Blue Cell Dyslexia

« previous post | next post »

An article about dyslexia appeared last week in the prestigious Proceedings of the Royal Society B (“The [British] Royal Society's flagship biological research journal, dedicated to the fast publication and worldwide dissemination of high-quality research”). A week is a long time in blog-years, I know, but impact of the article is rippling far and wide. The authors claim to have identified a visual basis for dyslexia: an anomaly involving the distribution of a type of receptor in a part of the retina. This anomaly may provide “the biological and anatomical basis of reading and spelling disabilities”, with “important implications in both fundamental and biomedical sciences.” They also seemed to demonstrate that the anomaly could be easily eliminated by changing lighting conditions.

As might be expected, the media picked this up as scientists maybe having at long last found the cause of dyslexia.

Dyslexics, their families and teachers, reading researchers and treatment specialists, and the organizations that represent them are asking: did someone just discover the cause and cure for dyslexia? (I know this: I get email.) As someone who has conducted research in the area, my question is different: how did this terrible article get published and how can its harmful impact be counteracted?

Nothing whatever can be concluded about the causes of dyslexia from this study, as it is described in the article. Basic information about the methods and results are not provided; the procedures used in collecting the data raise numerous concerns; the link between the purported anomaly and dyslexia is conjectural; and the impairment does not explain other, better established facts about reading impairment. The study is based on some of the hoariest stereotypes about dyslexia—that it results from reading letters backwards and/or pathological persistence of visual images, that can be corrected by manipulations that affect color perception.

At first I was hesitant to evaluate the study because I’m not a vision scientist, but then I realized that hadn’t prevented the authors from publishing it. Albert Le Floch and Guy Ropars are affiliated with the Université de Rennes, France. Their primary area of expertise appears to be laser physics. The study does deal with some obscure aspects of the visual system that are well outside my expertise so caveat emptor, but the problems with the study are far more basic.

Here’s what they report, in brief.

Sixty college students participated in the study, 30 normal readers and 30 dyslexics, described as individuals with “reading performance significantly poorer than expected.” That is all that is known about their reading. A competent study would normally include descriptive data about the subjects in the two groups to establish the validity of comparisons between them, e.g. age, handedness, language background, a measure of nonverbal IQ, measures of spoken language such as vocabulary and comprehension. Then there would be assessments of their reading skills and performance on related tasks on which dyslexics are typically impaired in order to establish that people who self-report as struggling readers exhibit characteristic dyslexic behaviors. These tasks would include things like reading words and nonwords aloud, judging which of two stimuli is the correct spelling of a word (e.g., RAIN RANE), speed and accuracy of naming letters, colors, objects (the Rapid Automatized Naming task), and others. In French, which has more consistent spelling-sound correspondences than English, dyslexics would be expected to read words and nonwords aloud accurately but slowly, with a bigger impact of word length than in English.

The discussion could stop here because it’s not known if the subjects were dyslexic or if the two groups differed in other ways.

The account of the visual deficit has three parts.

1. Atypical ocular dominance in dyslexia: The researchers examined ocular dominance, the greater reliance on input from one eye compared to the other, using a standard test and a new one they devised that relied on visual afterimages. The nondyslexics showed asymmetrical dominance (some right, some left) on both tests: 28/30 on the standard one, 30/30 on their new one. Fewer dyslexics showed this asymmetry, 16/30 on the standard test and only 3/30 on their new one. Thus 27/30 dyslexics were said to show an atypical symmetry in ocular dominance as determined by visual afterimages.

2.Retinal anomaly in dyslexia: The researchers report a corresponding pattern concerning the distribution of a type of retinal cell. The retina contains short (S), medium (M), and long (L) cones, the labels referring the wavelengths to which they are most responsive. The authors refer to them as blue, green, and red cells, respectively, but the cells are not specifically tuned to those colors. I’ll follow their terminology.

