nothing to change societal structures, and years of 'disability awareness' training containing large chunks about offensive language have made little difference to how disabled people are perceived and treated (though people are much politer when denying them access to services).

Keith M Ellis said,

September 4, 2012 @ 3:50 pm

@Jeremy Wheeler: I agree that there are more important things to worry about than language. There's a story I frequently tell (set in the early 90s when language PCism was arguably excessive in a way that I emphatically believe it is not excessive today) about a meeting I attended at a (large) university radio station just when the ADA passed in the US. The discussion centered exclusively on language usage — in some annoyance, I spoke up and suggested that the (well-regarded) news department might work on some stories concerning the university's compliance with the ADA and its plans to come into compliance (particularly with regard to physical access). There was a moment of silence, after which the discussion returned to language.

So, yes, I am strongly in agreement with the claim that addressing injustice should first focus on the practical.

But this isn't to say that langage usage doesn't matter. And language usage is especially relevant in the diplomatic, cross-cultural context where discussion and negotiation reigns supreme. It's particularly odd to me that the target here is a diplomat writing about considerations in diplomacy.

LL's bloggers and commenters are typically thoughtful about how various considerations intersect at issues such as this. I'm not seeing that in this post or thread. The usage of a false, folk etymology to rationalize a language usage proscription is unquestionably of interest and deserving criticism, but that is distinct from allowing a debunking of the folk etymology to serve as an argument against the proscription itself (especially in a constrained context such as diplomacy); and it seems particularly egregious to me to in any way to take a swipe at those inclined toward such considerations and especially to engage in what amounts to concern trolling. I don't believe it was by design concern trolling, but arguments of the form "being oversensitive about unimportant issue X just undermines your argument against the larger issue Y" is classic concern trolling and encountered in every single public discussion about the acceptability of arguably offensive language.

What we might be discussing is the existence of folk etymologies in general, and the sociology of this sort of folk etymology in particular. There are reasons why people look for, and are comforted by, arguments from etymology that rationalize their suspicion/distaste of a usage they believe is somehow objectively offensive to themselves or others. They are looking for a legitimacy they otherwise feel is lacking — and in no small part because popular notions about usage are prescriptive and not descriptive. It becomes especially important to point to an acknowledged authority and it's revealing that (in the case of a targeted group which does, or may, take offense) the group which takes offense is almost never considered authoritative themselves. But a dictionary is.

And the reverse is true, as well. While many false folk etymologies like that for "hold the fort" serve to legitimize their putative offensiveness, there are also false folk etymologies which serve to legitimize the claim that a usage lacks offensiveness. I promise that every single offensive term that most of us would believe are demonstrated as unambiguously offensive in their etymology have, somewhere, a folk etymology that argues otherwise and serves to justify its usage.

There are linguistic issues here — descriptivism versus prescriptivism; the prevalence and origination of false, folk etymologies; the sociolinguistics of offense and privilege — but this post and the discussion is largely a criticism of the particular rationale for proscription and is in service of a more general attack on such proscription in general as being ignorant, superfluous, and counter-productive. It's not really a linguistics discussion and, worse, it's a discussion that is in its politics aligned with those who make a habit of defending offensive speech.

I realize that in this I am overstating my case — the reality of this thread is more ambiguous. But it's striking to me that there's any ambiguity at all; I would have expected Mark and the discussion here to err unambiguously on the other side of the line.

L said,

September 4, 2012 @ 4:23 pm

Diplomats need to be especially clear about all of this, obviously. If you refer to a "Dutch [whatever]' then, aside from issues surrounding offense, a listener may not even recognize the expression as idiom and may instead assume that somehow the Netherlands are involved. That in turn could generate a misdirected set of ideas about what may well be an uninvolved third country. The US State Department, which corresponds to the Foreign Ministry in many other nations, is entirely correct in taking extra care about this, but it's a special concern applicable to international/multinational contexts.

It seems to me that Fox News, and we the readers, are extending this guidance into other contexts for which it was not intended. The guidelines for diplomatic speech are emphatically not the guidelines for everyday speech.

You can extend this principle to any profession or jargon. For example, in everyday life, few of us would spell Dutch as "Delta Uniform Tango Charlie Hotel" but the police or commercial pilots or many other special professions would never spell it otherwise.

How can I put this? Whiskey Tango Foxtrot.

Jerry Friedman said,

September 4, 2012 @ 5:21 pm

@M. R. Forrester: We got through my class material a little early today, so I polled my students on "go Dutch". Several students immediately volunteered that that was the term for a date when the man and woman pay their own shares. One woman somewhat assertively suggested "modern-day". When I asked for a show of hands for recognizing this sense "Dutch", to my suprise only 6 or 8 out of 20 native speakers raised their hands (though some others may not have been paying attention.

