Clinical applications of speech technology

« previous post | next post »

I'm spending this week at IEEE ICASSP 2010 in Dallas. ICASSP stands for "International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing", and it's one of those enormous meetings with a couple of thousand attendees. This one has more than 120 sessions, with presentations on topics ranging from "Pareto-Optimal Solutions of Nash Bargaining Resource Allocation Games with Spectral Mask and Total Power Constraints" to "Matching Canvas Weave Patterns from Processing X-Ray Images of Master Paintings".

The large number of parallel sessions make it impossible for any one person to attend more than a tiny fraction of the interesting papers, but luckily, ICASSP is one of the (many) conferences that now require would-be presenters to submit a paper (in this case, 4 pages), not just a short abstract. All accepted papers are then published on a CD given to attendees.

This practice is an enormous step up, in all respects, from the old-fashioned idea of submitting an abstract of a couple of hundred words. It makes it possible for the program committee to referee submissions on a rational basis. What is even more important, it means that the conference proceedings become a crucial mode of technical communication. In many subfields, such conference papers (typically made available for free in reprint archives or on authors' home pages) now play a more important role than journal publication does.

[I wish that the LSA would totter into the 1980s and join this trend…]

I'll illustrate the value of such conference papers with one example that I stumbled across yesterday. If I have time, I'll blog about some others later on.

The specific ICASSP paper that I'm talking about is Athanasios Tsanas et al., "Enhanced Classical Dysphonia Measures and Sparse Regression for Telemonitoring of Parkinson's Disease Progression". Their abstract:

Dysphonia measures are signal processing algorithms that offer an objective method for characterizing voice disorders from recorded speech signals. In this paper, we study disordered voices of people with Parkinson’s disease (PD). Here, we demonstrate that a simple logarithmic transformation of these dysphonia measures can significantly enhance their potential for identifying subtle changes in PD symptoms. The superiority of the log-transformed measures is reflected in feature selection results using Bayesian Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) linear regression. We demonstrate the effectiveness of this enhancement in the emerging application of automated characterization of PD symptom progression from voice signals, rated on the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), the gold standard clinical metric for PD. Using least squares regression, we show that UPDRS can be accurately predicted to within six points of the clinicians’ observations.

That "within six points" should be interpreted with respect to the overall range of the metric (which is 0-176 for the total UPDRS, and 0-108 for the motor portion of the scale), and also with respect to the distribution of values among the 42 subjects in this study. This last distribution is not clearly specified in the paper, but we do learn that

The 42 subjects (28 males) had an age range (mean ± std) 64.4 ± 9.24 years, average motor-UPDRS 20.84 ± 8.82 points and average total UPDRS 28.44 ± 11.52 points.

The dysphonia measures used were based on subjects' attempts to produce extended steady-state vowel sounds, and included various variations on standard phonetic measurements of jitter (local perturbation in pitch), shimmer (local perturbations of amplitude) , and harmonics-to-noise ratio (breathiness).

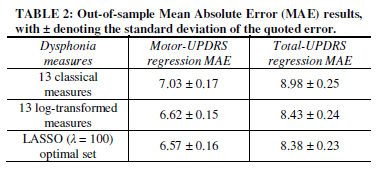

As this table suggests, the core result was simply that these dysphonia measures predicted the clinician's numerical judgments within about seven to nine points.

The paper's technical innovations (log transform of the jitter and shimmer measures, and subsequent feature selection) improved this baseline performance by about 7%. (Let me note in passing that the authors use ten-fold cross-validation and other appropriate techniques in making these estimates. This is worth noting, since researchers in disciplines like psychology and sociology sometimes report regression residuals or similar results without doing this, thus in effect testing on their training material and offering an inflated idea of the quality of their predictions.)

I don't know enough about the distribution of UPDRS values in the subject pool, or the typical repeatability of clinicians' UPDRS assignments to individual patients, to evaluate this description of the residuals. And I don't know enough about the clinical management of Parkinson's patients to evaluate how useful this level of prediction would be as a monitoring tool, by itself or in combination with other inputs. But to my eye — that of someone who understands the speech science and the basic statistical issues reasonably well, and has a superficial understanding of the medical issues — this looks promising.

More generally, I'm convinced that it's possible to quantify many speech- and language-based diagnostic indicators,with sensitivity, specificity, and repeatability that compare favorably with many of the physiological tests in common use today. And these linguistic tests are totally non-invasive, require no apparatus other than a microphone and a computer, and in many cases can be administered remotely.