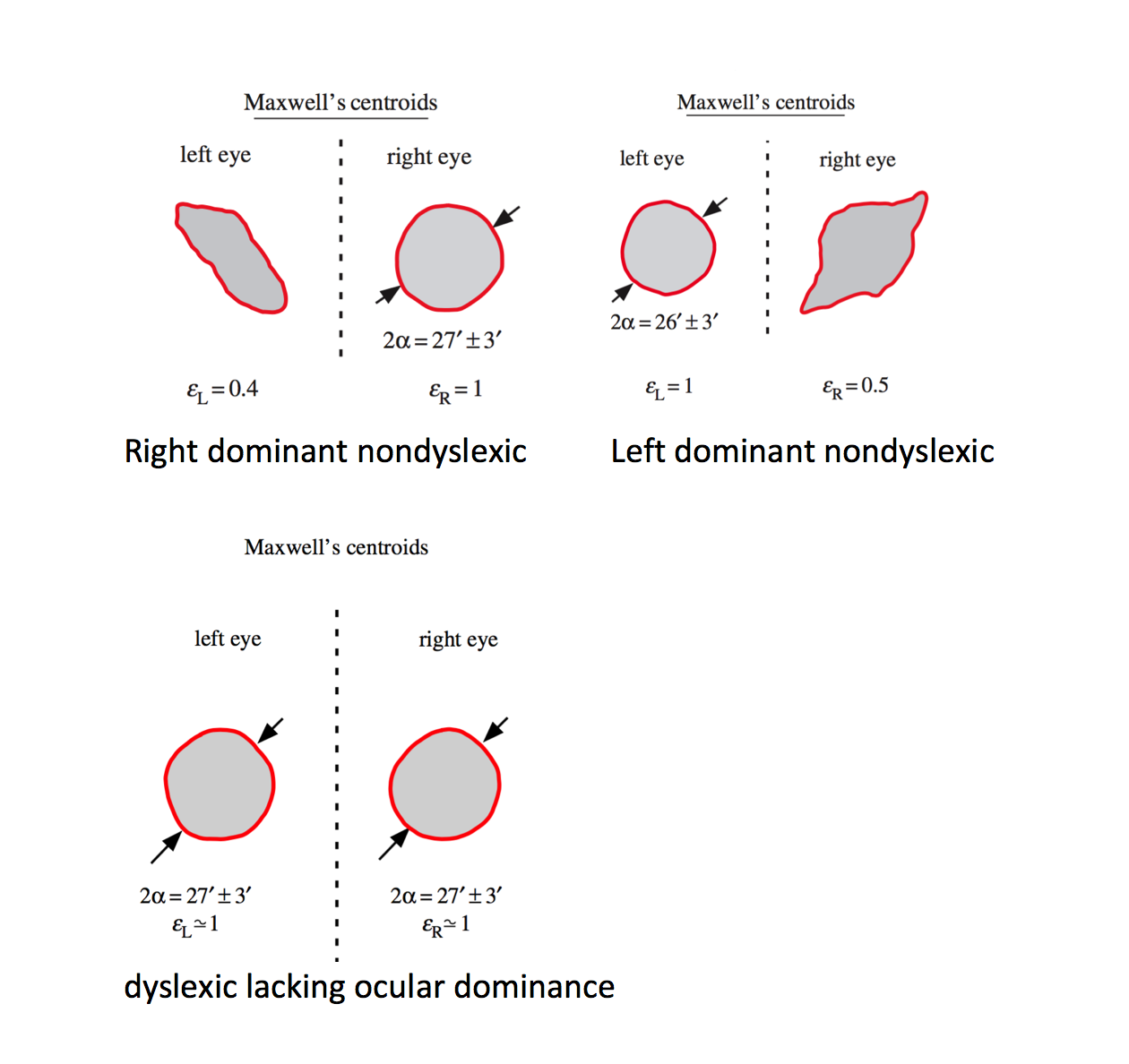

Blue cones are not found in a part of the fovea (the central part of the retina where acuity is highest) known as Maxwell’s spot. The researchers estimated the size of this area in each eye in each subject. For all nondyslexics, the region was bigger in the dominant eye. For the 27/30 dyslexics who didn’t show the dominance asymmetry, the size of this blue-free area exhibited a corresponding lack of asymmetry. The shapes of the areas from two nondyslexics and one dyslexic were illustrated:

Ocular dominance, they conclude, is determined by the relative sizes of the Maxwell spot. The spot is atypically symmetrical in dyslexia, producing the atypical lack of ocular dominance.

