Google me with a fire spoon

« previous post | next post »

Despite its simple and straightforward Chinese vocabulary, this sign in Dalian (a large city in northeast China) is badly translated into English:

(As usual, you may click on the photograph to embiggen it.)

The problem seems to be that the syntax and semantics present challenges that far exceeded the grasp of the translator, resulting in complete gibberish in many cases. This is especially true for the parts of the sign where there are whole sentences and where classical / literary grammar intrudes upon the Mandarin.

tiānxià míng bǐng 天下名餅 ("world famous flat cake")

translation on sign: World famous cake

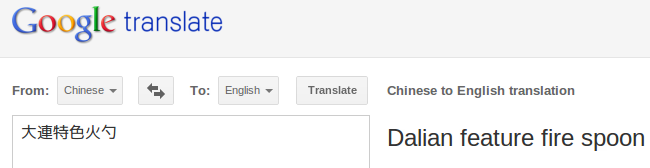

Dàlián tèsè huǒsháo 大連特色火勺 ("Dalian style baked flat cake")

translation on sign: Dalian feature fire spoon

xiāngtián kěkǒu 香甜可口 ("sweet and delicious")

translation on sign: Sweet and delicious

ruǎnyìng shìzhòng 軟硬適中 ("al dente")

translation on sign: Moderate hardness

lǎoshào jiē yi 老少皆宜 ("suitable for young and old alike")

translation on sign: Ages

huíwèi wúqióng 回味無窮 ("savor endlessly")

translation on sign: Food for thought

Bù chī bù zhīdào 不吃不知道 ("If you don't try one you'll never know")

translation on sign: Do not eat do not know

Chīle wàng bù diào 吃了忘不掉 ("If you try one you'll never forget it")

translation on sign: Eat forget

Chīle hái xiǎng chī 吃了還想吃 ("Once you eat one you'll want to eat more")

translation on sign: Still want to eat eat

Dì yīcì búmǎi yuàn nǐ 第一次不買怨你 ("If you don't buy one the first time, blame yourself")

translation on sign: Do not blame you first buy

Dì èr cì búmǎi yuàn wǒ 第二次不買怨我 ("If you don't buy one the second time, blame me")

translation on sign: Blame me not to buy second

Problematic English translations on signs in China are hardly news — but in this case there's a new twist. Every one of the translations on that sign is word-for-word what Google Translate now gives. Here are a few examples.

This should be something like "Dalian style baked flat cake":

This one should be something like "suitable for young and old alike":

And similarly, here are screenshots of Google Translate coping with phrases that should be rendered as "If you try one, you'll never forget it", "If you don't buy one the first time, blame yourself", and "If you don't buy one the second time, blame me". (The syntax and semantics of the last pair of cases is especially interesting, and deserves a post of its own.)

Apparently Chinese sign-translators are realizing that today's Google Translate is a big step up from the systems that some of them have used in the past — but blind faith in machine translation is still creating little gems of aleatoric poetry.

Aside from all of the other gaffes, large and small, the most serious lexical problem is what to do with huǒsháo 火勺. Literally, the two characters do mean "fire spoon," but that doesn't make any sense in the context where the term appears. Some native (but non-local) readers of the sign suspect that huǒsháo 火勺 must be a miswriting for huǒshāo 火燒, which does indeed signify a type of flat cake, though it is usually said to be fried in a pan, unlike huǒsháo 火勺, which is baked in an oven.

Others, however, contend that huǒsháo 火勺 is simply the way people from the northeast (where Dalian is located) refer to huǒshāo 火燒.

Be that as it may, both huǒshāo 火燒 and huǒsháo 火勺 are flat cakes with filling. Moreover, the two forms are obviously near homophones in Modern Standard Mandarin (MSM).

In Dalian topolect, however, shāo 燒 and sháo 勺 have different tones than they do in MSM. There are three tones in the topolect, with tone2 having split and merged with either tone1 or tone4 (for example, yáng 羊 ["sheep; goat"] is tone1, and yáng 洋 ["ocean; foreign"] is tone4 in Dalian topolect). MSM shāo 燒 is tone1, and MSM sháo 勺 is tone4. For the word "huo3shao0", the second syllable is tone0 in Dalian topolect. This is yet another example of phonology and semantics winning out over sinographic orthography.

[A tip of the hat to Xiang Li, and thanks to Rebecca Fu, Jiahong Yuan, and Ying Zhou]

joe said,

July 28, 2011 @ 5:58 am

when i read the first few sentences of the blog, i began to suspect that the translations might have come from google machine translation or baidu machine translation. i am not sure, but it may not be the blind faith in google or any other machine translation. it's partly because many business people in china are unwilling to pay for translations and partly because most people who know little english have no idea about quality of the translation you get from google free of charge.

it is a fact that some publishers pay impossibly low wages for translations. that is probably why there are so many poorly translated books flooding the market. it is the unwillingness to pay for trustworthy translation services that leads some people to choose machine translation. and most of these people don't care whether the result is good or not. and they are not in a position to judge the quality of any translation they get.

a few years ago i was asked to proofread a thick brochure translated into english from chinese. the whole thing was poorly translated, but i was flabbergasted to find one paragraph especially abominably translated. i scratched my head wondering why it was so bad. i got an idea. i put the chinese paragraph to the google translation and got the exact result that had puzzled and flabbergasted me. well, the thing had been done by a translator. proofreading was given up. i did the job again from cover to cover.

probably this translator and many other similar translators are reasons why some publishers have long since lost faith in translators and why some customers turn to google translation service. a vicious cycle.

