Quadrilingual Garbage

« previous post | next post »

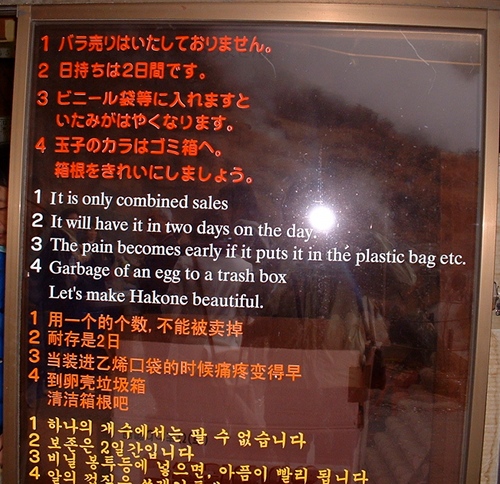

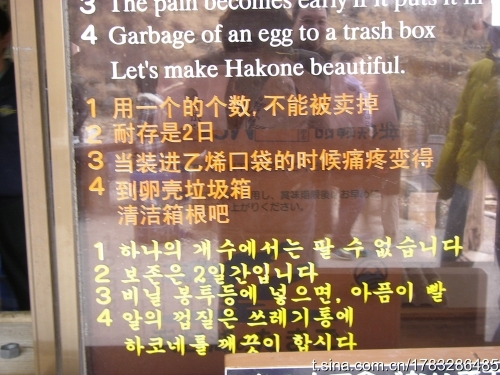

This notice on the window of a shop selling a very special type of life-extending egg in Hakone, Japan vies for the worst signage translation we've ever seen.

I've had to patch the sign together from two sources on the Web, neither of which is complete in itself. The top part comes from a remarkable blog ("The Dynamic Duo") maintained by a pair of brothers, one of whom lives in Idaho and the other in Japan. The bottom portion comes from a Sina microblog.

|

|

The English, Chinese, and Korean translations are all close to being gibberish. To see what was intended, it is necessary first to provide an accurate English rendering of the original Japanese:

1.バラ売りはいたしておりめせん。

2.日持ちは2日間てす。

3.ビニール袋等に入れますといたみがはやくなります。

4.玉子のカラはゴミ箱へ。

箱根をきれいにしまょう。

1. [We] do not sell [eggs] separately / individually.

2. [The eggs] will keep for two days.

3. They will quickly spoil if placed in a plastic bag, etc.

4. [Dispose of] the egg shells in a trash can. Let’s keep Hakone clean / beautiful!

The word itami いたみ (itamu いたむ) in the third line means “to go rotten / spoil.” The fact that its most common meaning is “pain” causes all three of the translations to grossly misinterpret this line.

Note the use of katakana カラ instead of kanji 殻 (perhaps the sign is written for children?). Google finds 277,000 phrase ghits for 玉子の殻, 225,000 for 卵殻, and 28,800 for 玉子のカラ.

Here's the English presented on the sign:

1. It is only combined sales

2. It will have it in two days on the day.

3. The pain becomes early if it puts it in the plastic bag etc.

4. Garbage of an egg to a trash box. Let's make Hakone beautiful.

The Chinese is likewise nearly unintelligible; rendered into English, it goes something like this:

1. Using one's number, can't be sold off.

2. Keepable for two days.

3. When packed into eth(yl)ene pocket pain will become early.

4. Arriving at the eggshell garbage box. Let's clean Hakone!

The Korean is a bit better, but still awkward and fraught with problems (even the last line, which is the only one that is really grammatical):

1. Within a round number of one, can't be sold.

2. Preservation is for two days time.

3. If [they] are put in a plastic bag, pain becomes quick–…..

4. Egg shells to the garbage can. Let's make Hakone clean.

One of the strangest parts of the Korean translation is that the third instruction is incomplete. Most unfortunately, moreover, the fourth instruction uses an inappropriate word for "egg." In Korean there are different words for “eggs” and the translation for #4 does not choose the correct one, kyeran ("chicken egg") but instead uses the generic word for "egg," al, which includes even the eggs of reptiles. The ellipsis of the verb in the first sentence of #4 is acceptable in Korean, as it is in Japanese, though it is ungrammatical in English to omit the verb in this sentence, as is done in the English translation on the sign.