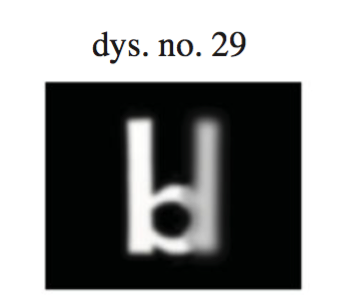

3.Impact on reading. These anomalies are then used to explain why dyslexics perceive letters such as b and d incorrectly. The lack of ocular dominance causes the dyslexic to perceive both the letter and its mirror image. Moreover, the persistence of the images can cause the two to be perceived simultaneously, as in this illustration:

They then report that the extra, mirror-image letter can be suppressed by changing the lighting of the stimuli.

This is not good.

- The claims about dyslexia— that it is strongly associated with atypical ocular dominance, that dyslexics have atypically long visual persistence, and that they misperceive mirror-image letters such as b and d— have been studied for decades and discredited. It is a big literature and some studies show such effects in some subjects, but most do not. The authors write as though these are established but unexplained characteristics of dyslexia, which is wrong.

- On the vision side, the authors claim that the bases of ocular dominance are poorly understood, but again seem unaware of extensive research on the topic. The authors observed a correlation between ocular dominance and the shapes of the Maxwell spot and concluded the latter causes the former. There’s no explicit theoretical link between the two, making this a textbook example of mistaking a correlation for a causal relation.

- There’s no theory of why differences in the distribution of blue cells would have any impact on any aspect of reading under normal conditions. (I would have had subjects read texts printed in blue, red, and green and seen if it had any impact whatsoever.)

- The critical data about the Maxwell area are highly suspect. The authors did not count cells on subjects’ retinas; they used an indirect method. The absence of blue cells in this part of the fovea—which is normal—is undetectable in real life. Under laboratory conditions employing colored filters and elaborate lighting conditions, this area produces an entopic image—one that is produced by the retinal cells rather than an external image. The size of the Maxwell area was estimated by having the subject draw an outline around the entopic image, as they experienced it, on a pad computer, which was simultaneously projected on a screen. Although it’s hard to tell from the description (p. 2), the experience seems to have been similar to outlining an actual image on a screen.

Subjects’ accuracy in drawing such images is unknown, as is the relation between the images and actual properties of the retina. Control conditions in which subjects’ accuracy in tracing other shapes weren’t included.

- The study provides no systematic evidence about the perception of mirror-image letters or the superposition of two letters. The phenomena are illustrated by a few examples taken from 5 of the dyslexics. The figures illustrating these phenomena are “reconstructed afterimages” based on subjects’ reports of what they saw. How often these experiences occurred in dyslexics and nondyslexics isn’t reported, just examples.

This study is a failure in three respects:

As a study of dyslexia. They’ve reported findings that are inconsistent with many other studies over a many year period. Dyslexia is not a backward letter or visual persistence disorder. The alphabet doesn’t even HAVE many mirror image letters, which is an effective way to obviate the problem. Reversal errors are sometimes made and they can be elicited under artificial conditions, but the causes are not necessarily found in early vision. See the very interesting study by Treiman et al., who found that errors are more frequent on leftward facing letters like d and q compared to their rightward facing partners. Most letters in the Latin alphabet are rightward facing; the errors are then attributable to this statistical regularity, not the mirror image property.

In 2017 it’s not sufficient to do a study of a small number of dyslexics, find some way in which they differ from nondyslexics, and claim to have found the cause or even a cause of dyslexia. It’s necessary to connect to previous research and to address conflicting findings. It is also hard to determine cause and effect from studies of adult dyslexics who have lived with the condition a long time.

As a study of the visual system. Tasks like the ones used here are subject to external influence, and the fact that the researchers do not report having ensured that the individuals collecting the data were blind to the subject’s reading status is a cause for concern. The theory linking blue cells to ocular dominance and image persistence is vague; vision experts can weigh in on whether there is any connection. Their new method for assessing ocular dominance yielded different results than a standard test, possibly because it was based on visual persistence—which they claim is anomalous in dyslexia.

As a behavioral experiment. Lack of basic information about subjects, lack of behavioral evidence of dyslexia, lack of any measurements of reading skill, incomplete presentation of data, etc. I think that many casual readers of this dense, poorly written article will be deeply misled by figures such as the superimposed letters above. Those are reconstructed images based on subjects’ self-reports. In a famous study, researchers reconstructed letters and symbols that subjects were viewing from fMRI signals. Here’s an example from their paper. The top row shows the actual stimuli (presented on different trials), the other rows show the image as recovered from the brain data. The images look similar to the one above, but they are generated by wholly different methods.

Final comments: we know a lot about dyslexia but not enough. It’s very clear, however, that there isn’t a single cause and won’t ever be one. The condition arises from a confluence of underlying causes that vary in severity producing a range of behaviors—a dyslexic spectrum. The challenge isn’t to find the single cause for dyslexia but to understand how these underlying conditions conspire to produce the disorder.

The study of visual deficits in dyslexia has a long, difficult history. The natural assumption is that the disorder must arise from a defect related to what’s unique about reading, the visual code. Whereas it has been hard to find consistent evidence for visual impairments, there is a huge body of evidence about the role of impairments in spoken language. The challenge for any visual deficit theory is to explain, for example, the results from prospective longitudinal studies of children at risk for dyslexia showing that the reading problem is preceded by impairments in processing speech within the first 36 hours of birth, and later by deficits in phonology, vocabulary, syntax, and other components of spoken language. I discuss these studies in my book.

Of course anomalies in the visual system probably are among the contributing causes in some unknown percentage of cases. Hey, I’m a co-author with Manis, Sperling, and Lu on four articles that yielded such evidence (they're here), and on one in which dyslexics were superior at processing some types of visual images. Researchers are still discovering basic facts about the structure and function of the visual system, not to mention language and the rest of the brain. There are multiple anomalies associated with dyslexia and the problem is to see how they fit together. That will require large-scale studies in which researchers examine multiple deficits in the same subjects, rather than focusing on their pet theory. It will also require competent studies that build on previous research and relate to existing findings.

How did the paper get published? Can’t say. The probability of successfully getting through the review process might be higher at this journal, which is aimed at biologists and has no one on the editorial board who is an expert in dyslexia. We know that many educators still believe neuromyths about dyslexia and cognition such as the backward letter meme, including people with a neuroscience background. The probability would be far lower at a specialist journal such as Scientific Studies of Reading.

h/ts Will Graves (Rutgers), John Henderson (UC Davis)

Coby Lubliner said,

October 27, 2017 @ 8:19 am

In French, which has more consistent spelling-sound correspondences than English

I would question that. Just think of the ways of spelling word-final /o/.

Darryl Shpak said,

October 27, 2017 @ 8:36 am

"In a famous study, researchers reconstructed letters and symbols that subjects were viewing from fMRI signals. Here’s an example from their paper."

Is the link to this "famous study" pointing to the wrong place? It takes me to a paper titled "Ocular dominance, reading, and spelling ability in schoolchildren", which is interesting and relevant but has nothing to do with image reconstruction from fMRIs.

[MSS: Yes, it was a cut-and-paste error. Link has been corrected.]

Rodger C said,

October 27, 2017 @ 9:55 am

@Coby Lubliner: Spelling-sound correspondences, not sound-spelling correspondences.

Adrian said,

October 27, 2017 @ 11:52 am

The odds were lower, not higher.

Mark Seidenberg said,

October 27, 2017 @ 11:57 am

[MSS: corrected, thanks]

Jerry Friedman said,

October 27, 2017 @ 12:20 pm

As a physics teacher, I looked at the famous study's image that says "neuron" and saw "newton". I believe this is a condition called physlexia.

Allan Freedman said,

October 27, 2017 @ 1:10 pm

Thank you for this. As a dyslexic and a parent of a profoundly dyslexic son I have struggled to identify and avoid smoke and mirror "cures" for dyslexia. While there is a lot of exciting research on the subject of dyslexia, this paper is a huge injustice to the approximately 13% of the population with dyslexia. Sadly it will be used by parents looking for an easy fix and worse, by eye doctors who want to sell their vision therapy services. They will hide behind this "research" and its ilk to peddle their expensive "fix" for dyslexia. Parents, desperate for a solution, will seek anything dressed up with a respectable veneer and pour potentially large dollars into this useless abyss (unless the child has real vision problems separate from dyslexia). For me, this is every bit as evil as that British doctor, Andrew Wakefield, who fraudulently connected vaccines to autism.

Wendy Milanese said,

October 27, 2017 @ 4:09 pm

Lots of fake news going on these days so I assumed someone threw in this fake study too. I actually was waiting for a punch line at the end. Thank you for following up to set the record straight. Dyslexia is the result of a language disorder, my daughter was diagnosed with central auditory processing disorder, and expressive/receptive language disorder. This child at only 5-6 years of age, described how the words ran off the page and all ran together. For her, there was no putting the sound to the letter but she could read music and play a piano. It's a different part of the brain. Struggling readers need to Follow an intensive multi-sensory approach to reading plan and don't give up. It won't take long before you start to notice improvements in reading.

AntC said,

October 27, 2017 @ 5:08 pm

@Wendy … Dyslexia is the result of a language disorder, my daughter …

I think Mark's article is cautioning that dyslexia is complex; not "the result of" any one thing in particular; and therefore not susceptible of an easy 'fix' — as the paper (or at least the media treatment) appears to claim.

My sister's dyslexia seems quite different to your daughter's. My sister has always been very orally articulate, and succeeded in masking her dyslexia for many years through the school system. She was therefore diagnosed too late; and struggled when she could no longer learn by listening/speaking.

AntC said,

October 27, 2017 @ 5:19 pm

Are there comparative studies of dyslexia in different writing systems? wikipedia has a little on different Latin-based languages: English/French have 'deep' phonemic orthographies compared to Spanish/Italian.

Does dyslexia in right-to-left languages have different characteristics? (I'm thinking about right-facing vs left-facing letters; in which case Arabic script seems very different compared to Hebrew.) Also I believe dyslexia can be associated with not having strong handedness. Left-handed writers always seem to struggle writing left-to-right languages. (And I have contemporaries who got punished for being unable to write right-handed — bloody nuns!)

Tina Engberg said,

October 27, 2017 @ 6:39 pm

What Allan Freedman said. I told someone that this was equivalent to potential damage to those of us trying to get help for our dyslexic children as the Wakefield fiasco. That person (also a parent of a dyslexic) went off on me about the Wakefield thing. I get it. People want an easy way out of helping dyslexic children, and sensational headlines push the message to people who otherwise wouldn't care one iota. Thank you for your analysis, Dr. Seidenberg. You're a rock star!

Sara Peden said,

October 28, 2017 @ 12:23 am

Fantastic analysis. Thanks so much for doing all that work! I only got as far as the freely available abstract. Some might be interested in seeing my analysis the day the newspaper articles were drawn to my attention to get an idea of how to evaluate without even getting to the study itself. I hope people will take a look. Dr. Seidenberg … would be interested to know if I was off base on anything (from someone who has actually read the article).

https://www.sarapeden.com/blog/2017/10/20/a-cure-for-dylsexia-really

Francesco Rocchi said,

October 28, 2017 @ 12:23 am

My first thought when I read the article (which I nonetheless believed to, as I am no expert) was that, if the problem was just a matter of anomalous symmetry, dyslexic people should just close an eye while reading, and voilà.

Abigail Marshall said,

October 28, 2017 @ 6:47 am

J'accord.

My take: https://blog.dyslexia.com/visual-dyslexia-new-study/

mg said,

October 28, 2017 @ 2:55 pm

Sadly, as journals and pressure to publish have proliferated, so have bad science articles that make it through peer review. As a methodologist, I've been stunned at the dreck that makes it to print in supposedly reputable journals. One of the worst is The Lancet, which has been known to ignore peer reviewers in order to gain media attention (worst example – the unforgivable publishing of Wakefield's harmful crap about vaccination causing autism).

In my not-so-humble experience, every scientific journal should have a statistician/methodologist on staff to vet articles before acceptance (but money). It should go without saying that they should make sure a subject-matter expert is one of the reviewers (as Mark said, review by a dyslexia expert would have caught errors). Unfortunately, that is easier said than done, since peer-review is unpaid service and doing it well is time-consuming.

tangent said,

October 28, 2017 @ 3:34 pm

Why on earth would the two eyes perceive mirror images?

Margaret Wilson said,

October 28, 2017 @ 6:59 pm

mg: There is also, more specifically, a trend of biology journals pushing into behavioral science topics. They tap biologists for their reviewers, who are like babes in the woods when it comes to this stuff. Current Biology is particularly guilty in recent years.

David Ayer said,

October 29, 2017 @ 3:16 am

If no one can afford to have such an article peer reviewed, how can we expect mainstream magazines to wrangle subject knowledge and delve into the weeds, instead of simply Xeroxing them with misleading headlines. But somewhere in there a lot of damage is being done in the wider world.

AntC said,

October 29, 2017 @ 4:36 am

@ a tangent Why on earth would the two eyes perceive mirror images?

Indeed. Something to do with left-brain, right-brain?: I remember attending a 'Presentation Skills' course in which it was alleged you should have two projection screens. To the right with pictures — right eye -> left-brain; to the left with text/numbers — left eye -> right-brain. Or very possibly the other way round — I can't remember either the picture or the text that was supposed to explain it.

Since the screens were to be several metres apart, but my eyes only a couple of inches, I was bemused how I was to stop both eyes looking to the same place at the same time.

But apparently some Industrial Psychologist had done an experiment. With about as much validity as our pair of laser physicists, I suspect.

Abigail Marshall said,

October 29, 2017 @ 5:56 am

Perception is primarily a mental process – the eyes take in information, but the brain interprets, fills in, reconciles… and often makes mistakes. A letter reversal is just one sort of perceptual error the brain can make– similar to the comment above about seeing "newton" rather than "neuron". Good article here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1079232/

If you can confuse someone enough, they will "see" all sorts of things that aren't there (or completely miss seeing things that are there). Plenty of studies on that, generally in psych or cognitive science labs. An early experiment in that realm was the 1949 Bruner & Postman study – "On the Perception of Incongruity" – here: http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Bruner/Cards/

Obviously if someone creates an exercise that is disorienting enough to induce sensory confusion, then no possible conclusions can be made related to the function of the eyes; the researchers have essentially poisoned their own well.

David Hilbert said,

October 31, 2017 @ 2:00 pm

Regarding criticism 3. I don't think they intend any claim that the spectral characteristics of the cones themselves affect reading performance. Rather, the S-cone distribution is the technique they use to identify the foveola (area of highest cone density) and it is the characteristics of this region that they claim is relevant to dyslexia.

I would definitely want to see some validation of their imaginative technique for identifying the location and shape of an area of high cone density. A striking absence from their discussion is any apparent awareness of the enormous increase in the knowledge of the features of the cone mosaic due to the introduction of adaptive optics to directly image the cone mosaic starting in the late 1990s. Their indirect method of measuring one aspect of the cone mosaic is fast and cheap but it's hard to know exactly what's being measured without some comparison to the results of direct imaging which is definitely possible.

Gregory Morrow said,

November 2, 2017 @ 12:58 pm

It is a well-known phenomenon that physicists (being the arrogate masters of the scientific universe that we are), especially emeriti, often parachute into unrelated fields and assume that we can cut through all of the mysteries in the field by making gross simplifications and ignoring all the hard work that has gone before in demonstrating that the gross simplifications don't work.

I stopped assuming that the paper had any validity when Dr. Seidenburg reported that the authors were laser physicists. I know my tribe.

[(myl) Indeed — see "The life cycle of physicists", 3/21/2012.]

Smut Clyde said,

November 3, 2017 @ 2:22 am

The lack of ocular dominance causes the dyslexic to perceive both the letter and its mirror image.

That. makes. no. sense. (as Tangent and AntC have already said).

May I recommend the invaluable services of PubPeer?