David Moser said,

July 28, 2011 @ 7:27 am

Wonderful stuff, I love this.

Makes me muse again about the appeal of bad translations like this. Isn't the giddy joy of Chinglish, in part, this: It isolates the same problems and glitches that EVERY SINGLE TRANSLATION in history, even the best, are afflicted with, and magnifies them many fold. Even the translations I'm most proud of have phrases and passages that make me cringe later on. Examples like this sign enable us to study such semantic mishaps in extremis.

Plegmund said,

July 28, 2011 @ 8:17 am

Language Log: sweet and delicious; moderate hardness; food for thought.

Rob P. said,

July 28, 2011 @ 9:49 am

What happened to the option on Google Translate to "submit a better translation"?

Kaiser said,

July 28, 2011 @ 10:31 am

In my reading of this, one particular translation stands out: 老少皆宜 to "Ages". In the other examples, you can see character-for-word translations but instead of a direct character translation, Google recognizes correctly the topic of the phrase.

Anyone can speculate how Google Translate's algorithm manages to come up with "Ages"?

Mark said,

July 28, 2011 @ 12:35 pm

@Kaiser, I can see that phrase being used in documents in a way that would translate into English as "all ages". It is only a single machine miss-step away from dropping the "all" part because it matched some other partial phrase.

YT said,

July 28, 2011 @ 10:02 pm

I think this is also an example of bad design for a sign in Chinese and English. Switching between vertical and horizontal Chinese characters is reasonable. Add vertical and horizontal English letters and I'm now slightly dizzy.

Kaiser said,

July 29, 2011 @ 9:13 am

@Mark: I see what you mean. Ironically, a direct character-to-word translation would have conveyed the meaning much better.

One other issue I noticed about the translation is that it loses the paragraph structure. The two sets of sentences on the right belong together and should be translated as a block. This is especially true of the rightmost sentences, any decent translation should use a common sentence structure for each sentence! (I tried entering both sentences into Google Translate; it's not sophisticated yet to make the association.)

The Stupidest Most Intriguing Restaurant Sign, Complicated yet Compelling | stupidest.com said,

July 29, 2011 @ 9:17 am

[…] language log […]

Hermann Burchard said,

July 29, 2011 @ 5:32 pm

吃了忘不掉 ("If you try one you'll never forget it")

[Italicized Chinese glyphs!!]

If you put spaces, Google changes translatiions but stil seems to get it wrong:

吃 了 忘 不 掉 –> Do not forget to eat out

More drama when separating by commas, hyphens, or tildas . . .

(From a non-Mandarin ignoramus)

Victor Mair said,

July 29, 2011 @ 8:16 pm

From Xiang Li:

Here are some pictures of what a huǒsháo 火勺 looks like. Apparently, Yanqing 延庆 (a subdivision of Beijing municipality, to the northwest of the city proper) also claims these to be their specialty.

http://www.dianping.com/group/yanqing/topic/982769

History of huǒsháo 火勺: http://baike.baidu.com/view/1819619.htm

mary said,

July 30, 2011 @ 8:53 am

I was just in Beijing; do not speak Mandarin but noticed a hair salon with the name, in English: Beauty 5 All. Taking it up a notch!

Sai said,

July 30, 2011 @ 7:09 pm

I thought 'food for thought' a pretty interesting translation although the idiomatic play on words (ideas?) was probably unintentional on the part of the translator.

Ying Zhou said,

July 31, 2011 @ 10:40 pm

I searched the item "火勺' and found the following information: 火勺, 即火烧,一般东北人习惯将火烧叫成“火勺”。I also learned that 火勺 mainly refers to the baked cake with the fillings of ground beef. (牛肉馅饼). There is another type of sticky flat ones made of sticky rice, which are called 粘火勺. In many areas of Liaoning province, people habitually pronounce the first-tone characters(in Putonghua) as the the second tone. For example, I often pronounce the number 3 as san2 instead of san1. I suspect that this is the reason why 火烧 is mixed with 火勺, because several Dongbei areas such as Tieling and Yanji claim that huoshao are their famous local food.

In this case, maybe "fire cooked" is a better translation for the food. But I like both the Chinese version of 火勺 and its English counterpart of "fire spoon", which, for me, contains some sense of humor. :)

LareinaFireSpoon said,

August 2, 2011 @ 3:14 pm

WOW…this ad is funny!

Actually – fire spoon was originally from Beijing, which was called Donkey Meat Fire Spoon (驴肉火烧)

but obviously they need a better translator!

Starr said,

August 2, 2011 @ 4:42 pm

A few days ago a classmate of mine had the exact same Google Translate issue with the 不 A 不 B (if not A then not B) pattern. He posted a Facebook status update in Chinese about how he was enjoying a particular class, but due to his use of the above pattern, the Google Translate English version made it appear that he was calling the professor terrible!

On the bright side, due to the way Google Translate works, it has more success with this pattern in well-known phrases. For example, 没有共产党就没有新中国 translates successfully as "would be no new China without the Communist Party," but it fails when those nouns are replaced with novel items, like "没有美国就没有摇滚乐", which Google translates as "not the United States did not rock".

Dalian dialect and tone… we’ll optimistically call this Part 1 « The (Y)east Also Rises said,

August 26, 2011 @ 8:09 am

[…] 2011 Better late than never, I decided to attempt to pursue the no-longer-so recent statements on Language Log about Dalian dialect (or topolect, as Victor Mair, the author of the post, more accurately calls […]

Engrish Me Once, Shame on You. Engrish Me Twice… « WTFUX said,

September 14, 2011 @ 2:24 am

[…] languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu Share this […]