For those who are interested, it may be useful to provide some background information about the life-extending eggs of Hakone. Eggs are boiled in the sulfurous springs at Ōwaku-dani, a process which makes their shells turn black. Here is a scene showing the vats where the eggs are boiled:

Local legend has it that one of these eggs can extend your life by seven years, and they're sold in various sets, the most popular apparently being sets of five.

Here are the benefits one allegedly reaps from eating these eggs:

There is a picture and a tiny bit of text in English about these eggs under the "Eat" section of the Wiki Travel page for Hakone.

From talking to friends who have actually been to the Hakone hot springs area and eaten these special eggs, they are absolutely delicious, some of the best boiled eggs my friends have ever had.

Incidentally, while you're in the area where they make these eggs, you've got to be careful not to breathe, since the sulfurous gases may be FATAL:

The translations on this sign are superior to those on the window of the shop that sells the eggs, but still unintentionally humorous for their overly earnest warnings.

[With a tip of the hat to Joel Martinsen, and many thanks to Bob Ramsey, Michael Carr, Kathryn Hemmann, Miki Morita, Daniel Sou, Nathan Hopson, Min-Hyung Yoo, and Minkyung Ji.]

Edith Maxwell said,

August 5, 2010 @ 1:43 pm

Wonderful (mis)translations, indeed. I believe that's hiragana, though, not katakana, and there is certainly kanji mixed in, as is conventional in written Japanese for nouns and verb roots (although it's been 30+years since I studied it).

Leonardo Boiko said,

August 5, 2010 @ 1:55 pm

Edith: he’s talking specifically about the word kara “shell”, which is commonly written as kanji (殻) and in this sign is written as katakana (カラ) instead. Since 殻 is a grade 8 jōyō kanji, it might indeed be written that way in order to be readable for children (I guess).

In defense of the life-extending claims, the English version does take the care of saying longevity might or may be postponed…

Karen said,

August 5, 2010 @ 2:06 pm

But surely you don't want longevity to be postponed! It's DEATH you want postponed. Longevity should be prolonged…

Children use hiragana instead of katakana before they acquire all the kanji. The use of katakana is for emphasis or foreign words… Maybe they're shouting the word "shells", just as perhaps the Korean translator wanted to encourage you to toss all your shells, not just these…

groki said,

August 5, 2010 @ 2:12 pm

in the English of the benefits picture, I too was first struck by the thought of postponed longevity: you'll live longer, but not for a while yet. some strange version of reincarnation, maybe? :)

then I noticed the "might … for" and "may … during" distinction was only in the English. I'm illiterate in all three other scripts, but the (I assume) Chinese and Korean seem, except for the numbers, to be exactly the same in both sentences. and the Japanese seems to have only a single phrase for the (again, I assume) longevity portion of the statement.

why the difference for English, I wonder?

Leonardo Boiko said,

August 5, 2010 @ 2:21 pm

@Karen: But children who can read the other kanji in the sign would have long learned katakana.

Another possibility: perhaps the sign author simply forgot the character for shell, and wrote it as katakana just to separate the word from the surrounding particles (recall that Japanese usually doesn’t use spaces; compare: 1) 玉子のからはゴミ箱へ。 2) 玉子のカラはゴミ箱へ。)

Leonardo Boiko said,

August 5, 2010 @ 2:26 pm

> The use of katakana is for emphasis or foreign words

Usually, yes, but it is also employed for general emphasis, similar to our italics. And today’s wikipedia says (with examples):

> It is very common to write words with difficult-to-read kanji in katakana.

Chris D said,

August 5, 2010 @ 2:27 pm

The Japanese version has an interesting way of indicating the modality here, by using the particle sequence とか "to ka" after the set of claims. which might be translated as "and such", but in this instance feels like a kind of hearsay evidential – so a good translation might say something like "It is said that if you eat one of these eggs…"

groki said,

August 5, 2010 @ 2:32 pm

another distinction, this time only for the (I assume) Korean: that's the only part where the 2-egg claim is first.

is that just happenstance, or is there some more language-specific order-of-concepts thing going on?

