Dutch DE

« previous post | next post »

Following up on yesterday's post "The case of the disappearing determiners", Gosse Bouma sent me some data from the CGN ("Corpus Gesproken Nederlands"), about determiner use in spoken Dutch by people born between 1914 and 1987. According to the CGN website,

The Spoken Dutch Corpus project was aimed at the construction of a database of contemporary standard Dutch as spoken by adults in The Netherlands and Flanders. […] In version 1.0, the results are presented that have emerged from the project. The total number of words available here is nearly 9 million (800 hours of speech). Some 3.3 million words were collected in Flanders, well over 5.6 million in The Netherlands.

It's not clear to me exactly when the recordings were made, but the project ran from 1998 to 2004.

Gosse sent data focused on the word de, which is the definite article for masculine and feminine ("common") nouns in Dutch, cognate with English the. (The definite article for neuter nouns, het, is less frequent and also can be used as a pronoun.)

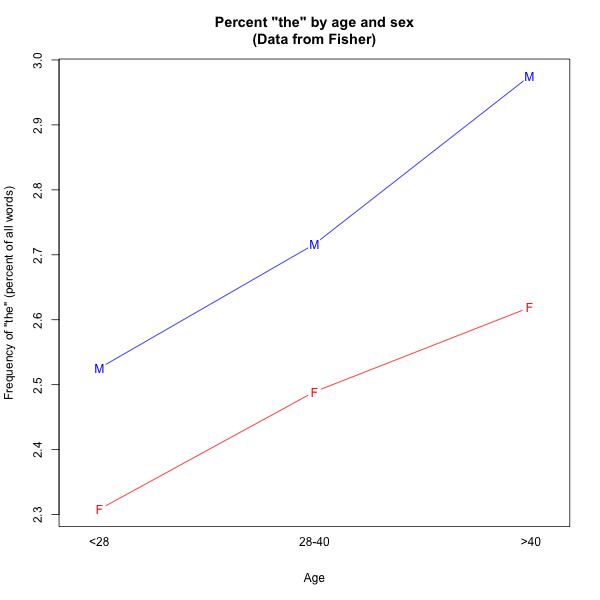

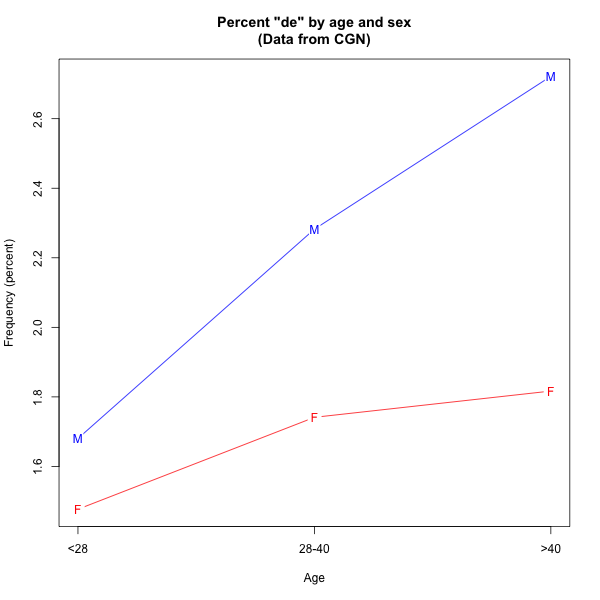

The results are similar to those that I reported earlier for English: Older people use the definite article more frequently than younger people (at least for people born in the 1950s onwards), and at every age, men use the definite article more than women.

Here are the English and Dutch results plotting in the same way. The English dataset was collected via telephone recording in 2003; the Dutch dataset was collected via face-to-face interviews between 1998 and 2004, so I've calculated ages from birth years relative to the year 2000:

| English (Results from Fisher) | Dutch (Results from CGN) |

|

|

As I observed, this pattern of age and sex effects is generally an indication of a language change in progress.

If we plot the Dutch data by decade of birth, we see a rise from birth decades 1910 to 1950, and then a steeper fall from the 1950s to the 1980s:

This is again similar to what we saw in the Google Books ngram corpus for German:

Data from the KB Historische Kranten corpus (of Dutch newspaper data) shows a generally similar pattern of rise and fall over the course of the 20th century, if we add the counts for DE, DEN, DER, DES (which were collapsed into "de" by the Spelling Reform of 1934 — apparently not really carried out in newpapers until after WWII):

(That dataset runs through 1995 — I've left out the point for the year 1995, since it seems anomalous.)

The sex effects in the CGN dataset are quite large. Males in this large collection use DE much more frequently than females do. The male/female ratio is about 1.48/1 across the whole collection (2.721% vs. 1.841%), though the ratio is smaller for younger people (1.64/1.33 = 1.23/1 for people born in the 1980s, VS. 3.07/1.81 = 1.70/1 for people born in the 1950s).