Considering the possible benefits, there's remarkably little research of this kind, overall, and so I was happy to find a specific example of such high quality.

(Note that I could get this far in learning about this conference presentation because it exists as a coherent document, published in the conference proceedings and also on the authors' web site. If ICASSP were run like the LSA meeting, with a 200-word abstract being the only concrete record of a presentation, I wouldn't be writing this. And even if the live presentation (in this case a poster) had caught my eye, I might never have remembered to follow up on it.)

[Update 3/21/2010: — In reference to this post, Athanasios Tsanas writes:

Your concerns there are right: the distribution of the motor-UPDRS and total-UPDRS scores are not mentioned (roughly these are Gaussian shape like, with a peak almost in the middle of the range of values). Clinically, I got the impression that medics are satisfied with UPDRS estimates within about 5 points of their evaluations – which is the inter-rater variability, i.e. the UPDRS difference that might occur in the evaluation of patients between two trained clinicians. In fact, my latest results suggest we can do considerably better than that, further endorsing the argument of using speech signals to track average Parkinson's disease symptom severity. These new results are derived by using some novel nonlinear speech signal processing algorithms which complement the already established measures, and we are submitting a paper describing all that soon.

]

Jens said,

March 18, 2010 @ 12:33 pm

As a computer scientist I am somewhat amazed that having to submit a full paper is worthy of mention. I honestly don't know of a reputable conference that does not have published peer-reviewed proceedings and acceptance is always based on the actual article (usually 8-10 pages).

[(myl) Yes, that is one of the worlds that I live in. Conference papers are 4-12 pages, depending on the case. Refereeing is done on the basis of a draft; there is usually an opportunity to submit a revised version if you want to. Things have been this way since the 1970s at least, and probably before that.

Then there are the disciplines where everything is based on a short abstract. In the case of the LSA annual meeting, refereeing is done on the basis of a one-page abstract, and the only thing that is printed (yes, still printed) in the meeting handbook is an even shorter 200-word abstract. (The widespread belief that the abstract must be written with a quill pen is in fact false; this hasn't been true since 1997. Just kidding.)

For years, the suggestion to move to (say) an 8-page paper format for the LSA annual meeting was taken roughly as seriously as the proposition that all presenters should be required to provide simultaneous translation in Tahitian. Now at least the suggestion is taken seriously enough that people give a long, seriously-meant list of reasons why it can't possible work.]

There really seems to be a huge gap between different disciplines. In CS it can often be more difficult to have a paper accepted at a top conference than in a journal, yet in many countries official guidelines dictate that only journals are counted when applying for a university position.

[(myl) Yes, the acceptance rate for the ACL's formal journal has at times been three times higher than the acceptance rate for its annual meeting. (Though I think that this relationship has recently been rectified.)]

Henning Makholm said,

March 18, 2010 @ 1:46 pm

What Jens said. In my experience, also as a computer scientist, the paper is the main thing, to which the live presentation is distinctly secondary. The talk is generally considered an opportunity to convince a semi-captive audience that they should go read the paper.

In fact, even attending a conference is mostly just a way to celebrate getting a paper into the proceedings (as it is usually difficult to get one's participation funded without having a paper accepted, at least for junior researchers without a budget of their own).

peter said,

March 18, 2010 @ 1:51 pm

Jens — Sadly, the same goes for promotions for academic computer scientists. Internal university promotions committees are usually dominated by other scientists who value papers in journals far more highly than papers at refereed conferences, even after the situation in CS is explained to them. Acceptance rates at top CS conferences usually do not exceed 25%, while acceptance rates for journals in CS are often 50% or higher. Moreover, it is increasingly rare for researchers to read the journal publications of other academic computer scientists – we read their conference papers, workshop papers, and preprints to be found on their web-pages.

[(myl) There are many subdisciplines in CS, mathematics, physics, etc., where older researchers may be hard pressed to remember when they last read a journal paper, and (I presume) many younger researchers have never done so.]

mgh said,

March 18, 2010 @ 3:58 pm

What is the difference between publishing results through a peer-reviewed highly selective conference program committee, and publishing results through a peer-reviewed highly selective scientific journal?

[(myl) In principle, none. In practice, there are many differences. One is timeliness — journal papers are often (e.g. in Language) printed two or three years after submission. For conferences and workshops, the lag is significantly shorter. For example, in the case of the current ICASSP meeting, the submission deadline as 9/15/2009; the deadline for submission of revisions to accepted papers was 1/5/2010; the meeting began 3/14/2010. So you're seeing work within 3-6 months of when it was done. A second difference is process complexity: conference and workshop papers are generally either accepted or rejected (though in either case with an explanation, often a fairly elaborate one), whereas journal papers often must go through a series of revise-and-resubmit cycles, which may or may not make them better, but certainly make them later.]

Coming from a field where the pleasure of going to meetings is to hear about stories in progress, where many talks contain data that was probably not even obtained yet when the abstract deadline passed, the attraction of a meeting where the presentations are all – by definition! – from published work is not immediately obvious.

[(myl) Of course you'll hear those stories any place where researchers gather. But unless the meeting (and the field) is small enough for you to hear all the stories (and the fields that I'm in mostly are not), then it's better at least to be able to read about the work done 3-6 months earlier.

And even the current stories have the problem that uptake and memory are not always reliable. Some of the best research I've ever heard described has turned out to have been taken place somewhere between my perception and my recall of the presentation.]

Jan van Santen said,

March 18, 2010 @ 5:07 pm

Mark makes good points about the feasibility and value of speech- and language-based diagnostic indicators. In fact, we have several projects of this general nature in our group: http://www.cslu.ogi.edu/projects/researchprojects.html#BIOMEDICAL_RESEARCH_PROJECTS

Simon Musgrave said,

March 18, 2010 @ 6:45 pm

We in Australia are in the middle of the latest government exercise in quantifying research activity – in order to establish quality, naturally!

In checking my submitted data the other day, I was pleasantly surprised to see that publication in COLING proceedings was rated in the same way that journal publication was rated (I hasten to add that I was only fourth author on that piece of work) – however, that was the only conference paper publication that was so rated.

Less pleasant was finding out that the International Journal of the Sociology of Language had been rated by sociologists, and ranked in the lowest tier of journals.

marie-lucie said,

March 18, 2010 @ 6:59 pm

Not all conferences publish proceedings (in whatever form) and there is a vast difference between disciplines. In linguistics per se, it is true that you submit a long and then a short abstract, but the latter is not all the audience will see: most presenters (if they are not just using PowerPoint) prepare a handout which is an outline of the paper with the main points and (crucially) the actual examples. You can come back from a linguistics conference with quite a stack of such handouts, even if you only take home the ones that you find relevant for yourself (and if you are unable to attend a particular paper or session, if you are lucky there will be leftover handouts you can pick up after the session). For linguistics conference proceedings which resemble journal articles, a 4-page or even an 8-page paper (as opposed to just a handout) would usually be much too short.

[(myl) Except that most people don't bring nearly enough handouts, so that even if you get to go to the talk, you may or may not get one; and if you miss the talk (say because there was another talk in a parallel session that you also wanted to hear, or because you yourself gave at talk in a parallel session) you're completely out of luck. Nor can those who don't make it to the conference learn anything about what went on there.

In any event, handouts are of highly variable quality, and are not refereed at all, and can be cited only in extremis, and so so. In contrast, a paper in the proceedings of a conference is an archived publication.

These days, to "publish" the conference proceedings requires only to put the papers up on a web site. Many (most?) universities these days have digital archive services who will be happy to help with this. So any imagined difficulty or expense of "publication" vanishes.

And in the context of networked digital publication, page restrictions matter only because of referees time budgets.]

Clarissa at Talk to the Clouds said,

March 18, 2010 @ 9:25 pm

Teaching-related (particularly TESOL affiliate) conferences are lagging way behind in terms of making materials available to the participants, either formally or informally. You would think, with all of our talk about learning communities and whatnot, we would know better.

marie-lucie said,

March 18, 2010 @ 9:34 pm

myl, thank you for your reply. I am well aware of the problems of not being able to attend conferences, or interesting papers given just at the time one is presenting. It is also true that it is very difficult to evaluate the number of handouts one should bring (or print on the spot), and this must also vary with the obscureness or popularity of one's own specialty. Handouts are indeed of variable quality, but so are papers in proceedings, especially if they are pre-prints. Perhaps your point is that in the digital age, it is possible for anyone to read conference papers, and therefore to decide whether or not a paper meets the required standard, but committees do not always include people knowledgeable enough in the specialty that they could evaluate a paper posted online rather than rely on the opinion of a refereed journal. A linguist in a small department, or the lone linguist in a department of something else, can rarely rely on their departmental colleagues to have enough background in linguistics, let alone in the precise specialty, to evaluate a paper that has not appeared in a refereed journal of some repute.

[(myl) No, my fundamental point is that digital conference proceedings, publishing some form of a full paper rather than an abstract, are a Good Thing for scholarly communications.]

Chris said,

March 18, 2010 @ 10:13 pm

I can only add a second hand experience to this thread, but I recall quite specifically a friend of mine at the recent LSA in Baltimore actually complaining about the opposite. Namely, that it was unreasonable to ask her to produce an 8 page submission just to be considered for a conference for which she had at best a 50/50 chance of being accepted. The pot odds didn't make sense (okay, that's my wording as a poker player, but you get the point).

[(myl) Why would she come to that conclusion with respect to a conference submission, but to a different conclusion with respect to a journal submission? What I learn from listening to many discussions of such things is that academics are one of the most culturally conservative groups ever documented, and just as inventive in post hoc rationalization of their habits as anyone else is.]

Note: her complaint was aired at the LSA, but it was directed at a different conference.

On a personal note, I'm in the odd position of being in, roughly, the Dallas area, but having plans to spend my three day weekend at the SXSW in Austin. Hmmmm, would crashing the IEEE ICASSP 2010 be worth the side trip? Any weird cognitive-ee, functionalist-ee, trippy linguistics going on?

[(myl) You can check out tomorrow's program here. You might enjoy the Dialog Systems & Language Modeling II session, or the Music Signal Processing session, or … Me, I'm shipping out on a 6:25 a.m. flight from DFW, heading to another meeting in Boston this weekend.]

peter said,

March 19, 2010 @ 3:15 am

myl: "And in the context of networked digital publication, page restrictions matter only because of referees time budgets."

Page limits also force authors to attend to what they most wish to communicate and how best to do so. Thus, form (page limits) has an impact on content. As Mark Twain observed, writing short documents is harder than and usually takes more time than writing long ones.

Chris said,

March 19, 2010 @ 10:16 am

@myl, I'm not sure what her response would be, but my gut tells me that a published paper is more prestigious than a conference presentation in most cases, and hence more worth the effort. I assume you've been on hiring committees, does that jive/jibe with your experience when judging CVs?

…and just how many conferences do you attend! Dear gawd man, take a vacation.

Cornelius Puschmann said,

March 19, 2010 @ 10:54 am

Mark,

not sure if you've heard, but the LSA has recently introduced submitting extended abstracts (4 pages) that summarize the content of talks post-conference. For now this is optional and it's likely that relatively few presenters will participate initially (extabs for 2010 will be published a few weeks from now), but we expect participation to increase a lot for the 2011 meeting. And from my viewpoint we'll move quite a bit beyond the 1980s by publishing those extended abstracts on eLanguage. Nothing wrong with CD-ROMs (great coasters), but who has a drive for playing them these days.

[(myl) I do know about this experiment, and will be pleasantly surprised if very many people take advantage of the opportunity.]

Julian Bradfield said,

March 19, 2010 @ 3:46 pm

I'm also a computer scientist, moonlighting in phonology, and one of

the great joys of my moonlighting is being able to go to conferences

where people are talking about things they think are fun and

interesting right now, instead of doing advertisements for papers

describing stuff done a year or more ago.

Personally, I also find it helpful to be able to do enough to justify

a one or two page abstract, and then do the rest if it's accepted.

(Obviously this only works because I'm a theorist.)

In my home discipline, you have to do all the work before finding out

that people aren't interested enough in it to accept it! Any

conference I might go to in CS has a 25% or so acceptance rate, so

even quite good work can be not quite interesting enough – which also

makes programme committee work hard. (Typically three or four people referee

each paper, and then there's a two-week electronic PC meeting, or just

occasionally a two-day physical meeting.)

I also disagree with your "fundamental point" that publishing full papers

is necessarily a good thing in conferences. Writing a good paper takes

a long time, even after all the work's been done. So do it in its own

time, and publish in a journal. If you want a record, put the slides

on a web page.

The irony is that there are quite a lot of people in my field of CS

who believe that we should revert to the unrefereed conferences that

don't count for anything on your CV, promotion, etc.! We look

admiringly at the pure mathematicians, where only journals count, and

conferences really are for presenting new stuff. (Or so we believe.)