TLO said,

August 5, 2010 @ 2:37 pm

I did a Google search for each combination of 玉子/卵/たまご/タマゴ and 殻/から/カラ, and here are the ranked results:

たまごのから 368,000

卵のカラ 364,000

タマゴの殻 294,000

玉子のから 293,000

玉子の殻 277,000

卵のから 274,000

卵の殻 161,000

タマゴのから 98,300

たまごのカラ 91,500

タマゴのカラ 70,400

玉子のカラ 27,000

たまごの殻 18,500

It’s interesting that each spelling of each word occurs in the top four. It’s also interesting that though 玉子のカラ is second-to-last, 卵のカラ is second overall.

Incidentally, I visited Ōwakudani just last week, but I didn’t try the eggs, mostly due to rule 1. I was alone and didn’t feel like either eating six eggs or carrying leftovers around with me. I guess I might have missed out on an extra forty-two years of life!

Chris D said,

August 5, 2010 @ 2:54 pm

On the topic of speculations as to why カラ "shell" is written in katakana:

The word aka, which means something like "grime", and is typically used to refer to the dirt and grime that one removes from the skin (in, say, a shower outside the Hakone hotsprings) can be written with the Chinese character 垢. But it is often written in katakana, as アカ. Similarly, the word fuke, which means "dandruff", appears in the dictionary written in hiragana, as ふけ. But a quick google search for "頭のフケ" (head dandruff) returns plenty of results in which fuke is written in katakana.

My impression from reading the backs of personal hygiene products is that words for these sort of things – roughly, parts of your body that you would like to remove in some way – are very often written in katakana (while everything else that you might expect to be written in kanji or hiragana is so written). In addition to the two examples above, I just found the following on the back of a bottle of Japanese face wash:

ニキビ予防にも効果的

nikibi yobou ni mo koukateki

"also effective in preventing pimples"

The word for "pimple" is nikibi, which here is written in katakana ニキビ despite the fact that it has an associated kanji form 面皰, and in dictionaries is written either in kanji or in katakana.

On the basis of the above, I humbly submit the following generalization: words for things that one wishes to remove or otherwise dispose of are often written in katakana, especially in contexts where the undesirability of these things is being advertised. Thus, the back of soaps and shampoo bottles will describe the things they remove using katakana, and in the signage in this post the shells of the eggs are so written, as they are at this point a kind of waste to be disposed of.

Notice, incidentally, that the word for garbage, gomi, is itself written using katakana, both in the signage here and more generally.

Jongseong Park said,

August 5, 2010 @ 2:56 pm

The word 알 al used for 'egg' in Korean means not only generic eggs, but can refer to any number of small round objects like grapes, grains of cereals, nuts, beads, even lenses. So you really do need to specifiy 'chicken egg' and say 계란 gyeran or 달걀 dalgyal.

I love how they translate the life-extending benefits into Korean with the construction -ㄹ지도 모릅니다 -ljido moreumnida, meaning, very roughly, 'you never know'. This construction sounds more natural to warn of the possibility of something undesirable happening, so the effect is: 'If you eat one egg, your live span is liable to increase by seven years, so don't say we didn't warn you!'

Chris D said,

August 5, 2010 @ 2:57 pm

Doh – in the post above, I meant to say that nikibi "pimples" appears in dictionaries written with either kanji or *hiragana*.

Tenderfoot said,

August 5, 2010 @ 3:03 pm

3. The pain becomes early if it puts it in the plastic bag etc.

Isn't that what Buffalo Bill said to Catherine in "The Silence of the Lambs"?

Karen said,

August 5, 2010 @ 3:23 pm

@ Leonard: I don't dispute that they could read katakana if they can read the kanji. My only information, which is probably incomplete, is that stuff for kids is written in hiragana, not katakana, whether they can read it or not – at least that's what my learner's book tells me. For instance, furigana (the small-print words written above or beside kanji to assist children in learning them) is in hiragana, not katakana.

That's why I lean towards an "it's for emphasis" rather than "it's for children" theory, especially since you'd think "shell" wouldn't be the most obscure word on that sign.

J Greely said,

August 5, 2010 @ 5:48 pm

Our tour guide at Ōwaku-dani added a third clause, "if you eat three eggs, you will live until you die".

-j

sonsofloki said,

August 5, 2010 @ 6:28 pm

I must have eaten a dozen of those eggs over the years, so I can't help but wonder how long I'll be living for. (They really are delicious, sulphur-y and smoky.)

As for カラ in katakana, I'd guess it's for emphasis and readability (and から would be a little confusing in hiragana). With IME these days, there's no reason a literate adult would forget the kanji.

Tim Martin said,

August 5, 2010 @ 6:48 pm

I'm going to agree with the people who are saying, there's really nothing strange about a word like 'kara' being written in katakana. It's a very common occurence. Perhaps a generalized explanation such as Chris D's is correct, but I wouldn't agree that this sign was meant to be kid-friendly, or that the writer just forgot the kanji.

áine ní dhonnchadha said,

August 5, 2010 @ 6:58 pm

This is a perfect example of why playing Philip K. Dick's translation game is the most fun. I put the Japanese into translate.google and got:

1. Mesen selling roses and forum.

2. Su has been a two-day shelf life.

3. And will soon be put in a plastic bag and killers.

4. The egg color to the Trash.

Shima Translations Play Audio Hakone clean.

(The Philip K. Dick translation game is from a few of his books, wherein you use a computer to translate book titles and then back again and the opponent has to guess the original title.)

john riemann soong said,

August 5, 2010 @ 9:02 pm

The issue is you need a script to correct the gibberish to something grammatical, so you can run it through over and over.

Are there any algorithms that try to combine universal grammar methods with statistical engines? I wonder if it's possible to write a program that is hard coded with a few very fundamental basic rules for interpreting grammar and word order, then learns statistically.

Take for example a word that is frequently interpreted as "pain" (noun) rather than "spoil". So the second interpretation has maybe a normalized score of 17% say, versus "pain"'s score of 54%. But shouldn't the program be able to throw out the agrammatical one in favour of the grammatical one?

(I know nothing about statistical translation engines, though…)

Tim Martin said,

August 5, 2010 @ 9:11 pm

"But shouldn't the program be able to throw out the agrammatical one in favour of the grammatical one?"

Well, in this case they were both grammatical – 'itami' is a noun either way. What the Japanese says is "the pain/spoiling will become faster." It's only when you give it a natural English translation that you make 'spoil' a verb.

Janne said,

August 5, 2010 @ 10:03 pm

I agree that "kara" is probably just a stylistic emphasis, like using italics or bold. As far as I know there's no hard and fast rules on when to use kanji, hiragana or katakana spelling, and signs and advertisements especially tend to be pretty creative about this.

But depending on the word, a change of script may have specific meaning. One example is "hito" (man, human). When written as "人" it just means person. But in science-related writing, "ヒト" in katakana specifically denotes "human" as a species (rather than person or people generally). It's possible "kara" has some similar specific meaning in katakana, but if so I haven't heard of it.

?! said,

August 6, 2010 @ 8:46 am

'Kara' in hiragana (can't type it on my phone sorry) is a VERY common compound/particle meaning 'from' or 'because', the latter as a suffix. It seems natural to avoid transcribing a character normally seen in kanji into hiragana when it might be confused with a common hiragana compound.

TLO said,

August 6, 2010 @ 9:38 am

@?!

I don't think there's really any danger of confusion, as the structure of the sentence makes it quite clear that 'kara' is a noun here.

I agree with Tim Martin: the fact that 'kara' is written in katakana doesn't necessarily mean anything in particular. I'd say it's akin to the choice of whether to use digits or spell out numbers. It can be done to make a point, or give some emphasis, or it can be done just because you feel like it.

Philip Spaelti said,

August 6, 2010 @ 12:39 pm

One interesting aspect of cases like カラ is that this word is a typical case of polysemy split that is forced on Japanese all the time. "Kara" etymologically means 'empty'. So the "kara" is just the empty egg, or grain hull, or bean pod etc. But the meaning empty is always written with the Kanji 空. In this case the semantic basis for the distinction is fairly clear, but in many cases this requires extensive drilling on the part of the poor Japanese kids.