One student said he'd never heard such an expression. Another asked him what he would call it. The first student said he always pays, so he doesn't need a word. Whorf lives! (That is, Pop Whorf, named after Pop Warner.)

@L: Though it's probably especially wise for diplomats to avoid those expressions with "Dutch" to avoid misunderstandings, I don't see the possibility of similar misunderstandings with "hold [down] the fort", "rule of thumb", or "handicap"—except in so far as people speaking to L@ speakers might want to avoid non-compositional idioms.

Other Mike said,

September 4, 2012 @ 5:46 pm

@michael farris

Umm, I'm hoping you realize that that URL is for "nationallampoon.com", as in, the people that brought us Christmas Vacation.

J.W. Brewer said,

September 4, 2012 @ 7:55 pm

As has been suggested above (and as I assume would be obvious to the regular readership of the periodical in question), Mr. Robinson's function is not to advise our actual diplomats stationed overseas how to avoid giving inadvertent linguistic offense to those they deal with on behalf of our country. One hopes those giving that advice actually know what they're talking about, in a country-specific fashion, Rather, the office he oversees has an internal function, dealing with inter alia complaints by departmental employees that they have been mistreated by colleagues or superiors. http://www.state.gov/s/ocr/ In other words, he oversees the people who would for example need to deal with a hypothetical complaint that a female department employee was subjected to a discriminatory work environment by male colleagues as evidenced inter alia by the fact that they kept using the phrase "rule of thumb" in her hearing despite having been warned in an official Department publication that this might give offense. http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/biog/101624.htm is his bio, which indicates no prior State Department service (or formal training in linguistics) but considerable prior experience handling the same sort of function in other federal agencies such as the IRS as well as prior service as an administrator of some sort at Brown University, which was his undergraduate alma mater. I understand that LL's own Geoff Pullum is a visiting professor at Brown this semester, but I don't know that his role extends to reducing the propensity of alumni in public positions to disseminate questionable etymologies.

It is perhaps worth noting in terms of the politics of these things that Mr. Robinson has been a federal bureaucrat continuously since 1994 through both Democratic and Republican administrations and took on his current position at the State Department prior to the last election when Dr. Rice still was in charge and then has remained in that position during Mrs. Clinton's tenure. I don't know whether it's the sort of senior position (I forget the DC jargon) where Mrs. Clinton would have the absolute right to replace him with her own appointee if she so chose, or the sort of position held by career civil service types who are protected against being booted out without cause following a change in administration.

Barbara Phillips Long said,

September 4, 2012 @ 8:00 pm

@CuConnacht — The requiem is correct — thanks. I should have looked it up.

L said,

September 4, 2012 @ 8:38 pm

@JWBrewer – fair enough, but idioms are always dangerous around non-native speakers, and even between regions they can be misunderstood. It's plain from the postings above that offense is taken, justified or otherwise.

It may be absurd, over-sensitive, and frivolous – but even so an employer has sound reason to worry about it. Defending against even frivolous charges is costly. I don't know that worrying about loonies is, of itself, also loony.

Joe Green said,

September 4, 2012 @ 10:16 pm

@Keith M Ellis:

Really? Interesting. Examples please?

That's an ambitiously broad statement. Every single [demonstrated as unambiguously] offensive term?

H Klang said,

September 5, 2012 @ 3:05 am

Regarding "welsh", see the etymology of the word "Kauderwelsch" at http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kauderwelsch.

Kauderwelsch ist die abwertende Bezeichnung für eine verworrene Sprechweise, für ein unverständliches Gemisch aus mehreren Sprachen oder eine unverständliche fremde Sprache… Der zweite Wortbestandteil welsch ist eine alte deutsche Bezeichnung für die romanischen Sprachen und ihre Sprecher, die sich in geographischen Bezeichnungen wie Welschschweiz, Wallonien, Walachei oder Wales findet.

The history is rich, and the linguistic group under the most suspicion seems to be southern European travelling salesmen and not the residents of Wales.

Tracy W said,

September 5, 2012 @ 5:59 am

Keith M Ellis, it sounds all very good and well to avoid language that might be "truly … offensive to a non-privileged group in ways that the privileged cannot see and consequently deny", until you run into a situation where different members of a group have different takes on what is offensive.

In the course of my job, I frequently have reason to refer to the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland, in contexts that are likely to be read/heard by Americans and people for whom English is not their native language. While I am a Kiwi, I work with a number of people whom are British or Irish. (Perhaps I should say "and"). They are unable to agree on a non-offensive short term to refer to their geographical location that can carry suitable context as part of a wider discussion around Europe (Great Britain and Ireland is also acceptable but wordy,, the British Isles is not as it ignores the Irish, United Kingdom and Ireland implies that Northern Ireland is not part of "Ireland the geographical bit", to cover the main suggestions). Our documents are weighted down with footnotes explaining the ins and outs.