The newspaper percentages seem more female-like in the early years of the 20th century, rising to a more male-like level in the middle of the century, and then falling again. Could this be due to changes in the formality of newspaper writing in general, or the mix of sources in the KB Kranten corpus in particular?

Breaking the CGN female and male DE-usage numbers down by birth decade:

| Birth Decade | #Male | #Female | M DE% | F DE% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 1 | 5 | 3.77% | 1.98% |

| 1920 | 22 | 22 | 2.22% | 1.65% |

| 1930 | 60 | 43 | 2.84% | 1.79% |

| 1940 | 175 | 134 | 2.40% | 1.86% |

| 1950 | 177 | 127 | 3.07% | 1.81% |

| 1960 | 181 | 133 | 2.35% | 1.80% |

| 1970 | 216 | 278 | 1.76% | 1.56% |

| 1980 | 60 | 101 | 1.64% | 1.33% |

Leaving out the people born in the 1910s (because their numbers are so low), we get this plot:

And here's the same plot for HET (collapsing across the transcriptions "het" and "@t" (the reduced form), and limiting the count to those words given the pos-tag of determiner:

There are many details that don't quite match across the various languages and datasets that we've looked at. But there seems to be strong evidence for a general pattern of substantial decline in the frequency of definite articles in several European languages, at least over the last portion of the 20th century.

This raises the interesting questions of how and why. Yesterday's post (and the valuable comments on it) suggest many ideas to test — I'll look forward to seeing how it all comes out.

Allison said,

January 4, 2016 @ 4:22 pm

It strikes me that there's a potential confounding effect in Dutch that you don't have in English: the seemingly omnipresent use of the diminutive in Dutch. Whenever a noun is turned into a diminutive it becomes a "het" word, even if it was a "de" word before. I don't know if women or younger people use diminutives more than men or older people, but it seems possible – perhaps someone with more linguistics cred than I can find out!

[(myl) Interesting idea, but it probably doesn't work as the explanation of the change in the frequency of DE. In the newspaper corpus, the relative frequency of HET rises and falls almost exactly in step with the relative frequency of DE — especially with DEN+DER+DES added to DE — and the post-1950 fall in particular is quite parallel for the two words:

Note that those are proportional frequencies, i.e. the frequency vectors divided by their means — the actual frequency of HET in this corpus is only about half that of DE.

Corrected for the mid-century spelling reform(s), the DE/HET ratio falls gently from about 2.7 in the 1920s to 2.5 in the 1990s. This might be due to an increase in diminutives in the written language, as you suggest — but it's not nearly enough to explain the observed drop in the frequency of DE:

(The pre-1920 discontinuity must be the result of some earlier spelling reform, I guess…)

I'll ask Gosse for data on the CGN situation.]

R. Baars said,

January 5, 2016 @ 2:01 am

It is extremely risky to conclude on such old and sparse data.

[(myl) This comment is quite puzzling.

"Old"? We're interested in history, so some of the data needs to be old.

"Sparse"? The newspaper corpus covers 28,355,900,295 words of text from 1900 to 1994, and the CGN involves nearly 9 million words of transcript from 1,735 speakers.

More data is always good, but this is plenty. And it would be nice to have data about what has happened since 2000, but that's not central to the discussion.

So have I misunderstood your point, or missed an ironic inversion? Or are you just trolling?]

Willem J. de Reuse said,

January 5, 2016 @ 1:24 pm

Very interesting data. My question is the following: is there a concomitant rise of the frequency of the indefinite sg. een/indefinite pl. zero? (i.e. matching English a(n)/zero) If so, I think the explanation could have to do with globalization. In earlier times people talked more about things they could assume the hearer/reader to be familiar with, in a village context for example. Now, with communication intended for the whole world, it would make sense to use indefinites more often, and definites less often. Just a thought…

[(myl) With respect to EEN, the answer is "no":

With respect to zero, it's hard to count it in a 1-gram frequency list :-(… ]

christoll said,

January 6, 2016 @ 6:30 pm

Mark, doesn't your graph there for EEN actually suggest that the answer is at least partly "yes"? It looks like an almost perfect left-to-right inversion of your earlier graphs for DE etc. for the same source. Sure, the graphs both have troughs and peaks in the same decades, presumably reflecting the changing frequency of noun use in general, but the lowest area of the EEN curve is at the far left, whereas the lowest area of the DE curve is at the far right, and the high areas in the middle decades show a similar inversion. This is pretty much exactly the amount of variation you would expect if EEN was sometimes replacing DE, isn't it?

[(myl) But if we compare DE+HET+EEN to DE+HET, adding EEN doesn't really level things out, as we would expect it to do if DE and HET were being replaced to a significant extent by EEN:

]

Alen said,

January 7, 2016 @ 8:45 am

In line with Allison's comment above, it should be noted that all plural nouns in Dutch take 'de' even if they take 'het' in the singular. Can't see it making a lot of difference to the interpretation of the data, though, as the 'de+Het graph above indicates.