Ironically in this case the Kanji 空 is also used for word "sora" 'sky' which from the Japanese point makes no particular sense. But presumably Chinese use the same word for both 'empty' and 'sky', but not for shells and pods.

Jeff DeMarco said,

August 6, 2010 @ 1:40 pm

You don't even want to know what "hakone" means in Guarani…

Janne said,

August 6, 2010 @ 7:28 pm

@Philip, the kanji for kara/shell is 殻, not 空. They only have the reading in common, nothing else.

J. Goard said,

August 7, 2010 @ 4:01 am

@Jongseong Park:

The word 알 al used for 'egg' in Korean means not only generic eggs, but can refer to any number of small round objects like grapes, grains of cereals, nuts, beads, even lenses.

Maybe it's also worth noting that 껍질 (kkeopjil) is not nearly as specific as English shell, but rather corresponds to a lot of English words: a fruit's peel/skin/rind, pig's skin/pork rinds, a rice grain's hull, a tree's bark… so it doesn't help clarify much. I find that Koreans learning English tend to blank at these kind of one-to-many translations of common words, so I pay them particular attention.

BTW, is there any difference for you between 껍데기 and 껍질? They seem to be used for all of the same things, but maybe with different frequencies? Is one better for an egg and another for a tree?

Jongseong Park said,

August 7, 2010 @ 9:07 am

@J. Goard,

Excellent point about the non-specificity of 껍질 kkeopjil. 알의 껍질 could potentially refer to any number of things.

As for 껍질 kkeopjil and 껍데기 kkeopdegi, I only had a native speaker's intuition about when to use either term in specific cases but had difficulty coming up with a general explanation. So I looked it up.

According to dictionary definitions, kkeopjil is used for a covering that is softer and doesn't separate easily from the inner substance, while kkeopdegi is harder in general and separates easily from the inner substance. So according to the usage guides found online, fruit peels and tree barks are kkeopjil, while sea shells and egg shells are kkeopdegi!

This means I've been using it wrong, since I often say kkeopjil for egg shells. But in general, my own usage agrees broadly with the definitions. I would always use kkeopjil for fruit peels and tree barks. I would not say I would never use it for sea shells, but I would prefer kkeopdegi.

For me, there is an ambiguity for egg shells because it feels like it's somewhere between fruit peels at one end of the spectrum and sea shells or walnut shells at the other. I'm not the only one who uses kkeopjil for egg shells; type in 계란껍 or 달걀껍 on Google, and they are completed automatically as 계란껍질 or 달걀껍질.

Kkeopdegi has a secondary meaning as 'that which is left when the inside is removed', as in the description 껍데기만 남은 kkeopdegi-man nameun, 'all that is left is the shell'. One would never use kkeopjil in this sense unless the thing that is left was a kkeopjil to begin with.

I've also found people peeving online about using kkeopdegi for pork rinds, when kkeopjil is the correct term per the dictionary definition. I don't talk about pork rinds that often so I don't have an existing preference.

J. Goard said,

August 8, 2010 @ 3:36 am

Wow, thanks… that's more fascinating than I expected!

Michael Rank said,

August 9, 2010 @ 5:27 pm

#

Jeff DeMarco said,

August 6, 2010 @ 1:40 pm

You don't even want to know what "hakone" means in Guarani…

Oh yes I do

If you eat twelve eggs said,

August 9, 2010 @ 9:04 pm

“One of the strangest parts of the Korean translation is that the third instruction is incomplete.”

It may not be an instruction, but I see a perfectly grammatical ending in the first picture.

Scott said,

August 10, 2010 @ 9:58 pm

The phrase I found most hilarious in the whole collection was "dedicate bronchus" in the sulfur spring sign. I wonder how exactly the translator moved from "delicate" to "dedicate"; I also find it odd that whatever software or dictionary they used recommended "bronchus" before "lungs".

dp said,

August 12, 2010 @ 10:20 am

Makes one wonder if the Rosetta Stone contained a similar mish-mash of language.