Now perhaps your answer for this is that that the British and the Irish are not non-privileged groups and thus it's cool to insult them. But being not non-privileged groups means that I can cite this case as an example of the ensuing difficulties of trying to avoid offending anyone, in the hope of focusing on that problem, rather than on my political attitudes. Being members of privileged groups also means that I can't just ignore their complaints either.

Another point is that members of non-privileged groups often disagree internally about whether words are offensive or not. See for example this linked evidence about Native American's attitudes to the term "Redskins". Just because a member of a non-privileged group tells you that something is offensive doesn't mean they're speaking for all or even a majority of the members of that group. And most of us don't have the time or money to conduct surveys whenever we're told a phrase is offensive.

chris y said,

September 5, 2012 @ 7:38 am

Is it more or less offensive to go Dutch if you take French leave to do so? And if you do, will your boss talk to you like a Dutch uncle?

As a couple of Dutch contributors said up-thread, these sorts of expression aren't offensive these days because the casus belli that gave rise to their being used in a derogatory sense are lost in the mists of time and these days Americans, Brits, French and Dutch generally rub along fine. But you might want to tread more carefully if the nationality/community named remains subject to hostility or discrimination.

chris y said,

September 5, 2012 @ 7:49 am

Mark F., as I understand it, in early modern English usage Germans were referred to as "High Dutch" (= Hochdeutsch), while Netherlanders were referred to as "Low Dutch"- high and low in this context being geographical expressions. At the time of Pennsylvania Dutch settlement this would still have been the case.

ThomasH said,

September 5, 2012 @ 9:50 am

While worrying about non-problems like the offensiveness of "going Dutch," which I've always thought of as a tribute to stereotypical thrift and practicality, here's one from the economists: Dutch Disease, the unfortunate effect on other exports if one export product, especially of a natural resource, becomes so spectacularly successful as to lower the exchange rate and make the rest unprofitable. Rightly or wrongly the "disease" was named for the Dutch in reference to the North Sea gas discoveries of the "60's.

Catanea said,

September 5, 2012 @ 10:15 am

@Kate G – The French for "French toast" is pain perdu, at least in the part of France I frequent; and my daughter enjoys translating that directly as "Lost Bread" when it's on our menu. If you're looking to avoid any possibility of offense.

Jonathan Mayhew said,

September 5, 2012 @ 10:43 am

I think that there is a difference between "rule of thumb" and "Dutch treat." Rule of thumb and similar expressions like picnic or hold down the fort are not offensive unless someone happens to have heard a spurious tale about their etymology. Any expression referring to a nationality directly has some possibility of giving offense, even if its etymology is not, in fact, offensive. If you allow people to outlaw innocuous expressions like "rule of thumb," then you do allow the ignorant and crazy to win. In other words, the argument to spurious etymology is the only justification for finding offense in the case of otherwise innocuous expressions.

Jonathan Mayhew said,

September 5, 2012 @ 10:44 am

… so the refutation must be the correct etymology.

Breffni said,

September 5, 2012 @ 11:03 am

Tracy W:

The problem lies in the assumption that there should be a short umbrella term for that pair of countries, or indeed any pair of countries. There isn't one for Germany plus Austria, or Belgium plus France, or Australia plus New Zealand, or even Spain plus Portugal (given that the Iberian Peninsula also contains Gibraltar). Supposing it was natural in your line of work to deal with any one of these pairs as, for your purposes, a unit. Would you say that 'they are unable to agree on a non-offensive short term to refer to their geographical location', attributing this to national sensitivities, or would you simply say, well, there doesn't happen to be such a term?

J.W. Brewer said,

September 5, 2012 @ 12:34 pm

Going back to the original post, the origin of "hold down the fort" seems obscure, other than that myl's research seems to show that it had not yet arisen when the Indian Wars were still in progress but rather developed as a purely metaphorical usage sometime in the mid 20th century. OTOH, presumably the various American journalists among whom it first gained currency had seen plenty of Western movies with fictional forts being besieged by fictional Indians. It's not crazy to hypothesize (although I don't know how you'd come up with evidence to prove or disprove) that to the extent they had a paradigm mental picture of a literal fort-being-held-down underlying the metaphor it might well have been derived from such movies. (Is it too stereotypical to think that the journalists from the early cites were more likely to have been moviegoers than hymnsingers?) I don't personally find that just-so story I just crafted to make the phrase "offensive," but who knows what others might think?

Tracy W said,

September 5, 2012 @ 2:50 pm

Breffni: